Helado Negro on working with the SAL-MAR Construction, a one-of-a-kind analogue synth and “self-generating compositional machine” from 1969: “This wasn’t parallel to developments from Moog and ARP… this was so much in its own world”

Roberto Carlos Lange’s acclaimed latest album took him on a synth quest across the US. But it was back at home, piecing it all together in Ableton, that the rich tapestry took shape

When you think of an album which centres synthesis, electronics and its makers as a core theme, you probably conjure a sonic image of aloof, difficult music, summoned by an automaton humanoid in a natty silver jacket.

But rarely do you find an album where those references are so dextrously integrated into commentary about human existence as they are on Phasor, the ninth LP by acclaimed American producer-songwriter Roberto Carlos Lange, aka Helado Negro. And the work has earned critical acclaim aplenty to show for it.

We caught up with the busy artist – at the time midway through a tour – and found out more about the sprawling history behind this impressive record.

Frankenstein's synth

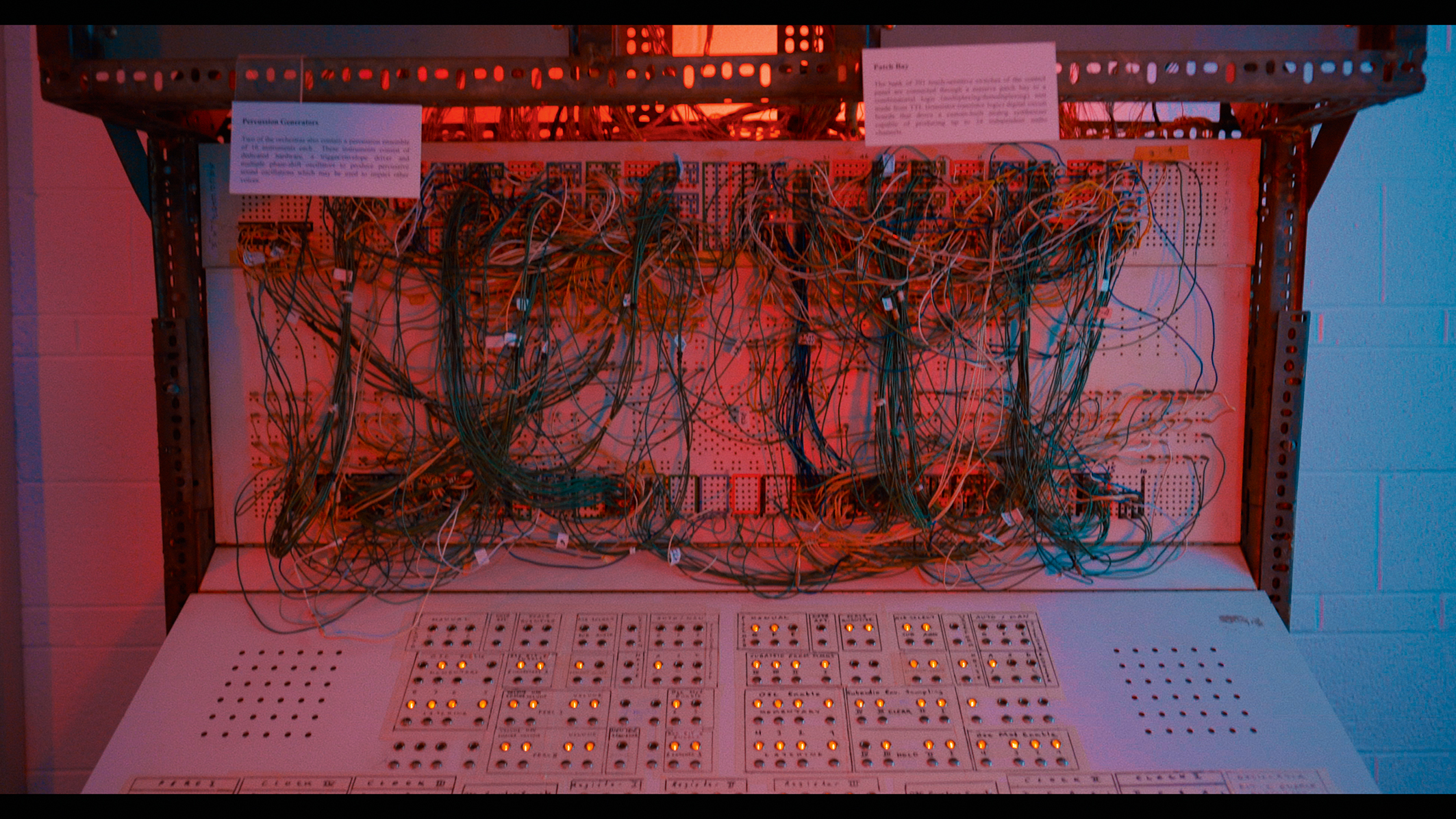

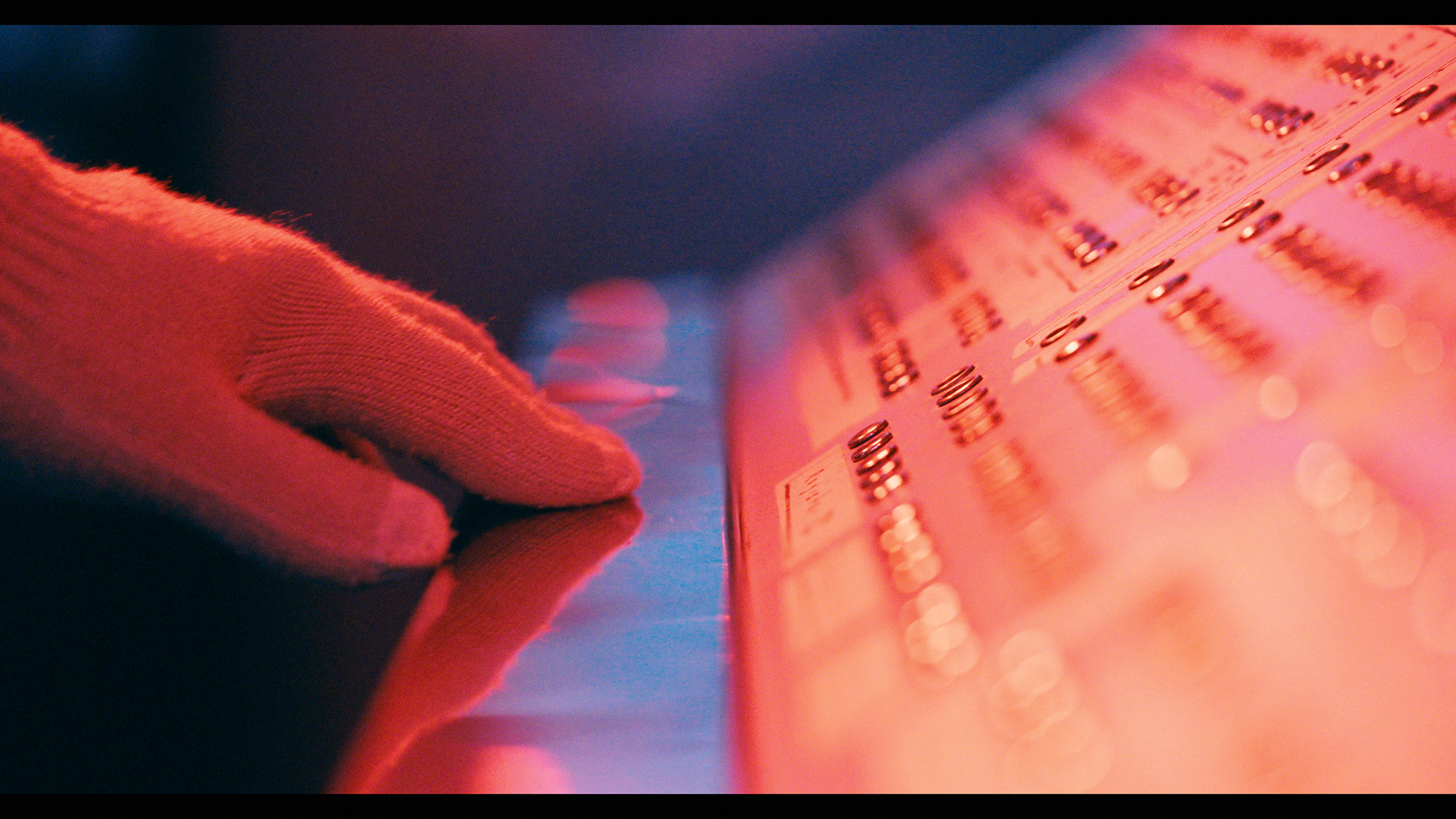

At the heart of Phasor is a brick shithouse of a synth. The contraption in question, the Sal-Mar Construction, holds pride of place at the University of Illinois, and is a Frankenstein of sorts, forged in 1969 from parts of an ageing super-computer by its ‘father’ Salvatore Martirano. With 291 touch-sensitive switches, and sound output through a network of 24 satellite loudspeakers and four main speakers, its face is tattooed with handwritten scribbles where the usual labels go, below a spaghetti-like tangle of cables.

But look closer and its genesis was less like the big-buck, circuitry-first visions of more famous pioneers, and more familiar to the thought process of some of the more reflective creators and developers you’ll read about on MusicRadar today. Lange takes a stab at explaining Martirano’s proposition: “He was like, ‘oh, I have an idea to make this really weird machine that makes sounds. It’s going to be a self-generating compositional machine controlling analogue oscillators with this digital supercomputer brain’. And then somebody said yes, and they built it.“

“Obviously that kind of thing is really common now. But I think it was just so brilliant that it was actually done, and it was thought of and it was supported, and that he was able to create this very unique instrument to perform with and to record with. So there’s that essence and that history of it.”

Corresponding with the archivist who takes care of the Sal-Mar from 2015 to 2019, Lange finally arranged to visit it. “And then when I did,” he explains, “it was such an enlightening experience. It is a one-of-a-kind synthesiser.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

How was his experience, after so much buildup and such a long journey across the US to see it, of actually using the instrument? Not to mention given that he only had one day to master what looks like an incredibly complex workflow! “So the archivist has a good understanding of getting you going and getting you started and getting you restarted,” Lange explains. “If things get messed up and then you’re on your own and then you’re like, ‘I have no idea what I’m doing’.

“You can read the words and understand what those words mean on the panels, meaning like clock or sequence or oscillation or whatever dividers, stuff like that. I’m like, ‘oh, I guess this does this’. But it was like walking in the dark and slivers of light would pop in and you’d be like, ‘okay, I’m going to keep going this way’. That was exciting as there’s no expectation, and everything was a surprise.”

When asked if it lived up to his expectations, Lange said: “When I was recording with it, it was just so disorienting because it’s so idiosyncratic to someone’s process and work style. This wasn’t parallel to developments from the likes of Moog and ARP and people or companies like that making these synths that were more commercial; more for studios or more for musicians, specifically, to create musical formats or themes or ideas that were already kind of existing. But this was just, like, so much in its own world. So falling into someone’s process like that was really fun.”

Job done, you might think: historic synth, rich backstory, concept album in the bag. But it was not as simple as that, explains Lange. The initial joy at the sounds he produced during his day with the Sal-Mar soon, became complicated as he contemplated how to ultimately do them justice on record.

“I was kind of a little headstrong about what I wanted to do with them. I was being very special with them and protective of them. I was like, ‘no, they have to exist in some kind of very specific format of creation’ or whatever, something that was like… It was starting to become more about the idea than it was about the sounds. And I was kind of removing the intention. And so then I said, let’s just use these sounds. I had some song ideas, and I started inserting some of the Sal-Mar idea sounds in there. It was inspiring, for sure. And whether you hear it a lot or you hear it not at all, it’s still part of the process.”

Lange meets Oliveros

It was in that lull period that a coinciding thread of inspiration – along those lines of celebrating the faces behind the musical machinery – formed, albeit unwittingly. The first track on the album is entitled LFO (Lupe Finds Oliveros); the parentheses are useful, given that, even with the help of Google Translate, the Spanish-language lyrics aren’t going to hand you the meaning of this sunny, psychedelic, icicle-defroster of a song on a plate, but nonetheless, it’s worth the deep dive. “I always try to think of the best way to describe this without taking up too much time,” laughs Lange.

This idea of deep listening, but just the work itself. I thought that was really beautiful here

We start with Oliveros: that is Pauline Oliveros, founding member of the San Francisco Tape Music Center in the 1960s and a pioneering experimentalist whose legacy is only just beginning to be unveiled. “Pauline is obviously somebody who a lot of people know. Her work as an educator, as a musician, as a philosopher, and her practice in deep listening, which is like this philosophy of connecting with yourself and the world through listening to it, listening with your ears, but also with your mind and connecting.

“Not necessarily like listening to music, but kind of like hearing what the world feels like and sounds like. And I didn’t really come to understand or learn a lot about Pauline’s work until I really got into it over the past few years. It was in my peripheral world, seeing or hearing her name, some tracks here and there. Something just resonated with me. This idea of deep listening, but just the work itself. I thought that was really beautiful.”

Lange meets Lupe

And then (“on one of these deep, nerdy nights of me looking for this Fender Vibrachamp amplifier, kind of just doing this whole 55 tabs open thing”) Lupe Lopez came into the inspiration mix.

“I stumbled upon this little mini forum that had this black and white photo of her sitting at a bench at the Fender manufacturing shop. And it says in the caption that she was building Fender Champs. And it was really striking to me in a lot of respects. There was a mystery to it immediately.

So in a music world, you just go and get something and you start making something. There’s no real connection to the people who put their hands inside those parts

“I think what clicked was sometimes you don’t think about the people who are making the things that you’re using as a musician, but also as a human in general. There’s such a disconnection to that part of the process of what you’re doing. So in a music world, you just go and get something and you start making something. There’s no real connection to the people who put their hands inside those parts.”

Lange started to learn about the following and market for these Lupe-built amps; it turned out he wasn’t the only person drawn to this mysterious figure. “On the inside, there’s an inscription on a piece of masking tape that says ‘Lupe’. And I’m guessing they did that for quality control, to kind of help keep track of who was doing what. From what I gather, it’s like, through her care and talent and touch, she was able to harness a specific sound that wasn’t [there].

“I’m sure there were a few other amp builders there using the same design, same component, same stutter, same everything. But something she did with the amps that she made really seemed to resonate with people a lot.

“I don’t think anyone’s ever thinking about the things that they’re doing when they’re making things just out of necessity, as we’re all trying to work and pay bills. I’m sure she was in the same boat. She was like, ‘oh, I got this job. It’s stable, and I’m making amps’. I’m sure she wasn’t thinking, like, ‘my legacy of building these amps, it’s going to be long’. And I love that. I love that there’s just, like, a care that went into that.

Best guitar amps 2024: Our pick of combos, heads and pedalboard amps for all budgets and abilities

“I think there are kind of these three points that I was referencing, this idea of how her intention and talent and care resonated over time, that it affected these people who were listening to these amps over time and using these amps that were getting inspired by the tone and the way to use them kind of touched back to this idea of deep listening. They were listening, and they could hear this feeling of what she was doing, and she was listening to herself by creating these in a very specific way. And I thought that was kind of like the big loop around with Lupe and Pauline and these people.”

Lee “Scratch” Perry and sine-wave poetry

Putting all of it together, the album title refers to “a numerical vector for oscillation in physics and engineering”. The backstory for that choice is reassuringly down to earth: “I remember there was like some Lee “Scratch” Perry video and I was watching him use a Mu-Tron Phasor that’s spelled with an ‘or’ (as opposed to ‘er’). And I was like, dope! [Laughs]”

The word got stuck in his head in a way that will be familiar to any of us who’ve stared at a Word doc for that bit too long. “I was like, what does phas-or actually mean? And then when I was looking up phas-or, I came to understand that the definition was a way to measure when two sine waves are essentially intersecting and understanding at what points they intersect in terms of either amplitude or frequency.

“I found it to be kind of poetic. I like this idea of a unit of measurement when things intersect. And I kind of thought about humans and people and our day-to-day of how we measure ourselves. When was the last time you hung out with your mom or your best friend? What was that like? And it’s kind of like we overlap and come in phase and out of phase with these things. And there’s just ways that we experience life. I really enjoyed taking that away.”

Everything going upwards: using software

Being as plugged into the analogue world as he is, you might think that Lange might be a card-carrying member of the computer-avoiding pack, but coming from a computer arts and animation background in his early career, the picture is not so straightforward.

He is a long-time Pro Tools user since getting a free copy in (“I think”) Future Music magazine in 1997. “Version 2.2, or something like that. It was like a four track recorder, and it had like a MIDI track as well. I made my first beats using that.”

Then came a cracked copy of Ableton Live at college, and like many, considered it a game-changer for the storytelling it could do. “The plugins were so amazing. They were just so different and distinct from the stuff you could get in Pro Tools. I would use the things that friends would build, but use SuperCollider or like Max MSP as ways to process. And then Reaktor was kind of a big one.

When people ask me, ‘what’s your instrument?’, I’m like, I play whatever I can to make what I can

“I would use Reaktor with my MPC and kind of build a lot of synths and control it via MIDI. And that was a huge part of my life, and it still is. If anything, I compose and create music with computers. When people ask me, ‘what’s your instrument?’, I’m like, I play whatever I can to make what I can, but when I make my music, at the end of the day, however I get there, it ends up on the computer, and I’m creating and building and structuring it like that.”

He continues: “I think that for a lot of people, or at least people who compose on computers, it’s like you’re building vertically, you’re building in time that’s in place, as opposed to a lot of singer-songwriters, who build in a linear sense. They’re like verse, chorus, here it comes. But when you’re thinking about music that’s composed on a computer, everything is just going upwards, and then you’re peeling back the layers and then restructuring them over time, but not necessarily moving through time in respect to telling a story. That’s the way I look at it.”

Helado Negro's Phasor is out now on 4AD.