The Wrecking Crew: the inside story of LA's session giants

The Wrecking Crew: the inside story of LA's session giants

The Wrecking Crew: the inside story of LA's session giants

The Wrecking Crew: the inside story of LA's session giants

The Wrecking Crew: the inside story of LA's session giants

The Wrecking Crew: the inside story of LA's session giants

The Wrecking Crew: the inside story of LA's session giants

Throughout the 1960s, British bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones changed the face of music and defined the era (still are, in fact). In Detroit, the sound of Motown, led by The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson and The Jackson 5, had an equally seismic impact.

But on the West Coast, something different but no less significant was happening. The Beach Boys, Phil Spector and his 'Wall Of Sound,' The Monkees, The 5th Dimension, Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass, The Mamas & The Papas, The Association, and dozens more - all had massive, chart-topping hits, and the musicians that played on these smashes were a collective band of session aces called The Wrecking Crew.

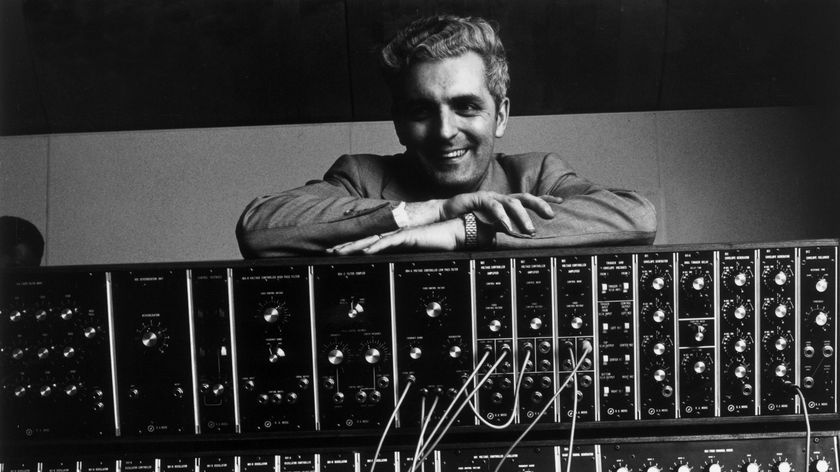

Like their Detroit counterparts, The Funk Brothers, whose intuitive instrumental talents fueled the hits of Motown, The Wrecking Crew operated in the shadows. Beyond the producers who hired them and the artists on whose recordings their playing appeared, nobody knew their names. They were faceless. If you were alive and listening to the radio during the '60s, you heard drummer Hal Blaine, guitarist Tommy Tedesco and bassist Carol Kaye all day long. But you never knew it.

"That's one of the real reasons why I had to make this film," says Denny Tedesco, son of the late Tommy Tedesco and director of the mesmerizing documentary, The Wrecking Crew. "Everybody knows this music by heart, but hardly anybody knows the people who played on the songs. You say Phil Spector or The Beach Boys to people, and they know who you're talking about. Say the names Hal Blaine, Tommy Tedesco, Carol Kaye, Plas Johnson, Al Casey, and they look at you like, 'Who?'"

Although a handful of Wrecking Crew members would break out and achieve solo fame (namely, guitarist Glen Campbell and pianists Leon Russell and Mac Rebennack [aka Dr John]), most of the players who comprised this illustrious (and highly paid for their time) collective - guitarists Barney Kessel, Howard Roberts and James Burton; keyboardists Al Delory, Larry Knechtel and Mike Melvoin; bassists Lyle Ritz, Ray Pohlman, Jimmy Bond and Red Callender; and drummers Earl Palmer and Jim Gordon, just to name a few - remained anonymous. Morning, noon and night, they sat in the studio, laying down parts that had the whole world's ear. (And not just on pop and rock recordings: the talents of these 'first call' players were used on TV theme songs, movie scores, advertising jingles - you name it.)

Tedesco completed The Wrecking Crew in 2008, but because of the enormous costs in securing the music to the documentary, he's been unable to find a distributor. So far, the only audiences who have been able to see the picture have been those attending various film festivals and private screenings.

MusicRadar spoke with Tedesco (whose father, Tommy, has been described as "the most recorded guitarist in history") about the making of the film. In addition, we discussed the inner workings of the group, some of the notable producers they recorded with and what it took to hang in what Tedesco describes as "a fun, creative but extremely intense musical pressure cooker."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What's been the problem with getting the film distributed? Is it solely a music rights issue?

"It's a matter of finances, but they're kind of tied into the music rights thing. I remember when I was making the picture, I'd go to people with this nice 14-minute segment I had. It looked beautiful, all of it was shot on film. Everybody loved it and said, 'That's great, we'd love to see more.' And I'd explain that I was trying to raise money to finish. People were very discouraging: 'Oh, you'll never finish it because you'll never be able to get the labels and publishers to come together.' But I wasn't about to just quit. It was too personal. And by that time, I was too far into it, both emotionally and financially.

"Basically, I did what you're not supposed to do: I maxed out the credit cards, refinanced, paid off the credit cards, and I kept going. [laughs] I borrowed money in order to make a cut of the completed film, which allowed me to get it into some film festivals. Once we got into the festivals, it won all of these awards, everybody loved it - I thought we were finally ready to get a distribution deal.

"Two problems, though: First problem was, this was in 2008, when everybody went bankrupt. Second problem was, the film had that one word attached to it that nobody wants to hear when you're trying to find money: 'documentary.' Put the word 'music' in front of 'documentary' and that really tends to scare people.

"To try to make the film more appealing to distributors, I had to go back to the labels and publishers and renegotiate the price for the music. I was able to get it all down to $300,000, which is still a lot. With most documentaries, that's their entire budget, so I have a sizable price tag on my movie, and it's all because of the music."

But the music is key to The Wrecking Crew. Without the music, you don't have a picture.

"Exactly. [laughs] It's very frustrating. I'm sitting on this wonderful film that people love. Not being able to have it seen properly, to get a real distribution deal, it's been tough, a real struggle."

So for the past few years, you've been showing it at festivals and holding your own screenings.

"That's right. Basically, we work through the International Documentary Association, and which allows us to screen the film and take donations, which we then use to pay off the labels and publishers as we go along. Today, in fact, I just wrote a check for $5000. I love paying down that debt! [laughs] Each time I make a payment, I feel such a weight off my shoulders."

When do you start making the film?

"My father got sick in 1995, and I knew he didn't have much time left - he died in '97 - so I started putting the film together around 1996. I thought it was very important to get as much of his story in his own words as I could. But the film isn't just about my father, of course; it's about all the people in The Wrecking Crew. I thought the process of getting it out there was going to be a pretty quick one. Shows you how much I know. Fifteen years later, I'm still trying to get the film seen."

We love the roundtable interview segments. After so many years, the musicians still seem like they're part of a gang.

"Yeah, that was great to do. There's my father, and then there's Carol Kaye, Hal Blaine and [saxophonist] Plas Johnson. We were supposed to have Earl Palmer, as well, but he got sick and couldn't make it. There is camaraderie amongst the players, but it's not always a love-fest. It's like brothers who fight sometimes - or, in Carol Kaye's case, a sister. In those scenes, I look at them as a quartet without their instruments. The way they banter and play off of one another - it's like they're making music."

When did your dad become part of the Crew?

"It was in the late '50s. By the time I was born, in 1961, The Wrecking Crew - even though they weren't called that at the time; they weren't even called that during their career - were already very well established. It's funny: My father was always so worried that he'd be struggling his whole life. Then, one day in the mid-'60s, he looked at his bank account and he couldn't believe it: 'Hey, I'm not struggling. I've got money in the bank!' For a musician, that was an unbelievable feeling.

"There's a great line in the movie that kind of sums it all up. It's when [guitarist] Al Casey says, 'You couldn't tell how busy you were by the amount of work you took. It was the work you turned down.' The musicians in The Wrecking Crew worked real hard. I know my dad was constantly booked, constantly on call. He had his little black book, and he was always writing a session in, trying to fit in everything he could."

Tommy Tedesco and Carol Kaye work on another Top 10 smash. © Hal Blaine

What was the secret to the players' musical chemistry? They worked together so much, but they didn't have a set, recognizable sound. They were chameleons, able to adapt to any song or artist.

"That's what's so interesting about part of the problems I've had with the film. People have said, 'Well, why don't you just cut it down to 20 songs?' And I said, 'I can't. You don't realize how many huge records these people have played on. We're talkin' hundreds and thousands of songs!' You could do a film about Motown in 20 songs; you could do a film about Muscle Shoals in 20 songs. The Wrecking Crew? That's more than 20 songs.

"They were definitely chameleons. They would do a Frank Sinatra session, then go right into working with The 5th Dimension or The Mamas & The Papas or The Chipmunks - all in a single day! Or they'd do a movie score or TV commercials, and then they'd play with Brian Wilson or Phil Spector. I can't think of many musicians who had that same level of versatility."

Was there one single producer who you'd credit with assembling the group?

"They were working with a lot of different people, but I say Phil Spector pretty much corralled the main bunch of people who would form the nucleus of The Wrecking Crew. After they recorded with Phil, everybody in town wanted them. Brian Wilson certainly made use of them on a lot of Beach Boys sessions, but he really only started working with them after he heard what they did with Phil."

Speed and versatility were two of the group's biggest calling cards. But what was it like when they worked with some well-known perfectionists, such as Phil Spector and Brian Wilson?

"That's a good question. I think they all treated these sessions as work, and because they were getting union fees, they were quite happy to put in the hours, no matter how long something took. Some sessions were over boom, boom, boom. Others would take days and longer, particularly when you're talking about Phil Spector or what Brian Wilson started doing, the concept albums and all that.

"Phil could get under certain people's skin. My dad was fine with him, but [guitarist] Howard Roberts walked out on a session. My dad, I know, if you wanted him to strum that same chord all day, he'd gladly do it. He was an artist, and he liked to be creative, but he looked at it like, 'Hey, I'm paying off the car. I'm paying off the house.'

"I think the only time that my father ever got into it with a producer was with Sonny Bono. It had nothing to do with the music, it was all about money. Sonny was working with Cher at this point, and he wanted my dad to work for $20 a song. My dad said no. He said, 'I'll work for $20 an hour, but you're not getting a flat rate out of me.' Sonny wanted my dad, so he agreed. I remember my dad telling me that the other guitarist next to him had agreed to $20 for the song, so my father walked out of that session with a lot more money in his pocket."

Hal Blaine, who provided the main beat behind The Wrecking Crew. He also gave the group their name. © Hal Blaine

From what you understand, was the term 'Wall Of Sound' ever tossed around during Phil Spector sessions?

"I'm not sure. I asked that same thing of Ronnie Spector, and she wasn't sure. She didn't even know when she first heard it used - one day it was just kind of there. Like the term 'Wrecking Crew,' I think 'Wall Of Sound' might have been after the fact. Put it this way: my dad never said, 'Oh, I've got a Wall Of Sound session today.'"

You spoke of the Crew's camaraderie being akin to that of siblings. But was there ever competition? Were they ever jealousies if one player got a call that the other one might have wanted?

"I think it was a friendly competition, and there might have been a bit of one upsmanship at times. People never took things too far, though. They couldn't: If you were an asshole, nobody would call you. Nobody wants to work with a jerk. When the Crew were doing sessions, they had to stay cool and professional.

"They helped each other out, too. If one guy couldn't make a session, he'd recommend somebody else for the gig - and, of course, he'd hope and expect the favor to be returned. So it was a weird blend of friendly competition.

"When there was tons of work during the '60s, everybody was pretty happy. It was only when things started slowing down towards the end of the decade and into the '70s, that's when people started getting a little nervous, a little testy, and some of the friendships became strained.

"One really has to appreciate how calm and collected everybody was to be a part of such a team and survive in the situations they were in. Glen Campbell said it really well: 'It's one thing to play with Michael Jordan, but it's another thing to play with a whole roomful of Michael Jordans.' Because everybody in that room brought their A game all the time. They had to do three or four songs in three or four hours. If you couldn't nail it, you weren't gonna last."

There's so many players to talk about, but we want to ask you about Carol Kaye. How did she manage to break into - and thrive in - what was essentially a boys' club?

"It is pretty mind-blowing when you think about what she accomplished. But the main thing is, she wasn't in that room because she was somebody's girlfriend or wife; she was there because she was a fabulous bass player. The foundation of any great band and any great recording is the rhythm section. If Carol Kaye didn't do what she did beautifully and perfectly, she wouldn't have lasted a day.

"I don't think the guys in The Wrecking Crew even talk about her as a woman. I mean, they have opinions about her [laughs]… and she has opinions about them. But the bottom line is, she was a musician first. She was just so phenomenally talented."

Sharp-dressed men: guitarist Glen Campbell hangs in the studio with Blaine. © Hal Blaine

During the '60s, the drug scene exploded. How did this affect The Wrecking Crew? We can't imagine them playing so many sessions day and night while being messed up.

"They weren't. Coffee and cigarettes were the two big things. I'm not saying there wasn't some stuff happening here and there, and probably most drug use was going on behind the other side of the studio glass, in the control room. My father, I know, stayed away from drugs simply because he didn't like the feeling of being out of control.

"It was a very tight, professional vibe. Sure, people liked to kick back, and it was the '60s and all that, but the work had to get done. If you were late for a gig, you just killed your career. It wasn't like a real band where you could go, 'Oh, the singer's high, we'll just tolerate it.' These were people working for hire. The last thing you wanted was to have an orchestra waiting around for you. Believe me, word got around fast. 'So-and-so can't play. So-and-so was late.' If talk went around, your phone wouldn't ring."

As we find out in the film, The Wrecking Crew played on records that were credited to various bands. Did any members of these bands get resentful?

"Hal said that the drummer for The Byrds got pissed off. [The Wrecking Crew backed up Roger McGuinn on Mr Tambourine Man.] Other than that, I don't think so. Well, The Association got upset a little, too. It was because their producer told them, 'If you want me to do your record, I have to have these guys in the studio' - meaning the Crew. Then he said that he was going to list them on the album as players, and The Association thought that was going too far."

A few of the players broke out and became stars in their own right - Leon Russell, Dr John, Glen Campbell. How did that sit with the other folks in the group?

"There was never any bruised egos or resentment. In fact, I think everybody was extremely proud of those guys and would cheerlead them on. I remember my father even tried to produce an album for Leon Russell on which Leon was going to play the guitar. It didn't work out in the end, though, because guitar just wasn't Leon's instrument."

Your father grew up playing classical and jazz. How did he feel about playing pop and rock music during the '60s and '70s? Did he enjoy it?

"No. [laughs] No, not really. He loved playing the guitar, and he couldn't believe he was making a great living at it. He came from Niagara Falls, New York, and he used to think that he'd never leave there and would wind up working in a factory. So he worked very hard at the guitar, and when he became successful he would always say, 'I am the luckiest man in the world.' No, he was never a huge rock fan, but he was great at pretending. [laughs]

"He and the rest of the Crew might have looked down at some of the things they were playing, but they kept it to themselves. They never sat there during sessions and said, 'This is so beneath me.' And I think my dad had respect for producers or songwriters if a song was well crafted.

"They were pros. They didn't have to like something to make it great. They could play better than anyone, play more types of music than anyone, and they were always there to give 110 percent. It didn't matter if you were Frank Sinatra or the kid next door making his first record. If you were paying them, they were there to help make your record a hit. And that's what they did over and over and over again."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

Most Popular