“I was the first idiot to get one. I'd lie awake at night dreaming up shit for it to do”: Trevor Horn’s rig that made the ‘80s

We’re all familiar with Trevor Horn’s productions and their preference for expensive, elusive kit, but what got the ball rolling?

Of course, the amount of gear that’s entered and left Trevor Horn’s sessions and recordings over the years is far too lengthy to list. Think of the sound behind Seal, Pet Shop Boys, t.A.T.u and more. But what kicked it off? What about the Buggles, Dollar, ABC and Frankie Goes To Hollywood? Turns out that the genesis of his career as a producer and the trailblazing sound of some of his most famous hits come down to quite a simple setup.

It’s important to realise that in the early days of ‘gear’, and the studios of the late ‘70s, the notion of an ‘interconnected set of equipment that worked together’ was a bit of a distant dream. In fact, anything in the studio that ‘just worked’ at all was a rarity.

Previously, music had been the preserve of the band, existing only in the writer’s and performer’s heads until the instant that they played it out, to be captured by a producer on tape. Thus, any producer who was smart enough to latch onto the emerging technology of the late 1970s and early ‘80s was all set to make a name for themselves and leapfrog the competition.

This is the genesis of Horn’s first ‘rig’ - as he calls it - resident at his home, in a spare room he nicknamed Despair Studios.

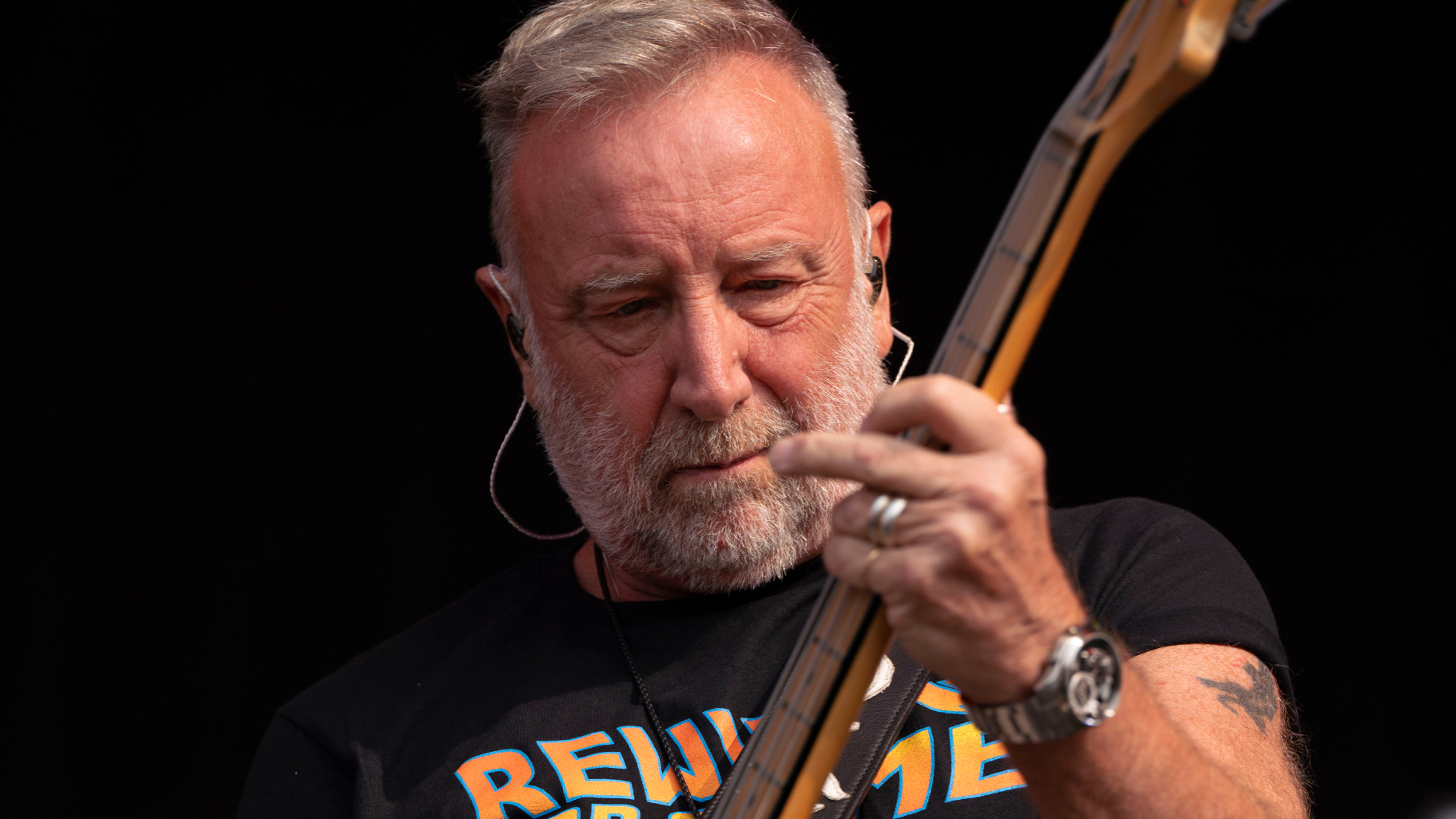

Prior to any aspirations he had to be a producer, Horn was a session bassist and songwriter/producer looking for a break. And that break came via The Buggles alongside keyboard player Geoff Downes as the pair envisioned a dramatic, future-focused, sci-fi aesthetic for their “artificial band”. Working with the latest tech, the duo sought to eschew conventional sounds wherever possible, playing and recording in unique ways to create a sound all their own.

Cobbling together the disparate equipment of the day, the pair used the Solina String Ensemble, Yamaha CP-80 electric grand, Moog Minimoog, Prophet 5 and Roland System-100 to craft their first hit - the remarkably tech-for-the-time Video Killed The Radio Star.

Horn’s Despair Studios rig really took shape with his purchase of Roland’s new-for-the-time TR-808 drum machine and its matching sequencer

While Downes was an excellent player, he experimented with delay effects, producing tight, on-the-beat repeats, creating synth lines that sound for all the world as if they were sequenced despite there being no programming involved. A similarly lo/hi-tech approach was taken for Horn’s distinctive lead ‘radio’ vocal, produced not with effects but via a handheld mic through a Vox AC-30 guitar amp.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

And while The Buggles’ Plastic Age album does sport the Korg MP-7 Mini Pops Junior drum machine, Horn’s Despair Studios rig really took shape with his purchase of Roland’s new-for-the-time TR-808 drum machine and its matching sequencer. While Roland’s 808 legend lives on, memories of its CSQ-600 - essentially an even-more-chopped-down version of Roland’s cash-register-like MC-8 Microcomposer and MC-4 little brother - have long since faded.

The CSQ-600 was produced alongside the 808 in 1980 as its perfect partner. It shares the same build and frame, forming - when used side-by-side - the perfect all-new digital production studio of the time. And it’s this setup that would form the heart of Horn’s first hitmaking kit.

While simplified, the CSQ had a major trick up its sleeve. With the MC-8, individual notes were keyed in as numbers and then, as a separate process, assigned a duration, a grind more akin to filling out a spreadsheet than making music.

While the 808 cowbell has since become a legend, back in 1980 it was deemed useless on account of sounding nothing like a cowbell…

The CSQ, however, had a Gate Trigger feature - as did the 808 - where drum sounds from one of the 808’s three trigger outputs could trigger notes from the sequencer. Thus, timing could be programmed as part of the drum track, saving more than a few hours of brain-crushing number input while delivering the super-tight sound that pushed Horn’s buttons.

Horn would manually play/program in the notes he wanted on his Moog Minimoog via CV Gate into the CSQ-600 - the CSQ had four banks each with 150 note capacity giving 600 in total - and then, with the notes on board, he would take to the 808 to deliver their timing.

Using a sound from the 808 as a trigger - Horn’s choice being the cowbell - he could ‘tick’ through each note in the sequence. It’s worth noting that the cowbell was a popular choice for this purpose as, while the 808 cowbell has since become a legend with a tone all its own, back in 1980 it was deemed useless on account of sounding nothing like a cowbell…

Thus, every time Horn’s CSQ-600 got that distinctive ‘ping’ from the 808 it would play the next note giving rock-solid playback with the beat. All he had to do was remember to turn the cowbell volume knob to zero before hitting play.

Furthermore, Horn’s 808 had been custom modified by synth drum pioneer Dave Simmons to add further triggers. Now not only did cowbell, handclap and accent have individual trigger outs, so did the kick and snare, enabling his programmed 808 to not only drive a synth (via the CSQ-600) but also play a set of Simmons synth drum modules, too.

And it’s this setup that’s all over Horn’s first productions for male/female UK duo Dollar, with 808 drums supplemented by Simmons and sequenced Minimoog synth parts coming via the CSQ alongside plenty of good old-fashioned keyboard playing from Dollar co-writing collaborators Bruce Woolley and Simon Darrow.

Repeating Geoff Downes Buggles tricks, manual parts were often given slapback echoed repeats to create faster, timing-perfect parts. And given the 808’s ability to be sync’d to tape, once ‘striped’ with a timecode, parts could be laid down, the tape rewound then additional parts programmed and recorded alongside, triggering in time with those already on tape.

While Dollar’s first hit, Handheld In Black And White, is essentially the sound of a band playing as mechanically as possible, its follow-up Mirror Mirror is all 808, CSQ, Moog and Simmons, laboriously programmed and triggered perfectly in time.

Horn’s live bass part and keyboards from Woolley top off the machinery, with the glass smash at the end of the intro being similarly manual, as Horn took a pair of spanners to a glass bottle on a tarpaulin to get the sound he required.

And following success with Dollar, and the cheque arriving for US number one Video Killed The Radio Star, Horn’s rig was about to get a major new addition.

For a period of two or three years, me and my Fairlight were the only game in town

Trevor Horn

Ever eager to keep up with the latest kit, Geoff Downes had bought himself a Fairlight, the £18,000 keyboard-plus-computer that put sampling into musicians’ hands for the first time. Sure, the light-pen-plus-screen driven digital synthesis system was cool, and the built-in sequencer was nice, but the real magic was the ability to play back any sound you placed in it. And when Downes departed to join Asia, taking his Fairlight with him, leaving Horn high and dry on the second Buggles album, he knew that he had to stump up for his own.

Fairlights were the preserve of the super-rich, and to make sure his investment got maxed, Horn employed Buggles drum tech-turned Geoff Downes keyboard tech, JJ Jeczalik to work it for him.

"You could rent one but you'd only scratch the surface of what could be done with it. You had to own it, you had to have imagination to do crazy things with it and, if you were lucky, get a JJ to operate it for you,” Horn writes in his autobiography Adventures In Modern Recording. “Having all those things meant that for a period of two or three years, me and my Fairlight were the only game in town.

“I'd tell JJ what I wanted the Fairlight to do and he would work out a way to do it. Sometimes spending weeks working on it. And what that meant was that as the 1980s wore on I was doing stuff with the Fairlight that nobody else had done, and nobody knew how I was doing it. I was the first idiot to get one. Once I understood what it was capable of I'd lie awake at night dreaming up shit for it to do."

Horn attributes much of his success with the Fairlight to Jeczalik’s painstaking work making up for its shortcomings. While the Fairlight was expensive, it was 8-bit, far lower quality than the new 20-bit digital effects elsewhere in the studio, thus Jeczalik and Horn’s engineer at the time Gary Langan would carefully record, layer up, effect and balance sounds prior to them entering the Fairlight. The famous “La, la, la, la” sound on Dollar’s third single Give Me Back My Heart actually started as 16 tracks of meticulously mixed Thereza Bazar vocals before it even hit the sampler.

But it was with Horn’s next project that his rig really got a workout.

While ABC were a tight band, having worked extensively with machines by this time, Horn thought they could be tighter. So while ABC’s first single, Tears Are Not Enough, was good, Horn was determined that their follow-up (and the first 100% produced by Horn), Poison Arrow, would be great.

After listening to its demo. Horn programmed the drums and bassline into his 808, CSQ, Simmons and Minimoog rig, producing a rock-solid backing for the band to play against. By rigidly cloning the programmed beats, the band were able to produce the desired dancefloor feel, and if you listen to the intro and middle eight of the song you can hear Horn’s 808 guide parts showing through as part of the mix.

Add lashings of Fairlight “whizz bangs” on top from programmer JJ Jeczalik, real strings and the newly arrived Roland Jupiter-8 from Anne Dudley and sumptuous Lexicon digital effects and SSL mixing from Gary Langan and you get ABC’s The Lexicon of Love LP - one of the defining albums of the 80s.

By now the 808 had been usurped by Linn’s all-digital LinnDrum, which complemented drummer David Palmer’s playing on third single The Look of Love and, locked to the Fairlight with the new SMPTE timecode. And while gear came and went through 1982, by the time the doors opened on Horn’s SARM West in 1983 his rig was ready to make Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Relax.

Frankie’s debut single had undergone a tortuous birth. A total of three recordings were made, none of which had captured the fire that had prompted Horn to sign them to his new label, ZTT. Never one to get attached to work that wasn’t working, Horn suggested starting again (again) one night in 1983. He departed the studio, leaving Fairlight operator JJ Jeczalik, keyboard player Andy Richards and engineer Steve Lipson pondering what to do next.

Speaking to the 80sography podcast, Jeczalik took up the story. “We had tried many iterations and I’d been collecting samples and bits and pieces. We’d been at The Manor in Kidlington [where Jeczalik had recorded the band jumping into the swimming pool which would go on to be a pivotal ‘feature’ sound on Relax] and we’d been working downstairs with Ian Dury’s band The Blockheads, hoovering stuff up, and we were upstairs in Studio 1 of Sarm West and it wasn’t going well.

Trevor came back and he said ‘What’s that?’ And we said, ‘Oh, nothing…’ like naughty schoolboys, but he said ‘It’s brilliant. Play it.’

Tech/engineer JJ Jeczalik

“It had become a grind and Trevor said ‘I’m going to go home. Wipe the tape,’ and he left. We sat around and Andy said ‘Why don’t we just kick a groove around? Have some fun?’

"So I loaded up the Fairlight with some sounds - the eighth note piano going ‘bam bam bam bam…’ and I had a sample of the word ‘come’ and just sliced the ‘c’ off so it went ‘omm, omm, omm’.

“Andy was playing keyboard [a Roland Jupiter-8] and he was on top form. We had a vague loop on the Linn and Steve Lipson said ‘I may as well get my guitar out.’ He started playing these outrageous riffs and everyone knew we had something ‘cos it sounded amazing. It was just extraordinary.

"Trevor came back and he said ‘What’s that?’ And we said, ‘Oh, nothing…’ like naughty schoolboys, but he said ‘It’s brilliant. Play it.’ And he sat down, programmed up the LinnDrum and we recorded it in one go.”

Alternating manually between just five LinnDrum patterns, with the Fairlight locked to it for the bass, the team were able to jam a backing track together ready for Holly Johnson and Paul Rutherford to add their vocals the next day. History made.

Subsequently, New England’s Digital’s Synclavier arrived in the studio, usurping the mighty Fairlight in time to make Frankie’s follow-up Two Tribes, but by then Horn’s legacy - and the gear that made it - were a locked-in legend.

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.

“Excels at unique modulated timbres, atonal drones and microtonal sequences that reinvent themselves each time you dare to touch the synth”: Soma Laboratories Lyra-4 review

e-instruments’ Slower is the laidback software instrument that could put your music on the fast track to success

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)