Wes Montgomery: a player's perspective

Steve Howe, Martin Taylor and more on the jazz legend

With the recent release of In The Beginning, a double-album set on Resonance Records that features newly discovered 'live' recordings and studio sessions, we ask: what makes Wes Montgomery so special? Why is he still relevant today? And what can all guitarists, regardless of style, learn from this humble genius?

Throughout the 1930s and 40s, guitarists were faced with a major challenge: how to adapt the 'language' of jazz on to the fretboard. From its seedy beginnings in the Red Light District of New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century, jazz had been a horn players' music. So much of the basic vocabulary centred around the way trumpets, saxophones, clarinets and trombones slid, bent, glissed and sustained their phrases.

For years, the humble guitar languished in the rhythm section, where it thumped along with the bass and drums while horn players wailed out front.

Early solo pioneers such as Eddie Lang, Lonnie Johnson and Django Reinhardt paved the way for the single-string genius of Charlie Christian who, blessed with the new-fangled electric guitar, was able to forge its place in the 'front line' of jazz ensembles.

Christian's contribution started a revolution. Guitarists were finally liberated - and among them was Wes Montgomery.

The Thumb

Wes was entirely self-taught and early on decided to sacrifice speed for tone by using the right-hand thumb instead of a plectrum. The fat, warm sound he was able to produce with the thumb created a very vocal, soulful 'voice' that's very difficult to obtain with a pick.

"His technique seemed to allow him to play anything he wanted" - Steve Howe

Most players who try this technique find it stifling, as upstrokes are so difficult to articulate. Jim Mullen, himself a thumb player, points out that Wes "had a double-jointed thumb, which meant he could play both up- and downstrokes like a pick player".

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Ultimately, Wes became so good with the thumb that any drop in speed became irrelevant, as Steve Howe points out: "His technique seemed to allow him to play anything he wanted."

Listening now, over 50 years after some of his most celebrated recordings were made, the velocity Wes could generate when needed is still astonishing. A prime example is his solo on the John Coltrane tune Impressions, which he takes at a breakneck speed. In fact, there isn't a single moment in any Wes recording where you would think he'd do better with a pick!

Picky about picks

"His technique shouldn't have allowed him to play fast, but... he could play fast!" says John Etheridge, although speed-for-speed's-sake was the last thing on Wes's mind. He always seemed to play exactly what was right in any given musical moment and was much more interested in generating a 'mood'.

The tone produced by his magic thumb was a prime ingredient in Wes Montgomery's emotional arsenal. On top of this, Wes had his own way of emulating the horn style of jazz phrasing by, in the words of Nigel Price, "constructing a huge vocabulary of slides, hammer-ons, pull-offs and slurs, which set him apart from all the other guitarists of the day".

Herein lies a major component of what makes Wes so great. He was, arguably, the first jazz guitarist to fully incorporate the legato approach of the horn players, and we can speculate as to how much the thumb approach contributed to that.

Adrian Utley makes the point that the thumb gave Wes "a great 'connection' with his instrument... no plastic pick to get in the way". This also played a large part in his beautiful, relaxed phrasing, which, coupled with his innate musicianship, produced playing that is as moving as it is awe-inspiring.

The 'Formula'

"I was immediately struck by the energy, sophistication and sheer joy in his playing" - Martin Taylor

"I first saw Wes on a BBC TV show in the 60s," recalls Martin Taylor. "I was immediately struck by the energy, sophistication and sheer joy in his playing."

It's difficult to imagine the impact that Wes had when he first came to prominence. As Steve Howe says: "The newness of the sound that Wes brought to us in the 1960s was so refreshing."

What was it, then, that set him apart from other great guitarists of the day? The answer, perhaps, lies in his unique approach to soloing, which became something of a 'formula' and ultimately defined his art.

The formula itself? Single-line passage, octave passage, block-chord passage was a beautifully simple way of building subtle intensity as the solo developed and yet another indication of his genius. Horn players - having a broader palette of range, dynamics and tonal colours - were able to build their solos by introducing those elements as the solo developed.

Thick solos

Certainly in those days, guitarists had just one sound at their disposal, making it more difficult to maintain interest and intensity when they played. Wes found a brilliant and simple way round this problem by, as John Etheridge points out, "reinforcing" and "thickening" his lines as his solo progressed.

After a passage of fluid, bluesy, always relaxed single-string licks, Wes would move onto octaves for the next stage, and play them so effortlessly that you would hardly notice the transition. Yet, the line is now doubled and intensity is added to the solo.

The last phase of the solo would see Wes move from octaves to full chords - known as 'block' chords - which would further increase the drama and excitement. John Etheridge elaborates:

"All three were used strictly melodically, the single line reinforced with octaves, essentially thickening the line. Then, his chord improvisations - and this is very important - were also used melodically. It wasn't like, 'Look, I can do this harmonic inversion of this substitution.'"

Each device follows as a natural progression from the other. There are countless examples of Wes employing the 'formula', although West Coast Blues epitomises the technique.

The key, as Jazz player Jim Mullen points out that Wes had a double-jointed thumb, enabling him to play both up- and downstrokes Etheridge points out, is melody and melodic drive. Jim Mullen adds:

"His octave playing was an imitation of the trumpet-tenor sax frontline and his improvised chord solos were beautiful, melodic inventions."

Steve Howe describes Wes as a "brilliant, naturally gifted improviser", and Nigel Price emphasises how one "rarely gets the feeling that Wes is forcing through pre-learned patterns, unlike many jazz guitarists today".

Natural is a key word. Wes played in a way that is increasingly absent from jazz these days. He sounds like he doesn't care about scales, modes, substitutions or clever little 'guitaristic' devices. His playing exists solely in the pursuit of melody. As Adrian Utley says about another Montgomery masterpiece, D-Natural Blues: "You can sing the whole thing: it's so melodic, perfect and succinct."

The Blues

Wes Montgomery was a master of the blues. Regardless of how complicated the chord changes or melody of the tune he was playing, it was always laced with the blues. Wes recorded many variations on the 12-bar throughout his career: the aforementioned D-Natural Blues, as 'down-home' as it gets; and the loping waltz time of West Coast Blues, with its lovely 'twist' in the chord pattern.

"Wes sounded so effortless, his rhythmic feel was so 'in the pocket', relaxed and flowing" - John Etheridge

Other prime examples are Blue 'N' Boogie, a medium-up-tempo swinger, and Cariba, a minor blues with a Latin feel. Then there's the unusual 16-bar Twisted Blues, which features some fabulous alterations to the standard sequence, as its title suggests.

Regardless, Wes played real blues on everything - meaning 'blues, the attitude' rather than 'blues, the pentatonic scale'. John Etheridge reminds us that Wes "sounded so effortless, his rhythmic feel was so 'in the pocket', relaxed and flowing. Everything he did was beautifully played and phrased, it was so sensitive... he makes you 'feel' the song, which is very important... he really does tell a story."

A musician first

Of course, telling a story has its roots in the blues. When you listen to old live recordings of, say, BB King, you can hear the crowd responding vocally to phrases he plays - call and response - and you can hear the jazz equivalent with Wes.

He'll put a 'full stop' on a phrase at the perfect moment before picking up the next idea. Subtle use of space was as powerful a tool in Wes's hands as all the blistering single lines, octaves and chord melody he'd mastered.

Knowing when not to play, creating momentum with subtle but brilliant rhythmic devices, holding back, pushing forward. There's such a vocal quality to Montgomery's playing that you could almost fit lyrics to his lines - "you can sing the whole thing!"

In some ways, he was the most un-guitar- like of guitar players. His musicianship transcended his chosen instrument. Martin Taylor reinforces this point when he says:

"Django has gone down in history as a great guitarist but I always think that Wes was a musician first, a guitarist second. Wes would have been a great musician whatever instrument he chose to play."

Transcribe a Wes Montgomery solo for a sax player and what you will hear is a great jazz solo, exactly as Taylor describes. Nigel Price adds: "Wes played everything for the music. His improvisations were always in keeping with the vibe of the material." This was most apparent when Wes played his beloved blues.

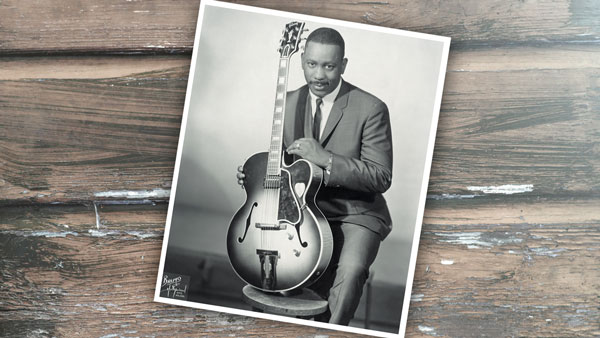

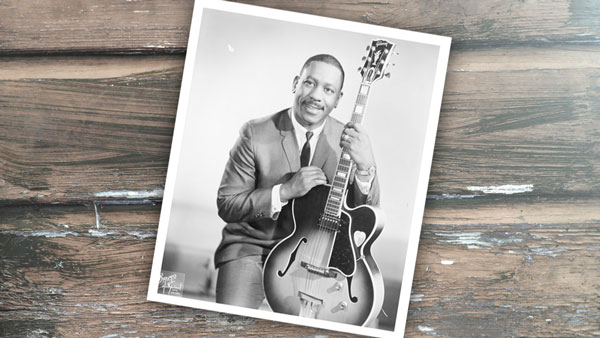

The Guitar

Wes owned and played a variety of Gibson archtops over the years that would have us all drooling. A Gibson L-4 with a 'Charlie Christian' pickup, an ES-175 and an ES-125 are all guitars he was photographed with in the early days. The instrument he'll be forever associated with, though, is the L-5.

Later in his career, Gibson made him a 'custom' model with a single neck humbucker and a metal tune-o-matic bridge to replace the traditional wooden one. This was Wes's request, as the metal bridge brightened the tone, offsetting the dark sound produced by his thumb. At some point, Wes had the pickup reversed.

Contrary to popular belief, he was constantly looking for ways to brighten the sound. His strings were, in the words of Russell Malone, "cables!" - 0.014 to 0.058. His choice of amp fluctuated between Fender Super Reverbs and Twins, before he switched to a Standel Super Custom in the mid 60s.

Regardless, Wes never cared too much about gear and saw his equipment as nothing more than a tool to get the job done, once saying, "I got a standard box. I don't never want nothing special. Then, if I drop it, I can borrow someone else's."

He also dabbled with a Fender electric bass. His brother Monk Montgomery is credited with being the first to play jazz on a bass guitar, so it was close to Wes all along. He even recorded some solos on bass for the Movin' Wes album, which Steve Howe describes as a "hidden gem in his crown".

The Legacy

For someone who was quite content honing his craft in jazz clubs around Indianapolis while supporting his wife and seven children by also holding down a full-time day job, Wes probably wasn't as ready for the limelight as much as the jazz world was ready for him to be there.

He was 37 years old when he was 'discovered' and signed to Riverside Records but had been quietly "reinventing jazz guitar" for over a decade, as Jim Mullen says, with nightly gigs on his local scene.

"I don't practise. Every now and then I open the guitar case and throw a piece of raw meat in!" - Wes Montgomery

The recordings just released by Resonance come from these times. Here, we can get close to the 'real' Wes, playing effortless jazz to a relative handful of clubgoers. We can hear him in a relaxed and informal setting playing for the sheer joy of it and clearly having the time of his life. The "relaxed but ferocious energy" that Adrian Utley describes is in evidence on these amateur recordings.

The years in the clubs meant that Wes arrived on the international scene fully formed, making him seem even more incredible when his albums first appeared. The fact that he lived fewer than 10 years between his first major album and his death only serves to add to the intensity.

That he chose, admirably it would seem, to 'sell out' to a major label and become a Grammy Award-winning 'pop' act toward the end allows us an insight into his philosophy on music and the guitar. He only ever saw it as "a hobby" and remained humble and down- to-earth while blowing everybody away with his incredibly joyous music.

Boundary pusher

He claimed not to practise, saying, "I don't practise. Every now and then I open the guitar case and throw a piece of raw meat in!" On another occasion, he elaborated: "If I know it, I don't need to practise it. If I don't know it, I ain't risking it!"

The fact is, Wes Montgomery was a man who genuinely did play for the love of it. He never allowed himself to be tortured by any technical shortcomings or threatened by the new generation of great players coming up in the 60s, such as Joe Pass or George Benson. He merely turned up at a gig or a studio and played heartfelt, honest, soulful and beautiful music before going home to his beloved family.

Guitarists of all genres have repeatedly acknowledged their admiration for Wes Montgomery. From Jimi Hendrix to Eric Johnson; from Steve Vai to Stevie Ray Vaughan; from Joe Satriani to Steve Lukather... Wes has never been just a jazz guitarists' favourite. His music has, and always will, defy categorisation and transcend musical boundaries. Perhaps this should serve as the ultimate lesson taught by this great man.

Many thanks to John Etheridge, Steve Howe, Jim Mullen, Nigel Price, Martin Taylor and Adrian Utley.