Interview: Blackberry Smoke’s Charlie Starr on tone, bluegrass and why we should all listen to the Rolling Stones

Starr unpacks the gear, songs and inspirations behind the Atlanta, Georgia rocker's stellar new album You Hear Georgia

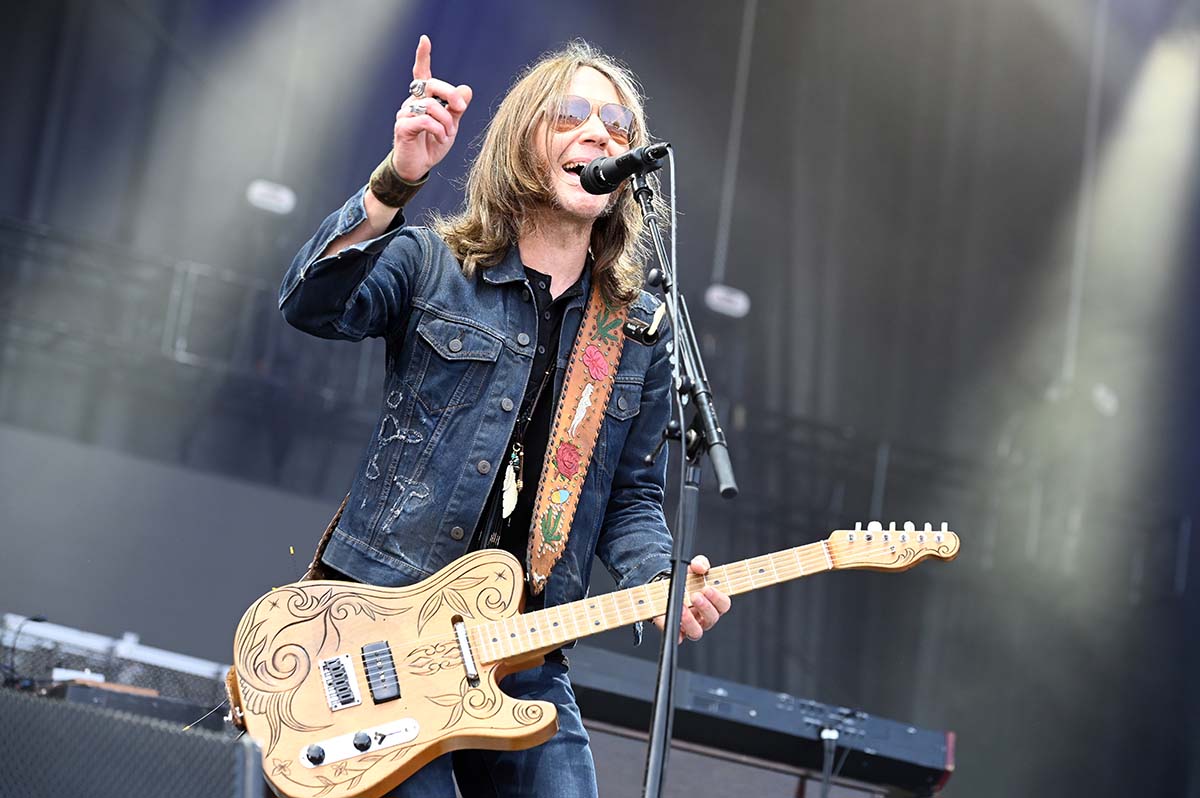

There is something reassuring about seeing Charlie Starr’s face pop up over a scratchy Zoom connection. It’s like a scene from a bygone era. Sure, the technology brokering the conversation is 21st century, but here is the Blackberry Smoke frontman and guitarist checking in from a tour bus.

You might remember them. They were used in what feels like a dim and distant past to ferry musicians to and from shows. Here’s hoping they will be a common sight in 2021. We join Starr as he is en route to play a set at Historic Columbia Speedway, Cayce, South Carolina. Open air and socially distanced, of course, but that will do. It’s a start.

Spring’s arrival has brought with it a sense of renewal. Nature is healing and there are some songs that need playing. Three of which will be pulled from Blackberry Smoke’s seventh studio album, You Hear Georgia.

Recorded with Dave Cobb in Nashville, Tennessee, it offers a panoramic treatment of southern rock. That means there are all kinds of styles in the pot. There's old-school rock 'n' roll, blues, country. You don't have to dig too far into the sound to hear a bluegrass influence.

There are Saturday night bar jams, tracks such as Live It Down and All Over The Road that hang on a riff, a groove and smokin’ hot guitar tone. Starr’s prodigious slide guitar skills light up the loose-hipped rock of Hey Delilah and the easy tempo of country ballad Lonesome For A Livin’. Then you’ve got the likes of Warren Haynes popping up on All Rise Again.

On You Hear Georgia, Dave had an old OR-100, graphics-only Orange head. It was loud as fuck! It rattled every window in the place – and there’s not even any windows!

You Hear Georgia is music for better times, long summer nights and lazy weekend afternoons, and Starr being the connoisseur of electric guitar that he is, it has some of the most premium guitar tones we have heard on a record for some time. You know the kind. It's the sound you can only get from vintage gear, a great producer and a great room to record in.

Oh, heckfire, Charlie Starr, this record sounds expensive. “Yeah, it is!,“ he laughs.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

But seriously, Charlie, the record sounds incredible. A lot of credit for that has to go to Dave Cobb. Was he someone you had in mind from the day one?

“Yeah, we did. I had actually been talking to him for quite a while. He is an old Atlanta guy. For a few years our schedules didn’t really line up. Finally, early in 2020, we decided, ‘Let’s go in in March.’ And we all know what happened in March, so we pushed it back until almost June. We started right at the end of May, the beginning of June, and we tracked for five days, mixed for five days, and then it went to mastering.”

And that was it? Done. That’s fast

“That’s fast. Yeah.”

Sometimes restrictions on your time can be liberating. Did that help you?

“We didn’t really look at it like, ‘We have to get this done!’ Everybody was wondering what was happening. We didn’t foresee ourselves going to work any time soon so Dave and I say down and chose our favourite 10 or 11 songs, out of 18 or so, and basically said, ‘Hey, let’s get enough done as we can, and if we don’t finish, we’ll come back.’”

The guitar tone on this record is magnificent. What did you use?

”Oh man! I used a couple late ‘50s Les Paul Juniors, a ’58 Les Paul Custom, a mid-‘60s [ES-] 330, a couple of old Martins – a 1950 D28 and a 1960 00-21. A couple of different Esquires, a ’65 and a ’62. Gosh! Dave has got tons of guitars, too, so there were a lot.”

Dave Cobb said, ‘You guys don’t have to bring anything. I have two or three of everything!’ But we both know that I didn’t listen to that advice, so we took tons and tons and tons of shit

The guitars tend to come easy. They find you. The amplifiers you've got to hunt down.

“You do, and again, on the way in Dave Cobb said, ‘You guys don’t have to bring anything. I have two or three of everything!’ But we both know that I didn’t listen to that advice, so we took tons and tons and tons of shit. [Laughs]“

Like what?

“I used a ’65 Deluxe Reverb a lot on the record. And it’s mine. It’s just a workhorse. It is such a great amplifier. It can be a great tool, and it has a lot of playing time on the record. Also, a mid-‘70s 50W Marshall head.

“There was a song, All Rise Again, where I was playing it on the Marshall, and Dave said, ‘You know what? Hold on.’ He went and grabbed a ’61 or ’62 blonde Bassman head and cab, and it gave it that bigger tubby kinda tone. He heard it first. He knew what it needed. As soon as you plug it in, the Bassman gives it that tubby, no-mids-in-sight tone.

Peel back the curtain for us. What does Dave Cobb keep in the studio?

“Dave has tons of stuff. He has a Dumble-modded Deluxe, a blackpanel Deluxe that got used a lot. A late-‘50s Magnatone with that vibrato that will make you seasick. Benji Shanks used a brown Concert quite a bit, which is one of the special circuit Concerts – the early circuit that had five preamp tubes, the 5G circuit. That’s on there.

I used a ’65 Deluxe Reverb a lot on the record. It’s just a workhorse. It is such a great amplifier

“At one point, I think on You Hear Georgia, Dave had an old OR-100, graphics-only Orange head. It was loud as fuck! It rattled every window in the place – and there’s not even any windows! [Laughs] It was knocking stuffing out of the ceiling. But Dave loves that; it’s all about that for him. It’s not about using a plugin. It’s about, ‘Let’s make loud music sound real loud and let’s make quiet music sound real quiet.’

All Rise Again sounds like one of those songs that just magically appears once you come up with the riff.

“Yes. Warren Haynes and I on the phone talking about guitars – who would have thought!? [Laughs] We were all locked down. He said, ‘I’ve written more songs in a month than I have in 20 years.’ I said, ‘Yeah, same here, I’ve done a lot of work.’ He said, ‘Let’s write one.’ And we wound up writing a couple of songs at the time but that, I said, ‘I’ve got a riff that reminds me of you.’ I played for him over the phone, and some of the lyrics. You’re absolutely right. It kinda fell around that riff.”

That’s one of the beauties of songwriting. Sometimes you play, you let your fingers guide you, and all of a sudden you'll get a thought or a feeling, and you’ll think of somebody. Then the lyrics come easy.

“That’s generally how it happens in my case. Sometimes a phrase will come along and inspire you. ‘Okay, that’ll be cool. Let’s make a song about that.’”

I forget who I heard explaining blues tempo, but they said blues is in the back of the pocket, bluegrass is in the front of the pocket. Bluegrass leans forward

There’s a great element of story within your songwriting, and that feels quintessentially a southern tradition. This was something we spoke about with Marcus King a while back. Where does that come from for you?

“That comes from you guys. That comes from Celtic murder ballads and thinks like that. That’s all immigrants coming to the US, and especially to Appalachia. They brought that tradition with them, and it got mixed with African rhythms, and gospel rhythms, and all that became the blues, and all that became rock ’n’ roll.

“At the same time, it is fascinating because there were white people that wound up playing string band music, bluegrass, and then black people were playing string band music, delta and what’s considered Piedmont blues.

“A lot of them were playing the same songs. They were just interpreting them a little differently, culturally. But I think that is beautiful. It’s like, ‘Well, see, there was togetherness even in song.’“

You have just got a signature ceramic slide out and there is great slide all over the record. But why ceramic over glass, or whatever?

“Well it’s not quite as glassy as glass and not quite as brassy as brass! [Laughs] They’re just a little warmer, and they’re heavy. The ones that I like have a large wall. I like them a little more bulky. Some people don’t. Some people like the the Coricidin bottle that’s very light, but I like ‘em weighty. They are porous in side, too, so they stick to your finger a little. They have a little texture there. But I like them all!”

It seems like everyone around the world seems to think that you are a better singer the higher the notes that you can get, y’know! Maybe that’s Bill Munroe’s fault

Some have drawn parallels between bluegrass and shred, and there’s something in that with regards the virtuosity, but how do you incorporate bluegrass and make it sound so relaxed?

“I forget who I heard explaining blues tempo, but they said blues is in the back of the pocket, bluegrass is in the front of the pocket. Bluegrass leans forward. It’s gonna go faster. If it’s fast, by the end of the song it’s going to be even faster. Bluegrass pushes whereas blues pulls.

“There is something about the instrumentation. Bill Munroe is responsible for the bluegrass instrumentation that we know and love but before he refined it to guitar, mandolin, upright bass, fiddle, banjo, there was an accordion there. There was sometimes a harmonica. All that got [removed]. It’s the sound of those instruments all together that is so comforting.”

Do you think that bluegrass, with so much of it being developed live in front of an audience, in large ensembles, sits at the front of the pocket because of all that extra energy?

“I think it was just Bill. Emmylou Harris said it, ‘I don’t know if he invented bluegrass but he most definitely made it fast.’ That was Bill. It was exciting. It’s funny, it’s almost like rock ’n’ roll – play fast, sing high. It seems like everyone around the world seems to think that you are a better singer the higher the notes that you can get, y’know! Maybe that’s Bill Munroe’s fault.”

You guys can all play. How do you stop yourself from overplaying?

“I don’t know even where it came from, the whole ‘less is more’ idea – divide by two. But that’s probably the best advice. I don’t know, but I was around some really tasteful players as a young fellow and a lot of times it is just the limitations that you possess in your hands. I figured out pretty young that I could not play Eruption, so, well, ‘I can’t do that. Sounds great but I can’t do it so I’ll learn something else.’“

Dave Cobb doesn’t use click. He is not going to tune your vocal. There is going to be no cheating. That is why I love the Rolling Stones, because they have never strived for perfection

The concept of ‘divide by two’ is difficult. It’s both a skill and a discipline because you’ve got your darlings, the ideas that are painful to let go of

“That’s happened many times in the studio over the years. On this record, for example, on the song Old Enough To Know, that is live. Vocals and all. A song like that could have been adorned with any number of things – pedal steel, fiddle, harmonica, whatever. But Dave was like, ‘That’s it. That’s the song.’ I think that is a perfect choice. And we all knew it. That was it. It didn’t need a background vocal, a hand clap or anything.”

The talent at that stage of the songwriting process is being able to stop looking at it as your own and look at it as the audience hears it.

“Yeah, you’re exactly right.”

We talked about the Stones earlier. Is that ability to listen to each other and get out of the way on the reasons why those records sound so good?

“Yeah, there’s that middle section of Midnight Rambler, on Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! Keith Richards and Mick Taylor, it’s just the two of them playing, and I remember thinking, ‘Who is doing what?’ Because it is so woven and seamless, and it is so sparse and tasteful. Every once in a while you are like, ‘Oh, that’s Keith!’ One note with Mick Taylor’s lick and it causes this cool thing to happen. They were just playing together.”

You can learn a lot from the Rolling Stones.

“That’s a great lesson. Yeah! Listen to the fucking Rolling Stones! [Laughs]”

It’s the source text for second generation of rock ’n’ roll. If you own Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! and Exile On Main St, play them back to back…

“What else do you need?”

That’s a great lesson. Yeah! Listen to the fucking Rolling Stones!

What makes it so difficult to replicate what we are hearing on those records?

“I don’t know. Maybe, well, it could have had blistering lead guitar all over it, and it doesn’t. And there are songs where, sometimes, you are thinking, ‘Where is Mick Taylor?’ And then you’ll hear him at the very end of the song. ‘Oh, there he is!’

“He’s just so tasteful, and who knows if that is them being tasteful or if it was so many drugs and the surroundings and the situation they found themselves in. But that is what I love. There’s just enough there to make you want more.”

Did any tracks come together in the studio?

“All Rise Again and You Hear Georgia were the newest two. But we had actually run through the arrangement of All Rise Again at rehearsal. You Hear Georgia was a riff. It was a riff and one line of lyrics and I played it for Dave in the studio, he said, ‘What’s that?’ I said, ‘It is a riff. It isn’t finished yet.’ He said, ‘I love it. Go finish it and I’ll record it.’

“I went back to the hotel room and finished it, and that was the most Bob Dylan-esque of all the songs. There was no rehearsal. Nobody knew how it went. The only person who knew who the song went was me and I wasn’t really sure! [Laughs]

“Everybody was on their toes and it went really quickly, very spontaneous, and everybody was very excited. None more so than Dave Cobb. He was the one who said, ‘I think you should call the album this.’ It was one of those moments.”

Sometimes you have got to let the moment author the record. There’s a little bit of that fake-it-till-you make it, because you don’t quite know how it will land.

“I remember trying to figure out how to get out of a solo. We were running through it. The solo jumps up to A. Good old rock ’n’ roll modulation. I was like, ‘Where are we gonna go from here? How are we are going to get back to the chorus.’ He was like, ‘Go to F! The F was made for coming out of A!’ Those are the kinds of moments.”

And a little bit of music theory can go a long way. Going from A to F, that’s a handbrake turn. Do you have a strong background in music theory?

“No, it’s all ear. I mean, we can all pick up a guitar and play a chord and then search for a chord to go to the bridge or whatever, but the theory says, ‘No, that sucks. That’s not right.’ Or, ‘No, that minor won’t work there.’ It’s all about the vibrations that chords produce in your body. ‘Okay, I’m vibrating with that!’

“I never had any formal training. I never had anyone saying, ‘You can’t do that!’ I’ve played with people who have zero theory, and even naturally will play a minor with a major and it doesn’t bother them! [Laughs]”

Some people like pineapple on a pizza.

“That’s right! [Laughs]”

Besides, if there were no mistakes, and if no one broke the rules now and again, our record shelves would be a lot smaller.

“That’s right. That’s another thing Dave Cobb stressed in the studio. He doesn’t use click. He is not going to tune your vocal. There is going to be no cheating. At one point, I remember saying, ‘Well that’s a little shitty there. Let me hit that again.’

“He was like, ‘No! You can’t fake the feeling in that riff. You might make it perfect and it’ll suck.’ And he was right. Sometimes I’ll catch myself thinking, ‘Really?’ But at the end of the day, that is why I love the Rolling Stones, because they have never strived for perfection.”

Perfection is a nice idea in theory.

“Yeah, but it’s boring.”

- Blackberry Smoke's You Hear Georgia is released on 28 May through 3 Legged Records. Pre-order it now.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.