Heaven 17's Martyn Ware: "Kraftwerk were only brilliant because they were rich!"

At the forefront of music technology for 40 years, Heaven 17 love their analogue synths. Martyn Ware tells us more…

“Everybody goes on about how brilliant Kraftwerk were. Yes, but they were only brilliant because they were rich!”

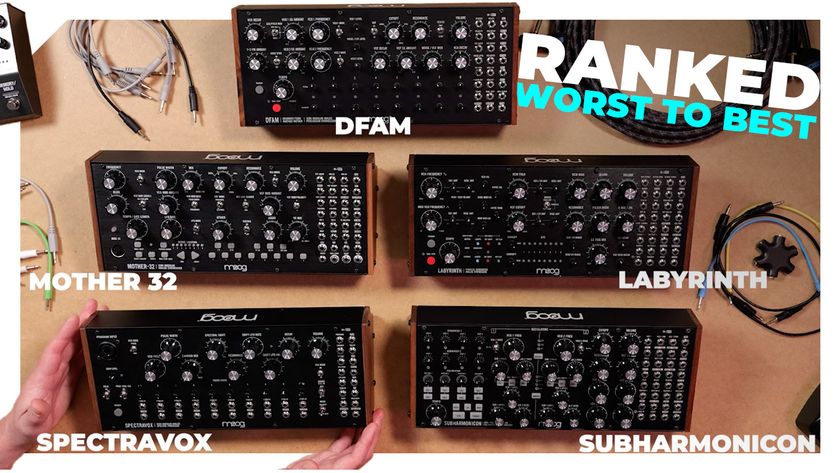

Although Martyn Ware allows himself a mischievous chuckle, he is trying to make a serious point. “If you’ve got a studio that’s wall-to-wall synths and Bob Moog is custom-building stuff for you… yes, you still need a good idea, but the chances of you turning that idea into a great album have been greatly increased.

“When I was a teenager, living in a two-up-two-down in Sheffield, with an outside toilet, my chances of owning a Moog [the cost of the original Moog Modular system ran into tens of thousands of dollars] were zero. Less than zero. Wasn’t going to happen.

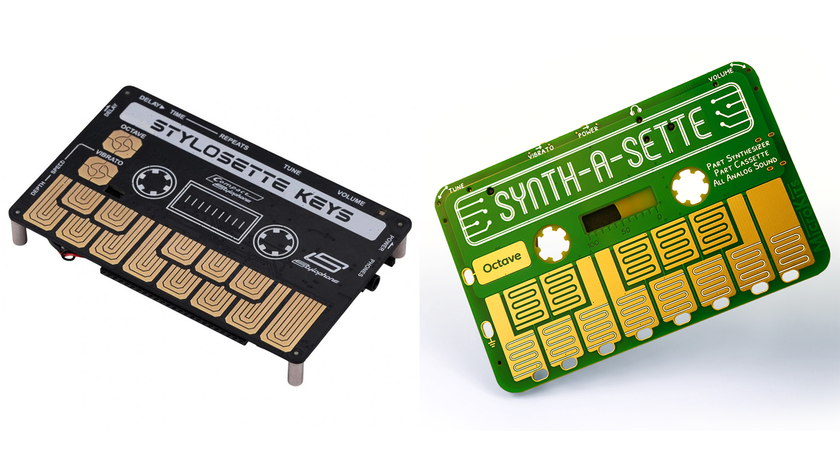

“But companies like Roland and Korg could see where things were headed. By producing synths like the MiniKorg-700 and Roland SH-1000, they gave electronic music to the masses. For the first time, they were available to Average Joes like me. The Korg-700 changed my life!”

As a founder member of the Human League, Ware – along with vocalist, Phil Oakey, and fellow techy, Ian Craig Marsh – played a major role in the history of electronic music in the UK. Their debut single, Being Boiled, was released in June 1978, almost a year before Gary Numan’s Are ‘Friends’ Electric? The band signed to Virgin in 1979, but by the following year, Ware and Craig Marsh had already moved on to Heaven 17, with new vocalist Glenn Gregory.

Although it was that early-'80s period that gave Heaven 17 hit singles like Temptation and Let Me Go, they have been steadily recording and touring for almost 40 years – without Craig Marsh, who left in 2007. And when Ware is not in the studio or on the tour bus, he’s a regular speaker on the music tech circuit, a visiting Professor in Media and Arts Technology at Queen Mary University of London, a Red Bull Music Academy lecturer and co-founder of 3D sound tech company, Illustrious.

As a man who describes his fascination with music technology as ‘verging on the pathological’, he admits that he’s looking forward to having a chat with Computer Music.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“This should be an interesting couple of hours. Let’s see where we end up!”

What got you interested in synthesisers and electronic music?

“Prog rock, really. Emerson, Lake and Palmer. I had two sisters who were quite a bit older than me, so the house was full of records. At first, I listened to Motown, but by 15, I’d moved on to rock. ELP, Deep Purple, King Crimson.

“I remember going to see Emerson, Lake and Palmer at Sheffield City Hall… Keith Emerson surrounded by his mountain of keyboards. You’ve got to remember that this was not long after Apollo 11. We were living in an age of optimism and futuristic engineering. The synthesiser made a noise that seemed to echo those times. The only problem was that people like me had no access to them.

“Then we had Roxy Music, Bowie, the krautrock bands like Can and Neu!. And Kraftwerk. There was interesting stuff coming out of America… Suicide, the New York Dolls, Iggy Pop. And disco, of course. Giorgio Moroder. That probably sounds like a right old hodgepodge of styles. Yes, it was. But that hodgepodge was the inspiration behind the Human League, Heaven 17 and just about every other musical project I’ve ever been involved in.”

We’re still way ahead of the BBC Micro and ZX Spectrum, here, but you did have some experience of working with computers.

“Yeah, one of the first jobs I got after leaving school was a computer operator. I wasn’t a programmer. My job was to input all the info on punch cards. The first computer I worked on was a 16K machine that was the size of a small shed. I then moved on to an IBM 3600, which used to process the payroll… lots of admin jobs.

“Bizarrely, my mate Ian [Craig Marsh] had a similar job and we both did a lot of night shifts. It was great. Once you’d got the program running, there was nothing else to do for the next seven hours. All of that time was spent writing lyrics and coming up with song ideas.

“There was one other important stage in the development of the band: an interview Brian Eno did with the NME. The basic thrust of his argument was that rock ’n’ roll was dead, and all you needed to make music was a synth, a mic and a tape machine. Me, Ian and Phil all read that interview, and we all believed him.”

He wasn’t far off the mark!

“It wasn’t easy predicting the death of rock music in 1970s Sheffield. Like Birmingham, it’d always been a ‘rock city’. Long hair, leather jackets and all that. We fancied ourselves as musical mavericks. Outsiders. We had no interest in being signed or releasing a record. All we wanted to do was experiment. Messing about in a scruffy old office space that we rented as a rehearsal room.”

But you did release a record. Being Boiled. What was it made with… what did the Human League studio consist of?

“My Korg-700, Ian’s System 100, an SM58 mic and a Sony two-track tape machine that, luckily, had bounce facility. No computer, no midi, no sync of any kind. The only sequencing we had was the System 100, so all the basic rhythms came from that, and everything else worked around it. Everything was played live and bounced down to make room for the next bit of music.

“We had a lot of grand ideas for that song, but we soon realised that there were built-in limitations because you could only bounce-down four or five times before you began to lose quality. People always talk about the ‘wonderful minimalism’ of Being Boiled, but that wasn’t anything that came from us. It was simply because the equipment didn’t allow us to add anything else.

“After we signed to Virgin, we did another version where we added loads and loads of other synths. That was how we’d always imagined it would sound. Let’s put as much in there as we can. But – and I think this is a really important point – even today, people still come up to me and say that they prefer the original version. That was an early lesson for us.”

Adding loads of extra stuff does not necessarily make a song any better.

“Precisely. It’s something I often talk about when I’m lecturing. The sheer volume of stuff that we can use in the studio. This idea of option paralysis. You have so much choice that you can’t actually make a choice. It’s quite interesting, because most of the students I teach have never known any different. Their entire experience of making music has been with unlimited synths and drum sounds. So… I set them a challenge. Write a piece of music using one synth and one drum module.

“Some get it, some don’t. Some people get worried about their lack of choice. As if that will hinder their imagination. If you analyse how you work in the studio, you usually find it’s the other way around. Count all the synths on your computer. How many of them do you use?

“It’s something we’ve all been guilty of. We did it with Heaven 17 when we first started using samplers… around the time of The Luxury Gap album. Days wasted in the futile pursuit of the ‘perfect’ sound. And we were in Air Studios, paying God knows how much. Even if you’re using nothing more than the basic Logic or Cubase package, you’ve got plenty to choose from and you need to develop an inner confidence in your choice of sounds. That’s the kick drum I’m going to use. Job done. Move on.”

Even if you’re using nothing more than the basic Logic or Cubase package, you’ve got plenty to choose from and you need to develop an inner confidence in your choice of sounds.

At what point did computers find their way into the studio?

“Very early. We were working with the BBC Micro and the Osborne Personal Computer – remember them? But it was the Mac that really made the difference. We had one of the first hundred Macs that came to the UK, using Performer, which was the only platform available for Macs at the time. Bit by bit, we were moving away from the old hardware system… a Roland MC-8. All of the sequencing could be off-loaded to the computer.

“It was a wonderful time to be making electronic music because technology was changing so fast. Every couple of months, there was something new to try. And it felt as if it was the musicians and producers who were actually fuelling these developments. We were putting the cart before the horse. Wouldn’t it be great if we could do such-and-such in the studio. Next thing you know, somebody’s developed a piece of kit or software that allows you to do it.

“This was the first time in musical history that something like that had ever happened. The democratisation… the emancipation of the means of musical production.”

Ironically, that trend did get reversed in the early days of DAWs. It all became a bit professional. And very expensive.

“Quite snobbish, as well. Suddenly, you had all these producers saying, ‘Pro Tools sounds so much better than any other platform’. As far as I was concerned, that was a load of bollocks. Technically, I remember being shown the evidence that Pro Tools had the edge, but I never heard the difference.

“It’s the same with UAD today. The numbers tell you that it’s better, but… personally, I think it’s a lot of tosh spouted by people who want to make out they’ve got a superior rig.”

Suddenly, you had all these producers saying, ‘Pro Tools sounds so much better than any other platform’. As far as I was concerned, that was a load of bollocks.

What’s on the Heaven 17 rig?

“It’s a completely maxed-out Mac, with virtually every softsynth you could name. Everything from Arturia and Roland. Spectrasonics. Libraries from Spitfire Audio. Native Instruments. Kontakt is my sampler and it’s become one of the main tools I use when I’m working on sound installation projects for my company, Illustrious. I can pretty much create any sound I want. Well, 95% of sounds!

“If I’m being totally honest, that’s where my passion lies: sound design. Even though I’m in a band and I compose music, I consider myself more of a sound designer. If you look back at the early Human League albums, I think you can see evidence of that. Running parallel to the idea of writing a pop song, there was the desire to experiment.

“There’s a track on the first Human League album called The Dignity of Labour, and that was the first thing that we released after we were signed to Virgin. They thought they were going to get some quirky pop singles, but we were determined to make sure they understood what we were about. The general reaction to that song was, ‘What the f**k is going on here?’ Yes, we could write quirky, catchy pop songs, but we were not a pop group. Even the limited amount of technology that we were working with at the time still allowed us to do so much and I always felt it was my duty to push things as far as possible.

“Sorry, I wandered off, there. Today’s rig… Logic is the main platform. I’ve tried a few other platforms, but I can’t see or hear any reason to change. Even when it comes to mixing, I use a lot of the onboard Logic tools. Yes, I do dip into Waves and what have you, but that would usually only be the case if I’m looking for extreme effects. Heavy compression or massive signal degradation.”

Any room for the old hardware? System 100, the Fairlight...

“It was Ian who bought the Fairlight. Cost a bomb, looked fantastic, but the 8-bit sound was rubbish. I’ve still got my System 100. It doesn’t get used much, but, when I do use it, the difference in sound quality between that and any digital synth is huge.

“I’m not dissing the digital world, here, by the way. There are many wonderful things that happened after we went digital, but synthesisers have struggled since the release of the Roland D-50. Proper technical people have sat down and explained it all to me and, at its most basic level… there are fewer electrons flowing through the system in a digital synth. Companies have to use all sorts of techniques under the bonnet in order to try and get digital synths to sound analogue. And why do they do that? Because analogue sounds better!

“When I bought the plugin version of the System 100, I was quite dismayed to find that they’d added loads of bells and whistles. Instead of sticking with the original spring reverb, there are all sorts of other reverbs. Not needed. If I want to add effects, I can do that myself. There’s nothing wrong at all with pushing softsynth technology forward, but what is this obsession with extra features?

It was Ian Craig Marsh who bought the Fairlight. Cost a bomb, looked fantastic, but the 8-bit sound was rubbish.

“One of the companies that seem to have got the right idea – and I will admit here that I do know one of the people involved – is Nektar. With their synth, BOLT, they’re very much putting their trust in the user. Trusting them to understand the beauty and simplicity of analogue functionality. The original oscillator, filter and VCA architecture.

“I have to use plugins when we’re playing live, because there’s no real way that we could take the System 100 out on tour. Having said that, I did take the Korg out for a couple of dates recently. The first time it had been on stage in 40 years. Me and Glenn have got a nice line in patter, and we set it up for the encore… ‘Martyn’s got his first synth with him. The one he used on Being Boiled’.

“Then I play the first three notes. After an entire gig of digital synths, the crowd finally hears something analogue and it seems to work at a very deep psychoacoustic level. There’s a weight and a solidity that shocks the audience and they go mental. Maybe that should be the selling point. Analogue synths… they’ll send you f**king insane!”

What next for music tech?

“I’ve been mentoring doctorate students on the Media and Arts Technology course at Queen Mary University and there’s a lot of talk about interaction. The convergence of different worlds… sound, light, AR, VR, XR. Again, there’s much to applaud, but I still think we’re some way short of the day when people will sit in a concert hall with a device on their head that allows them to listen to and watch augmented reality. At the moment, people are still hungry for communal experiences. They want to join together… they don’t want to be separated.

Analogue synths… they’ll send you f**king insane!

“I just got hold of the Roland System-8, which is the latest hybrid of virtual and real synths – the Plug-Out system. It’s triggering a lot of memories. Reminding me of what I loved about analogue synthesisers in the early days.

“Perhaps the most interesting thing on the horizon is the idea of AI/neural network-driven composition. Let’s imagine a tool that sits on your computer, constantly and invisibly analysing and learning your compositional habits. It works out and stores your preferences in the same way that Amazon works out what you might want to buy.

“At first, you might think, ‘Oh, no. The robots are taking over. It’s Skynet in real life’. Not really. It’s just a way of organising your thoughts, then taking them out of your head and putting them into the computer. A program that will suggest a possible bassline when you’ve got writer’s block.

“Maybe one day, we’ll each have our own sonic, compositional butler!”

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)