“I broke the cardinal sins of vocal production - five compressors maxed out on a chain”: Iglooghost speaks on his love of Reason, and the seaside town that inspired his chaotic new album

The latest record, Tidal Memory Exo is an uncompromising yet absorbing listen, helmed by one of the most uniquely talented – and unique-sounding – artists we’ve ever spoken to

While there’s much to be said for artists who inhabit their own sonic universe, Seamus Malliagh (aka Iglooghost) not only belligerently defies genres, but – on new album Tidal Memory Exo – bases his music within a land-and-seascape populated by odd half-formed hybrid creatures, the industrial fumes of a forgotten seaside town and the relentless, ever-pummelling waves. The 13-track album makes for one of the most captivating listening experiences we’ve had in a long time.

We caught up with Seamus to hear more about its creation and inspiration, and began our chat by asking about the origins of this concept. “I had been living in this grim seaside town in the south east of England. If you think of a ‘seaside’ town it probably sounds quite sunny and nice – but no, it was pretty brutal. I was inspired by just how stormy it was, and there was all this fucking sewage in the water. It had a really visceral effect. So, I wanted to make something that sounded like where I was living,” Seamus says. “I recorded a lot of it in this abandoned garage squat. It was pretty bizarre and different to the album I made before.”

Malliagh used the town as a canvas in which he’d build his narrative. Waking every morning, Seamus would cycle next to the brutal concrete seafront. “The waves would just be smashing against the cliff. It was horrendous.”

New species

Iglooghost’s wider conceptual universe was first established on his coruscating 2017 debut, Neō Wax Bloom and magnetic 2021 follow-up Lei Line Eon. While these records riff on semi-fantastical themes including tiny gods, portals to other dimensions and bizarre conceptual creatures, Tidal Memory Exo washes up the remnants of this otherworldly menagerie on the drab shores of this grey-skied coastal nowhere town.

With the record’s concept set, the tracks themselves started to form. From the almost metal-leaning abrasiveness of Nemat0de and Germ Chrism to the EDM-ish, New Species across to the dark, hypnotic pulse of lead single Coral Mimic, the record pulls its sonic threads from an array of different genres. “There’s a bit of narrative around the album – a fictional thing that I’ve been working on.

“It focuses around this fictional scene, a hyper-real version of where I was making the album. There’s these warring factions of sub-genres – they have ridiculous names like ‘Post-Coil’ and ‘Germ_Musik’. I think there’s a point where all genres kind of become comedic. I wanted to take that a bit further and avoid that whole modern internet trapping of having to explain your music by using endless tags and descriptions. I think it’s funny to make my own up.”

Despite the multitude of sounds and approaches, a prevailing intensity, and the overarching tidal landscape, adds a cohesive feel to the album. We ask Seamus if he wrote the tracks in the context of them all tying into this one big listening experience? “Yeah, I think I wanted it to be one listening experience. As much as these days you have to think about streaming and stuff. There’s something that draws me in about the idea of a big, meaty album. I wanted the tunes to flow into each other, so you’re not quite sure where one starts and one ends.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Back to the tracks themselves, and first single Coral Mimic’s kick-oriented bass and repetitive synth line bash themselves into your head assertively, balanced by Seamus’ distorted, mesmeric vocals. What was in Seamus’ mind when writing this track?

“Coral Mimic came fairly early. I guess I was quite inspired by Manchester and Factory Records-era productions. I was listening to a lot of early synth-pop (from before it became ‘synth-pop’) stuff like The Human League, the stuff where it was coming off the back of punk really, it was really stripped back.

“I was really intrigued by this weird moment in time – obviously synth-pop became this big thing in the charts and every ‘normal’ person ended up dancing to it. I guess Throbbing Gristle was another noteworthy group of that blip. I was really interested in all that stuff and I was interested in thinking about how they’d make their music if they had the tools that I have today. Which, basically, is just a laptop I suppose.

“Naturally, it all sounds a bit more 3D, but I was definitely trying to approach it with that same sort of ethos. A lot of [what I do] is just layering and layering and layering. Those kicks in particular were probably five different kicks on top of each other. I’m not a super-technical producer. It’s more about music, and my main strength, I think, lies in sound selection. I’m not very good at technical stuff – I still don’t really understand what a compressor is!”

The vocals, a new element for an Iglooghost record, were spurred by Seamus’s desire to get out from behind his laptop: “I just hit this point where I’d been making mostly instrumental music since I was a kid really. Even just performing, you’re just kind of stuck behind this laptop. I was getting bored of this wall that inherently comes with instrumental music. I’d say a large impulse that lay behind putting vocals on the album was that I wanted to get out from behind my devices – and the main computer that I also do my fucking emails on!”

I’m not very good at technical stuff – I still don’t really understand what a compressor is!

Though Seamus admits that he can’t really sing, most of his interest in using vocals comes from the processing. “| think of it as being like a weird space. I want to bring environments into the effects. I did kind of think of things like putting the vocals into a sieve, or rap inside a metal orb or things like that. Then I’ll impart the qualities of like oil tankers and make it sound a bit chrome and rusty.”

So, what precisely did he do to achieve the fizzing, ear-biting vocal textures on the record? “I was mainly processing them by breaking the cardinal sins of vocal production. Having five compressors maxed out in a chain. Putting a gate before that. So it’s all super-compressed and then tons of distortion on top.

“I was trying to see how many things I could chain up while still having the words relatively legible. There’s an excess of stacking. I always like to smell out the runt in the chain and get rid of that. I want everything to be intentional, even if I’m not entirely sure just what it’s doing, or how it’s doing what it does.”

The walled garden

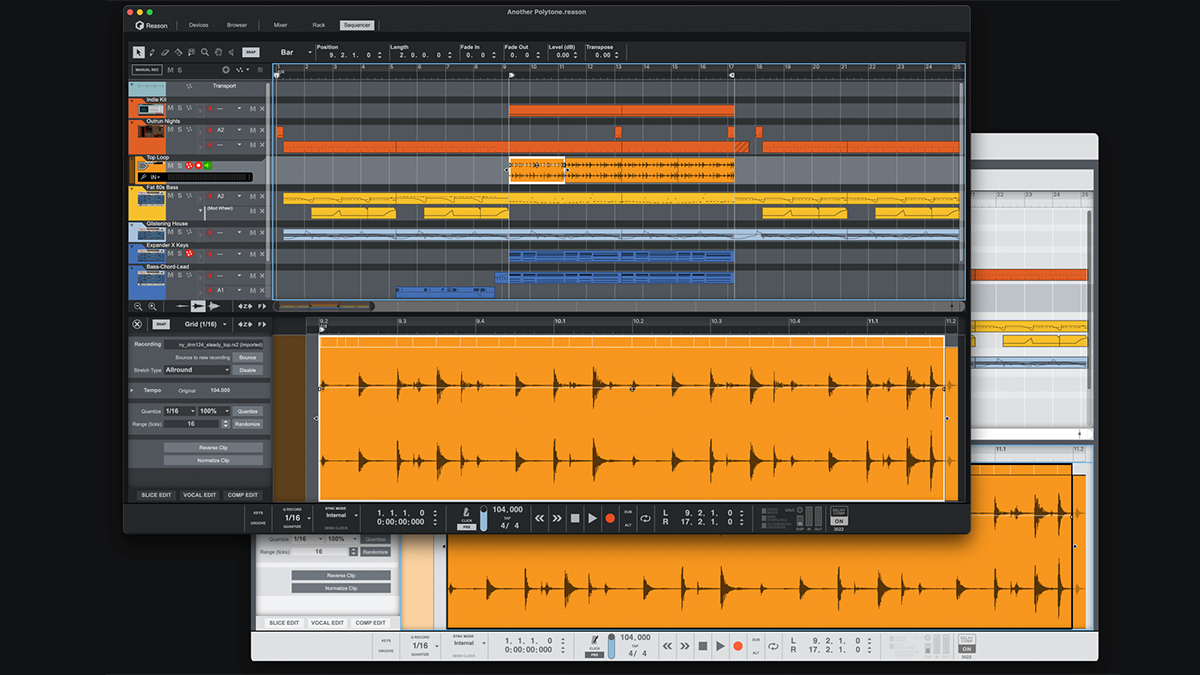

With the album’s diverse range of sounds, and the various colours populating these densely packed mixes, you’d be forgiven for thinking that Seamus used a hefty toolkit of plugins and high-end music production software, but in actual fact, everything was written and produced within Reason.

“I’ve only ever used Reason, which isn’t the most popular DAW, but it’s what I’ve been using since I was a teenager,” Seamus tells us. “Over the years I’ve tried to pick up more pieces of gear, but I tend to end up putting them on eBay a few days later. I just can’t get anything into my workflow that isn’t based on software synthesis.

For half of the time that I’ve been making music I didn’t really have access to plugins. I had to make sounds in really convoluted ways

“I’ve come to accept it at this point. So Reason is all I use. I used a lot of the stock Reason synths. I really like using it because I sort of feel like I’m making music in a walled garden. I can recognise a lot of the sounds and presets, but I guess beyond the Reason-world, people aren’t as familiar with them as say Ableton (Live) presets. Reason has a lot of vestigial remnants of when it was first made back in the early 2000s. Maybe it’s the user-base, not wanting it to change – even the interface is very skeuomorphic, everything is emulating the real physical gear.”

Seamus is open to the (relatively recent) addition of VST plugins to the Reason universe, yet his fundamental approach remains the same. “It was only a few years ago that they added support for VSTs which was pretty strange, because for half of the time that I’ve been making music I didn’t really have access to plugins. I had to make sounds in really convoluted ways.

“I picked up some really sort of backwards processes just to do quite basic things that everyone else could do. But now we do have VSTs, I still find myself making bass sounds the old-fashioned way. I’m using some of the janky old samplers that were probably coded in like 2003. I’ll drop in a WAV file and loop it, whereas I could be using Serum like a normal person.”

Among his favourite recent additions to the Reason stock toolkit include virtual modelling synth Objekt, which was harnessed during the making of Tidal Memory Exo. “It’s just leagues above any other physical modelling synth I’ve ever played with. It doesn’t take very long for you to create a physical-sounding instrument with it that doesn’t exist. You can have these absurd exciters and make bizarre, twangy, physical sounds. It’s right up my street.”

We wonder how long the making of the record took, all-in-all? “It took a good year [to develop] the visual side of things – which is just as important for me – and another year, making sure it was all up to scratch. It’s a bit of a tradition of mine that I do sort of ‘world-building’ around my album concepts. There’s narratives around my albums. It’d be strange for me to just release a record without lots of crazy, extra stuff.

“I want people to experience it in their own way and not put the concept on rails, but it is really important for me to do all the multimedia stuff around it. But it’s important for me to leave gaps and not fill in every blank. I want to be quite ambiguous, so people can interpret it how they want.”

Iglooghost’s graphic design work plays a major part in artistically conveying his concept. It’s a passion that started when he was young, and on album number three it’s resulted in some extraordinary 3D printed sculptures, depicting what he calls ‘prehistoric deep-sea gods’.

Behind bars in Bristol

Though Seamus mixed his tracks as he went through the writing process, the finishing touches for the record were laid down far from his caustic coastal inspiration, yet in a similarly oppressive environment: “towards the end of the process, I moved to Bristol where I am now. I’ve got a studio in a place that was possibly even worse! It was an old abandoned prison. I was literally in this cell. It seemed a bit ironic paying to be in a prison cell. I genuinely had a cage door slammed behind me. I know loads of people like to finish records in places like the Bahamas, but I ended up doing mine in prison.”

We wonder which track took the longest to match the vision he had in his head – and indeed, just when did Seamus know that tracks were finished? “I guess all of the ones with vocals took days and days and days before I was happy with just one line being recorded. I’m not naturally a vocalist, so every time I recorded something that sounded pretty good, it felt like lighting had struck or something.

“It’d be based on some act of God. I’d have a bit of phlegm in my throat or something, and it’d resonate in just the right way to give me a bit of extra growl. It might have sounded more interesting than normal. I was trying everything. Sometimes I’d record some vocals while squeezing my throat or something, so my entire larynx was physically different! I’d be waking up early when I’d be half-asleep. I was trying to get the stars to align by any means necessary.”

In terms of knowing that the track was completed, Seamus reflects that, “I’ve been making really sort of maximalist shit all my life, I think I kind of just have a way of intuiting when there’s too much. I often tread really close to that line. As I’ve got a little bit better at restraint, I can now just sort of tell when every single band of the frequency is being occupied. I just want to hit that saturated point where there’s something constantly happening, everywhere.”

Ghost in the machine

With the album being released earlier this year (on May 10th) we ask whether the next project will continue in the same spirit as Tidal Memory Exo, or whether it will venture off into new environments? “To me this album is such a standard length – it’s a 45-minute listen and I was kind of thinking for the first time ever about chorus-type structures (with the vocal element) There’s much more of a semblance of songwriting poking through, even though it’s not super-obvious.

“I think album-to-album I swing the pendulum and end up doing the exact opposite right after. I have an idea in my head of doing something that has 50 30-second songs. Almost like a kind of spin on jazz music, not the genre as such but more the spirit and ethos.” Considering Iglooghost’s devoted fanbase, we wonder if there ever comes point where Seamus looks at the streaming numbers of his more popular tracks, and shifts his creative direction to replicate their success –and attract higher numbers?

“I think it’s tricky. As someone with some semblance of a career – I mean this is all I do to pay the bills. It’d be way tougher to be experimental if I was a new artist and was trying to get my foot in the door. I do kind of feel a bit conflicted about it; I know it’s easy to be smug about being creative and re-inventing the wheel, but the riskiest thing you can do is to be completely off-the-wall as a new artist but still making it work. Music is always defined by the medium. Albums are however long they are because of the capacity of a vinyl record. It’s nothing new really.”

His awareness of the difficulty that the streaming paradigm places on new creative artists aside, we wonder what advice Seamus might have for artists inspired by his fearless exploration of the grimmer sides of life. “I think you just need to make music that you wish existed but doesn’t. Then you inherently have a niche and are also doing something that is meaningful to you and you want to listen to. Become a fan of yourself. I think that’s important.

“A lot of people would say some bullshit about making music for yourself, but there is always an inherent communication aspect with music and it’s a little bit empty if you’re not sharing it and people are appreciating it. It’s a back and forth, and you need to strike a balance.”

Breaking the ice

It’s a question that we’re surprised to learn he’s not been asked before, but where did the ‘Iglooghost’ moniker come from? It’s a story that takes Seamus back to the very beginning of his interest in music production: “It’s a weird one really. When I was 14 I was really into early Tyler, The Creator and listening back, the beats are quite janky, but there was something really woozy [in the arrangements]. A lot of those tracks were using all these synths I’d never really heard of before.

I had, like, ten names that I went under, almost this fake collective that was all me. It was a fake scene

“I’d never really heard electronic music. I literally downloaded Reason because I heard that some of their biggest tunes were made in Reason, so I wanted to find all the stock plugins and recreate them. That’s how I got into it – trying to dissect this stuff I was really into and then I just ended up making my own music.”

Seamus tells us that at that point, he was already experimenting with made-up genres, and fake scenes – concepts that resonate even now across Tidal Memory Exo. “I had, like, ten names that I went under, almost this fake collective that was all me. It was a fake scene. ‘Iglooghost’ came from that, it was one of the names I went under. It doesn’t really bear any resemblance to what my stuff is now but I never really thought about it – I haven’t actually thought about that in years!”

Tidal Memory Exo is available now on the Lucky Me label.

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

"I said, “What’s that?” and they said, “It’s what Quincy Jones and Bruce Swedien use on all the Michael Jackson records": Steve Levine reminisces on 50 years in the industry and where it’s heading next

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too