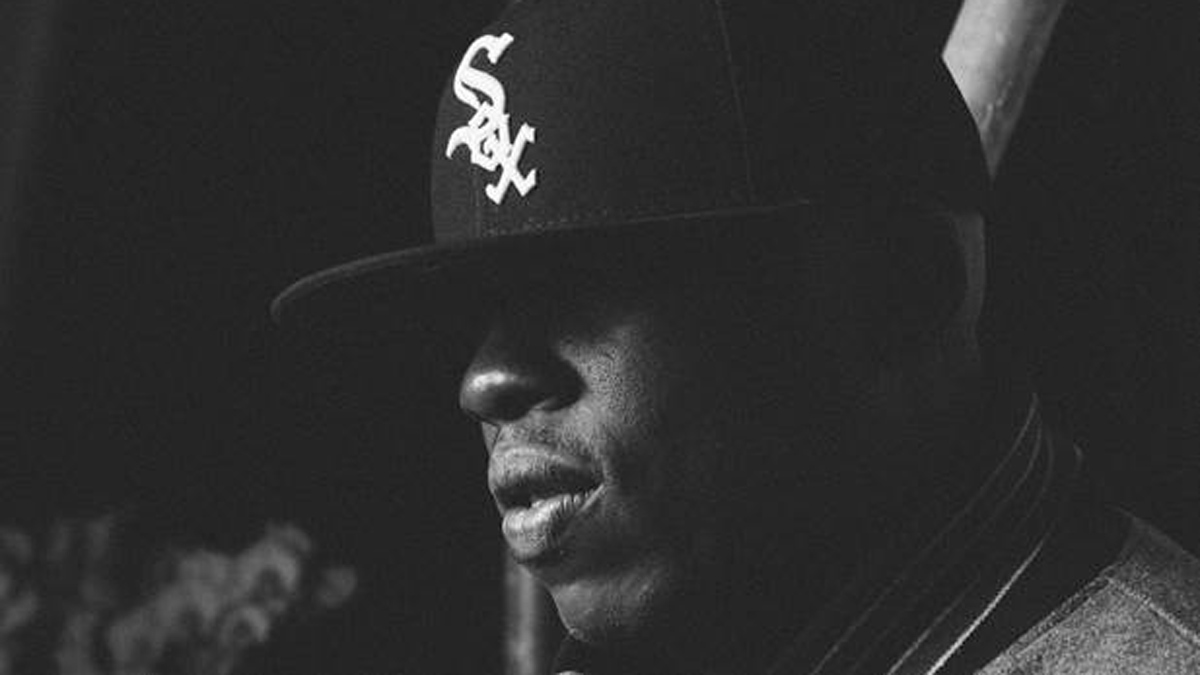

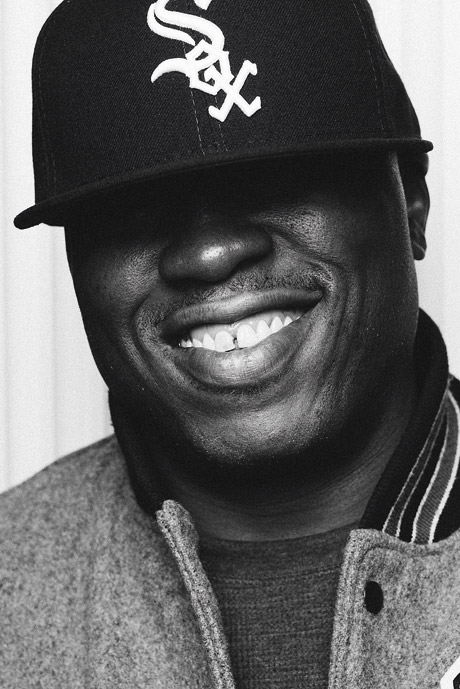

"I feel like some DJs out there are making a ton of money and don’t know how to DJ": Mike Dunn on the evolution of house

We caught up with the humble Chicago house innovator

Chicago house may be rooted in the past, but its effect on dance music still ripples through a breadth of sub-genres excelling far beyond the shores of Lake Michigan. Raised on the skill, passion and dexterity of a small group of hugely innovative DJs and producers, Mike Dunn absorbed their artistry in person and went onto become a prolific producer in his own right.

He began DJing at block parties in Chicago’s Englewood, spinning reel-to-reel tape decks alongside two Pioneer 707s and a drum machine. Before long, pivotal releases such as Dance You Mutha, Magic Feet and Face The Nation surfaced across a variety of pseudonyms.

Intent on bringing the acid back to house, and lacking the cynicism one might expect from a DJ that’s been dunked in the music industry’s shark-ridden waters on several occasions, Dunn is back with his first release under his own name for 27 years, titled My House From All Angles.

How do you think house music has developed over the 30 years since you first got involved?

“It’s had its ups and downs and been through a lot of trials and tribulations. At the beginning, it was just about us playing around and trying to make stuff to play at parties, then I figured out it was a business after we discovered a lot of us were getting robbed. It was down to us to develop fully as producers and understand how to make the records, but there was a period around the new millennium where I felt house music had lost its way. It started getting faster and harder and lost its vibe, its funk, its soul. The best time for house was right at the beginning - the early 90s going into the mid-90s. Back then, there was this whole community and the house nation was connected worldwide, but somehow it broke off and there was a gazillion genres.”

It seems that once a genre becomes popularised, it gets exploited and can lose its essence…

“I agree, and I wish we would have been smarter businessmen in those early stages, but we were just wrapped up in the love of doing it and hearing our track on the radio or in a club. We didn’t think you could make a living off of it. Like I said, we found out later that there was a lot of money being made, passing through people’s hands and missing our hands.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What was it like DJing with legends like Larry Heard, Armando and Ron Hardy?

“And Frankie Knuckles. I did several parties with Ron Hardy, but I’d say the difference between Ron and Frankie was that Ron was a great programmer rather than a great DJ. He knew what to play and when to play it. Frankie was more on the technical end, blending the records and making everything fit together. So I took more towards Frankie, but only because I’m a tech guy. I won’t just buy something because it’s the new thing; I’ve got to know how it works and why it works that way - and how I can make it do something different. As a kid, my grandmother bought me a record player component set - that’s old-school, by the way. It was all-in-one - the turntable, amp and the speakers - and I remember her being extremely upset because within two weeks, I’d opened it up and taken it apart to see how it worked.”

You were one of the last people to DJ with Frankie Knuckles…

“I played with Frankie once before he passed, which was one of my lifelong dreams. And then there’s Armando, who was my running buddy. He was like an emotional genius because he knew how to get people out to the parties. To this day, I’m like a sponge. I like to be around people so I can get to know what they know. One of my favourite DJs of all time is Louie Vega. I like being around him just to watch how he works. I love all his productions - they’re impeccable and that’s what I strive for.”

What techniques were you using to DJ back in the day?

“I used to bring two reel-to-reels to the parties, back when you used to cut tape. Eventually, I was barely playing vinyl and just spinning tracks from reel to reel. We didn’t have Pro Tools, Ableton or Logic; we had to do what we called pause editing, which was using a cassette deck with a tight pause button. So just imagine, kiddies, if you heard a sound repeat five times, we had to record it five times, not cut and paste five times. Unfortunately, we didn’t get recorded back in the day, either, which was a major mistake. Back then, you didn’t want other people to have your edits in case other DJs cut it out of your set.”

Does DJing as a technique-based skill still have value, or has modern technology made that element of it redundant?

“At the beginning, I was one of those mad DJs that thought, ‘This computer stuff isn’t real, it’s cheating’; but what I realised was that I’m still a tech guy and you either move with the times or the times will move without you. I learned how to use technology to my advantage instead of using it as an excuse. I wondered how I could make it work and still be authentic at it. I went through that whole phase with Serato and using a CD player to make it feel as though I was still playing vinyl and still performing. Once they’d made that, I was sold on the whole rekordbox and CD drive thing. I guess some of the younger cats don’t realise that to travel with so many records all the time is really tiresome. Until you’ve been through losing your records on a flight and having nothing, you won’t understand. They’re almost impossible to get again, so I realised I needed to keep those safe at home. Basically, as long as you’re playing a good set and good songs, the people on the dancefloor don’t care what you’re playing them with anyway.”

Did you ever envisage DJs would become the global superstars they are now?

“No - like I said, we had no understanding of the business and knew nothing about Europe. We only thought our records were being sold in Chicago or New York. I didn’t know that a whole other part of the world was going crazy over this sound we were doing until Tyree and Kool Rock Steady came to the UK and did Top Of The Pops. They did Turn Up The Bass, then Tyree called me and said, ‘Man, it’s crazy over here; our records are selling in all the record stores’. That’s when I found out there was a lot of money being made that nobody was telling us about.”

Until you’ve been through losing your records on a flight and having nothing, you won’t understand. They’re almost impossible to get again, so I realised I needed to keep those safe at home.

What direction would you like to see DJing head in?

“Like I said, I don’t wanna be that grumpy old guy that doesn’t let technology flourish, but I just feel like some DJs out there are making a ton of money and don’t know how to DJ. Is the reason they’re making all this money because they’re DJing, or because of who they are and what they’re playing? That’s where we start bumping heads, but that’s also a whole other fan base. They may play some of our records, but it’s not our lane. I don’t fault anybody for getting what they get, and I’d like to make a ton of money spinning, but we have to ask ourselves what we can do better to get young people interested in our sound. At the beginning of house, that’s what it used to be to us: fashion and culture, but we kind of lost our way because it’s no longer cool to be house.”

You launched your label, Blackball Muzik, in 2013. Was that just to publish your own music or inspire others as well?

“Blackball Muzik comes from when I left Bad Boy Records and Puff Daddy. When the deal was dropped, I did another song with Universal Records and found out that I was being blackballed in hip-hop. I’m not going to say no names, but every turn I was trying to make the doors were getting shut. So when I came back to house, I thought it was only fitting to name my label Blackball Muzik. But as I always say to the young cats, don’t ask me why I’ve stayed around so long - ask me how. If you ask me why, you’re going to get some sarcastic shit.”

Why did it take so long to release another Mike Dunn record, and what’s the meaning behind the title, My House From All Angles?

“Throughout my whole career, I’ve done a lot of pseudos, like The MD Xpress, The Jass Mann and QX1. I’ve always been a humble cat and don’t wanna have a whole lot of records out with my name on, so I would make up names and just say it was produced by Mike Dunn. I wanted to be known more as a producer than an artist. But this album is like all of my pseudos rolled into one project, which is why I called it My House From All Angles.”

How did you approach bringing all those styles together under the one roof?

“When I started this record, I thought the tracks were just OK, but then I began sending them to my manager and he was like, ‘Fuck, D, these tracks are getting better and better’. Instead of rushing it, we just kept doing more and more tracks and swapping them out, but it got to a point where if we kept doing that, it would have gone on forever. Some of the tracks were supposed to be for Defected, but we ended up pulling them back and using them for this project. I want to get the younger kids into it and pull that crowd into our world. They don’t have to live there, just know it.”

You have some strong acid house elements in the tracks, and it almost sounds like that’s come full circle?

“I’m hoping so, and I’m hoping that the way I did it on this album will spark more producers to do it that way, too. Some people think of acid as just a noise, but it has to have a vibe to it. It can work if it’s done correctly. When we were making those tracks, we actually programmed it all in just like we used to back in the day. You can see the smile on my face when it comes to using all that technology, but what makes a good house track is simplicity. What people don’t understand is that one sound is always playing off another. That’s what makes house music house music.”

It’s a very analogue-sounding record, so we take it you’re still primarily using hardware…

“Thank you for asking that question. That was the whole concept of the album, and I went back to using all my hardware stuff. You see, the mistake I made was that when I started using software, I sold all my vintage gear, like the Juno-106 and my Roland TB-303. I thought the computer had everything I needed. I’m still upset when I think about everything I got rid of, but I did keep some pieces. I also went online to try and get back a lot of the vintage stuff I’d sold, but I had to pay a little bit more and there was stuff I couldn’t afford. But I’m not going to pay anybody $4,500 for an 808 or $3,500 for a 909 or a 303, when I bought one for less than $600 back in the day. The great thing about what Roland did is that they came out with the Boutique versions, which sound amazing.”

How do you feel they compare to the originals?

“They sound just like the originals, and I’m more into the sound than how they look. To get to the point, I wanted the album to have a real analogue feel, not running soft synths through plugins to try and make them sound dirty. I wanted the album to sound raw and not polish the sound too much, and for it to have that warm, thick sound. I mean, there’s a lot of plugins that sound really close to the hardware and are extremely good, but I didn’t want to be looking at a screen or grabbing a mouse; I wanted to look at a module and turn some knobs.”

So you wanted to have a performance-based approach, just like back in the day?

“Yeah, because using software is not the same - it’s just night and day. You got the 303 plugin and you’re using controller knobs and trying to assign CCs to it, but no; when I use the TB-303, I’m just messing with stuff on-the-fly. It made me feel young again to produce in that way. It took me back to a time when Armando and I were back in the studio together, working on stuff. It felt good and it felt right.”

Presumably, computers and software do play some role in your production process.

“Recording, sequencing and mixing. I love using Logic and Ableton. I produce more of the musical stuff on Logic, and Ableton’s just so quick that if I want a delay I’ll just drop it in. But I have a hybrid system, so I’ll use both hardware and software. I use a lot of the Dangerous Music stuff and have some high-end mic preamps, compressors and limiters. I also still have some of the old DBX stuff. But I mostly use software for audio processing, because I don’t know where my delay time sheets are, which is what we used to have in the studio and would tell us all the right numbers to get the right delays.”

How do you plan to support the album live?

“Pioneer, if you can hear me, I need some things: They have this thing called the XDJ-1000, and I’d love to do some of the album on the fly with that. It’s like a Nexus 2000 NXS2, but you can actually program stuff while you’re playing and lock it up to whatever you’re bringing in. Otherwise, if I do a live, one-man-band thing, it’s going to get kind of complicated. Ideally, I’d have two or three cats doing stuff, but unless the album really takes off, I don’t think anyone’s going to pay for that [laughs].”

My House from All Angles is out now on vinyl from MoreaboutMusic.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

“Turns out they weigh more than I thought... #tornthisway”: Mark Ronson injures himself trying to move a stage monitor