The making of Metallica's Master Of Puppets

Behind the scenes of James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett's metal masterpiece

Introduction: obey your master

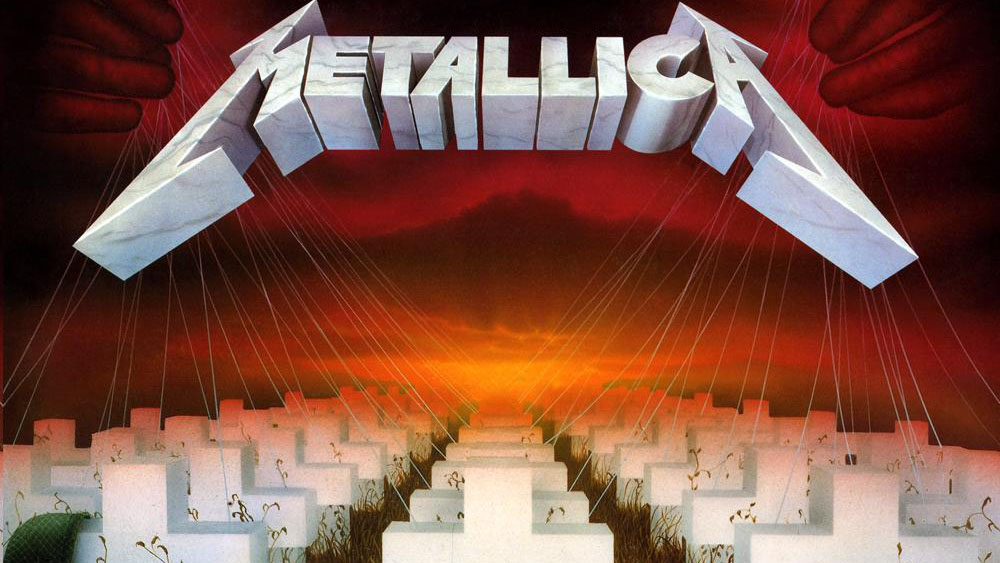

Gravestones. Hundreds of them. Rising from the rotten grass, bedecked with the kit of fallen soldiers, each one with a thin silk line rising to a pair of bloody hands in the scorched skies. It was the kind of sleeve that stopped you in your tracks, but then Master Of Puppets was the kind of album that made time stand still.

The statistics, as they might be viewed by a record label bean-counter, don’t do it justice. Sure, Puppets was enormous, but Metallica would make bigger albums. The point is, they never made a better one.

This third record is a line in the sand between the gutter and the stadiums, and, if we’re honest, the reason we kept faith during the double-dip of Load and ReLoad, tolerated the hook-ups with the orchestras and squinted for greatness in St Anger.

It’s the connoisseur’s choice: the perfect mix of poise and fury, with the best songs from the band’s greatest line-up. Lars Ulrich might have been the quotable mouthpiece and Cliff Burton the classically trained whizz, but when it came to Master Of Puppets, it was James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett who were pulling the strings.

Don't Miss

Kirk Hammett and David Karon talk KHDK guitar pedals

Kirk Hammett on Metallica's Kill 'Em All

Robert Trujillo talks Jaco Pastorius, film-making and fingers

The thing that should not be?

Before Master Of Puppets, Metallica were a joke. A good joke, perhaps, but certainly not a band to be mentioned in the same sentence as ‘world domination’.

Two albums had put the quartet on the radar and club circuit, and now they gurned from the foothills of the rock press – all spots, vests, denim and hair like wet straw. They were a mash-up of every hateful quality of the mall-rats in their San Francisco headquarters. For now, Metallica were not iconic, they were just moronic.

At their best, the four musicians had obvious talent, with 1983’s Kill ’Em All and 1984’s Ride The Lightning home to such classics as Seek And Destroy and Creeping Death. Nobody expected these songs to infiltrate the 80s mainstream, though, not least the band themselves, whose ambition appeared to stretch little further than living up to their nickname, Alcoholica. “We don’t mind you throwing shit up at the stage,” announced Hetfield at one show. “Just don’t hit our beers – they’re our fuel, man!”

To anyone who witnessed the post-show carnage, this was a band with permanent double vision. In fact, Metallica had their bloodshot eyes clearly on the prize, and by 1985, they were musically telepathic and ready to be taken seriously. “We were honing it on Lightning,” noted Ulrich, “and Puppets came the closest to a bullseye for that type of stuff.”

Big ideas

In hindsight, all the signs were there that Metallica were readying a grand statement. In contrast to the few days taken to bang out Kill ’Em All on a shoestring, Hetfield and Ulrich had crossed continents in search of the perfect studio, before familiarity and economics saw them return to Copenhagen’s Sweet Silence with Ride The Lightning producer Flemming Rasmussen.

Even more telling of the band’s broadening horizons was an apparent desire to create art, not noise. Where before Hetfield had screamed himself hoarse on vague themes, Master Of Puppets had a concept – “manipulation in all its forms,” was how Hammett saw it – and songs with sentiments, from the battlefield hell of Disposable Heroes to the broken ruminations of an asylum patient on Welcome Home (Sanitarium). “The idea for that came from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest,” Hetfield told Guitar World, and combined with Hammett’s arpeggiated minor add9 intro, the result was deeply unsettling.

Lyrics were one thing; the real evolution was the way Metallica were now approaching their music. No longer were riffs tossed off like vodka shots. With sessions starting in September ’85, Puppets was their first record to be truly crafted, painstakingly assembled over five months. Hardly a lifetime by Axl Rose standards, until you considered that the music had been ready for months. “The only two songs that weren’t finished were Orion and The Thing That Should Not Be,” Hammett told Guitar World.

James is the best rhythm guitar player in the world by a mile

So the time was not spent on writing but on honing, with Metallica chasing down their signature brick-wall tone and squeezing every last drop of juice from the mixing desk. One song might feature up to 52 tracks, though it’s not always apparent, with Hetfield’s surgical precision letting him stack left, right and central rhythms that always sound airtight (some songs have more, while Battery and Damage, Inc sounded “a bit muddy”, and only have two).

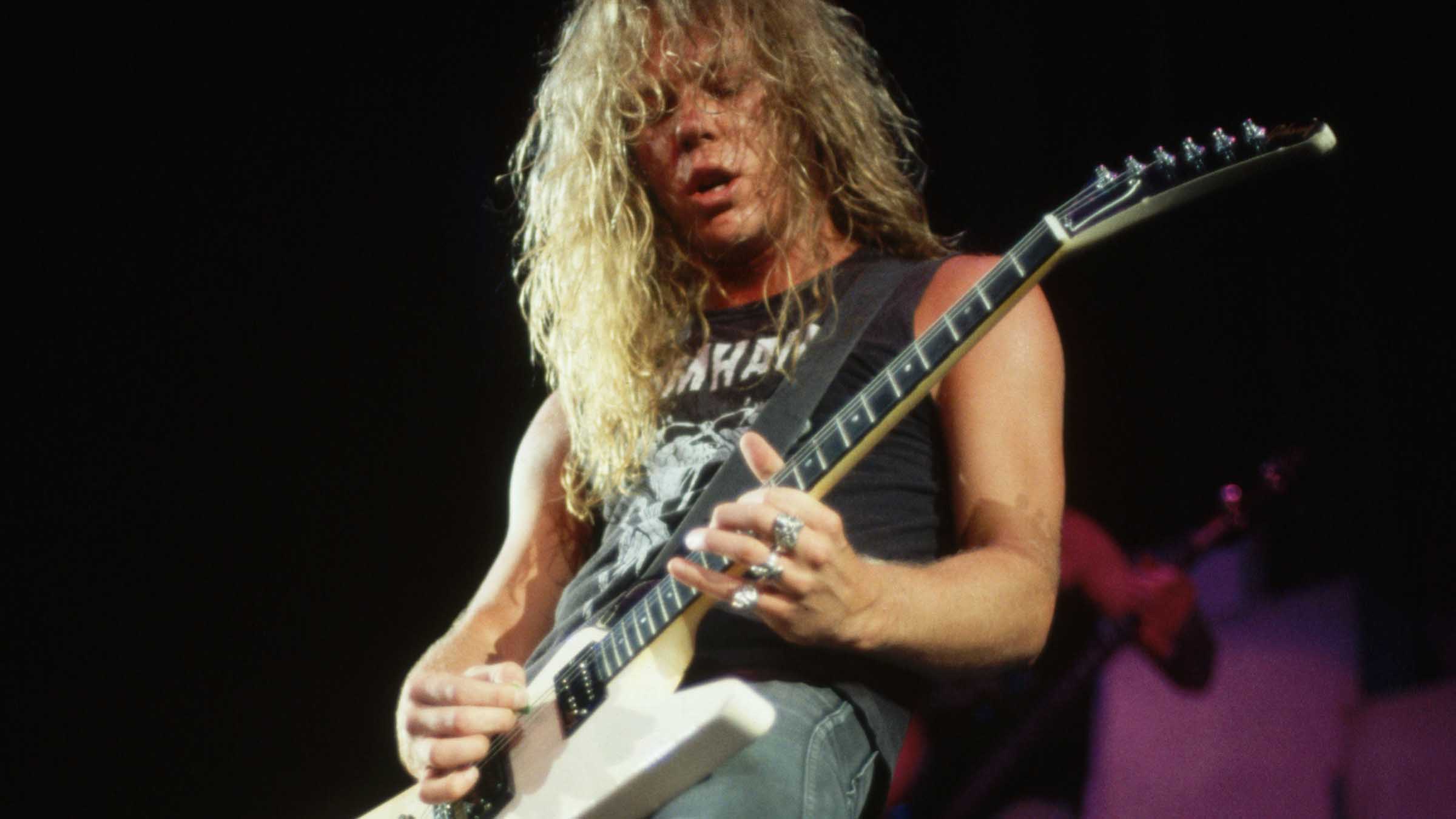

“James is extremely exact,” Rasmussen told Metallica biographer Joel McIver. “He’s the best rhythm guitar player in the world by a mile. There’s no-one better than him when it comes to downpicking. It’s unbelievable. He’ll do eight tracks and it’ll sound like one guitar.”

Beyond thrash

Rock encyclopaedias concur that Metallica are a ‘thrash band’. Maybe so on full-throttle moments like Disposable Heroes and Damage, Inc, but spin Puppets next to, say, Slayer’s Reign In Blood, and you’ll find the former is far more melodious and experimental. Sometimes too much, felt the band.

“We felt inadequate as musicians and as songwriters,” Ulrich told McIver. “That made us go too far, around Master Of Puppets… in the direction of trying to prove ourselves: ‘we’ll do all this weird-ass shit sideways to prove that we are capable musicians and songwriters.’”

With respect, he’s wrong. It’s precisely this light and shade that keeps Puppets fresh while lesser thrash albums blur into a sea of galloping riffs. Take Battery: an opener that has the balls to start with weaving flamenco guitars, one laying down a four-chord bed in which the bass note rises by a semitone each change, before harmonised electrics swing in like a wrecking ball.

“The idea to make the intro to Battery so big evolved in the studio,” Rasmussen said. “There are tons of guitars on there and we just kept tracking.”

Battery is heavy as hell, but strangely light on its feet, with the time signature dodging between 4/4 and 5/4. And by the time Hammett had blazed a warp-speed legato solo in E minor, the tune had practically cracked the Earth’s crust. There’s no time to recover.

Without breath, Battery gives birth to the jaw-breaking title track, an anti-drug song that ironically sounds like a bad trip. Master Of Puppets is a guitarist’s paradise. First, there’s the doomy bedrock of thrash rhythms, played in E and F# using downstrokes, and made brilliantly hectic by Hetfield’s calling card of stabbing three notes ‘across’ the beat. “The riff was pretty messy,” he said, modestly, in Guitar World. “Constantly moving.”

[We were] trying to prove ourselves: ‘we’ll do all this weird-ass shit sideways to prove that we are capable musicians and songwriters’

But then, just as you have the song’s card marked, it throws a curveball with the love-it-

or-hate mellow section in which Hammett strokes out a sublime minor key solo, followed by the truly creepy ending, which has backwards guitar parts swimming through the mix.

“To get them I played a bunch of guitar parts that were in the same key as the song and laid them down on quarter-inch tape,” Hammett told Guitar World. “Then we flipped the tape over and edited it, so we had two or three minutes of backward guitar. We put it in the last verse.”

Puppets is a schizophrenic masterpiece, a song so good you’ll even forgive Hammett for fluffing a note in the first solo, where he pulls the E string clean off the fretboard of his Jackson Randy Rhoads V. It’s the only mistake that made the cut. “We heard it back, and I was like, ‘That’s brilliant! We’ve gotta keep that!’ Of course, I’ve never been able to reproduce that since.”

Classical heroes

Disposable Heroes is even better. Arguably the album’s peak, it’s built on the telepathy of Hetfield’s super-tight Eb riffing and barked sergeant major vocals (“back to the front!”), and the oddball end-of-verse Hammett swells that, bizarrely, were inspired by attempting to mimic the bagpipes in old war movies.

Equally unlikely is Damage, Inc, a heads-down thrash juggernaut with an intro inspired by a long-dead German composer.

“I was into the whole Euro-metal thing,” Hammett told McIver, “and I used a few different scales. The Phrygian Dominant was the one that Cliff showed a lot of interest in. He used to watch me playing lead, trying to learn guitar licks and trying to snag bits and pieces of information. We would talk about theory and how it worked, just casual conversations about it.

Cliff told me that the intro to Damage, Inc is actually based on a Bach piece

“He loved theory and he loved classical music. He was a big fan of Bach. He told me that the intro to Damage, Inc is actually based on a Bach piece called Come Sweet Death, which was a little bit ironic in the wake of what would happen to him [Burton was killed in late 1986 when the Metallica tourbus overturned in Sweden].”

Masters of circuits

Respect to Rasmussen, and to the 20 fingers of Hammett and Hetfield, but let’s not forget the vital importance of gear in the Puppets sound. These were the years before the ESP signature models and active pickups, but there’s a case that the pair’s tone has never been more savage.

For much of this album, Hetfield was playing his iconic white Gibson Explorer (the standard ceramic humbuckers were replaced with EMG 81s in 1987), while the absurdly heavy The Thing That Should Not Be saw him turn to a Jackson KV1 and down-tune for the first time.

His watertight distortion was achieved not with FX – “the last time I used a distortion pedal was on Ride The Lightning,” he noted in 1992, “and it was hell!” – but from the molotov cocktail of a Mesa/Boogie Mark II C+ rewired as a preamp, and a 100-watt Marshall power amp with 4x12 cabs.

On lead, Hammett was more relaxed about effects, favouring an Ibanez Tube Screamer and a Dunlop Cry Baby, and fell back on his old axes, including a Gibson Flying V (either ’74 or ’78) and a Fernandes Strat copy with a Floyd Rose.

Like Hetfield, he was also in thrall to the fusion of Mesa and Marshall. “Boogie made those heads for a short time in the mid 80s,” he told Guitar World. “There’s something about Boogie Mark II C heads that was really unique and very individual in their gain stages and sound. Most of Master Of Puppets was tracked with Boogie heads and Marshall heads combined.”

The memory remains

If the gear setup was slim by modern standards, then the promotional campaign for Master Of Puppets was positively emaciated. There were no hit singles to reel in radio listeners. No music videos to offer the nascent MTV.

It’s hard to believe it now, but Puppets never actually climbed any higher than No 29 and No 41 on the US and UK charts. Yet the band stood strong by their creation. “I remember thinking, ‘Wow, this is a fucking great album’,” Hammett reflects. “‘Even if it doesn’t sell anything, it doesn’t matter to me because this is such a great musical statement.’”

But the boulder was rolling. Puppets started selling and never stopped, riding a word-of-mouth buzz that grew louder as Metallica crossed America on a six-month Ozzy Osbourne tour shortly after the album’s release. By 2003, it had shifted six million units. Not bad for an album that was troubled, awkward and divisively brutal.

“Maybe Master Of Puppets was the record that a lot of the early fans identified with,” Hetfield told McIver. “There’s still an innocence about it and just a real ‘fuck you, world’ attitude to it.”

So Metallica had it all. The album of their careers. A legendary line-up firing on all cylinders. An adoring fanbase and an international market with its jugular exposed. For this one-time ragbag of no-hopers, everything was working out. Then the tour bus pulled away on the Damage, Inc Tour, towards the fateful stretch of motorway north of Ljungby, Sweden, and it became clear that some higher puppet-master had other ideas…

Don't Miss

Kirk Hammett and David Karon talk KHDK guitar pedals

Kirk Hammett on Metallica's Kill 'Em All

Robert Trujillo talks Jaco Pastorius, film-making and fingers