Yes' Steve Howe talks guitars, prog, file-sharing and playing classic albums live

The lead singer spot in Yes has been a bit of a bouncing ball lately: Following the 2008 departure of longtime frontman Jon Anderson (who himself has skipped from the band from time to time), the progressive rock giants continued on with vocalist Benoit David, who had to bow out in 2012 due to a respiratory illness. On the group's forthcoming album, the Roy Thomas Baker-produced Heaven & Earth, the singing duties are handled by a new recruit, Jon Davison.

Heaven & Earth sees most of the core classic lineup of Yes intact: Along with founding member and bassist Chris Squire, there's drummer Alan White (who joined in 1972, replacing Bill Bruford) and guitar virtuoso Steve Howe. Rounding out the band is keyboardist Geoff Downes, a onetime member of the duo The Buggles (which featured the short-lived Yes vocalist Trevor Horn, who would go on to produce smash albums for Seal, Frankie Goes To Hollywood and Yes, among others).

Howe sat down with MusicRadar to talk about how Davison joined the band, performing the classic albums Close To The Edge and Fragile live, working with Roy Thomas Baker, prog rock and what he would like in return from all those who download Yes music free from the internet.

So there’s a Foo Fighters connection to your new singer, Jon Davison. I understand that Taylor Hawkins recommended him to Chris Squire, who then pitched him to the band.

“You know, I don’t know how that happened, really. I know that there are some friendships there, yes. Before that went on, I think Paul Silveira, our manager, recommended Jon, and we looked at him on the internet. Then, I think, some of the guys said, ‘Oh, yeah, he’s really good.’”

What was the process of him joining the group? He was in a Yes tribute band called Roundabout, right?

“Well, he wasn’t, actually. He did some work doing some Yes songs; he was in Glass Hammer, which is a prog band, not a Yes tribute band. He’s done a variety of things. He’s not always been a lead singer – he’s spent a lot of time being a bass player. I mean, I guess he did something in a Yes tribute band, but that wasn’t his primary musical venture. He’s had quite an illustrious career, and some of it was singing a bit of Yes. That’s what we saw in a medley.”

The new album – I wouldn’t call it prog rock, although the last song, Subway Walls, is total prog.

“Well, yes, I guess so. But see, when somebody at Mercedes-Benz goes to work, they don’t ask themselves if they’re an Audi or a Volkswagen. They know they’re a Mercedes-Benz. When Yes goes to work, we don’t ask ourselves if we’re another band. We’re Yes. But that’s a pretty broad stroke.

“I mean, when you look at Open Yours Eyes or other albums we’ve done – including Talk, which I wasn’t part of – you can see that we deviate from being just another straight-ahead, thoroughbred prog band. After all, you have to remember that we took nothing but criticism in Europe and England for being a prog band. [Laughs] So you can’t blame us for sometimes wanting to edge away from it. But we don’t do that because we want to; we do that because of the material we’ve got.

“It was the same with Fly From Here: When we started it, for good or bad, we didn’t say, ‘Oh, we’re not gonna make this record ‘cause it’s not prog.’ Or ‘We’re not gonna make this record ‘cause it’s too prog.’ Therefore, we would have upset everybody who thinks we’re indulgent, technical show-offs. We were never that. Right through the ‘70s, all we were was an honest band that did what we did. And that’s all Heaven & Earth is.

“We can’t change our mold. On this record, we’ve just got those songs. Some of them were a little bit dangerously close to being accessible, but some of them might not be dangerously close to being accessible. We don’t have a mold. I mean, I love the Keys To Ascension and I love the ‘70s, but we’re not always there. We just have to accept that, and so does our audience."

Yes, 2014

“In some ways, some people in our band might be trying to appease people and give them something accessible. Maybe we can give them an album of silence. [Laughs] But I can say that we are more accessible – as writers, that’s what comes to us. I don’t disagree with your comment about Subway Walls. It’s a profoundly good arrangement; we really developed a lot of ideas. I think it shows what weight Jon Davison has brought to us. He collaborated on the music with Jeff as much as I did with him on Believe Again.

“It’s a real mixed bag of writing, and it isn’t all the same, thank goodness. Some of it does lean a bit to close to ‘la la la-la-la,’ but that’s what we are.”

You worked with Roy Thomas Baker, whom you had tried working with in 1979. Was that for the record that became Drama?

“No, no, that wasn’t Drama. We had tons of material that had nothing to do with Drama. All of that material was canned. It was old, Alan broke his foot… We didn’t have the right material for an album, and we didn’t continue making an album. Besides Roy buying a new Trans-Am, that’s all we knew. We left, we didn’t get to know Roy that well – I can’t say that we really know him now.”

Why did you decide to give Roy a call after all these years? Did it feel like there was unfinished business with him?

“Well, like anything, the answer’s too obvious – it’s what we chose. Out of the people we’d approached, and out of the people who came back to us and said, ‘Oh, yeah, I’d like to work with you,’ we weighed them up and took a chance with Roy. Much like when people asked me, ‘How did you pick the group name of Asia?’ I tell them, ‘We had 10 group names, and we took nine of them off.’ [Laughs] That’s pretty much how it works in life. We met Roy, we talked, and that was it. I’m not going to say any more about it.”

Was it an unpleasant experience working with him? You say you don’t know him even now after making a record with him –

“I’m just gonna leave it at that. We still don’t know him that well.

You had Billy Sherwood mix the record. Obviously, he’s somebody you know very well.

“We made the record, and we asked Billy to mix it – we just didn’t feel that it was quite Yes. Billy has a history with the band, and he’s obviously done good things when he was in the band, so therefore we trusted him, with our involvement, to do that. That’s how the swinging roundabout came; we might have been going around with this with Roy Thomas Baker, but that’s not how we finished it. We wanted Billy to bring it back to Yes Central."

On file-sharing

“It’s an up-and-down relationship with Billy. He did some work on the Keys To Ascension project, which was great. He recorded studio tracks to what we eventually added to an album called Keystudio, which was just the Keys To Ascension studio music, and I thought it was very valid. Billy was engineering and helping us mix those. Then, of course, he wrote some songs with Chris, and that became the Close Your Eyes album. At that point, he came in the band, and Jon and I only made small contributions to that album. So Billy stayed with the band for a while…

“He’s watched us do this and that, and he made a few records with Chris. Then Billy and I did some things, various projects like Pink Floyd. We just did one for The Doors where I play on Light My Fire. So Billy and I get on. We’ve had wars, but we’ve also had friendship.”

Is your motivation for making albums the same as it was in the ‘70s? So much has changed in just the past 10 years alone, not the least of which being the role of the album itself in culture.

“Well, it’s funny you use the word ‘motivation.’ That sets a whole agenda here – inspiration, motivation, need, desire… I don’t know if I can really answer that. That’s a whole… The whole landscape has changed. If everybody who ripped off our album were prepared to give us two months' work of their lives for free, then maybe it would be a very well-balanced situation. So if you wanna take the album, then give us two months of your work for free.

“That’s basically what people are doing. They’re taking more than two months – but let’s just whittle it down to two months' studio work – that we sat in an expensive studio trying to make a good-quality record, and then people just take it. So the reason why we do this has changed a lot. Some people in this band might say that the reason why we do it is because we’re musicians and we’re supposed to make new music. But that’s a bit blind. That’s a little like a mouse saying, ‘I’ll walk across this road even though there’s a cat on the other side.’ [Laughs]

“Now, I don’t only make Yes records; I make different sorts of records, and the motivation is vary different to all of them. It took me a long time to decide that I would agree to do this record. These older bands making records with all of these expectations that they’re gonna rush up the charts and everyone’s gonna love ‘em – it’s fizzling. So that’s not what happens.

“The Rolling Stones, The Who, Aerosmith, you know, they make records and they don’t even chart! [Laughs] And yet, these are some of the biggest bands in the world. Yes needs to learn this. We need to remember that what’s happening out there is a very, very different scene, and it’s partly due – mostly due – to the internet. People got the needle about labels making money, but they have to because they have to print, distribute and promote the record, and give us a lousy percentage. Yeah, I could moan about that."

On classic albums

“But now we’ve got the situation where people take the music for free because they somehow think that’s their right. And as I said, give me two months of all of those people’s work and energy. I wouldn’t say that I’ve a grudge, but you know, it does hurt. It does grieve me that our rights and our copyrights are abused all the time. And yet, we’re stupid enough to go and make another record, which immediately is put on the internet by somebody. The whole album on the internet!

“I mean, that guy ought to stop and think about giving us two months of his life for free. Do these people do anything for free? I don’t think they do. They get a job, they get paid. Do they walk in to their boss and say, ‘I don’t mind working for free’? The guy would look at him and say, ‘You’re gonna work at my company for nothing?’ ‘Yeah, yeah. I steal records off the internet, and I work for free!’ [Laughs] That would be unheard of. So musicians and filmmakers and authors – we’re all expected to do this for free.

“So the inspiration is quite different. I make time, I make my Homebrew series, I’ve done records with Asia – I do things for quite a few different reasons. But when it comes to a high-profile group like Yes… It’s a very complicated question you ask me. Let’s move on. Don’t comment, just move on.”

On this tour, Yes are performing Fragile and Close To The Edge in their entirety. As great as it is to have a couple of classic albums in your catalogue, is it ever a drag that newer material doesn’t get the same reaction as, say, Roundabout?

“Well, we can’t deny that. We can’t go against the grain. Close To The Edge and Fragile were both made in the same year, and they’re remarkable records with remarkable production, assisted by Eddy Offord. The band is remarkable, with Bill Bruford chopping away at his most creative at that time. I fully understand why they’re not screaming for Open Your Eyes. I know why they don’t want us to play much of Talk. We’re not stupid. We know what went down well, and we know that, for years, Fragile and Close To The Edge were sensational-selling albums. We’re very proud of them. Let’s just talk about how proud we are, not that we’ve got some albatross.” [Laughs]

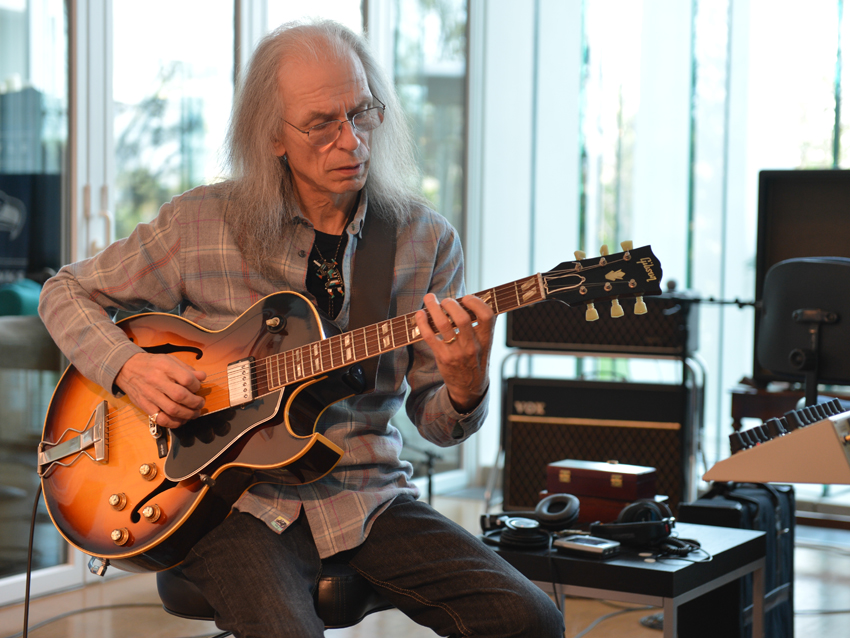

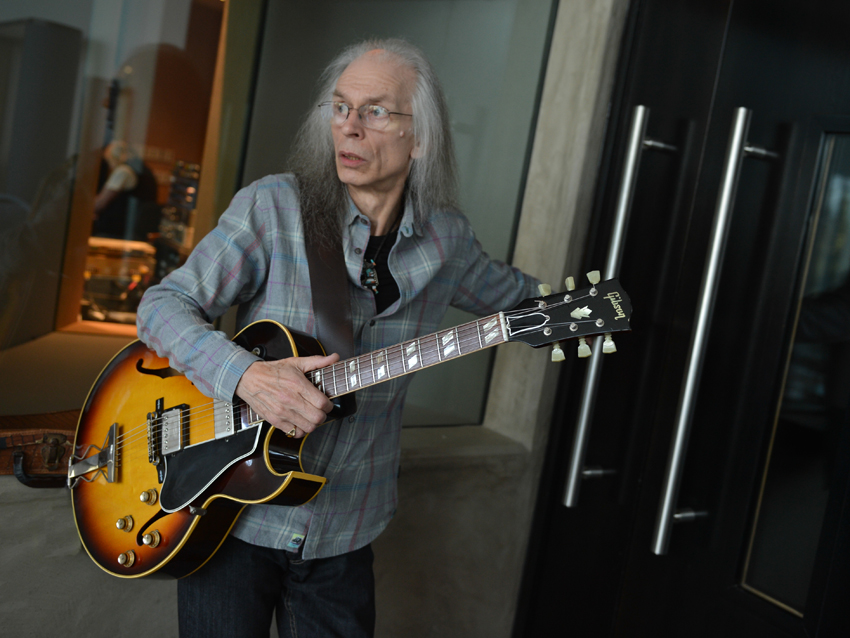

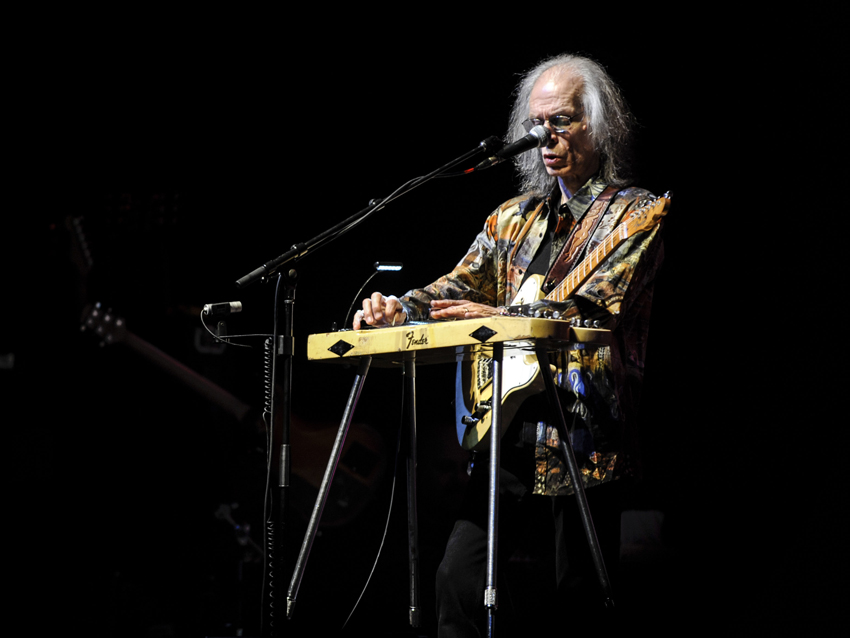

On pedal steel guitars

Are there any new guitars that you’re currently using?

“Yeah, but you have to realize that newer guitars aren’t my biggest feature. I’m actually playing a brand-new Martin 000C – I’ll use that for Mood For A Day. I’ve brought back into action my 1960 ES-5 Gibson Switchmaster, which is one of the most amazing guitars I’ve got. I’m using my Fenders and my steel and things like this, so tonally it’s a well-rounded show. I continue to like contrasting sounds over different types of electric guitars. I still use a 345 Stereo because it’s such a great guitar to play. Mix that with the steel and the Variax guitars… I like the older one because it fits on a stand. Guitars are always shifting, like the sand. There’s some greater appreciation I can realize for some older guitars, but then a new guitar will come along that really works well for me, like the Martin 000C.

“In the electric guitar field, my Steve Howe 175 is one of the guitars I play. Like the Switchmaster, it’s a three-pickup model – a three-pickup custom. Guitars come in and out. I love them. I bought quite a few steel guitars recently. I’m still searching for a single-neck Professional with legs steel guitar, but they’re very, very rare. People think I want to buy a Champ or something, but I don’t want one. They don’t have the double pickup, and they’re not substantial, professional instruments.”

Are there any guitars you record with that you won’t take out on the road?

“Well, I started doing that with my best 175 because airlines – let me just take a deep breath… airlines understand that there are rules, but they change them. One day, a few years back, I got to Heathrow and they told me I couldn’t take my guitar on. I literally freaked out, and I said to the whole gate – I pulled my guitar out and I said, ‘Can you believe this? This guitar, they won’t let me take it on. Can you believe that?’ And everybody cheered, but they still wouldn’t back down.

“I’ve got these people. I mean, I complained vigorously after that. They told me to go home and get another plane. Can you imagine? I mean, I’m not an egomaniac, but I am Steve Howe – I’ve got some credibility. I do have a reason why I want that guitar to go on. So it’s a mixed bag. The 175 from 1964 is not going on any more planes.”

Yes' Heaven & Earth will be released on July 22. You can pre-order the album on Amazon.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.