Hail, hail rock 'n' roll: the Chuck Berry story

On his birthday, here's The Father of Rock 'n' Roll's origin story

The late '40s and early '50s were a seminal time. Jazz, blues, country, R&B and rock ’n’ roll were being born or undergoing significant changes.

Also emerging were the first great wave of pop singer-songwriters. From this group of young pioneers came a genius, writing lyrics, melodies and riffs that provided the bedrock for almost everything to happen since.

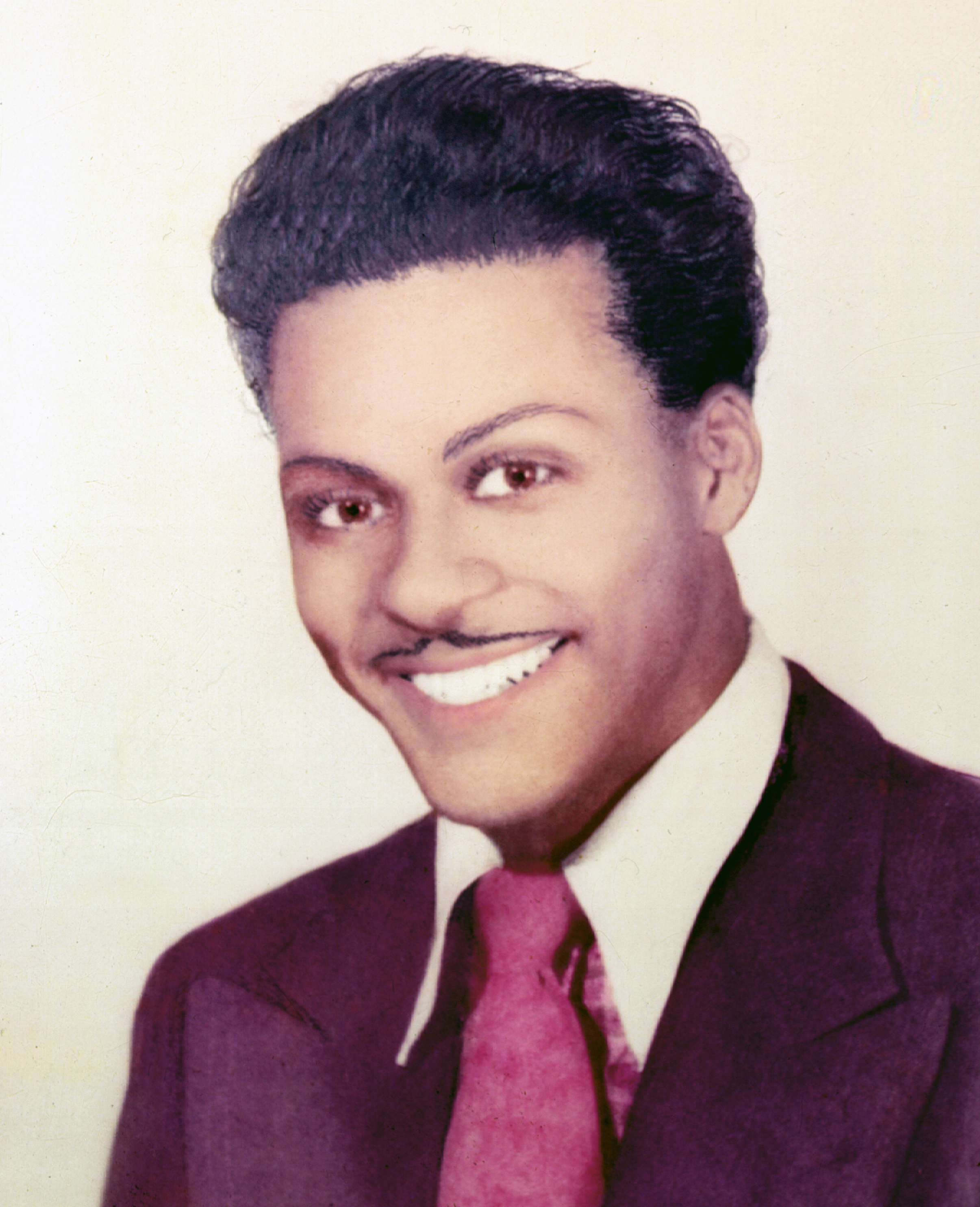

Chuck displayed an interest in music and poetry from a very young age

Charles Edward Anderson Berry was born into a large, middle-class family in St Louis, Missouri on 18 October 1926, the fourth of six children to Martha and Henry Berry.

Henry was deacon of the Baptist church in the area of St Louis called The Ville, where the family lived. Martha was a school headmistress, which meant that Chuck and his siblings enjoyed a relatively prosperous upbringing contrary to that of so many black (and white) families in the 1920s and 30s.

Chuck displayed an interest in music and poetry from a very young age and, encouraged by his parents, progressed quickly, making his first public appearance in 1941 at the age of 15, while still at high school.

The song he chose, Confessin’ The Blues, by Jay McShann, was a big band hit at the time and boasted in its ranks another fledgling genius in the form of alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, one of the inventors of be-bop jazz.

Chuck’s first of many brushes with the law occurred three years later when he was arrested, and convicted, of armed robbery. He was sentenced to three years at the Intermediate Reformatory for Young Men in Algoa, Missouri, where he took up boxing along with forming a vocal quartet.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Picture a young man working in a mundane job but composing riffs, rhythms and lyrics in his head to the beat of the factory machinery

On the day of his 21st birthday in 1947, Berry was released from custody, and shortly after met Themetta Suggs. They were married in October 1948 and had a daughter Darlin Ingrid, born 3 October 1950. Berry worked in a variety of jobs in order to support his young family, including - significantly - two stints at car assembly plants in St Louis.

Knowing, as we do, the abundance of motor-related metaphors in his later songs it’s intriguing to picture a young man, bursting with ideas, working in a mundane job but composing riffs, rhythms and lyrics in his head to the beat of the factory machinery.

Curiosity provoked me to lay a lot of country stuff on our black audience... they began requesting the hillbilly stuff

Chuck Berry

By the early '50s, Berry was also ‘moonlighting’ with local bands at clubs in and around St Louis; graduating to a regular group in 1953 - the Johnnie Johnson Trio - which held a residency at the Cosmopolitan Club.

Playing mostly blues and ballads at gigs, Berry began to take an interest in presenting some country-flavoured tunes to the club’s black audience, and later wrote:

“Curiosity provoked me to lay a lot of country stuff on our black audience. After they laughed at me a few times they began requesting the hillbilly stuff and enjoyed dancing to it.”

With an idea formulating in his head that a fusion of blues and country might make for a new sound, another major influence came along in the form of R&B maestro T-Bone Walker.

T-Bone, along with his jazz-playing contemporary Charlie Christian, was instrumental in elevating the guitar from its former position as a rhythm tool to that of a front-line solo voice.

Walker was also a consummate showman, playing the guitar behind his back whilst doing the splits and delivering solos that, at times, would make an audience think his guitar was speaking to them.

The huge success of both Berry and Presley serves as proof that the best music always comes from a mixture of cultural influences"

Chuck Berry was so taken with Walker that he lifted many of T-Bone’s trademark licks, doublestops and unison bends, incorporating them into his own emerging style.

Johnnie Johnson left the trio in 1954, with Chuck renaming it the Chuck Berry Trio. Having taken charge, Berry’s mix of blues, country, Nat ‘King’ Cole ballads and T-Bone Walker showmanship propelled the trio to new heights. They quickly became the most popular band on the St Louis club scene.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this is how Berry’s ‘new’ music almost exactly mirrored that of his nearest rival in the 50s, Elvis Presley. Where Berry took blues and added country to create a potent formula, Presley did the opposite by adding blues to country (one of Presley’s major influences was Chuck Berry!).

The huge success of both Berry and Presley serves as proof that the best music always comes from a mixture of cultural influences, and also that it could only ever have happened in the USA.

As Chuck’s popularity grew, so his ambitions gathered pace. Feeling that he was ready to record his music, he travelled to Chicago and, through a meeting with Muddy Waters, was encouraged to approach the iconic Chess label with a view to scoring a recording session.

The combination of blues and country flavours allowed Maybellene to become a huge hit with record buyers of all races

Label boss Leonard Chess was particularly taken with a song Chuck brought in called Ida Red, a traditional ‘hillbilly’ tune made popular by Bob Wills And His Texas Playboys back in 1938. Lyrics were changed and the song retitled as Maybellene, with Berry taking the songwriting credit. The 21 May 1955 recording date features, among others, Berry’s old boss Johnnie Johnson on piano and blues giant Willie Dixon on bass.

From the first bar, this was something new. Berry’s guitar, despite betraying the T-Bone Walker influence, is raw, energetic and infectious; relentlessly rhythmic and driving behind the vocal, then piercing through with classic Berry attitude in the solo.

The combination of blues and country flavours allowed Maybellene to become a huge hit with record buyers of all races, selling more than one million copies and going to number one and number five on the R&B and Billboard Best Sellers charts respectively.

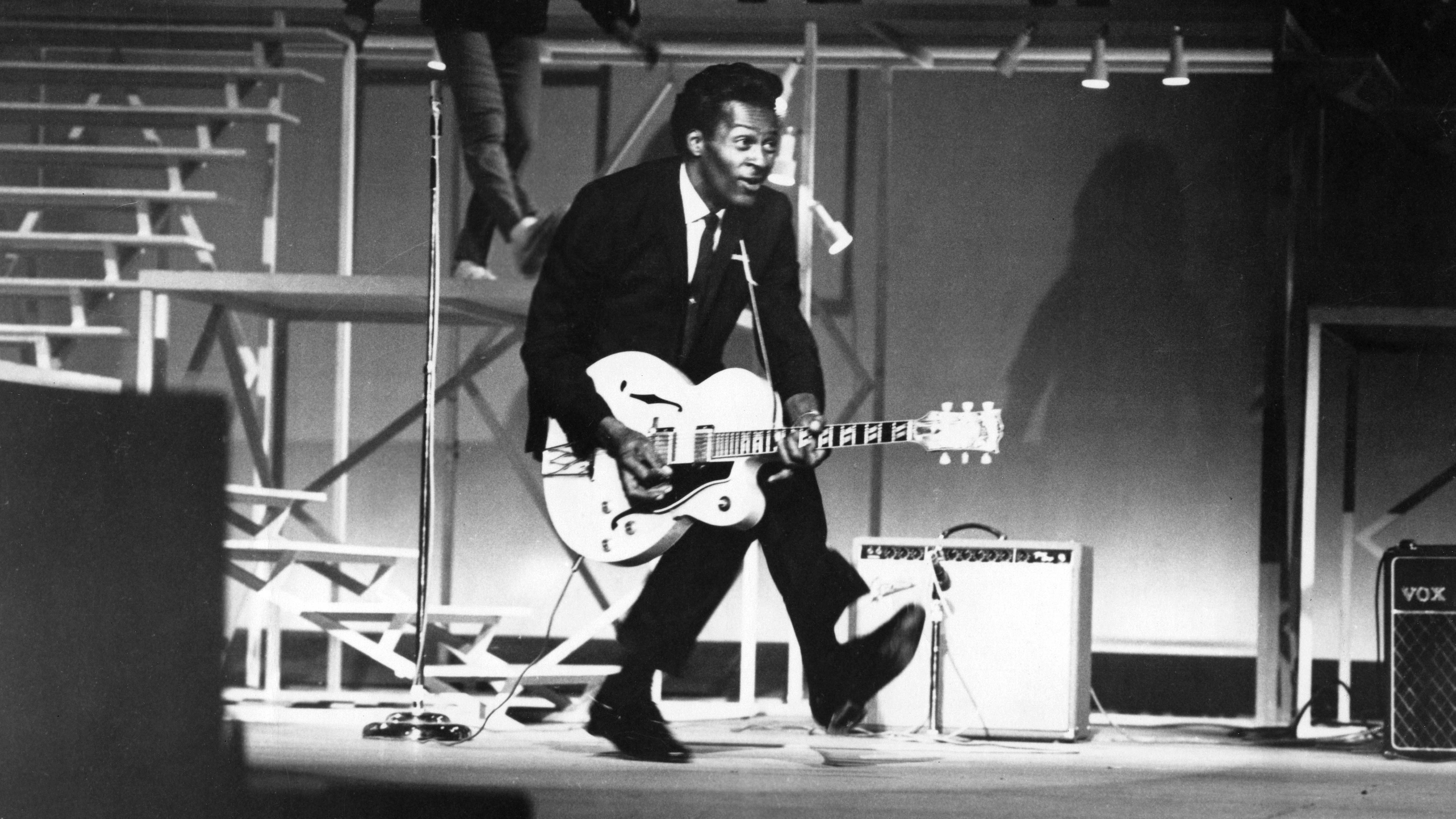

This mix, coupled with Berry’s dynamic stage act, propelled him to overnight super-stardom, and from then the hits came thick and fast, all classics, including Roll Over Beethoven, Too Much Monkey Business, Rock And Roll Music, Sweet Little Sixteen, Memphis Tennessee and the iconic Johnny B Goode; all recorded between 1956 and 1959.

Berry went from earning $15 a night to more than $1,500 - a fortune in the 1950s

In all, Berry scored over a dozen hit singles during this period. Berry went from earning $15 a night to more than $1,500 - a fortune in the 1950s. He invested heavily in St Louis real estate and even opened up a racially mixed nightclub - pioneering for its time - in 1958.

By December 1959, and seemingly with the music and business worlds at his feet, Chuck Berry again found himself on the wrong side of the law when he was arrested following allegations that he had sex with 14-year-old waitress, Janice Escalante, whom he had transported over state lines to work at his club as a hatcheck girl.

Berry’s appeal at the 1960 trial, where he accused the judge of racial prejudice, was upheld and a new trial set for May 1961. Chuck was eventually convicted and served 18 months of a three-year sentence, being released in October 1963.

Over the four-year period between his initial arrest and release from prison, his popularity had waned and his output slowed, despite Chess continuing to release material already ‘in the can’.

By 1963, however, the music scene on both sides of the Atlantic had changed drastically which, with a little help from some young lads from England, proved to be just what Berry needed to get back on top.

Rock ’n’ roll, blues and R&B records had been making their way across the Atlantic for several years and were causing a huge stir among British youth.

This movement was instrumental in bringing the music of Chuck Berry and his contemporaries to a new audience, with bands such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones recording versions of Berry’s songs on their early albums.

There was a time in my life when Chuck Berry was more important than anything else

Keith Richards

John Lennon famously said “If you tried to give rock and roll another name, you might call it Chuck Berry.” For Keith Richards, “There was a time in my life when Chuck Berry was more important than anything else.”

Chuck was able to secure a new record contract with Mercury Records and released several singles and albums between 1963 and 1969, including the classic No Particular Place To Go, yet another automobile-related song. Despite not achieving his previous success on record, Berry became a fixture on the touring circuit, and came to the UK in 1964 and ’65.

His stint in prison had, however, turned him into a moody and bitter man. This, coupled with his reluctance to rehearse with the pick-up bands he played with, earned him a reputation as a difficult person to work for.

He insisted on being paid in full, and in cash, before he would walk on stage - which eventually got him into trouble with the taxman - and, as time went on, his performances became ever more erratic, serving to alienate his loyal fans.

By the end of the '60s, disillusioned with Mercury, Berry returned to Chess, scoring an unlikely hit with an innuendo-laden ditty called My Ding-A-Ling in 1971, a song that earned him his first official gold record.

Throughout the 1980s, Berry continued to play up to 100 concerts per year, picking up local musicians along the way

Through the 1970s, and buoyed by the success of My Ding-A-Ling, Berry once again became a headline attraction at clubs, concert halls and festivals, culminating with a performance, at President Carter’s request, at the White House.

In 1979, the IRS finally caught up with him and, pleading guilty to tax evasion charges, Berry was sentenced to a combination of a short prison stint and community service.

Throughout the 1980s, Berry continued to play up to 100 concerts per year, picking up local musicians along the way, sometimes good, sometimes awful, but always willing to put themselves through anything for a moment on stage with a legend.

Berry’s reputation was again tarnished in 1990 when several women sued him, claiming he’d installed video cameras in the ladies’ lavatory at his restaurant, The Southern Air. The police raided his home and found video tapes, one involving a minor, along with a large amount of marijuana.

This time, Berry got off relatively lightly with a suspended jail sentence and community service. Berry was also sued by former bandleader Johnnie Johnson, who claimed he’d co-written many of Chuck’s hits. This time, the case was dismissed.

Despite his obvious dark side, what remains clear is what a pioneer and innovator Chuck Berry was in the 1950s; he crossed racial lines with his fusion of country and blues, and his groundbreaking songwriting inspired so many up-and-coming musicians on both sides of the Atlantic.

Chuck Berry features in almost every 'Greatest Ever' list one can name

He also was rock ’n’ roll’s first guitar hero frontman, and for that alone, he will always be revered and remembered.

Chuck Berry features in almost every ‘Greatest Ever’ list one can name - a testament to his lasting influence and timeless music. His songs have been covered by everyone from Elvis Presley to Ted Nugent and his dynamite stage act, including the famous ‘duck walk’, has become the blueprint for the presentation of rock music from the 1960s to today.

His guitar style, although not ‘technical’, was so influential that the intro to Johnny B Goode, for example, is still taught to young and aspiring guitarists well into the 21st century. Perhaps that is what will serve as the ultimate tribute to this undisputed, but troubled, genius.