Steve Vai discusses the Vai Academy Song Evolution Camp

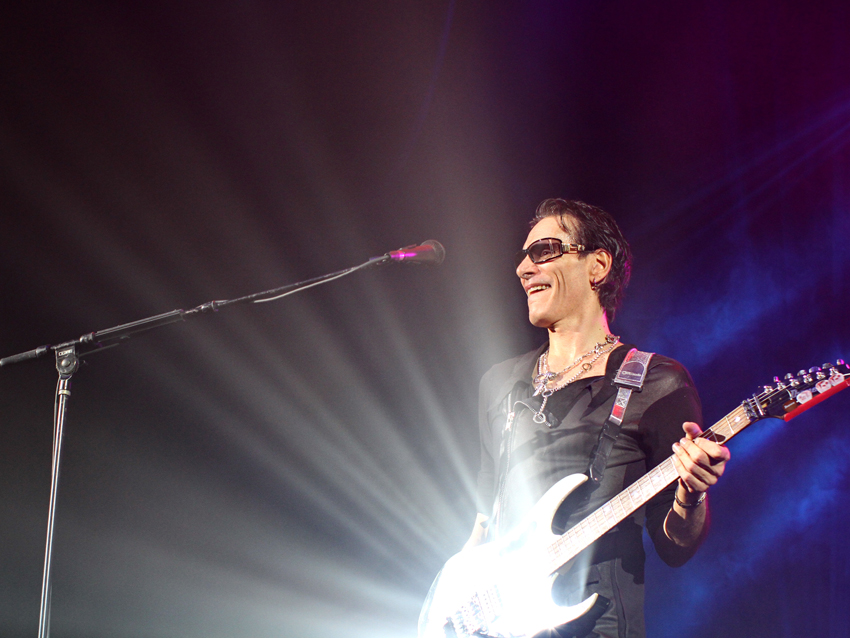

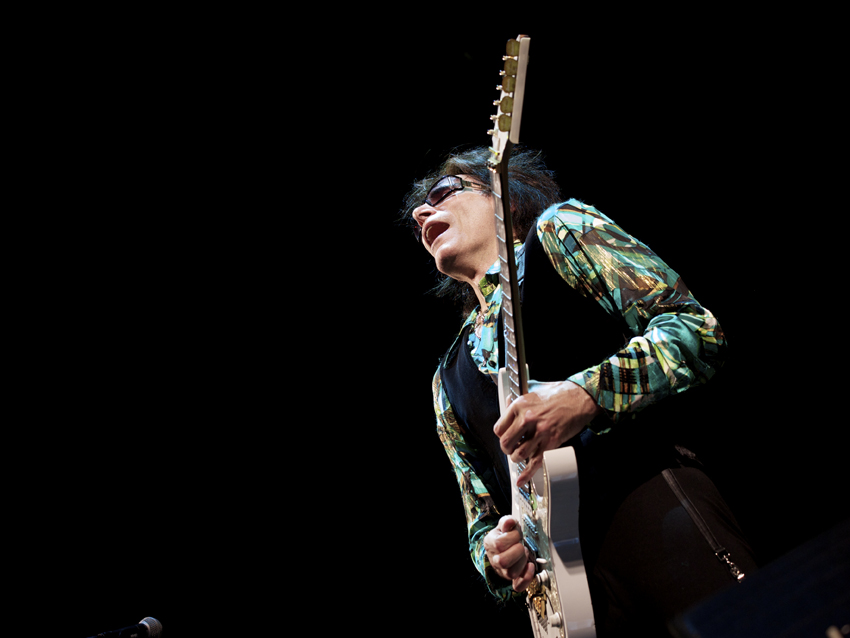

Over the past two years, Steve Vai issued one of his most dazzling albums, The Story of Light, and has toured the world several times. In fact, when MusicRadar spoke with the guitar superstar the other day, he was rounding out an 11-date tour of Russia while eyeing spring and summer treks through Europe and Japan.

Vai filled us in on some of his other summer plans, such as going to camp. No, he's not putting on chaps and heading to a dude ranch, and he's not joining a fantasy baseball league. Better than that: He's launching the Vai Academy Song Evolution Camp, an intimate and comprehensive music experience that runs from June 23rd through the 27th at the Gideon Putnam Resort in Saratoga Springs, New York. Over the course of four days, Vai will take attendees through the entire song process, from inspiration to creation (including mixing and mastering) to distribution. And for guitarists and guitar fans, there will be plenty to savor, with master classes and jams featuring six-string greats Vernon Reid, Jeff "Skunk" Baxter and Guthrie Govan.

For more information on the Vai Academy Song Evolution Camp, including registration, click here. In the following interview, Vai talks at length about the various creative and business elements covered in the camp.

Where did the idea for this kind of camp come from? It’s different from other things you’ve done in the past.

“It is. I’ve been toying with the idea of doing a camp for some time. Some people approached me to do some things, but they wanted me to do a very conventional-style guitar camp, which I think would be wonderful, but I wanted to do something that was different.

“When I thought back to the conversations I’ve had with young musicians and the lectures I’ve given, and when I think back to myself as a young, independent musician, a couple of things came to the surface; there were a few specific things that people were interested in. When you blow all the smoke away, these kids want to know ‘How do you write a song? Where does the inspiration come from? How do you capture it? How do you record it? How do you mix it and master it? And how do you make it available to the rest of the world and tour on it?’ That’s really what’s it’s about.

“So I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to give kids an opportunity to see this process?’ So I created this camp, which as you can imagine is really intensive. There’s various classes through the different days, and I’ll have a band with me. I’ll discuss songwriting and song inspiration, writing music, how it flows and how you communicate musical ideas to a band. They’ll get to see it and participate, to a degree. We de-mystify the songwriting process.

“I also have a professional come in to de-mystify the music publishing thing. Musicians are so intimidated – they don’t understand how publishing works. It is complicated but it’s important. Anybody who writes music or plays a note of music should have their own publishing company. They have to know how to register their music, which is really easy now. We take them through the process of starting a publishing company; in fact, we start a publishing company for the song we write, and we register it. We discuss how to protect your intellectual property, how splits usually go. This is vital information.”

Frank Zappa's advice to a young Vai:

Now, who sat you down and taught you all these things? Was it Frank Zappa? Or did you kind of learn the hard way through trial and error?

“I was a very practical thinker. I’ll never forget this time when I was 19 or 20 years old and I was sitting with Frank, and I asked him for some great wisdom about music. I was waiting for this profound response about being independent and making the music that’s in your heart and all this stuff. And he looked at me and said, ‘Keep your publishing.’ I didn’t know, so I asked him, ‘What’s publishing?’ He wrote down the phone number to an attorney and said, ‘Call this guy and go buy an hour of his time.’

“Jerry Rosenblatt – I went to see him, I spent the money. He explained publishing to me. He started a publishing company for me; he set up sub-publishing for me – to this day many professional musicians don’t know what international sub-publishing is. They throw away a tremendous amount – at least half – of their publishing income because they don’t understand the simplicity of some of these rules. Jerry did all of this for me. To this day, he’s my publishing attorney. I’ve made a lot of money through the years from having this done at 20 years old and protecting my rights.

“Through the years, that’s the one thing people try to take from you – your publishing – because they understand it and what it means. It’s so easy to give it away, but you don’t have to. People have come to me and said, ‘OK, we’re gonna do this, we’re gonna do this, but we want your publishing.’ And I would just tell them no, ‘cause Frank Zappa told me not to give up my publishing. And guess what? The deals would happen anyway – and I kept my publishing. It’s like they turned around, snapped their fingers and said, ‘Drats! We didn’t get him on this one.’”

Aside from teaching certain precepts – intros, verses, choruses, bridges – how can you instruct somebody to write a song? What makes a good song is so subjective.

“You can inspire somebody by showing them the way you do it, and you can talk about the way other people do it. So that’s pointing out various ways that a person can use to find inspiration. But if a person doesn’t have a songwriting mechanism in them, it won’t happen on any kind of real inspired level. And that’s OK – most classical musicians aren’t really songwriters; they don’t write anything. It’s a big mystery and a source of anxiety for kids who want to play an instrument but feel like they need to write a song."

On distributing music on the internet

“On the second day, we record the song, so you see that process, and then you see how overdubbing works, the thought process that someone like me might use to layer a track. And that can inspire some campers and wake them up. It’s happened with me – various aspects woke me up and resonated with me. Engineering was one of them. I’ve always engineered and produced my own songs. Mixing, EQ, mastering – we go through it all.

“And then we take this piece of music and upload it to a digital aggregate that makes it available around the world in virtually every distribution store there is. So now you’re independent and you have this song available. We also have people giving classes on marketing – what it meant yesterday and what it means today.

“You never can tell when the light bulb is going to go off for somebody. For some people, it’s production; for others, it’s publishing. Or maybe some people get the brain muscles going by understanding the role of a manager. You might come to this camp and discover that ‘I just love to play the guitar, and I don’t care about this other stuff, although it’s good to know.’ It’s good to see the process, because you’re not going to see it like this anyplace else.

“And then with people who are songwriters, they see this stuff and it’s like boom – songs just come out and come out and come out. They can’t help it. You can’t really turn somebody into a songwriter if they’re not, but you can at least expose them to things in the music business so that they understand how the infrastructure works. They shouldn’t feel inferior and intimidated or completely ignorant as to how these things work.”

It’s interesting that you’ll be teaching basics of recording, mixing and mastering. When you started out, you needed tons of gear to do it all yourself; nowadays, people can do it –

“They can do it on their laptops. You can make a world-class recording on your computer – easy. The rules have changed quite a bit. Back then, I bought cheap gear; the only good stuff I had was what Frank loaned me [laughs]. The technology and what people can do with it is going to continue to change, but I don’t think the infrastructure is going to change that much. The two things that you’re going to always need in the music business are: one) somebody who brings into the world some kind of musical inspiration; and two) somebody who knows how to get it to everybody else.”

It’s not just recording technology that’s changed since you started out – the internet has changed distribution in so many ways.

“Oh, tremendously. Drastically. Whether it’s good or bad is relative. The opportunities are the same for whoever has the vision to make it real. There are more opportunities, but to be able to embrace them and use them takes a specific kind of vision, enthusiasm and purpose. And what’s interesting is, before all of these opportunities were there, you still needed the same kind of enthusiasm.”

Fear - the great enemy

Getting your music out there is easier now, but monetizing it can still be a big hurdle to clear.

“Sure, that’s always been a problem, even in the old days when records were selling a lot. In the ‘80s, if you were in a band that got a gold or a platinum record, you could still be in debt. The ways that deals were structured then were heavily lopsided against the artist. Most things that were spent on a record came from the artist’s royalties.

“For example, if you released a successful record back in the ‘80s and that record is now available on iTunes, and if you had a conventional record deal, for every download that somebody pays 98 cents for, iTunes pays the same to everybody – 72 cents. That doesn’t matter if you're Sony or Steve Vai. But record companies take the language from the old contracts and they apply it to digital downloads. So you get, say, 13 points on retail, which means that the same song at 72 cents has all these deductions attached to it. Packaging goods – they take away 25 percent for that; free goods are another 15 percent. And they cut your royalty in half if it’s new technology. It goes on and on. If the producer gets three points, that comes out of your 13 – and he gets paid before you. So you can sell a million records and be in debt.

“But you can go to a company like TuneCore and open up an account for $20, and you can upload your record to iTunes. It’ll go to all these iTunes stores around the world, and you’ll get 72 cents a download.”

Have you come across people who are talented musicians, and maybe there’s a good songwriter inside of them struggling to come out, but they can’t seem to get out of their own way? Something is blocking them from realizing the songwriter within?

“Yeah, sure. I’ve seen myself as an example. There’s every type: There’s people who see what’s going on in the world, and they say, ‘I get it. I can write music like that. Here’s my Madonna song. Here’s my Styx song. Here’s my Bob Dylan song’ – or whatever. They have a pantomiming ability, and that’s fine – there’s a place for that.

“A great song is a conceptualization these days. What makes a great song? It’s something that resonates with people. The thing that I think gets in the way with a lot of potential songwriters is the fear of failure. Fear of writing something that isn’t good, fear of being criticized, fear of not fitting in – these things can stop you right in your place."

On Bob Dylan's early songwriting

“We’re conditioned to think that we have to write something either accessible or brilliant. The people who didn’t fall into that trap just wrote music that came naturally to them; they were in touch with their inspiration. And it’s inside of everybody, but it can be covered up by fear. My advice to anybody would be this: Take a moment and think that it doesn’t matter what you write, because it’s going to fail anyway. Write what you want as long as it feels natural to you. Surrender to the fact that you don’t know what’s gonna happen, and that’s OK.

“It’s very freeing, actually. It can take this whole load off. For some people, they might discover that they have no desire to do this if it doesn’t make them famous. And guess what? They’re not songwriters. They’ve been chasing a fantasy that their ego constructed. But if you go to people like Bob Dylan or Tom Waits, people you and I have talked about a great deal, they didn’t have a choice and they didn’t think about it.

“I’ve been listening to Bob and to his inspirations. On his first record he wrote the song about Woody Guthrie [Song To Woody]. He probably didn’t care if it was gonna work or not, but that’s the proof that true inspiration comes from a space of non-expectation. It’s just enthusiasm for the idea.”

And isn’t it interesting how he went from emulating, to a large degree, Woody Guthrie on that first album to Masters Of War a year later – or Blonde On Blonde just a few years later. Talk about discovery!

“Absolutely. And even when he was writing the older stuff, there was this beautiful, youthful angst to it. There was anger about the system, there was heartbreak – all the things that people are attracted to. It’s a cathartic process that people go through if they’re really committed to something. Listen to Tom Waits –The Heart Of Saturday Night to Bone Machine? It’s like, ‘What the fuck, man?’ [Laughs] Or Steve Vai – the guy who wrote Flex-Able and his next record is Passion And Warfare. Where did that come from?”

What happened to that guy?

“Yeah, I don’t know! Poor guy.” [Laughs]

We should, of course, talk about some of the great guitarists who are participating in the camp.

“That part of it’s going to be great. First off, we’ve got Vernon Reid. He’s been a friend of mine for years. I toured with him on the Experience Hendrix tour. He’s such a visceral, very inspired musician, totally fearless. Vernon's amazing.

“And then we have Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter, whom I’ve known for a while. It’s funny: Everybody knows that he’s got various arms in the government and does all these things [laughs], but he’s always had a deep love and passion for the guitar. He’s like a pioneer of guitar goodwill.

“Finally, we have Guthrie Govan, who these days is a sensation as far as technique on the instrument. I watch this guy and I’m fascinated. He’s very intelligent, very sweet, very kind and soft and just naturally inspired. It’s so great that all these guys are doing this. They’ll be teaching during the day, and at night we’ll have a jam. I’ll be playing with whoever is the designated teacher that day – along with campers, and I’ll have my band there. As far as throwing your pick in and having a blast with the guitar, there’ll be a lot of stuff going on.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.