Hot Chip's Joe Goddard on vintage synths, leaving the home studio and an underlying love for disco

Impressive synth line-up adorns new North London studio

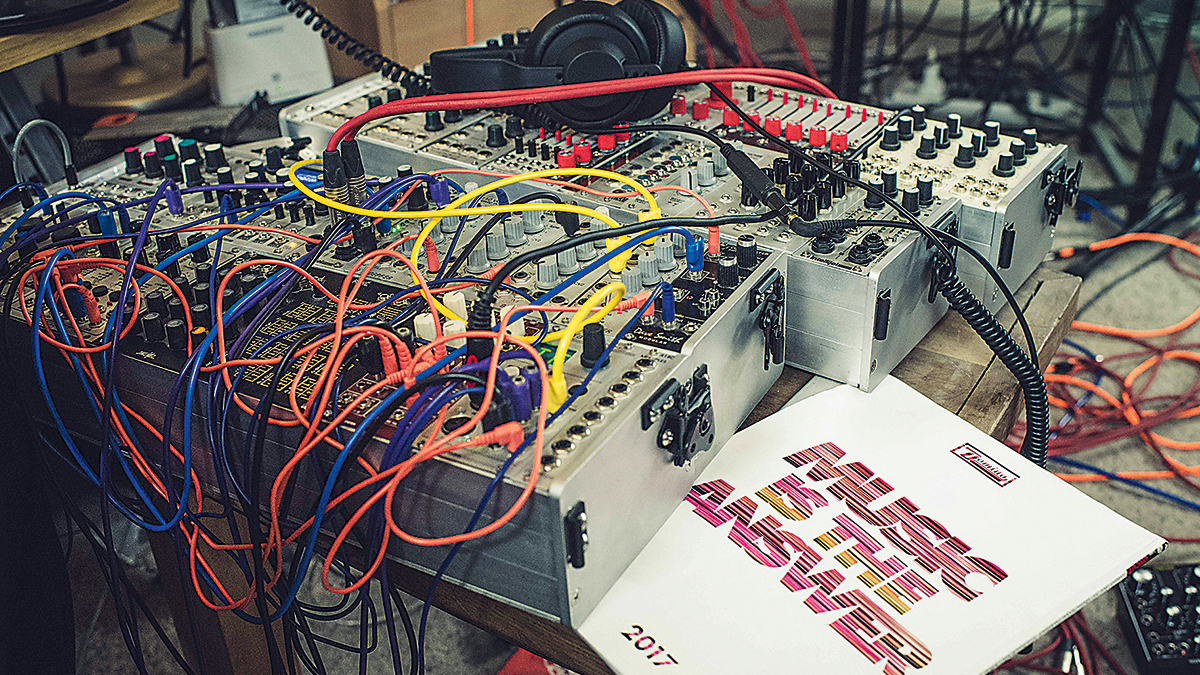

Joe Goddard – alongside Alexis Taylor, one half of Hot Chip’s main songwriting duo – has finally set up his first, proper studio. Tucked away in a quiet street in trendy Hoxton, North London, it’s littered with analogue classics, odd percussion doo-dahs and a comfy sofa dead centre of the ATC monitors.

Among the synth line-up, there’s a CS-80, an ARP 2600 and the always impressive Roland System-100. Having all this hardware holding hands with Cubase and ready to go is still a bit of a novelty for Goddard. For over 20 years, he was working out of cramped bedrooms and spare rooms, patching and un-patching gear as it was needed.

So, what prompted the move? “Two young children,” laughs Goddard. “I’ve never minded working from home, but as the kids got a bit older, they started getting more and more interested in Dad’s special room. Every time they came back from school, they’d run in to see me and start messing about with every button and knob they could get their hands on. Then, they’d take control of the chair, spinning each other round until they’d fall over.

“It all came to a head when I was recording some vocals with a young female singer who was quite nervous in front of the mic. She was trying for the perfect take and my two were hammering on the door shouting, ‘Let us in!’

“The time felt right.”

The Hoxton studio is where you put together the recently released solo album, Electric Lines – the long-awaited follow-up to 2009’s Harvest Festival. There are recognisable hints of Hot Chip, but solo, there’s even more pop catchiness and 70s disco warmth. A sort of funky, electronic Abba…

“I like that! Abba are one of my favourite bands. And you’re right about the disco ‘thing’. I play a lot of classic and new disco when I’m DJing, and it always gives me a lot of pleasure. I like the energy and feel of disco – the push and pull of that live groove. It’s no surprise that, when I’m in the studio, I naturally gravitate towards that sound. It’s always somewhere in the back of my mind when I start a track.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

I’m sure I can remember reading somewhere that the human brain can tell within 30 seconds whether a song is fully quantised and bang-on every time.

“With the Hot Chip stuff, there’s a lot of live playing – bass, guitar, keyboards – which gives a song its natural looseness. But even on this album, which is mainly programmed, I tried to avoid hitting quantise all the time. Obviously, there are times when that über-quantised feel really works, but it’s important to use your judgement with each track, instead of it being your default setting. This album was all about getting off the grid. As everyone reading this magazine will know, it’s sometimes the imperfections and the looseness that will give a track its identity.

“I’m sure I can remember reading somewhere that the human brain can tell within 30 seconds whether a song is fully quantised and bang-on every time. Like I said before, that might be what the song needs, but the brain will recognise this and… switch off. If you add live instruments or move things about a bit, you can catch the brain off-guard. It keeps the listener engaged.”

Is solo songwriting very different to Hot Chip songwriting?

“Not really. Fundamentally, the basic building blocks are the same. With Hot Chip, I put together a rough demo, send that to Alexis, who adds lyrics, and the whole thing gets finished off by the band. With the solo stuff, I put together the rough demo here and then… I finish it here. Recording all the vocals here, too.

“There was one track that I sent to Alexis for vocals and, if I’d done the same with the rest of the songs, it would have ended up being a Hot Chip album. The starting point is always the same – I go into the studio and try to make music that feels exciting.

“Now that I’ve actually got everything patched up and ready to go, I often found myself switching on in the morning, programming a few things in MIDI and then sending it out to a bunch of analogue machines. Having the 808, the 606 and the System-100 running… jamming for an hour. Wind the volume up a bit and you just get lost in the groove. It’s endlessly inspiring.

“Then I’ll add a bit of CS-80, send stuff to the Eurorack, maybe a bassline from the ARP. With each instrument, I’ll do three or four passes of the whole song, playing alternative lines, change the chords a bit, different textures, get stuck into the controls with some real-time tweaking.

“It’s all recorded, but because I’ve got all those different takes, it gives me some extra room to play with; I’m not fully committing to ‘this’ version of the song. I still have options.”

Was it all hardware synths on the album?

“Not at all. I don’t have anything against modern sounds and I don’t have a problem with using plugins… the Arturia classics, Omnisphere, Chromaphone. If you refuse to use anything but analogue, you’re in danger of creating a pastiche of 70s and 80s electronic music. The real joy is bringing them together – old and new, modern and vintage.”

The Eurorack setup is right next to the mixing desk…

“Because it gets a lot of use. You’ve got the fun and games of all those manual controls, but you can do way more with the sound than you can with an analogue synth. In a sense, you can start forging your own sonic path and creating sounds that really are unique. They’re your sounds.

“I’m so excited by my Eurorack setup that I’ve actually started dreaming about different patch configurations. What if I go from there to there and back into this and over to here? I wake up and I can’t wait to get in the studio. The thing about real knobs and sliders is that they’re… fun. You’re creating, but you’re having fun at the same time.

“And once you start adding software into the equation – the next big change for me is using Expert Sleepers to control the Eurorack – you can really start getting into some complex sound architecture. A sort of hybrid synth sound that brings together the precise quality of a plugin with the loose dynamic of the module.

“In terms of the next stage of studio technology, I think that’s where the real action is.”

Rumour has it that you’ve been with Cubase for… well, forever.

“Not quite. I started off with Cool Edit, but switched to Cubase about 1995. I was lucky because my dad used computers for his job, so I grew up with them. I remember the Spectrum, the Atari, then a very early PC. I never got into total nerd mode, but my dad used to edit pop videos and I watched him move from 35mm onto the computer. It seemed very natural to make music on computer and I immediately saw the computer as a creative tool.

I can play a few chords on the guitar and tinker around on a keyboard, but once I started working with the computer, it opened up all these possibilities.

“We sort of formed Hot Chip when we were still at school, but it started out as mates sitting around playing guitars and some cheap keyboards. Unfortunately, I was never a particularly good musician in the traditional sense. I can play a few chords on the guitar and tinker around on a keyboard, but once I started working with the computer, it opened up all these possibilities.

“At the time, I was listening to a lot of hip-hop and, with very limited equipment, I could start making songs that sounded a bit like the stuff I was buying – programming some simple beats, adding a few samples. You could get an almost immediate satisfaction that seemed way more tempting than sitting around for a month and trying to work out a bunch of guitar chords.”

What was the first album made on?

“It was quite sweet, really. There used to a be synth shop in Angel, North London. We were always hanging around there, wondering if they had anything we could afford. One day, we saw this thing called a Teisco… an Italian company who, I think, also made kettles. That was Hot Chip’s first proper synth. Then there was a very basic Casio thing that had some lovely sine waves. And a bunch of shakers, rattles and toys that we got from the Early Learning Centre.

“Somebody lent us an MPC and I think that’s when I really started immersing myself in MIDI programming. I found immense joy and satisfaction in programming beats and melodies on the screen, and that’s still where I find most enjoyment.

“I’ve been doing this for quite a few years now and there are some mornings when I come into the studio and think, ‘What’s the point of trying to make a new song?’ I’m sure I read somewhere that there are something like 20,000 new songs loaded up to Beatport every week. Imagine that – 20,000 new bits of music.

“When you’re faced with a blank screen and you’re trying to create something that people will listen to, it can be seriously daunting. Some people will get inspiration from a loop or an audio sample, but I generally like to start clicking on the screen. ‘Let’s put something there, there and there, and move this one so it’s not quite on the beat.’ I like the fact that I can see those dots on the screen and I can send it out to a bunch of different synths and drum machines. For me, it’s the quickest way of getting the idea from my head to the computer.”

There’s a lot of gear in the studio. How much of it do you take out for the solo live shows?

“Not much. It’s quite a simple setup, really. Some live vocals, but the real root of it all is Traktor stems – four stems for each track. Obviously, there’s a lot of messing around with that audio… looping, effects, weirdness. There’s also a modern 808 and 303 – the TR-8 and the TB-3. As well as adding drums and acid lines, I send the 303 to the Eurorack for some more analogue madness.

“Then there’s a Kaoss Pad to really push things over the edge and add a nice visual element. People can actually see you attacking a song and instantly hear the results.

“I use Cubase on the Mac for live work, but the studio has always been PC-based. The one I’ve got at the moment is fully-loaded and was custom built. To get the same spec with a Mac would have cost me eight or nine grand!”

Never tempted to take one of the vintage toys out on tour with you?

“I’d love to take it all out with me, but it’s just not practical. And the digital emulations are so… well, if you blindfolded me and put me in front of a real CS-80 and the plugin, I don’t think I’d be able to tell the difference.

The strange thing about the real CS-80 is that it’s almost too rich and too powerful.

“The strange thing about the real CS-80 is that it’s almost too rich and too powerful. The sound is so massive that it’s difficult to find space to put it into a modern mix. I always have it going through a Tube-Tech multiband compressor, just to reign it in a bit.”

You’ve got an analogue desk, but you still like to mix in the box.

“Yeah, I’ve had this about six years. It’s Toft Audio and I bought it on the recommendation of James Murphy from LCD Soundsystem. The EQs and preamps are excellent and it wasn’t super-expensive. In effect, it’s become a sort of really big channel strip – it routes all the hardware into the computer. Send something like the 808 into it and start pushing the volume… it sounds amazing.”

Like the CS-80. Some people have mentioned that it can be difficult to get some of the vintage drum machines – like the 808 – to sit in a modern track.

“It depends. If I’m doing a remix and it’s a full-on pop project with a pristine sound, there’s no point in trying to use the 808 because there’s no room for it. But if you’re going for that raw, minimal, percussive, old Chicago house vibe, it’s perfect. Just the 606 and 808 slammed through a Culture Vulture.

“I guess that’s a lesson for us; you don’t need to fill every song with an infinite number of synths and pads and percussion. Listen back to those early house and techno tunes. You’ve got maybe four or five parts that have got the space to really punch through. You can engineer each part to work in harmony with everything else and build in real dynamics, without worrying that you’re going to upset the mix.

“I know it’s been said a million times, but it’s so easy these days to try and fix a song by adding more. But think about when you’re working with frequencies. If you’ve got an annoying notch on the bass, you don’t add more to drown out the notch; you just get rid of the bit that’s annoying you.”

Presumably, you’ve dabbled with other platforms apart from Cubase?

“Hot Chip albums always get taken to a bigger studio, which usually means moving everything over to Pro Tools. And Ableton looks interesting… very tempting. I’m sure there would be new creative avenues I could investigate with a different platform, but in terms of building songs, Cubase does everything I need it to do.

I’m sure there would be new creative avenues I could investigate with a different platform, but in terms of building songs, Cubase does everything I need it to do.

“And how long would shifting to a new platform take? Three months? That’s three months of learning instead of making music. Sorry, but I’m not one of those musicians; I’m not the super-tech guy who knows everything about everything. I’ve got no desire to learn how to programme for Max/MSP because it wouldn’t help me make music. And that’s all that matters, really. I’m sure we all know people who are constantly downloading new stuff and tinkering with the latest synths… and that’s all they ever seem to do. They can create the most amazing bass sounds and layer infinite kick drums, but they never actually finish a song.

“I’m almost the total opposite. I know enough to make music and that’s all I want to do.”

Joe Goddard’s new album, Electric Lines, is out now. You can find full details of Joe’s solo live dates on Facebook.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

“Excels at unique modulated timbres, atonal drones and microtonal sequences that reinvent themselves each time you dare to touch the synth”: Soma Laboratories Lyra-4 review

“A superb-sounding and well thought-out pro-end keyboard”: Roland V-Stage 88 & 76-note keyboards review