Steve Severin talks 'Banshees, Siouxsie and outlasting punk

"Never pay much attention to what's fashionable"

Introduction

Steve Severin formed Siouxsie And The Banshees with Siouxsie Sioux, the day before they made their live debut at the now infamous 100 Club Punk Festival in September 1976.

Appearing alongside the likes of The Sex Pistols, The Clash and The Buzzcocks, Steve had first picked up a bass less than 24 hours previous. From this audacious, spontaneous beginning, emerged a band whom would go on to (both creatively and chronologically) outlast almost all of their initial contemporaries, continuously evolving and revolving around Steve and Siouxsie’s creative partnership for 20 years.

With reissues of the band’s last four studio albums fresh on the shelves, we asked the immensely articulate Mr Severin about the band’s impulsive beginnings, his and Siouxsie’s “benign dictatorship” and the band’s enduring influence…

The big bang

The stereotype dictates that being musically savvy was frowned upon in the initial punk movement. Is that fair? What were your own thoughts at the time?

"It was just a door opening, which, up until that time, had seemed firmly shut"

“It depends on what you mean by ‘savvy’. Certainly, a lot of the people were just picking up instruments for the first time and didn’t have much experience in playing or writing songs, but I think a lot of us had had a long gestation period of listening to music, which was just as important.

"It was just a door opening, which, up until that time, had seemed firmly shut. I think everybody just took the opportunity.”

Picking it up

Had you played any instruments before the band started?

“No. I’d had this experimental thing at school with tape recorders - just recording sounds and stuff - but it wasn’t particularly serious. It was just 14 year-old kids messing around.

"We had no equipment whatsoever for at least the first six or seven months"

"So, no: the first time I really played anything was the day before the [1976 100 Club punk] festival. We had about a 10 minute rehearsal and Sid [Vicious - our stand-in drummer] said ‘That’s enough!’ and we quit.”

How did you come by a bass guitar?

“I think on the night I used the Subway Sect’s bass guitar, but subsequently [Alternative TV member/Sniffin’ Glue fanzine publisher] Mark Perry gave me a bass guitar. That was my first bass guitar, but I think I took it apart or something!

"But all of the early shows the Banshees were doing, we had no equipment whatsoever. We used to turn up and just use the support band’s equipment. The guitarist always had a guitar, but that was the extent of our equipment for at least the first six or seven months.”

The arrogance of youth

You’re a band that started with such spontaneity, but also had lofty ambitions to push the envelope. How did you reconcile those two seemingly-conflicting ideals?

"In many instances our limitations were our greatest strengths"

“Because we felt the ideas were stronger than anything else. Sheer bloodymindedness was a big part of it: the arrogance of youth. We thought we would just learn as we go along and in many instances our limitations were our greatest strengths.

"That was really our attitude: ‘We’ll use what we’ve got and we’ll keep learning and getting better.’ None of the rest of it mattered to us.”

Was it clear to you when punk was over?

“One of my early quotes was, ’It was over as soon as The Damned played’! It was different for us because we didn’t give it a name, we didn’t think of it as a movement. This was all put upon us by the press and, subsequently, as bands started springing up in every little town, it became sort of secondhand received information about ‘what they were supposed to do’. It was all kind of weird.

“We felt kindred spirits with some bands of the time, like The Buzzcocks and Wire, for instance, but I think if you ask anybody from the sort of so-called ‘first wave’, they wouldn’t really call it a movement. Everybody was quite competitive.

"I think it was quite clearly defined when the second wave of bands like Sham 69 and Cockney Rejects came along that were taking more of a Ramones-type template, but without the humour. Then it had moved on, so we didn’t really take much notice of all of that.”

Guardians or dictators?

You’re one of the few bands to emerge then that not only survived but successfully developed. What was the key to that longevity?

“Lots and lots of factors. I always tend to think that the key moment was when the first guitarist and drummer just upped and left in Aberdeen in 1979 [Kenny Morris and John McKay quit the band on the spot after an argument at a record signing].

"If you’re going to do something that has a very strong identity, you have to have guardians of that identity"

"That solidified Siouxsie and I’s determination to keep things going and that was a fairly enormous trauma for the band. I don’t think anybody has ever done that to anybody else in the history of rock! [After that], we tended to jettison personnel as and when we saw fit to keep everything fresh and moving onwards.

“The other thing was never to pay much attention to what’s fashionable. Anything that’s trendy at the time, you just completely ignore it.”

Do you feel the fall-out of Aberdeen was beneficial because it gave you and Siouxsie an authority, as the core of the band?

“Well, we always were [the core]. That’s part of the reason why they [Morris and McKay] absconded when they did. They’ve never told me and I don’t really… care… but I imagine they felt like they weren’t getting their opinions across, or whatever. But it was always a benign dictatorship, under two people.

"If you’re going to do something that has a very strong identity, you have to have guardians of that identity, you know? When it’s two people, you’re kind of keeping each other in check.”

An analogue band in a digital world

What was your most significant development as a musician, during the band’s lifetime?

"If you look at our career, we span the analogue era and the digital era, which I think is really important"

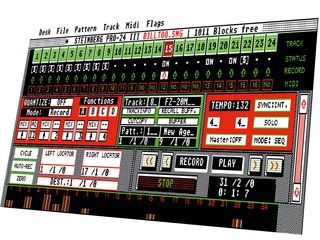

”Probably the most significant change for me was computer sequencing. I think it was ’87, when I got [Steinberg’s early Atari program] Pro-24, the precursor to Cubase. Instead of just working with a recording studio and doing home demos on a drum machine and keyboards, I could just sit there with a computer screen and invent whole parts of everything very quickly.

“As a band, if you look at our career, we span the analogue era and the digital era, which I think is really important. We learnt our craft in the analogue world, with tape loops going round and round the room and spending ages recording broken glass and all of these studio effects that were kind of ‘Blue Peter’ by comparison. We took that experience and used it going forward.”

How did your gear choices change over the years?

“I think the biggest change was moving from standalone pedals to a TC Electronic rack-mounted thing in about ’86 where I could program in various effects throughout a song. You could change it up as you were going along. That’s one thing we were already trying to do.

“John McGeoch [noted Banshees guitarist, 1979-82] invented this fantastic thing where he got the roadies to cut down a mic stand in half and then put an MXR flanger on top of it.

"With one hand he could be playing and then with the other he could be changing all the parameters and produce a sound that you just couldn’t get without that kind of control. We were always trying to push it to see how much control we could have over effects.”

Getting along

There was, understandably, some friction between yourself and Siouxsie over the band’s 20 years. How did you ensure you had a working musical relationship in spite of personal feelings?

"We created an entity to project all our hopes and dreams on"

“I think that the band was always an entity bigger than our separate egos. I don’t think either of us are particularly great at self promotion. Siouxsie more so, obviously, but she had to come to terms with that because she’s the front person.

"But for me, I’m quite naturally shy and don’t particularly like the spotlight, so if I can project it all into the idea of a band, then it makes sense to me. Then I will walk around saying, ‘The band is the best thing EVER.’ Whereas I wouldn’t walk around saying, ‘I’M the best thing ever.’

"We created an entity to project all our hopes and dreams on and I think that’s it, really.”

Ploughing new pastures

What do you think the band’s legacy is?

"I hope we're an example to people that you don’t necessarily have to plough the same field"

“[Long pause]… I think the strongest thing that comes through is the range of material that we did and the fact that no one album really sounds like the next one.

"There are echoes in each one, but they move on and I hope that would be an example to people that you don’t necessarily have to plough the same field each time. Maybe you won’t be as successful if you do that, but it is possible to sustain a long career as long as you keep moving and don’t fall victim to fashion.

“Where we stand in the scheme of things, I’ve no idea, really. We’re so outside of stuff and I’m not really interested in where we are in ‘the pantheon’. I just think that’s all a load of baloney!”

Re-mastered reissues of Siouxsie And The Banshees final four studio albums Through the Looking Glass, Peepshow, Superstition and The Rapture are available now.

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

Most Popular