Herbie Flowers on working with Lou Reed, Bowie and his 1960 Jazz Bass

The legendary session bassist talks

If you’ve ever listened to a hit record from the 1960s or 70s you’ve probably heard one of Herbie Flowers’ iconic basslines.

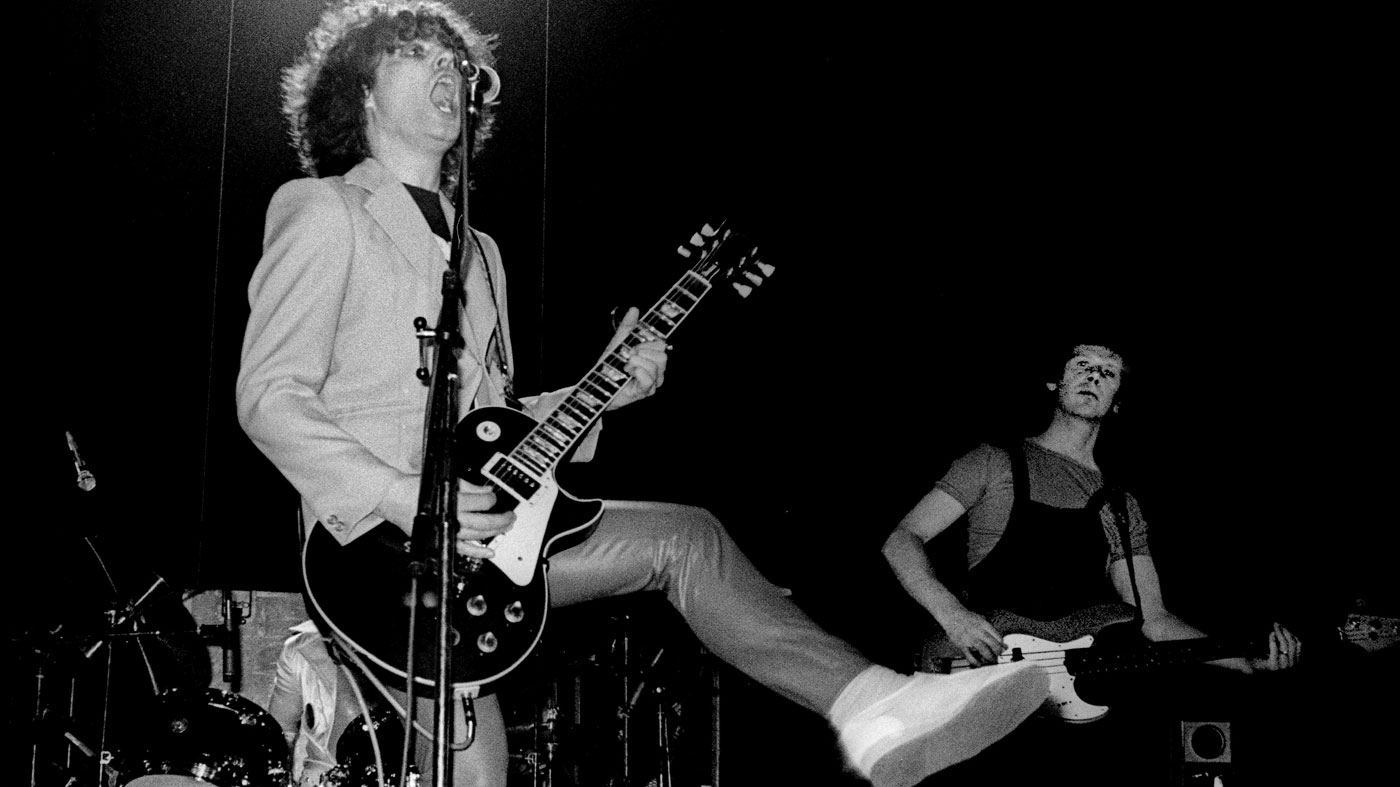

In his long career as a session musician, he has worked with David Bowie (Space Oddity, Rebel Rebel), Lou Reed (Walk On The Wild Side, Perfect Day), Paul McCartney (The Long And Winding Road), Marc Bolan [pictured with Herbie above] and a host of other stars. Flowers gave a talk at Basschat’s South East Bash in September 2016, and we took the opportunity to interview him.

After seeing him appear onstage with his double bass and what was clearly a vintage bass guitar, we had to know what they were. The double bass is a ‘Professor’ flatback from Hawkes & Son, and the guitar is a 1960 Fender Electro Blue Jazz, both bought new back in the day.

I just love the sound of the bass, it’s my first love

Somewhat surprisingly, Flowers has used just those two instruments, with no backup, for the whole of his professional life, spanning over 50 years. They have defined his sound: has he ever felt tempted to become endorsed by manufacturers? “No, they’ve never got in touch,” he chuckles. “I don’t see myself as a big name. I’m not a great lover of rock music. I’m a jazz lover.”

We notice that his Jazz bass has a fuzz switch - what does it actually do? “There used to be a battery in it, and when you threw the switch, it made those two connections get near each other and a spark jump across. But it didn’t work! It made such an ugly sound I took it out and lost it.

“I don’t like effects on basses: I like just that raw sound, like James Jamerson and Paul Chambers. When I was a kid, my father gave me a pair of earphones to try: I discovered that if I pressed the earphones to my head, I could hear the bass! And I just love the sound of the bass, it’s my first love.”

Flowers’ sound is defined not just by his bass but also by the strings he uses - and of course by his fingers.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I’ve only ever used Rotosound black nylon-wound Tru Bass strings: that set has been on there six years, and I like them because there’s no squeak and I’m no good at slapping. I think it’s good to play with a pick, as well as with your fingers. If you’re booked for a recording studio session, the producer will choose you for the sound that you get and the style you play in.

“They’ll ask who’s playing on a certain record, and the reply might be 'his name is Herbie Flowers.' That’s how you get work, by having a distinctive sound and a certain kind of outlook. Speaking of which, I wish there were more female bass players in the business. Those I know are much better than the blokes, going all the way back to Carol Kaye and, more recently, Esperanza Spalding - great bass players.”

Given the calibre of the artists Flowers has worked with in the studio, has he ever felt in awe of any of them?

“No, because you’re hidden from them most of the time. I did a month at the Cambridge Theatre for Eartha Kitt, Shirley Bassey and Dusty Springfield, but I wasn’t intimidated by them. You can’t sit there gawping: you’re actually there to be as courteous and reliable and unobtrusive as your playing must be. It’s sad that today music is made by machines, because there’s less work for musicians like us.

I don’t see the point of setting the record straight on exactly what I played on, and when. I’m not interested in the cult of personality

“In the 1960s we session musicians were running round in circles, rushing to get from Olympic in Barnes to Wessex in East London, and the session in Barnes could have been for Bowie’s Diamond Dogs and the session over the other side could have been for one of those American bands that came over… and you were never late. I don’t know how we did it.”

However, only a small percentage of the work Flowers has done has been in the studio. “The rest is nightclubs, West End shows and nightclubs like Danny La Rue’s and the Raymond Revuebar, and then getting up in the morning and going on parade [playing the tuba] because I was in the Royal Air Force, marching up and down.

“I’ve always been in a band, that’s why I can’t write songs by myself: I have to be in a unit, so I’m not so much intimidated by being booked as an individual. As it were, you build up a fanbase of famous people. It’s the other way round as well: I build up a fanbase of people I like working for.”

Unpredictable success

Inevitably, at times the session musician and the band are clearly mismatched, and Flowers has had his share of frustration. “I walked out on a client when they said to me: 'On Space Oddity, what you’re playing seems to bear no relation to the song whatsoever. Can you try and put that kind of feel on our song?' And I was stumped. I don’t get a buzz out of rolling in the studio and wearing a pair of earphones with a cowbell and an electronic drumkit in my ear.”

Flowers played bass on some songs that went on to become massive hits. In the studio, before release, did he predict their success? “Musicians always think they’re playing on a hit. The only time I was right, was in the pit when ABBA did Waterloo at the Brighton Dome. Their guest conductor walked down the aisle dressed as Napoleon, and we decided the song would be a hit.”

That was the Eurovision final? “I think so… but I didn’t keep my diaries, and I’m glad I didn’t, because every time I’m asked if I played on a certain record or show, I simply say, why do you need to know that? I don’t see the point of setting the record straight on exactly what I played on, and when. I’m not interested in the cult of personality.”

Throughout our conversation, Flowers repeatedly points out that he’s simply doing his job, which implies a certain degree of detachment from his studio work.

Lou Reed’s ‘Walk On The Wild Side’ - I only played [the bassline] once

“Take Lou Reed’s ‘Walk On The Wild Side’ - I only played it once, and Lou said to me, years later: ‘It’s because of you that I spent 20 years trying to shake that out of my mind’. It changes the whole dynamic of his audience.”

That said, there is something that Flowers has done in his entire career that’s very special for him. “I did two albums, one from 40 years ago, called The English Jazz Quartet, which was basically a band called Back Door with Ron Aspery, Steve Gray, Tony Hicks on drums and myself, and one called A Jazz Breakfast, with Mark Edwards, a pianist, and Malcolm Mortimore. They are the only two times in my career that I felt my feet leave the ground. You can request them by email at my website.”

Flowers’ site also lists his community work - charity fundraising, work with Brighton-based the New Note Orchestra, comprising people in recovery and pro musicians who want to help, and even a seriously large choir.

“It’s the Shoreham Singers By Sea. By accident, I said on a gig, ‘How many of you would join a choir if we put one together?’ And 150 people put their hands up! You know, I have to create my own work, because it’s part of my beliefs that every penny you earn, you’ve got to earn it for someone else. I mean that. Money’s being taken out of everybody’s pockets and we’re watching ’em do it.

“I pity young people at home wondering how the hell to crack it in the music business. I wish I could do more for the young musician. You know, I wish a lot of the people who make a lot of money out of music would give some of it back - in the form of time and money, to set things up such as music colleges and facilities. We need more of those.”

“I really thought I was going to die... and it absolutely was so freeing”: Blink 182’s Mark Hoppus talks surviving cancer and his band’s resurrection

"I remember showing up at 10 or 11 in the morning and working on solos and that leading to two or three o’clock in the morning the next day”: How Metallica beat the clock and battled fatigue to create a poignant and pulverising anti-war epic