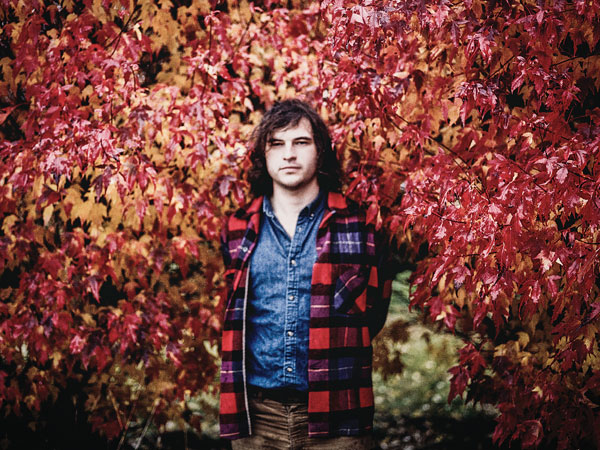

Ryley Walker: the last living drifter talks new album Primrose Green

The gifted fingerstyle folkie on his journey thus far

Introduction

He’s the 25-year-old fingerstyler who’s a freewheeling inheritor of the spirit of Jansch and Graham. Oh yeah, and he made up his excellent second album, Primrose Green on the spot. Let’s take a stroll with Ryley Walker...

"Ryley’s playing calls to mind the likes of hallowed UK folk heroes like Bert Jansch and Davey Graham"

Chicago’s Ryley Walker is the kind of figure whom it’s tempting to describe as ’not of his time’, but perhaps in this age of genre blur the very opposite is true. The sprawling pastoral folk evidenced on second album Primrose Green has undeniable roots in 60s and 70s songwriters, but it ranges far wide of nostalgic reverence.

Ryley’s playing calls to mind the likes of hallowed UK folk heroes like Bert Jansch and Davey Graham, while his writing has much in common with the heady jazz/ blues-based jams of Van Morrison and Tim Buckley - all names we do not drop lightly.

His mercurial fretboard wizardry is complemented in no small part by the incredible ensemble of Chicagoan jazz improvisers in his band - and the majority of the album was made up on the spot and recorded in first takes. Prodigious talent positively wafts from it.

Still just 25, he’s utterly focused on music and little else. A man who lost half his hearing in an accident but found joy in acoustic music afterwards, Ryley Walker joins a long lineage of folk vagabonds.

His kind is all too rare, so we took the chance to separate the man from the fast-forming myth...

Raised in Rockford

You were born and raised in Rockford, Illinois. What’s it like growing up there?

"That’s my motherland. It’s your classic Midwest town with lots of busted-up old factories and ‘Reaganomics’ in full effect. There were a lot of weird old factories downtown and a lot of angry people. There’s not too much going on there really.

"I had a big habit of going to rummage shops and seeking out Led Zeppelin records, which was a big thing for me. At a pretty young age it kind of became all I cared about. Mostly, I just hung out with my friends and busted-out windows in old factories and skateboarded and attempted to have a band that was good - but we were always terrible."

"I’m deaf in my left ear from the accident and that kind of made me just want to get out there and play the music more"

Then you moved to Chicago. Was that explicitly to follow a career in music?

"No. Rockford is only about 60 miles or so from Chicago, so everyone ends up going. You either stay in Rockford, have a kid and join the army, or you move to Chicago and hope to do something different.

"The first night I got my own place [in Chicago], it was like creepy tornado season during the late summer. I lived by Wrigley Field, where the [Major League Baseball franchise] Cubs play, and they had to close-out the game. We just stayed up all night getting drunk and listening to Waylon Jennings records and feeling like our house was about to fall down. It was kind of a cool first night."

We read that you had a bike accident in Chicago that left you deaf in one ear. What happened?

"I was just riding my bike back home from a friend’s house and I got hit by a drunk driver and he got away. My girlfriend was behind me and she was the one who saw it.

"It was years ago, so it’s all good now, but I’m deaf in my left ear from the accident and that kind of made me just want to get out there and play the music more. I didn’t want some drunk asshole to shut my life down, so I started playing guitar as much as I possibly could at that point."

Wayfaring stranger

Do you think, having lost 50 per cent of your hearing, it made you appreciate music at its most basic level?

"Absolutely. I was just thanking my lucky stars the whole time that I was alive and I could still hear and I was able to play the guitar. It made me appreciate it tenfold. That was the time I was practising all day because I didn’t really have anything else to do.

"Having a lot of things that keep me from touring a lot bothers me and what makes me want to tour is that I’m curious"

"It was 10 hours a day at that point. It was just: wake up, drink a black coffee, smoke a big doobie and then just jam all day. I was just honing in on what my voice was and what I liked to play."

Do you still practice frequently?

"I still practice every day, or I try to - I’m busier nowadays - but I practice all the time. I usually mess around with tunings. I’ll try to find new tunings and new positions with the capo. That’s usually where I’ll find my songs - making up tunings on the fly and just jamming with them and just improvising all day. The mood sets where I’m at, so it’s a very exploratory process."

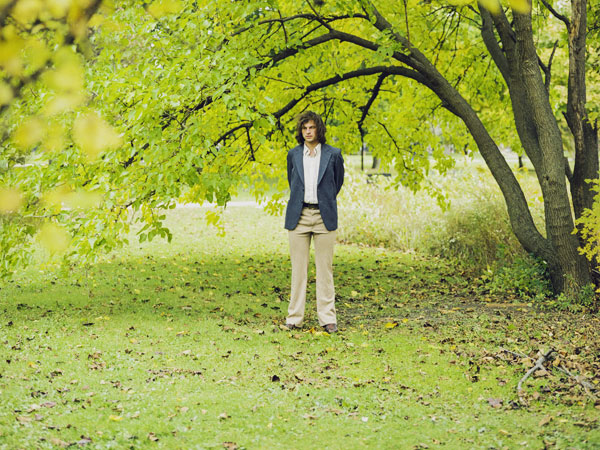

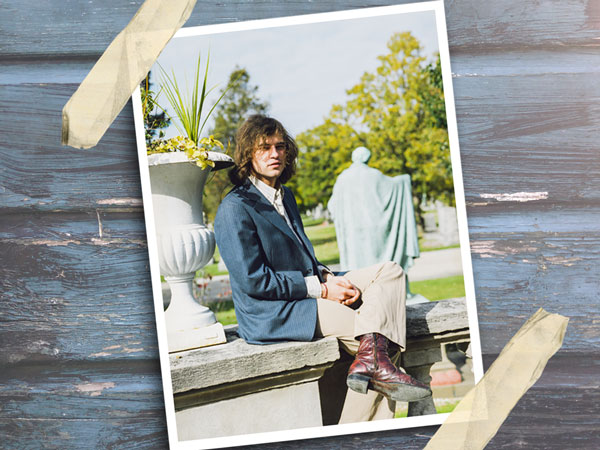

You’ve got a reputation as something of an adventurer and drifter. Is that fair?

"Yeah, I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody, but that’s the way I live my life. I’ve got a stack of records and a guitar. I’ve got a couch at my friend’s place that I stay on, and I’ve got a new pair of boots, and that’s about all I have these days.

"Having a lot of things that keep me from touring a lot bothers me and what makes me want to tour is that I’m curious. I always have been. I grew up in the Midwest, if you drive 500 miles in either direction it’s just corn fields - so that’s always stuck with me. I’ve always wanted to keep going. And keep getting better at guitar."

Jazz hands

Do you think that’s why you identified with the comparatively more exotic British folk players?

"I’m a big fan of 60s and 70s folk music on either side of the ocean, but I really like how far-out those British guys were. Over here, it’s not bad music, but it’s just white people playing post-war blues, whereas over there the UK players definitely took influence from American blues but they took a lot of weird influences, like Indian music, or classical music, or traditional Irish and Scottish songs.

"There’s a really huge scene in Chicago of improvised music and always has been. It’s a really collaborative town"

"It was rooted in the past, but it was this forward-thinking avant-garde sort of music. That’s what makes them these kind of shadowy figures that I admire, on the fringes of music and the fringes of popularity. They were great artists first and musicians second and who changed a lot more than they knew, I feel."

How did you find and recruit the remarkable jazz musicians who play in your band?

"Fortunately Chicago is really rich with, I think, the best jazz music in the States. There’s a really huge scene here of improvised music and always has been. It’s a really collaborative town. Every musician in Chicago just wants to work every single day. It’s so cheap to live here that it’s pretty easy to get by as a musician - well, perhaps not easy, it’s doable. It’s not New York or LA where the rent is nine times the rate."

Why do you think jazz players were interested in teaming up with a folk-influenced player?

"I think, because there’s not as much competition here. We know that no one’s going to come here seeking us out, so we seek each other out first. In New York, if certain people see you, you can make a lot of money, but in Chicago you’re not going to make much - you’re going to bite the dust and you’re going to do it because you fucking love it.

"So you’re seeking out musicians to play with all the time and it’s important to stick together because we don’t have a big industry for music: we only have the s**tty winters and each other, so I’ll roll with my friends who are really great jazz musicians."

Guild-ed gear

Who produced Primrose Green and where did you record it?

"This record was made here in Chicago at Minbal Studio and my friend Cooper Crain did it. He’s a really talented guy - he’s in that band Cave who are on Drag City. They’re kind of like a groovy krautrock band - and he had a big hand in recording and a big influence on it, definitely, with all the weird instrumentation and the fuzzy sounds.

"I’ve got this Guild D-35 that I love and swear by. That’s the one I’ve used exclusively for the last few years. She’s a warhorse"

"The studio is on the west side of Chicago in this industrial wasteland part of town. You can walk a mile and maybe you’d find a liqueur store and a cheque-cashing place, there’s just nothing going on over there.

"It was recorded in May of last year and I remember it was the first day I could wear shorts. In Chicago, you really can’t wear shorts until May. So the day we started it was the first day I could wear shorts and I felt incredibly happy."

What kind of guitar equipment were you using on the recordings?

"I’ve got this Guild D-35 that I love and swear by. That’s the one I’ve used exclusively for the last few years. She’s a warhorse, she’s been all over the world with me. I got it at this second-hand shop, way up in Chicago that’s a vintage rock ’n’ roll, kind of low-key place. I gave the guy like $800 cash - they let me have a real good deal - and I walked out with it and I’ve played it every day since."

Why did you opt for that guitar?

"I just picked it up and had to have it. It’s really old, too - a ’73 or ’74. Those are really easy to come by in the States. They’re still not that popular. Not like an old Martin or something. Guilds are like a cult guitar. It’s like smoking American Spirits or drinking Red Stripe. It’s like a cult beer. It’s like, ‘Woah! You’re drinking Red Stripe! I’m drinking Red Stripe!’ or ‘Woah! You’ve got a Guild!’

"I like that community among the people who have Guilds. Once you have a Guild you’re like, ‘I’ve got to get another Guild.’ Nothing else matches it."

Is that all you were playing on the record?

"Yeah, that, and on the last track [Hide The Roses] there’s a Gibson Hummingbird that I played, which was really not in good condition. The strings had to have been like five years old, but at that exact moment in time I liked it. But, yeah, for the most part I’m playing that Guild D-35. I’m playing the hell out of it."

In the moment

The album sounds very free-flowing. How much of the sessions were improvised?

"Most of the record was improvised, I’d say. Going into the studio I had mostly bits of lyrics and riffs and then I just kind of worked them out as it came. That comes from playing with those jazz guys who are just brilliant improvisers.

"If you want to be a good guitar player, hang out with good guitar players. Don’t hang out with bad guitar players."

"The first track we did was Summer Dress. We did that one first take and it kind of has this groovy jazz intro and it was classic bassist and drummer thing, they were like: ‘Can we just start this off?’ I just was like, ‘Alright, go ahead!’ and it turned out great. One of those ‘in the moment’ ideas."

Which track on the album do you think is the best example of what you’re trying to achieve, musically?

"There’s a song called Love Can Be Cruel, which I think is really interesting. It kind of has this Pentangle-y jazz riff and at the end there’s this extreme like Terry Riley section where it’s these groovy synthesised parts and fuzzy guitars and really no vocals. It goes with the whole experimental idea of the record."

What, to you, is the secret to fine acoustic guitar playing?

"Hanging out with acoustic guitar players and buying records all the time. If you want to be a good guitar player, hang out with good guitar players. Don’t hang out with bad guitar players."

You’re receiving a lot of praise for this album. Are you worried that success will ruin your drifting lifestyle?

"No, because I’m pretty sure that nobody in this world is going to make a jazz folk player successful, ever in its history. But I’m perfectly comfortable on the couch - don’t worry about me!"

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.