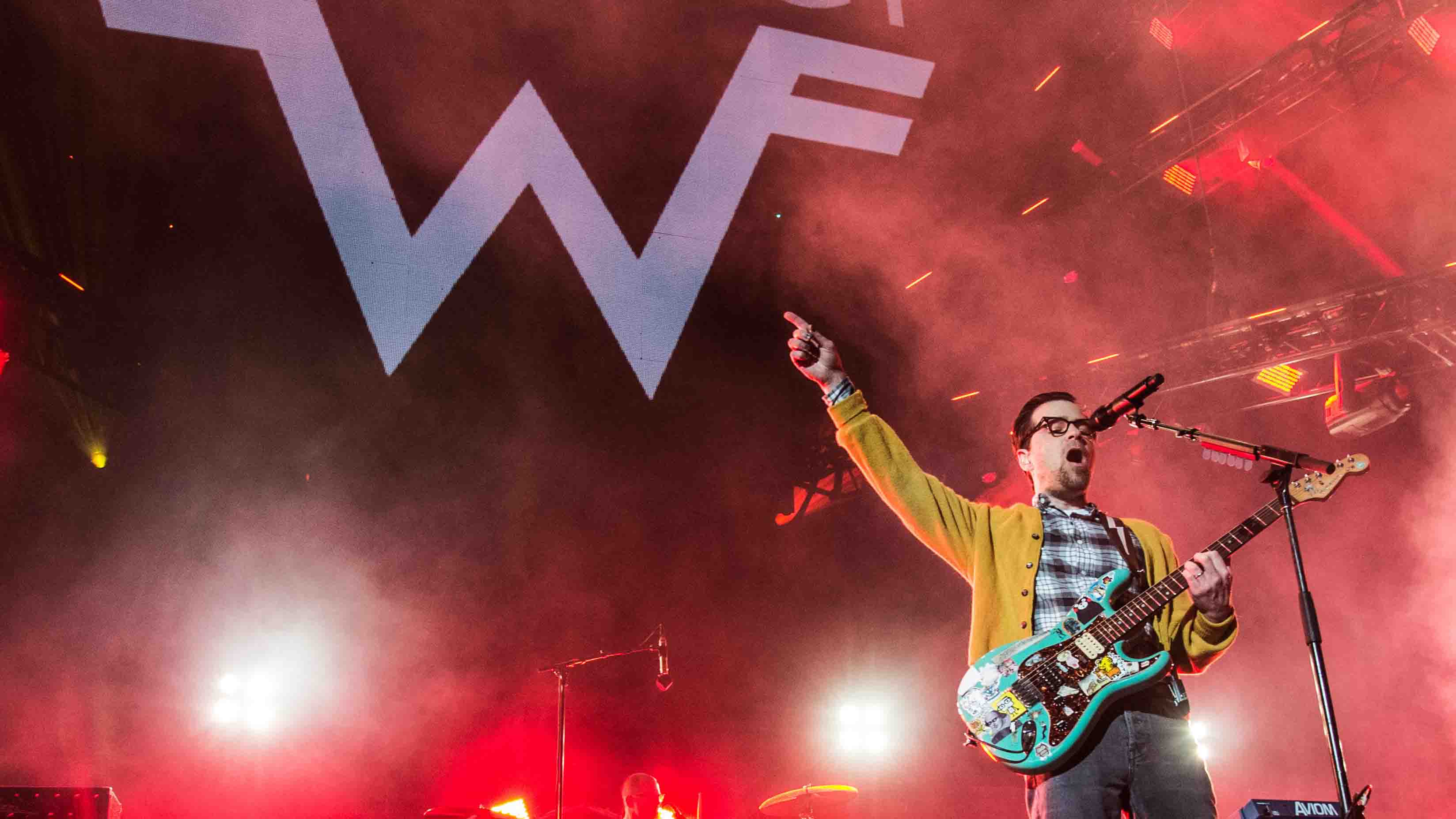

Weezer's Rivers Cuomo talks The White Album, channelling James Hetfield and his enduring love of guitar

"If I get up on stage without a guitar, it just doesn't feel right... I feel weak!"

Introduction: White on time

Half a decade ago, Weezer were a snobby music journalist’s punchline.

After a series of albums that had alienated both punters and critics alike, a fund-raising campaign was launched by a small group of fans who were convinced that the band were on an inexorable downward trajectory, the best course of action was to offer them $10 million dollars to break up.

We bet they’re feeling a bit sheepish today. 2014’s Everything Will Be Alright In The End – the band’s finest record in a decade – was a shot across the bow to those who doubted the ability of the band’s enigmatic frontman, Rivers Cuomo, to recapture the lightning in a bottle of My Name Is Jonas or Buddy Holly, but the follow up is a full-on barrage.

Weezer’s fourth self-titled LP (or The White Album, for simplicity’s sake) is 35 minutes of grunge-pop bliss – a hugely compelling blend of 60s vibes mixed with Rivers’ stock in trade infectious melodies, killer guitar hooks and blistering hair metal-inspired solos.

LA Boyz

Weezer formed in Los Angeles in 1992, and The White Album might be the band’s most overt love letter to the highs and lows of their home state yet.

Its cover depicts the foursome stood in front of a Baywatch-esque lifeguard tower on a pristine sandy beach, while the album is chock full of harmonies and chord progressions that nod to that most Californian of bands, The Beach Boys.

Despite the familiarity of those classic California Sound hallmarks, however, the songs still sound fresh and unmistakably Weezer. This trick of breathing new life into well-trodden chord progressions is something Rivers has done since the band’s earliest days, so we have to ask – what’s his secret?

“Yeah, I mean, you’re only hearing the best stuff!” the guitarist exclaims. “Many times when I sit down to write, I use an old familiar chord progression and it ends up sounding really boring or really tired. And then, I don’t know why, but one out of 10 times there’s some magic there and it works, even though you’re using that same old progression.”

Beach Boys progressions and infectious guitar-pop melodies are a long way from what Rivers had in mind when, at the age of 18, he left the ashram in Connecticut where he grew up and headed west.

“I moved out to LA with my heavy metal band,” he chuckles. “We were all about guitar technique and playing as fast as possible… and nobody cared at all!”

He’d been bitten by the rock band bug as a teenager – and it bit him hard.

“I remember I was in eighth grade when some of the other kids in class, they put together a band and they played Metal Health by Quiet Riot,” he recalls.

My heavy metal band were all about guitar technique and playing as fast as possible… and nobody cared at all!

“And I just couldn’t believe that kids my age were playing these real instruments and playing this song I loved… it just blew my mind! And so I got my own guitar shortly after that, and I started learning all the metal songs of the day.”

Indeed, metal provided the basis for Rivers’ guitar education – he idolised KISS and the Scorpions, but the biggest revelation came before he even picked up the instrument.

“When I was a kid I had seen other kids buy an electric guitar and amplifier… and it didn’t sound right – it didn’t have distortion!” he exclaims.

“I didn’t know that word ‘distortion’, but I knew there was something wrong, because it didn’t sound like the records I was listening to – it was all clean! And so before I got my own instrument, I learned what that term was – ‘distortion’!

“The other thing I learned was a ‘wah-wah bar’. And so whatever I did, I knew I had to get those two: distortion and a wah-wah bar!”

Death To False Metal

After turning up in LA with a metal band at the precise moment when everyone stopped caring about metal bands, a rethink was called for. From the start, Weezer were conceived to be the antithesis of hair-band excess.

“In the early years it was very intentional, very restrained,” Rivers recalls of his approach to songwriting.

“We were putting a lid on all of our technique, and trying to play as simply as possible – as if we’d just picked up our instruments the week before.”

Simplicity was key then, but part of the Weezer magic was always the way Rivers’ metal education added a unique vibe to these catchy pop-rock songs.

We were putting a lid on all of our technique, and trying to play as simply as possible

One such example is the saturated distorted rhythm guitar that has been a Weezer hallmark, from early moments such as No One Else or Getchoo, right through to more recent ear-grabbers Lonely Girl or Do You Wanna Get High?.

Tonehounds on online forums might spend thousands of words debating the precise recipe of his tone, but Rivers explanation is actually rather simple…

“Gear-wise, it’s not much of a secret – I just always make sure to turn the gain all the way up, so that it’s as distorted as possible,” he notes.

“But I do think there’s something in my fingers, and in the way I play, and the way I form the powerchords that is a little bit unique. Because sometimes I hear other people play through my gear, or I hear them play Weezer songs… and it doesn’t have that exact sound.”

I was very influenced by James Hetfield as a teenager – the way he plays rhythm

The idea that it’s all in the fingers is a well-worn and accurate guitar trope, but the player Rivers credits with inspiring his unique rhythm style is about as far from his shy, nerdy, bespectacled persona as you can imagine…

“I was in a Metallica covers band, and I was very influenced by James Hetfield as a teenager – the way he plays rhythm,” the guitarist reveals.

“It’s something deeper than [the tone], too – it’s something like an attitude, or a personality, or a spirit in him that comes out in these very subtle movements of his left and right hands. I think I really identified with that and really connected with that – and it comes out in my own playing.”

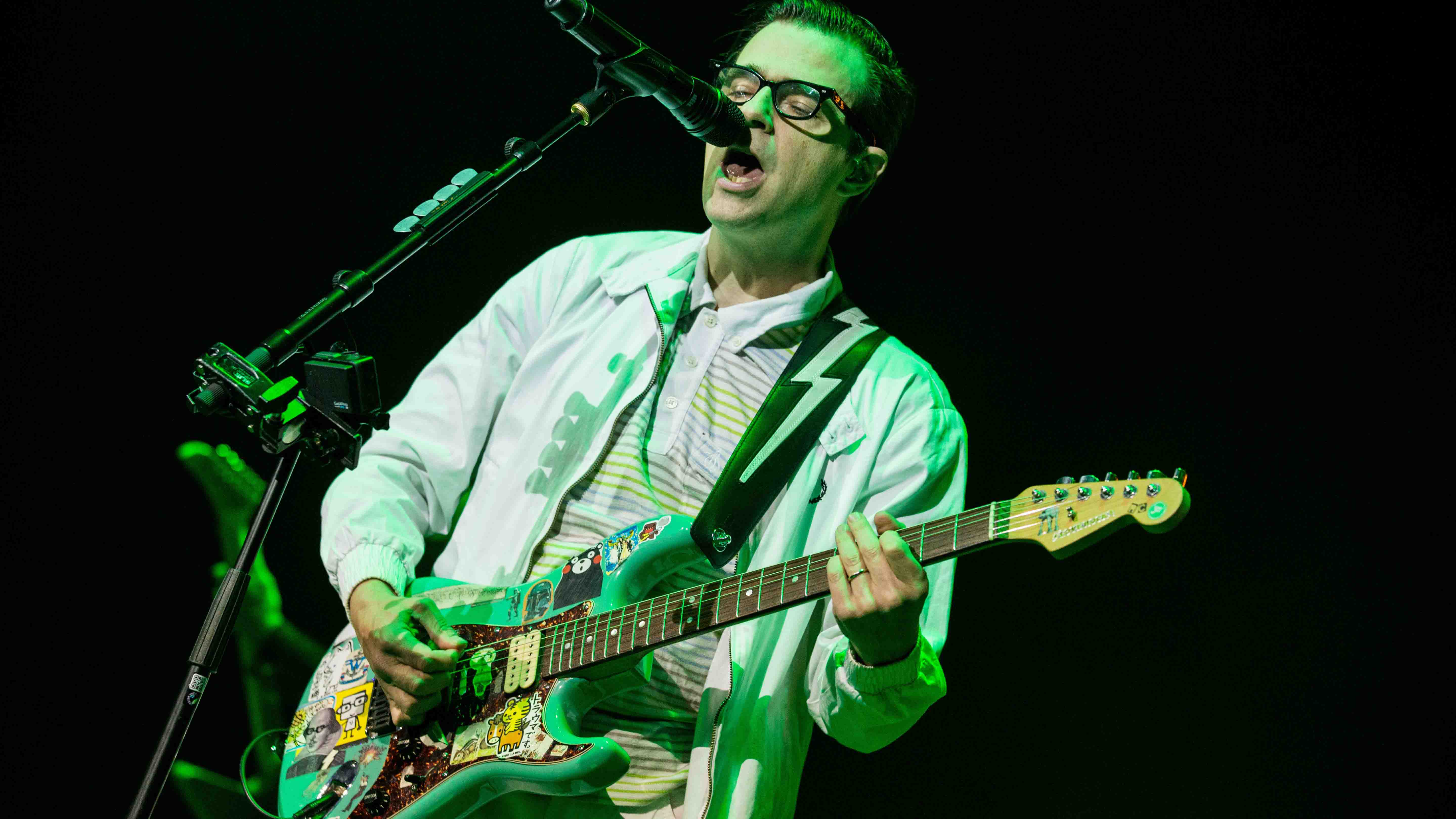

Rivers' runs

If Rivers’ tone is distinctive, his playing style truly sets him apart - it’s hard to think of another guitar player in the last two decades who has crafted quite so many memorable guitar hooks.

A quick listen to The White Album demonstrates that his knack for this is undiminished – Wind In Our Sails has more cool guitar beats in it than most bands can manage in a whole album – so how is he still doing it so consistently after more than 20 years?

The answer, says Rivers, is to put the guitar down altogether…

A lot of times for solos, what I’ll do is I’ll sing it, and then I go back and figure out how to play it on electric guitar

“A trick I have, is to write on different instruments – like I’ll write on the piano, and you end up with a different rhythm and feel to it, and a different kind of chord progression and bass line. But then I go back and play that on a chunky distorted guitar! And then a lot of times for solos, what I’ll do is I’ll sing it, and then I go back and figure out how to play it on electric guitar.”

Ah yes, the solos. If Rivers’ love of 80s metal is the constant background hum of Weezer, solo time is where he lets the shred out – burning up and down the fretboard in a flurry of hair metal-inspired notes that his guitar hero, KISS’s Ace Frehley, would be proud of.

What’s remarkable is not just the precision and technique Rivers displays in these moments, however, but how easy he makes it sound. It’s not by accident, either; it’s a philosophy.

“There’s a book called Effortless Mastery [by jazz pianist Kenny Werner] – it’s not just for guitar, it’s almost like a philosophical book about being a soloist – and that was a big influence on me,” he recalls.

“Like… the idea that when you’re up there on stage, it should be easy, it should be effortless. And that’s so different to how it was when I came up in the 80s, when it was about playing the most difficult thing possible.”

Pink Triangle

Reviews of the The White Album have drawn several comparisons to Pinkerton, Weezer’s unflinchingly honest and musically dark second album. Famously, Pinkerton was almost universally slated on its release in 1996, but has come to be regarded as one of the classics of the era, and a fan favourite.

If there are any comparisons to be drawn between it and The White Album, however, the man responsible isn’t going to make them.

“Um… no,” is Rivers’ curt response when we ask if he sees a link between the two. His curtness isn’t annoyance, however – his brain simply doesn’t work that way.

I don’t really think in historical terms; I’m just kinda living in the moment

“I don’t really think in historical terms; I’m just kinda living in the moment,” he explains. “I’m trying to come up with the next idea, so I don’t spend my time trying to build a 20-year narrative! [laughs]”

Rivers has no interest in canonising his past work because he’s much more concerned with keeping his songwriting approach fresh.

“Sometimes I’m mystified when people say that it sounds like a 90s record,” he observes.

“Take a song like LA Girlz, for example – which on the surface sounds like a 90s B-side like Suzanne. But if you take the lyric sheets and put them side by side, I think you’d be shocked at how different it is. LA Girlz is all very new techniques to me – cutting and pasting lines from different sources, and trying to suggest a story that never happened, and that’s very different from what I was doing in the 90s.”

This notion of “cutting and pasting” is very much at the heart of The White Album – and it’s a refreshingly unpretentious attitude to take when you’ve sold millions of records on the back of your songwriting genius…

“I’ve really got into it,” he reveals. “Going back through folders of hundreds of ideas and songs… and finding the very best bits and pasting them together, mixing and matching, seeing what happens. I just Frankenstein it all together, and sometimes it doesn’t work, and sometimes it does – but regardless you end up with the very best bits.

“I think it makes a huge difference overall on the record and I’m really excited about it. I do it with music, and I also do it with lyrics – I find great lines in my journals, and in books I read, and overheard conversations… and just paste them all together.”

The album’s bleak take on his prescription drug addiction, Do You Wanna Get High?, shows that he’s not entirely taking himself out of the songwriting equation – but there’s a balance to be struck when crafting songs as a married father of two in his mid-40s…

“I still draw on my personal experience a lot, but I’ll jumble it up and I’ll mix it with other things. If I were to write down my day-to-day life, it would make for a really dull album at this point,” he deadpans.

Take Control

In a world where so many guitarists are accumulate warehouses full of boutique and vintage equipment, Rivers displays a refreshing lack of gear fetishism – he uses what works, and as long as it keeps working, he sticks with it.

That’s true of his trademark custom Warmoth S-types, and it’s true of the guitar that provided the vast majority of The White Album’s tones – a P-90-loaded Gibson Les Paul Junior.

“For some reason that’s just the Weezer sound up in the studio,” Rivers shrugs of a guitar he’s been tied to on record since he used a pair of Les Paul Junior Specials to lay down much of The Blue Album all the way back in 1993.

If the sense of Weezer getting back to that classic 90s sounds seems at odds with Rivers’ stated desire to try new things, it’s the result of the relationship forged between the guitarist and The White Album’s producer, Jake Sinclair.

Jake [Sinclair] actually went out and found the very rare Mesa/Boogie amp that I used back in the early-mid 90s

“Jake is very much a fan of old-school Weezer,” Rivers explains.

“I think he’s the guy who’s always nudging me back to a more 90s classic Weezer sound. I’m just always coming up with ideas and trying to be creative, and so oftentimes I’ll veer away from where we started. And sometimes it’s cool… but sometimes it’s not… so he’s there’s to rein me back in!”

This ‘nudging’ applies to gear, too – so preoccupied was Sinclair with recapturing that early Weezer sound (“He’s obsessed with the past!”), he wanted to make sure the gear was just right, too, as Rivers explains…

“Jake actually went out and found the very rare Mesa/Boogie amp that I used back in the early-mid 90s – I think it’s called a Mk II or something [Weezerphiles believe it was actually a Mk I – Ed]. So yeah, he bought one of those and that’s what I used for the whole record!”

Blue is the warmest colour

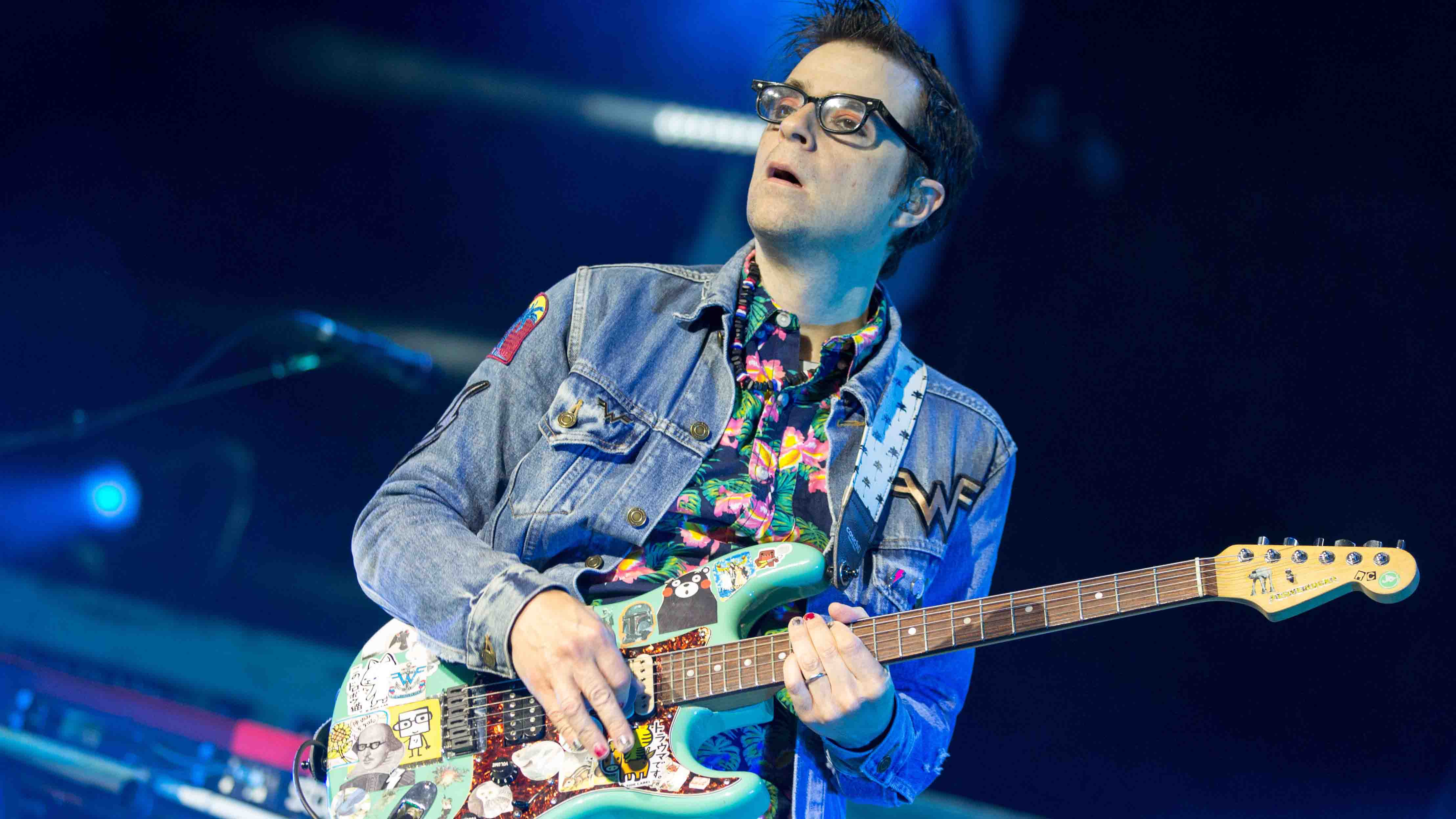

Shortly after Weezer finished recording The Blue Album, Rivers took delivery of a new guitar. The Sonic Blue S-type was put together from Warmoth custom parts, and was a unique beast.

Rivers spec’d Seymour Duncan Trembucker and DiMarzio Super Distortion II humbuckers, a monster hardtail bridge, and a built-in Black Ice passive distortion circuit in place of the tone control.

The ‘Blue Guitar’ was Rivers’ live weapon of choice between 1994 and 1997, when a huge crack on its body saw it retired. After this, several replacement Warmoth guitars were built, cannibalising Blue to create four new S-types that he’s used on and off for nearly two decades.

I have no allegiance to it at all, but it wins – every time

His favourite remains the new ‘Blue’ he started using in 2000 – “the Strat with the lightning strap” as he proclaimed in Back To The Shack. But as with all Rivers’ gear, his attachment isn’t about nostalgia – it’s just the best tool for the job.

“Every year or two I’ll do a blind test in the rehearsal room,” Rivers explains. “I’ll turn my back and have somebody else play a bunch of different guitars through my amp, so I can’t see what they’re playing. I rate all these different guitars… and every time that guitar wins for me! I have no allegiance to it at all, but it wins – every time.”

Don't Let Go

It’s a tired cliché to describe Rivers Cuomo as an ‘unlikely guitar hero’ – but there is truth that his personality and demeanour is in sharp contrast to the electricity that sparks from his fingers when he unleashes them on the fretboard. And perhaps that’s why the guitar still inspires him today…

“I don’t feel like I have any allegiance to an instrument or a style or a genre or anything – it just works for me!” he explains of his lifelong love affair with the instrument.

“For some reason, if I get up on stage without a guitar and I’m just singing over a track, or trying to do some other kind of music where there’s not a big electric guitar… it’s okay, but it just doesn’t feel right!

“I don’t know how to explain it more than that. But once I put my guitar back on and I start playing these big power chords it’s like, ‘Yes! This works!’ [laughs] Without the guitar I feel weak!”

Weezer’s self-titled 10th album is available now on Atlantic Records.