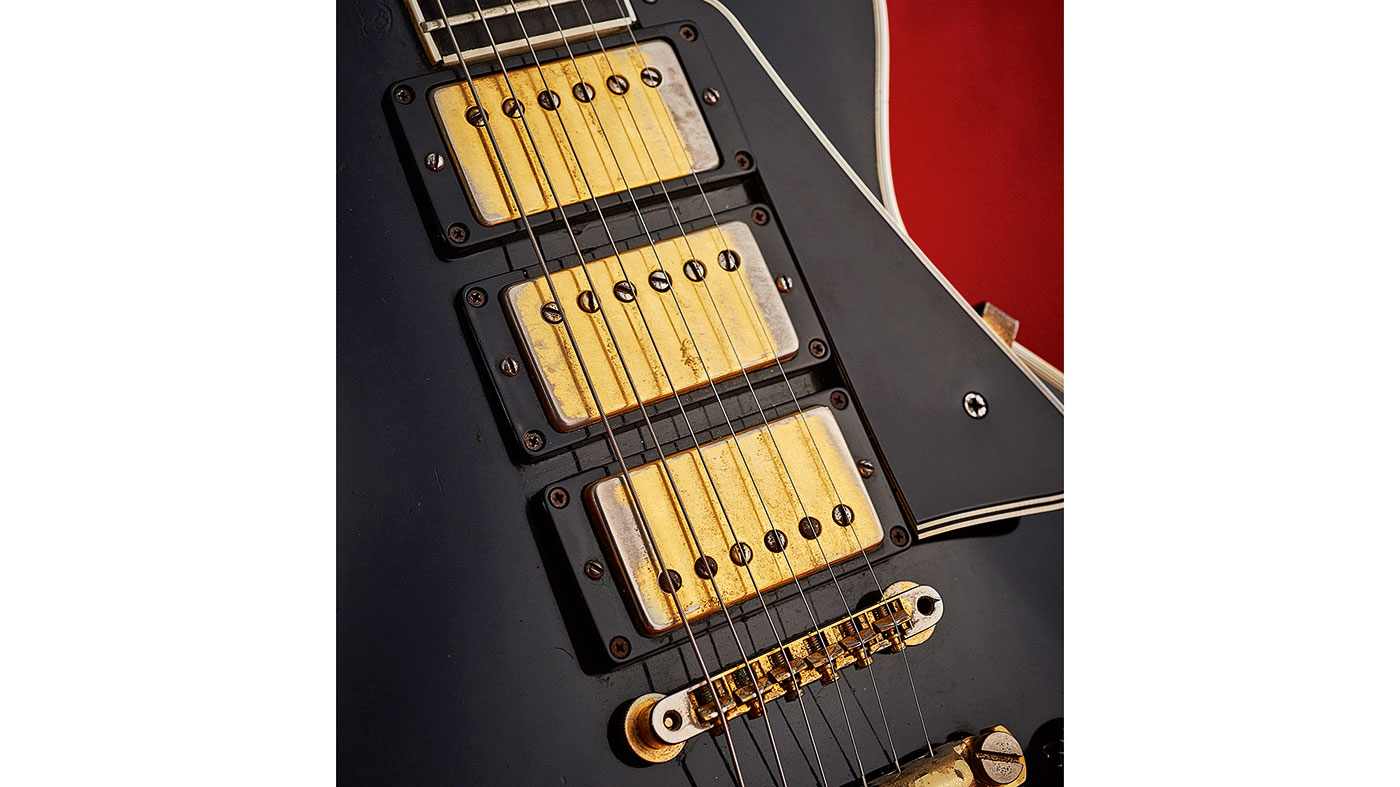

Historic hardware: 1958 Gibson Les Paul Custom

Up close with a vintage Black Beauty

Vintage guitar veteran David Davidson of Well Strung Guitars and the Songbirds vintage guitar museum retraces the history of the Les Paul Custom as we take a close look at this stunning 1958 Black Beauty…

David Davidson is no stranger to rare guitars. As the owner of Well Strung Guitars (formerly We Buy Guitars) in Plainview, New York, and COO and curator of the Songbirds vintage guitar museum in Chattanooga, Tennessee, he’s sourced vintage instruments for players and collectors for well over 40 years.

His expert eye remains focused on rarities from the scarce to the absolutely unique, yet to this day he retains a soft spot for those all‑time classics that piqued his interest in the beginning.

It always amazed me how guitar builders found their way through different problems with brilliant engineering and brilliant minds

“It was the Les Paul Custom that did it for me,” begins David. “I remember watching Bill Haley & His Comets’ Rock Around The Clock and the guitar player, Franny Beecher, was playing a Les Paul Custom. I thought that was just about the coolest thing I’d ever seen. I said to myself, ‘Wow! That is just beautiful.’ In that black and white film, it just bounced off the screen.

“I’ve opened up well over 10,000 guitars in my life,” David continues. “It’s a lot of fun and I still learn something new every day. You never stop learning. You’ve got to learn, and as an old hand, I love helping and teaching people about guitars. That’s what the [Songbirds] museum was all about in the first place. The educational aspect of guitars is very important to me and, at this stage in my career, it’s about teaching the next generation before all this stuff turns into firewood!”

Preserving vintage guitars themselves is as much to do with preserving our knowledge of them, and, in David’s case, his insight into what went on behind the veil at Gibson has always been rooted in a fascination with engineering.

“It always amazed me how guitar builders found their way through different problems with brilliant engineering and brilliant minds,” says David. “I was intrigued about why their guitars were made the way they were and how that changed over time.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Results may vary

Historically, the world’s most iconic guitar designs have always been - to varying degrees - works in progress, as manufacturers such as guitar giants Gibson and Fender sought to narrow the gap between the art of music making and the art of mass production.

“Leo Fender’s mantra was to be able to give everyone a tool to work with,” David reminds us

“He made a workman’s wrench of a guitar for people to go to work with, whereas Gibson was really looking for more of a dentist’s tool, or a fine craftsman’s instrument. The difference is that when Leo Fender made his first electric solidbody guitar, he mostly had it right straight off the bat.

“In fact, you can walk into your local music chain store and buy a reissue Fender Telecaster that was made more or less in the same way as it was originally nearly 70 years ago. There’s very little difference and that’s because they got it right out of the gate. But it took Gibson several years to develop their Les Paul guitars.

The Les Pauls were poorly planned. The [1952 debut Les Paul Model] trapeze tailpiece guitars were nothing short of a disaster as far as playability goes

“The Les Pauls were poorly planned. For example, the [1952 debut Les Paul Model] trapeze tailpiece guitars were nothing short of a disaster as far as playability goes, but that was something Les insisted on. It was obviously a big downfall to begin with, and it wasn’t until they used a wraparound tailpiece, then a stop tailpiece with [tuneo- matic] ABR-1 bridge, that the guitar was saved from an early extinction.”

Ultimately, it would take years for the Les Paul Custom to gain widespread appeal following its initial appearance in 1953. Prior to its release, the future was uncertain as Gibson tentatively began to test the water of the solidbody electric guitar market with its new designs.

“Gibson were very unsure whether to introduce the Custom or the [Les Paul] Junior first,” David tells us.

“They had both guitars in prototype, but in the end, it came down to dollars and cents. In other words, how much profit they could make on it. The Custom was solid mahogany and, as far as Gibson were concerned, not having to put a maple top on was a cost-cutting thing. They could paint them black and use virtually any piece of wood that didn’t pass the quality control for the body of a Les Paul Standard.

“It was the trimmings - the bells and whistles - that made it more expensive, although it was a bit of give and take. All that binding work took a tremendous amount of time and then there’s all that extra gold-plated hardware, but then they weren’t having to bond maple to the top of the guitar.

“Having said that, a lot of people didn’t think about the fact they weren’t getting a maple top. They just thought about a mahogany body - y’know: ‘If it’s mahogany, it’s good.’ But that produced a little bit of a darker, woodier tone; it didn’t spank as much as a maple top guitar.

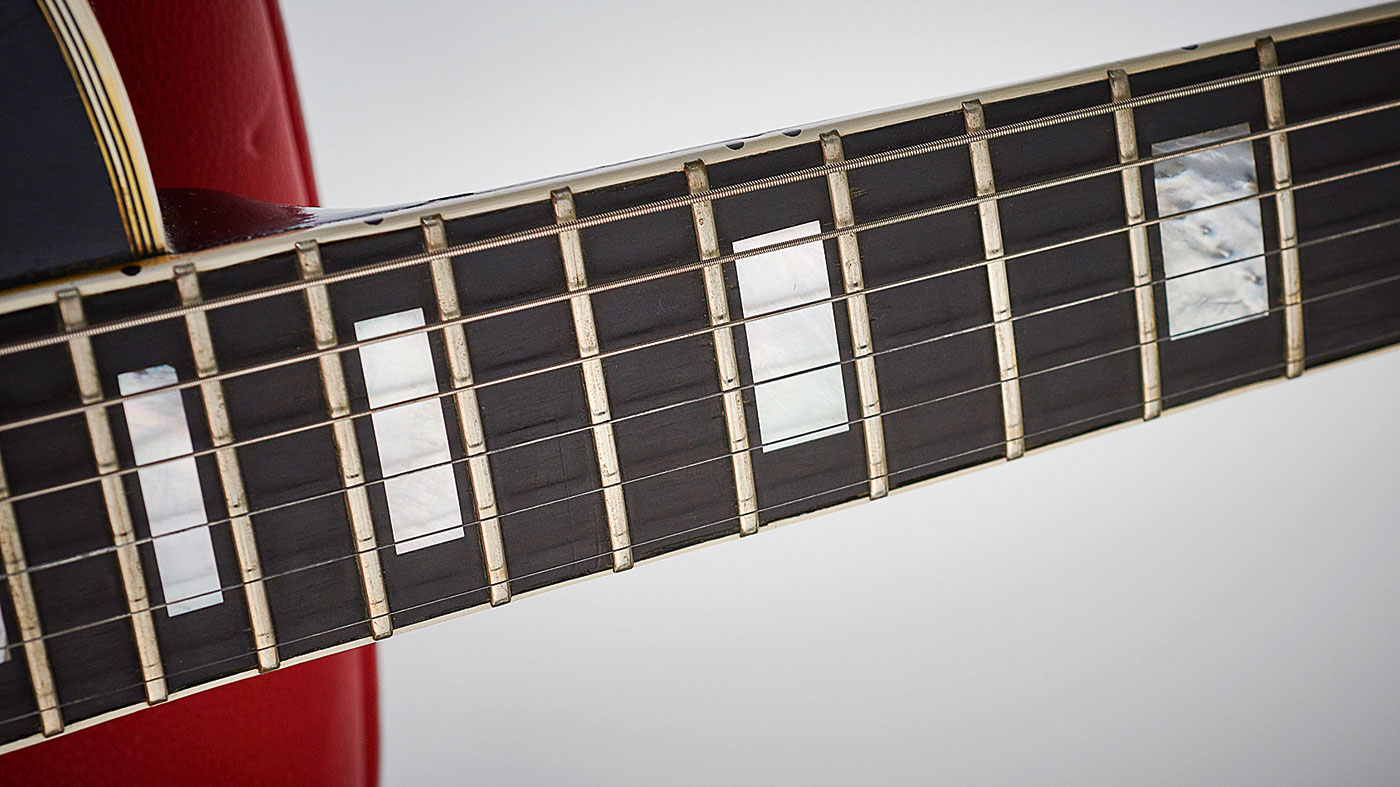

“I like the Les Paul Custom very much. I like the ebony [fretboard], the hardness of the wood and the way the sound refracts. Because of the way the sound refracts off the fingerboard, the notes kind of hop off, whereas when I’m playing a rosewood ’board the notes tend to roll off. With a Custom, the notes are really bouncing, especially when you’re playing with modern roundwound strings and larger frets. Customs can sound very snappy.”

Originally billed by Gibson as “The Fretless Wonder”, the Les Paul Custom unexpectedly found favour with rock ’n’ roll guitarists whose blues-style string-bending techniques were often assisted by using larger frets. As David recalls: “I’ve talked to old timers over the years who told me they used to go into Manny’s [Music in New York] to buy Les Paul Customs and they’d have them refretted the same day. They’d order them brand-new from Manny’s and get them refretted there before they’d even pick them up!

“These were rock ’n’ roll guys that were starting to experiment with different kinds of playing and they didn’t really like that big flatwound [string] sound and tiny little frets. Not everybody was looking for a fast‑playing neck. Some people needed and demanded different things from guitars and Les Paul Customs could provide some pretty interesting sounds when you could do things like bend strings by using lighter‑gauge roundwound strings, as opposed to the heavy gauge factory equipped flatwound strings.”

The Musical Big Bang

As popular musical styles radically altered in the creative explosion of the 1950s, rock ’n’ roll became a dominant force in the guitar world. Big changes were afoot as Fender continued to lead the solidbody market, and with Les Paul sales dwindling, Gibson found itself back at the drawing board once again in order to compete.

“Gibson were struggling in the mid‑50s, but Ted McCarty and Seth Lover’s humbuckers saved the company,” explains David. “The PAF humbucker changed the guitar world forever. When I met Seth Lover, he told me he was experimenting and had many different pickups laying on a bench plugged in. Magnetically, one stuck to another and he noticed the hum went away. He said he ignored it at first - that it didn’t mean anything. But I guess he just didn’t sleep on his discovery very well!

To me, it’s a musical big bang theory. Gibson hit the home run with the PAF. No doubt, the whole idea that you could reduce hum was important

“To me, it’s a musical big bang theory. Gibson hit the home run with the PAF. No doubt, the whole idea that you could reduce hum was important. It was an amazing revelation at the time. Remember the first time you saw high‑definition TV? That’s kind of what it felt like. There was nothing like that before. It was helpful for getting rid of 60‑cycle hum, but it also meant you could turn the amp up louder.”

In tackling the practical issue of 50/60‑ cycle hum, Seth Lover had inadvertently rewritten the rulebook for guitarists, particularly with respect to those rock ’n’ roll and electric blues players for whom volume, crunch and sustain had now become an integral part of their sound.

“It changed guitar music forever,” says David. “It’s funny; a lot things perceived as improvements were a happy accident. Things don’t always end up being used as they were intended. I mean, there are plenty of men taking Viagra, right? [Pfizer] were trying to find a heart medication when they discovered the ‘side effect’ and later decided to market it in another direction. Quite often those kinds of happy accidents are the mother of invention.”

While the PAF became Gibson’s saving grace, at the time, many other ideas either failed to hit the mark or remained under wraps at the factory.

“In 1957, just before they were converting over to PAFs, some Customs came through with two P‑90s, as opposed to one P‑90 in the bridge and an Alnico 5 in the neck,” reveals David.

“As a matter of fact, I have a prototype in the museum that has a chambered body. It feels good, but it wasn’t a hit with the representatives of the factory because of the amount it cost to chamber it and the fact that, tonally, it changed the sound of the guitar - it lost a lot of bottom‑end and was very midrange‑y.

“I also have three double‑PAF Les Paul Customs, without the middle pickup, from ’59 and they’re all pretty good‑sounding guitars, too. I’ve always really loved the sound of the centre pickup selection on a triple PAF guitar with the bridge and centre pickups working together, but the middle pickup was often an inconvenience for a lot of players, especially rock ’n’ rollers.

“For the jazz guys who picked lightly, it was often no problem to manoeuvre around, but I think for the rockers it was different. Peter Frampton said he took the cover off the centre pickup first because he hated the way it sounded when his pick would hit it. That was the first cover he took off, and he liked the look, so he took them all off.”

People started contacting each other about Les Pauls and they suddenly started becoming the guitar to have

Despite the PAF humbucker’s virtues, however, it seemed that no matter how hard the company tried to get its Les Pauls off the ground, Gibson still couldn’t get them to fly. By 1961, in a last-ditch attempt, the entire range was overhauled into a profoundly new SG-style body shape, after which a disgruntled Les Paul saw his name removed from both headstock and model designation. It appeared as if all might be lost, until a small circle of cutting-edge guitarists started bringing single-cut Les Pauls along with them into the limelight.

“Keith Richards played a [1959] Les Paul [Standard] on TV in 1964 on the shows Ready Steady Go! and The Ed Sullivan Show,” remembers David, “and by the time he had gotten back from the studio to his hotel, he’d received a message from Eric Clapton asking him about the guitar. Jeff Beck had also shown an interest, and that was just the beginning of it.

“People started contacting each other about Les Pauls and they suddenly started becoming the guitar to have. At that time, the price point was still very shallow: back then, you could get a ’Burst for $700 to $800. It was like that until the mid-70s when prices started to pop. I’ve got pictures from my old shop, We Buy Guitars, where there’s a whole row of them. You could have had any one you wanted for $1,200.

“Les Paul Customs don’t sell for the same number as the Standards and, honestly, for more than any other reason, it’s because of the top. People like the way ’Bursts age and fade. That and the fact [Customs are] black and when they get beat up they just don’t look so pretty any more. There just aren’t enough props given to the Les Paul Custom. I like them and I’ve always had one in my collection. The first one I got - a ’57 - cost me $350 in about 1981, and I’ve owned that guitar four separate times now!

“Maybe I should have kept every guitar I ever bought,” muses David as we finish up. “I wouldn’t have any money, but I’d have some great guitars!”

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.

“To be honest, I feel like I am playing a high-end Gibson guitar”: Epiphone and Guitar Center team up for a colourful riff on a cult classic with the limited edition run Les Paul Custom Widow

“The humbuckers give it so much power and such a wide variety of tones while the destruct button really sets it apart from just about any other Tele”: Fender unveils the Mike Campbell “Red Dog” Telecaster