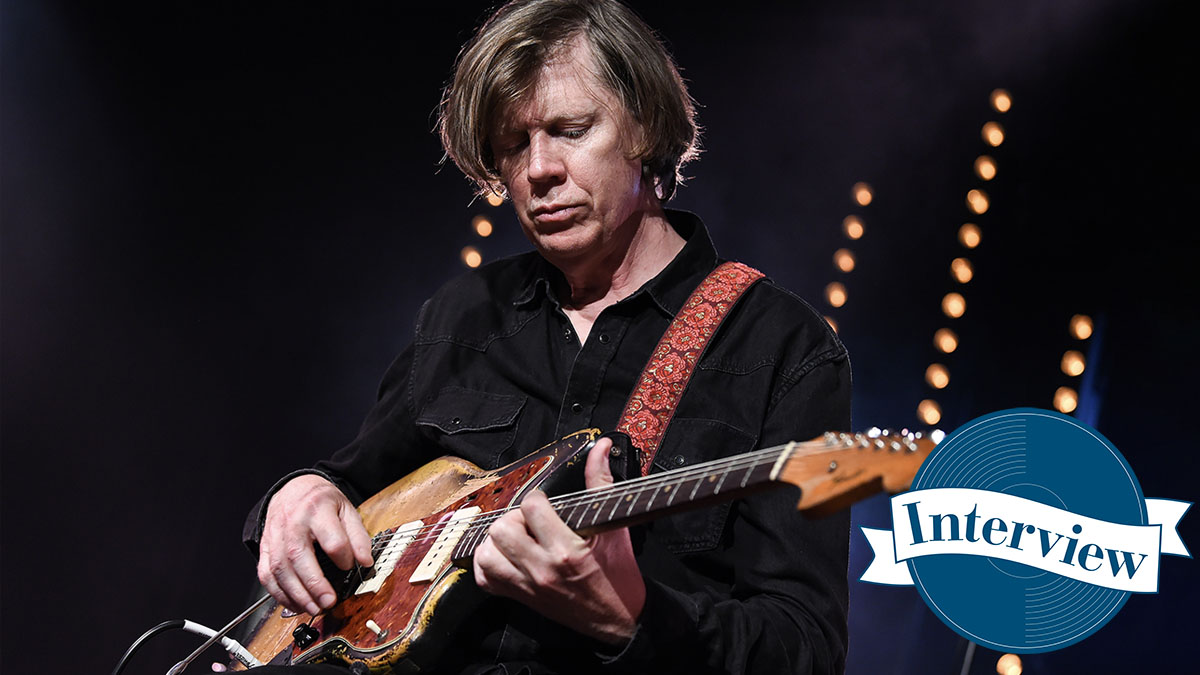

“I really wanted to be accepted in that purist world of punk and hardcore. You plug your guitar in and boom! Instead we had 10 guitars... all broken and rejigged”: Thurston Moore on Sonic Youth, taming feedback and musical epiphanies

Reflecting on a life of warping electric guitar norms, Moore discusses punk's duality, guitar technique, environmental sound, and taking his sound beyond the boundary

Conversation with Thurston Moore is a little like reading his new memoir, Sonic Life, in that it breezes along and is liberally punctuated by cultural references and memories of exhilarating moments when music grabbed him and changed something in him, ultimately presenting Moore with ideas for how he would reshape rock ’n’ roll for a new generation with Sonic Youth.

These moments might include simple pleasures, the primacy of a Kingsmen riff, or the reflexive squeal of electric guitar feedback – the preliminary throat-clearing of any self-respecting punk guitarist’s rig before the first powerchord is hit. Moore is a connoisseur of feedback squeals, admitting that he might release a supercut of his favourites. He is only half-joking.

Or they can be more intellectual epiphanies, such as the appreciation he took from John Cage that all sound held its very own musical potential that the open and aware artist could mine and present in a context of their own.

“To me, first hearing about the idea that all sound has equal value and employing it in composition, that was huge,” says Moore. “That’s huge, and of course it is – it’s beautiful! I always really loved that conflict in the genre of punk rock, that it was either really purist – it’s a one, two, three four, a single guitar kind of thing – or it is like you could just play a chainsaw! [Laughs]”

And these epiphanies can be all of the above; how else could you react to an introduction in nonstandard tuning from Glenn Branca than by engaging mind, body and soul?

Other moments documented in Sonic Life are the observations had along the way, a fly-on-the-wall perspective of a febrile time in music when it seemed like there was an ocean of sound to make your own.

All of this led him here. To a book that was a Joycean epic in early drafts and features an illustrious cast including Madonna, Rick Rubin, Iggy Pop and more. And to a career distinguished by Sonic Youth’s restless evolution, from punk and no wave through avant-garde and alternative rock, or whatever you'd care to call it.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Somewhere between the instinctual and the intellectual, between the deliberate and happenstance, between a respect for bookish technique and a healthy disdain for it, you’ll find Moore’s sensibility – the logic that holds the atonal jangle and skronk of Society Is A Hole and the haunting beauty of Disconnection Notice in equilibrium, all part of the same train of thought, the same search.

I am still kind of resistant to employing traditional technique into writing but I’ve gleaned it certainly. I have respect for it

“I am still kind of resistant to employing traditional technique into writing but I’ve gleaned it certainly. I have respect for it,” he says. “But I have always made the decision that I am not going to let it become an overriding influence. I know that I probably could but I don’t.

“It’s the same point as when a relative of mine, in the 1980s, would comment after hearing Pink Floyd on the radio, ‘Why don’t you guys sound like that?’ Because Pink Floyd was otherworldly and experimental in that whole context of what you would hear on radio – of adult rock – but in some ways [the question] was interesting because we actually could.

“I mean, Sonic Youth could actually morph into doing that kind of presentation, and we have the ability to, and the door is open to it because a lot of people would love to hear us doing that. Possibly. But I would say. ‘I don’t want to throw away my Teenage Jesus And The Jerks t-shirts!’ [Laughs]”

Adopting the principles demonstrated by Branca, Sonic Youth would deploy open tunings, denying Moore the instant gratification of a powerchord but also meaning that he and fellow guitarist/vocalist Lee Ranaldo – and Kim Gordon when she was on guitar, not bass – would need to have guitars waiting and ready in different tunings. They would need more guitars to perform a set and that would cost money.

I remember walking our guitars down Avenue A, by the Pyramid Club, and some leather-clad punk-rock kids were sitting on the streets shouting, ‘Artsy bands rule!’ I thought, ‘Oh man, I don’t wanna be an artsy band. I wanna be part of the gang, punk rock

Of course, the open tunings were influential but so too were the second-order consequences of their approach. Sonic Youth had to dig around for the cheap models, favouring the forgotten Fender offsets, the Jazzmasters and Jaguars, and that in turn helped popularise them as they found an audience.

But as Moore admits here, no matter the desire to reach the frontier of guitar sound he was never a massive gear head. His tone has always been more elemental, not that far evolved from rock ’n’ roll and punk’s formative sounds, reliant on feedback and volume, and manual labour on the strings. That's what matters. That and the ideas behind your sound, too, because if they're strong, even if you can't play, there is a chance you might still be great anyway.

“I find that completely fascinating. I have arguments with loved ones about that, about, ‘How can you listen to music like that when they don’t even know how to play?’ And it’s like, the best bands are the ones who didn’t know how to play,” he says. “The Slits were incredible. I mean, the Slits album, Cut, is one of the most incredible musical statements I have heard in the history of rock ’n’ roll, by musicians who didn’t really have any traditional aspect of playing.”

One of the themes in your career is that you have used your environment, like when Sonic Youth would would take field recordings of refrigerator hum in the bodegas. Location has always been important for you.

To me, first hearing about the idea that all sound has equal value and employing it in composition, that was huge

“I really bought in early on to the fact that environmental sound is to be appreciated and utilised as a sound in music, and that, to me, was always extremely exciting. When you first catch wind of someone like John Cage, you sort of know that name has a bit of gravitas to it. When I just tip-toed into ‘Who is this guy?’ the first thing I heard was a double album of piano music and it was this fractured, minimal piano music, with some of the keys prepared, and I remember thinking it was such a beautiful record.

“Cage is known more for his ideas and his theories, and some of the musical output is just kind of happenstantial to the ideas behind it. In a way it’s like going to see a Jackson Pollock and someone saying, ‘Oh anyone could do that.’ Well, no, not anybody could do that but he did.”

Anything goes…

“When we started, I had a lot of guilt about who we were as a band. I really wanted to be accepted in that purist world of punk and hardcore; you go out and it’s very immediate, and it’s all based on this one implement that you play. You plug your guitar in and just boom! You’re there.

I always really loved that conflict in the genre of punk rock, that it was either really purist – it’s a one, two, three four, a single guitar kind of thing – or it is like you could just play a chainsaw!

“But instead we had 10 guitars that are all broken an rejigged and I felt like that wasn’t purist. There was no boundaries, and maybe there should be some restriction or boundaries to your music just so it doesn’t become wankadelica or something.

“I think I slowly sort of figured out that I was wrong about that, but I do remember walking our guitars down Avenue A once, by the Pyramid Club, and some leather-clad punk rock kids were sitting on the streets shouting, ‘Artsy bands rule!’ [Laughs] I thought, ‘Oh man, I don’t wanna be an artsy band. I wanna be part of the gang, punk rock!’”

You breaking the strings on your big brother Gene’s Stratocaster when you were a kid foreshadows what you would do with guitar. You would break it. Even so, it never gets that far away from a sort of fundamental rock ’n’ roll guitar tone.

“It took me the longest time to buy into the whole pedal culture, that’s for sure. Lee was first with that. Lee was always interested in outboard gear, and even in the advent of computer technology he was interested in word processors, and the fact that there was like a mobile laptop computer that you could actually own.

“I remember him being really interested in that. He’s much more of a gear head than I was. I was never a gear head. I liked the directness of the guitar plugged into the amp, and that was where your true sound was. Nothing was interfering with that.”

I liked the directness of the guitar plugged into the amp, and that was where your true sound was

“When I first joined that band Even Worse, who were part of the downtown New York hardcore scene, I didn’t have a fuzz box or anything. I had nothing. I would just plug into the amp and would overdrive the amplifier, and that was my overdriven punk-rock sound.

“I was maybe a few years older than most of those kids in that scene, and they all used little MXR distortion boxes, or whatever the earliest distortion boxes were – maybe a Rat but I think it was always the MXR.”

The Blue Box MXR?

“It took me the longest while to get one of those. Something about tone for me was the relationship with what you were doing with your fingers on those strings, those pickups and into the amplifier. To hear Keith Richards on the Sticky Fingers record... that was just such a magnificent noise.

“That human touch of Keith Richards’ fingers on the strings, oh my God, and that to me was my favourite guitar sound. It was that. Or just the beginning of so many punk rock and hardcore songs where the first thing you hear is the complaint of the overdriven fuzz box to the amp and it’s just like a squeal and then the recording takes over. I wanted to make a compilation tape of all my favourite beginning-of-song squeals. I think I’ll still do that. [Laughs]”

That is one of the most exhilarating sounds, when you first hear that feedback. It’s like the laws of physics telling the band to hurry up.

“We got really into that fairly early on, certainly Lee and I got into this thing of having the feedback be lines of improvised guitar – almost like saxophone lines. And I remember at the time we didn’t really articulate that. We were just doing it and thinking it sounded pretty cool without it just being this unbridled feedback where you are just in this chaos and then jump on it and do your song.

I always knew that the one thing that would stop us being accepted on the level of the Red Hot Chili Peppers or the Foo Fighters was we would always not be for everybody!

“We were really interested in seeing how long we could actually improvise and actually play with these feedback lines, and I mention in the book about seeing Patti Smith in New York, where Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith from the MC5 comes out, and everybody leaves the stage at the end of My Generation except for the two of them.

“They’re just kind of leaning against each other with this whistle of feedback. It was very slight, and that was a completely remarkable moment for me because they were actually playing and allowing this freedom to happen as well in their improvisation, and it was genuinely astounding to me.

“I could tell that this was something that maybe no one else was hearing with any kind of musical epiphany. But I certainly was. It stuck with me. It was always something I wanted to do more with, and we started doing that with Sonic Youth pretty early on, mostly around Bad Moon Rising.”

You write with a reverence for classic songwriters but you also have this organising principle of deconstructing song. This plays out in Sonic Youth, where you had anarchic noise arrangements and something grand like The Diamond Sea at the other.

“I think The Diamond Sea was interest and intrigue emerging into extended jazz playing and the realisation that, 'Well, we’re not jazz musicians. We are not exactly playing or studying jazz but we are interested in improvisation.' [It was] that aspect of free jazz, avant-garde jazz, or any free-form, open-ended music – like drone music that you would hear from La Monte Young.

“By the time we did The Diamond Sea we had a group ability to play that in our own way, which was very distinct to us as a band. I really wanted the band to be completely distinct from anybody else.

“I remember Mick Harvey from the Bad Seeds came up to me after a gig, and it was right during the time when we would end with The Diamond Sea and we would go off into a 45-minute foray of improvisation at the end, and he was like, ‘Why? Don’t you think that’s kind of unfair to the audience?’ [Laughs] He’s like, ‘You’re taking advantage.’

“I said, ‘No. For me, as an audience member, if I was an audience member, that’s exactly what I would want to hear a band do. I would be really into it. That’s what we’re really into now.’ But I could also see him, as a songwriter in the Bad Seeds. His music always had a succinct quality to it, these parameters in the composition that were a bit more classic. And we would go off and do these extrapolations that were kind of free improvisation.

“I don’t think he found it challenging; I think he found it rather wearisome because it just wasn’t his thing. I don’t think Mick Harvey was going home and listening to Sun Ra records or Albert Ayler records. So it’s not for everybody and that was always okay with me as well, and I always knew that the one thing that would stop us being accepted on the level of the Red Hot Chili Peppers or the Foo Fighters was we would always not be for everybody! [Laughs]”

Sometimes the audience wants to be challenged. Sometimes it needs to be. Your noise set at the Southbank as part of Yoko Ono’s bill sent lots of people to the exit and it was brilliant.

“That was a pretty bad gig but I am glad you said you liked it because most people thought we stunk up the room.”

Well, you did! But there was something agreeably alien about that setting, in a room so bright.

“[Laughs] I remember! That was an unfortunate night because I have played with all those players, and those were heavy cats on the London improvised music scene, but the way were set up in a row like that as opposed to being semi-circular and facing each other, like, nobody could hear each other, and it was formless and forced. I realised immediately, ‘This isn’t working.’ Because I couldn’t hear anybody, and I knew that was kind of ridiculous.”

It’s interesting getting the artist’s perspective on that. Improv always is a high-risk endeavour, you at least have to enjoy that risk knowing that the rewards are contingent on various factors.

“Yeah, well you know when it’s working because it’s just really organic. You trust your own sensibilities and you also trust the group’s sensibilities because those are the people you are playing with, and all of that has to be working. Once it starts to become forced it is going to be a drag for everybody, the players and the listeners. But Lou Barlow from Dinosaur Jr said in an interview, ‘I don’t like bands that are perfect all the time.’ And I kind of agree with that.”

Some bands play right on the edge and right over it.

“It was the same thing with Nirvana. I remember seeing Nirvana gigs early on before people talked about them. They came here and played the Pyramid Club or whatever, and it was a notorious gig where they were just terrible, and everybody was there because there was a bit of a buzz by that point. ‘Oh yeah, these guys are supposed to be the shit!’ Even Iggy Pop was there.

“The place was packed. It was during a new music seminar weekend. I had seen them destroy, so I knew that they were going to be great, and they were not great. In fact, from beginning to end it was really just like they weren’t together. They were bored. Kurt seemed like he was in a bad mood and he ended the set by pouring a pitcher of beer over his head, and it just fizzled and he skulked offstage.

I think that whole concision in the music came out of being informed by the Ramones, and the earliest punk sounds. There was a certain identity in keeping things short and sharp

“It was a hot summer’s night. I remember talking to Iggy Pop outside and going, ‘They’re actually really good. You should come back and see them some other time because they are a really good band.’ And he goes, ‘Oh, man! I thought they were great! Yeah, yeah, yeah, when he poured that beer over his head… I’ve never seen anybody do that before.’ I was like, ‘Yeah. but…’ [Laughs] That’s not what they’re about. So the greatest bands in the world can be terrible. The Beatles must have had some shite gigs. [Laughs] Who knows!?”

No one could ever hear them over the audience. They became a studio band for the most interesting part of their career.

“Yeah, the New York gig, at Shea Stadium? It’s like the sound system was a basement noise gig sound system but at Shea Stadium.”

You mention City Gardens as being the rowdiest venue on the east coast. What was it like in those days?

“It was outside of any residential area or even any kind of civic part of Newark. It was in the middle of this industrial landscape... a typical New Jersey, harsh hardcore environment. It wasn’t really scary or anything. It wasn’t the only club that was like that either across the USA. It was generally a better idea to have your venue be away from any complaining residences.

“When we played there, it would be us and Dinosaur Jr and Das Damen, Red Cross, our gang of people. We weren’t into sort of heavy metal, hardcore, punk thug slam dance mosh-pit action at all, so the nights that we would play there would be a bit more congenial, y’know! But I think I had gone there a couple of times to see Black Flag; it brought out this whole sort of cement-head contingent who just kind of wanted to throw their fists in the air and bang people around.

“That got more and more into this thing of testosterone-charged young lads who had yet to have experienced sex with anyone else, so it was like they had to let it out somehow! J Mascis always had this theory that as soon as people who listen to hardcore and punk rock at that age, as soon as they got laid it stopped. [Laughs]”

For all the ferocity – and the testosterone – that era of punk had some great songwriters. They were so concise but created entire worlds for our imaginations to wander into.

“Right, the whole idea of economy was really important. I remember interviewing MDC, aka Millions of Dead Cops, the hardcore band. I was doing it with Jack Rabid, who was the drummer of Even Worse, who still puts out his fanzine, The Big Takeover, and I was sitting in his apartment with him, interviewing MDC.

“They said something to the effect that the reason their songs were so short is because we’re running out of time! The world doesn’t have much time anymore. We’re running out of time so we have to write these short songs. That’s pretty poetic for a Texas hardcore band that now lives in San Francisco. Interestingly enough MDC all became hippies.

The brevity of punk songwriting requires its own brand of discipline.

“I think that whole concision in the music came out of being informed by the Ramones, and the earliest punk sounds. There was a certain identity in keeping things short and sharp, the energy of punk rock.

Whenever I see these documentaries about punk music it is always about, ‘Y’know, it was all about the slam pit, and it was all about this trouble-making, and this attitude... What we were wearing.’ Nobody ever really talks about the songwriting

“Like the Clash. I remember Joe Strummer talking about first seeing the Ramones and thinking it was going to be this squall of New York Dolls junkie rock but instead it was this really militant one-two-three-four, verse/chorus/verse/chorus, "Bye!" Next song. Without a break, just a step-on-the-fuzz box, feedback squeal and onto the next song.

“That was a template that made a lot of sense towards this new energy that was going against the extrapolated sort of hippy, strung-out sort of sound, so I think it was very useful. And it also allowed for amazing, brilliant songs.

“Hong Kong Garden [by Siouxsie and the Banshees]. Spiral Scratch [Buzzocks EP, 1977]? I mean, my God, all those first singles and seven-inches from ’76 to ’81 or whatever, it’s incredible how great those songs were, and I felt that same way even when the hardcore bands started coming up with a one-buzzsaw kind of vocabulary but there were so many good songs. Minor Threat songs? Just fantastic.

“Whenever I see these documentaries about punk music it is always about, ‘Y’know, it was all about the slam pit, and it was all about this trouble-making, and this attitude. And it was all about what we were wearing.’ Nobody ever really talks about the songwriting and for me it was sort of an impetus for the book I wanted to write. I wanted to write about songwriting more, but it guided me into this territory of, ‘No, write about Sonic Youth. Write about your history.’”

If you were to teach guitar, what would be the first thing you would put on the syllabus?

“The first thing I would do would be to ask every student to create an interesting tuning, an open tuning, on their guitar then bring it in and let’s collaborate as a community to see where we could go with it. That would be a blast!”

It’s funny how you denied yourself the pleasures of a powerchord with open tunings. You would describe your writing process as waiting for something musical to come out of it, like the surfer waiting for a wave.

“For me it’s just like everyday practice is essential to being an artist or a musician. If you are writer, you write everyday. If you are a painter, you paint everyday. The painter Gerhardt Richter wrote that the daily practice of painting makes him a painter, and I think there is this idea with being a musician where you play everyday.

“Your instrument, whatever it is, you play it everyday, and you are at one with it, and it constantly keeps you in the moment with music, and also you are constantly progressing as a student of the music. But I find that actually stepping away from it, and allowing time to go by without acknowledging it, or playing any music whatsoever, and then coming back into it, like, there’s this kind of meditational generation of ideas that comes out that wouldn’t come out otherwise.”

Meditation is really important in the creative impulse, and I find it by letting the guitar stand for a couple of weeks... when I pick it up it is a really wonderful reunion

Sometimes you need to take a step back from it and have a bit of space and come back to it fresh.

“I find it really rewarding. I’m not saying that’s a good alternative to practice but I find it personally to be very interesting. Meditation is really important in the creative impulse, and I find it by letting the guitar stand for a couple of weeks, and I am not going near it, and then when I pick it up it is a really wonderful reunion.”

- Sonic Life is out now on via Faber & Faber.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)