The evolution of the guitar riff

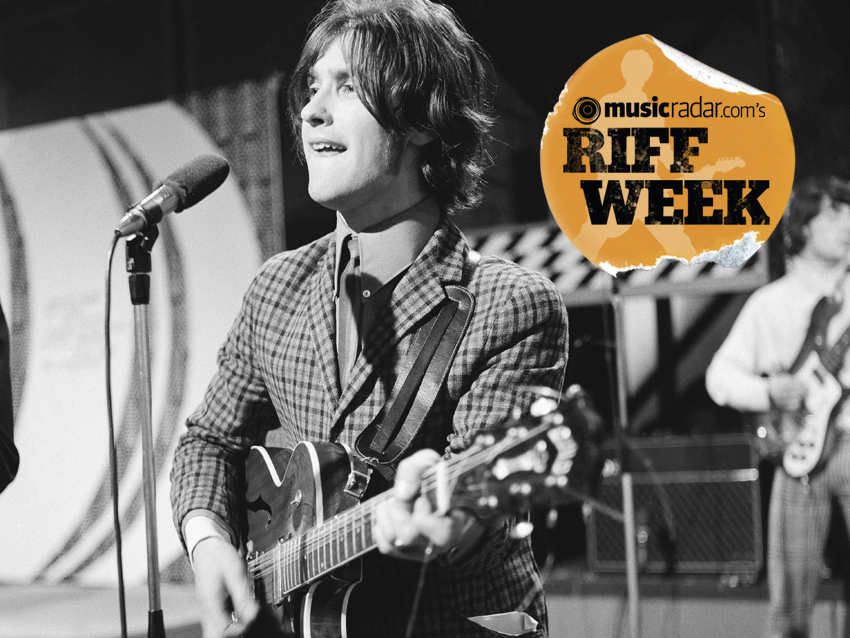

Dave Davies of The Kinks: riff pioneer

© Michael Ochs Archives/Corbis

In the beginning there were the blues and the blues were, well - in their purest form - little more than guitar riffs: simple licks repeated over and over. But it was upon these solid foundation stones that rock 'n' roll's glittering palace would be built.

In terms of evolution, '50s blues tracks like Muddy Waters' Hoochie Coochie Man and Howlin' Wolf's Smokestack Lightning represent rock's pre-Cambrian age. No chord changes - just a simple, direct message to the heart and soul. Some say they've never been bettered.

"Soon enough, rock 'n' roll would add rhythm to the blues and the result was a cultural explosion that changed everything"

Soon enough though, rock 'n' roll would add rhythm to the blues and the result was a cultural explosion that changed everything. Tempos increased; song construction grew more complex. Among the pioneers who mapped out this new frontier was Chuck Berry, who transferred what were effectively boogie woogie piano lines to his Gibson guitar. His use of double-string licks added a sophistication that would be a huge influence on successive generations of guitarists.

But even at this early stage there was a reaction, a yearning to return rock to its simplest state. Take Link Wray, whose 1958 record Rumble was based around a riff containing a mere three notes. Darker and more menacing than anything else around at the time, Rumble remains the only instrumental record to be slapped a broadcasting ban, its riff so dangerous the radio listeners of the late '50s had to be shielded from its bad-assed scowl.

Bad-assed scowling, however, was largely off the agenda in the early '60s. Whilst the Beatles tended not to write songs around riffs (at least not until Day Tripper), their long-haired rivals, The Rolling Stones, based most of their initial songwriting efforts around sped-up blues licks. Their first UK number one, The Last Time, is almost entirely a curling Chuck Berry riff.

But it is Satisfaction that remains their first claim to riff immortality. The story goes that Keith originally envisaged it on a horn section and only played it through his Gibson fuzzbox for guide purposes. Jaws consequently dropped and the rest of the band proclaimed the song as good as complete.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Even before that, another British band had laid down a marker in the development of the riff. You Really Got Me is nothing more than a two-chord phrase repeated with rough distortion, provided when Dave Davies reputedly sliced the speaker cone of his amp. It would be a trick Davies would repeat on All Day And All Of The Night before he and his brother Ray set sail for more refined musical waters.

Complicating matters

Ground-breaking riff-writers they certainly were, but this British crop of mid '60s guitarists - Davies, Richards, Townsend, Clapton - would eventually find themselves put in the shade by the arrival of American Jimi Hendrix. As well as bringing an unheard of showmanship, Hendrix broadened the potential of the instrument like nobody before or since.

Next page: From Hendrix to Hetfield

In step with rock's expanding horizons, Hendrix's riffs were more elaborate than their predecessors - also making full (and pioneering) use of the new pedals and effects that rock guitarists now had at their disposal, including wah-wah, rotary cabinets, delay and fuzz.

It's at this point that rock split, for the first time, between those who saw it as a form that should progress - using ever-more ambitious arrangements - and those who espoused the back-to-basics ethos of the blues revival and the beginnings of what would become known as heavy metal. Black Sabbath and Deep Purple were two prominent names in this later development, with Sabbath's Tony Iommi breaking new ground by detuning his guitar and coming up with a succession of distorted riffs heavier than anything before them.

It was another new genre, punk, that further put paid to any trend towards increasing complexity, and while most punk bands took a dim view of riff-based music, that's not to say the era didn't see any memorable punk riffs at all. The Sex Pistols' God Save The Queen and Holidays In The Sun could easily have been played by Chuck Berry, though, of course, Steve Jones's guitar was heavily distorted and fattened with effects.

"Rock split between those who thought the riff should progress and those who espoused the back-to-basics ethos of the blues revival and the beginnings of what would become known as heavy metal"

The post-punk generation took the rock re-think even further, emphasising other instruments such as bass and percussion and often demoting the guitar from the foreground. The major innovations of this era were the choppy, spiky riffs bands like Gang Of Four used, where Andy Gill's guitar is often used more as a percussive rather than a lead instrument.

But while the post-punkers were re-inventing the wheel, heavy rock was going through a renaissance. Nearly all of AC/DC's most memorable songs of this period are based around Angus Young's brutal power riffs. Again, the likes of Back In Black and Hells Bells are simply old rock 'n' roll riffs, but slowed down and simplified for maximum effect.

If AC/DC were refining their back to basics approach, their cousins in the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal groups - Iron Maiden, Def Leppard, Judas Priest et al - were rediscovering the joys of the fret-abuse. This reached its apotheosis with the rise of Metallica in the mid '80s. Based around the fast intricate riffing of James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett, Metallica rebooted metal music for a new era.

Next page: A retrenchment and into the '90s...

Metallica's main rivals as kings of thrash were groups like Slayer and Megadeth, both of whom would take riffing to dizzying new levels of intricacy as the decade progressed. Meanwhile, Pantera were, by the late '80s, developing their own 'groove metal' sound, based around guitarist Dimebag Darrell's relentless churning riffs.

These groups' musical innovations were also being noted elsewhere. It's not insignificant that one of Slayer's impossibly elaborate riffs from Angel Of Death was sampled by hip hop legends Public Enemy on their classic She Watch Channel Zero.

Into the '90s

After every technical advancement, there is - by necessity - a period of retrenchment. If grunge drew much of its moral indignation from the same place as punk, its most famous riffs were direct throwbacks to pre-punk 'classic' rock. Pearl Jam and Soundgarden were clearly inspired by Black Sabbath's Iommi and his penchant for distorted heavy riffs. Meanwhile, Nirvana's anthem-for-a-generation Smells Like Teen Spirit infamously nicked part of its central figure from Boston's 1977 hit More Than A Feeling.

"If grunge drew much of its moral indignation from the same place as punk, its most famous riffs were direct throwbacks to pre-punk 'classic' rock"

Parallel to the development of grunge, the disparate collection of individuals who made up Faith No More were peddling their own take on the riff's place in rock. FNM guitarist Jim Martin was an old school rocker who used classic rock-influenced riffs on tracks like Epic and A Small Victory. Yet the band's incorporation of funk rhythms would have a huge influence on the next wave of rock: nu metal.

The guitarists in the biggest nu metal bands - Korn, Linkin Park and Limp Bizkit -used their instrument in a more rhythmic capacity than any genre before, supporting the bass and drums. What memorable riffs there were from the era were often little more than a few notes or single power chords.

But nu-metal's day went as quickly as it came and this last decade has seen the rock world splinter even further. Arguably the most memorable riffs of the Noughties have been remarkably simple, such as Queens Of The Stone Age's No One Knows or the White Stripes' Seven Nation Army - the latter being possibly the only riff in history that has ended up as a football chant.

And perhaps therein lies the paradox. Fifty years after the dawn of rock 'n' roll and for all the multiple musical innovations and developments over the years, it seems that it's the simpler stuff that has best stood the test of time.

Riffs like Satisfaction, Smoke On The Water, Paranoid and the like all stand defiantly un-evolved, a direct link back to rock 'n' roll's primal glory. But then growing up has never been what rock 'n' roll has done best. Is it any coincidence that one of the greatest living exponents of the guitar riff is a 54 year old man who wears a school uniform? Who needs fifteen notes when you can express yourself clearly and succinctly in just three?

Will Simpson is a freelance music expert whose work has appeared in Classic Rock, Classic Pop, Guitarist and Total Guitar magazine. He is the author of 'Freedom Through Football: Inside Britain's Most Intrepid Sports Club' and his second book 'An American Cricket Odyssey' is due out in 2025.