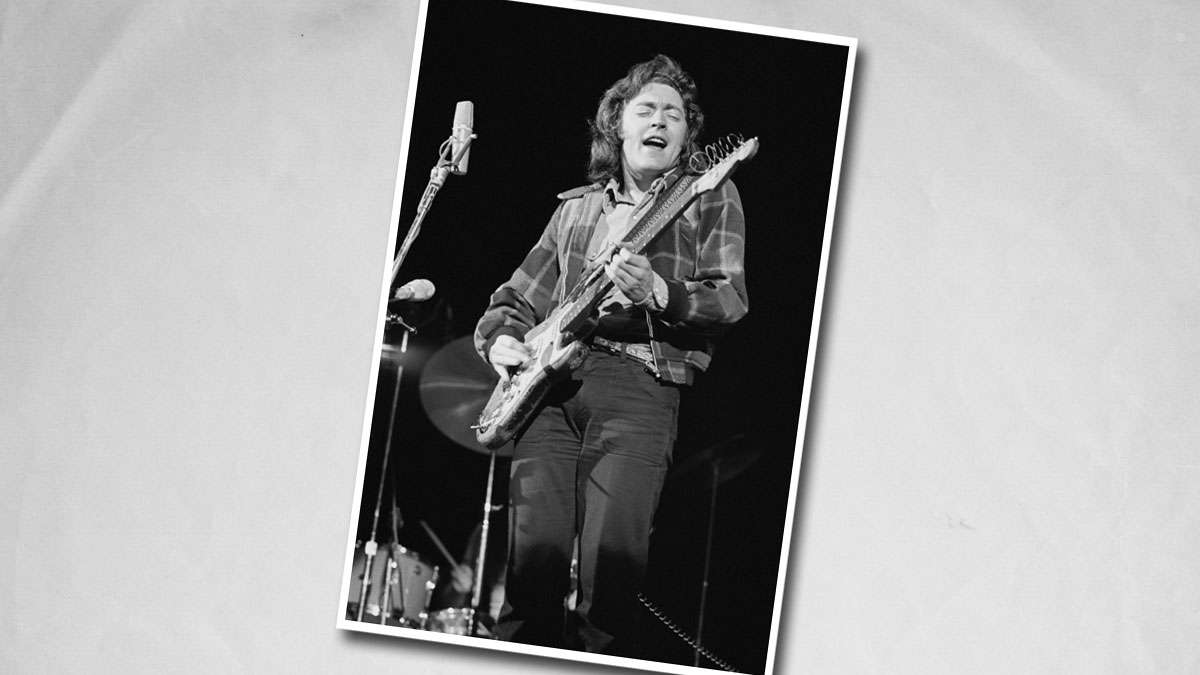

Rory Gallagher: the magic, the modesty and Muddy Waters

Donal Gallagher on his brother's rare talent

Introduction

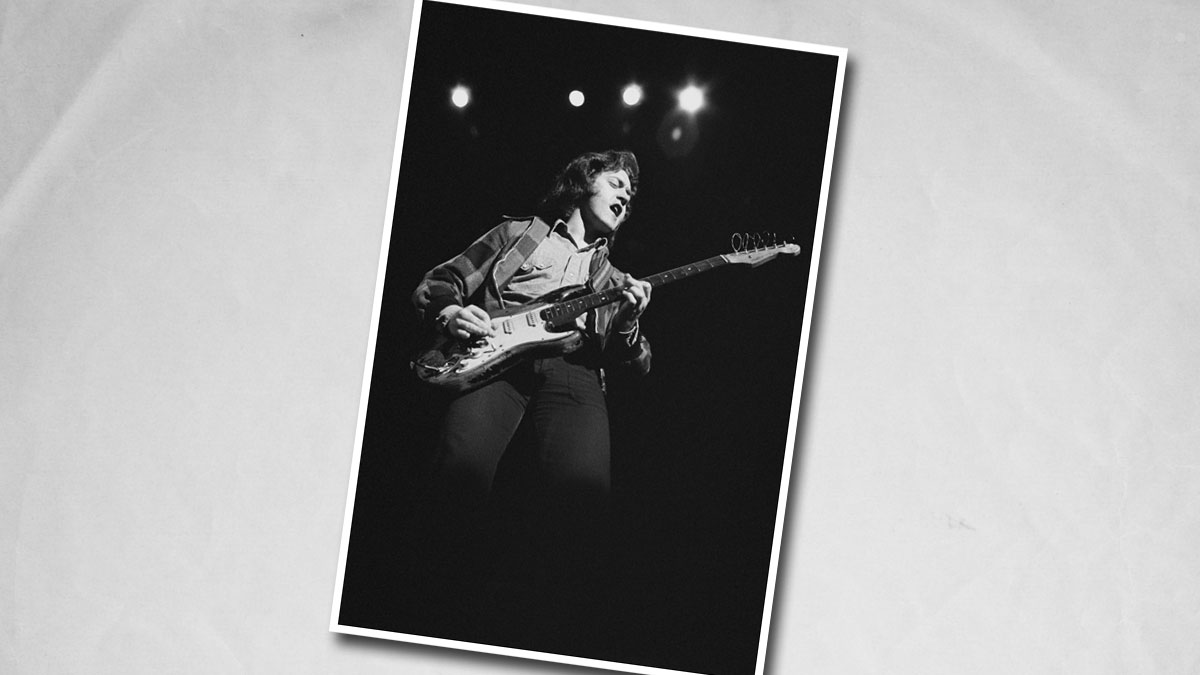

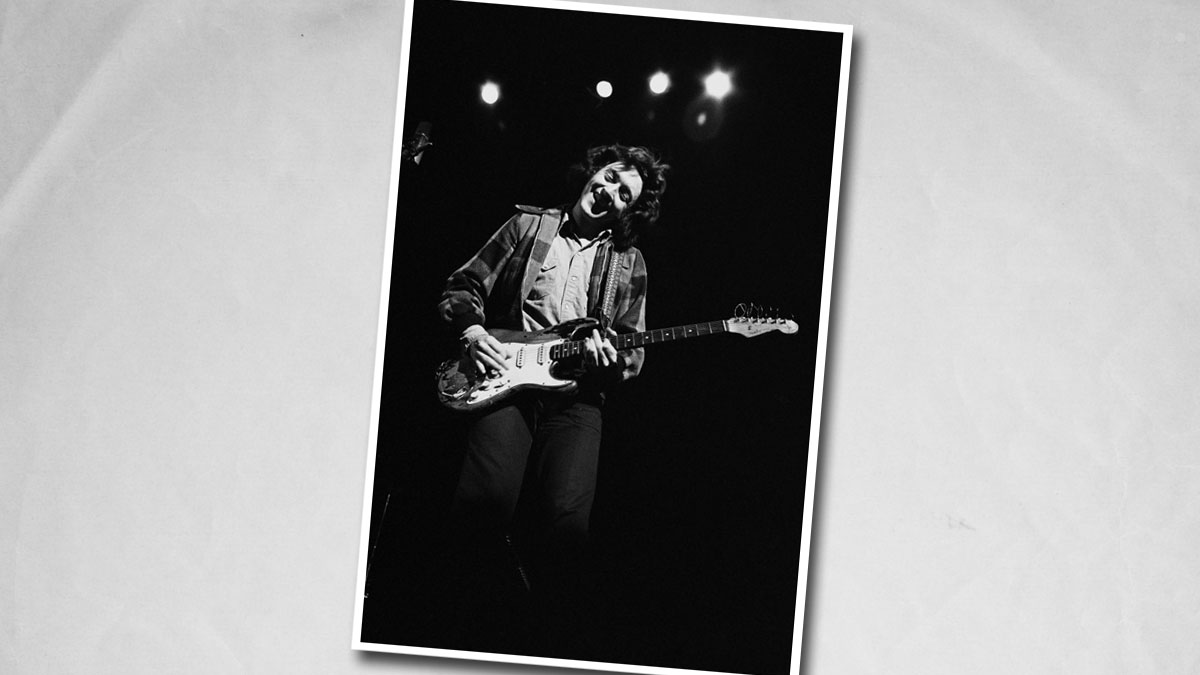

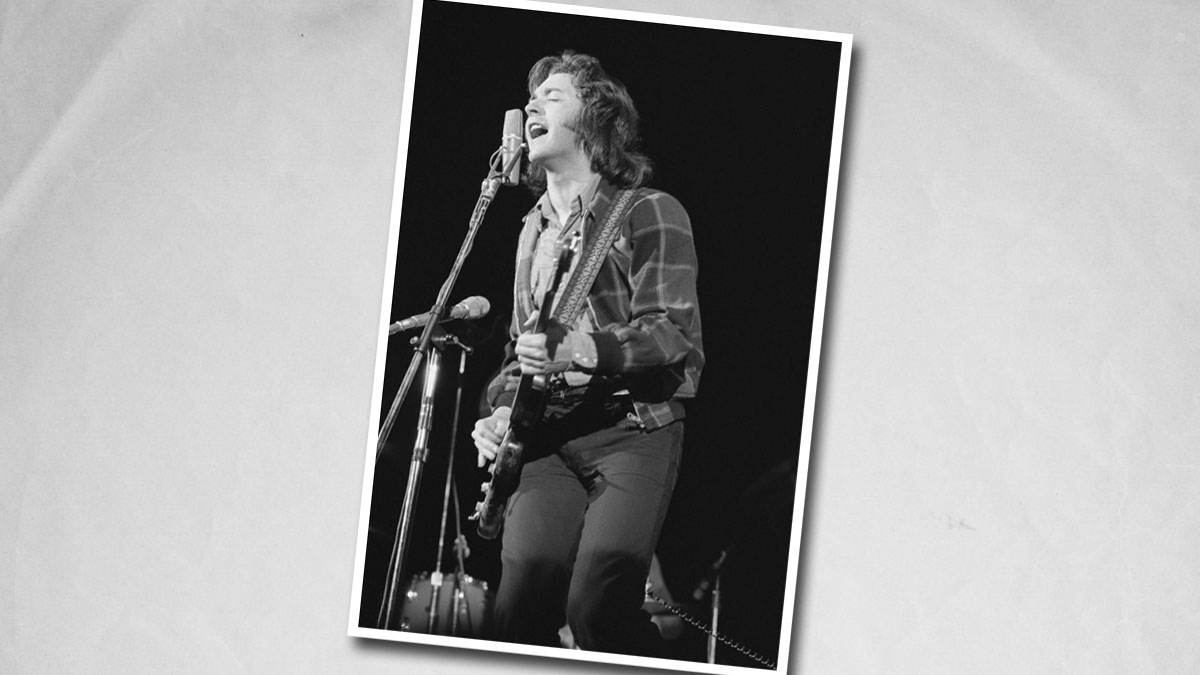

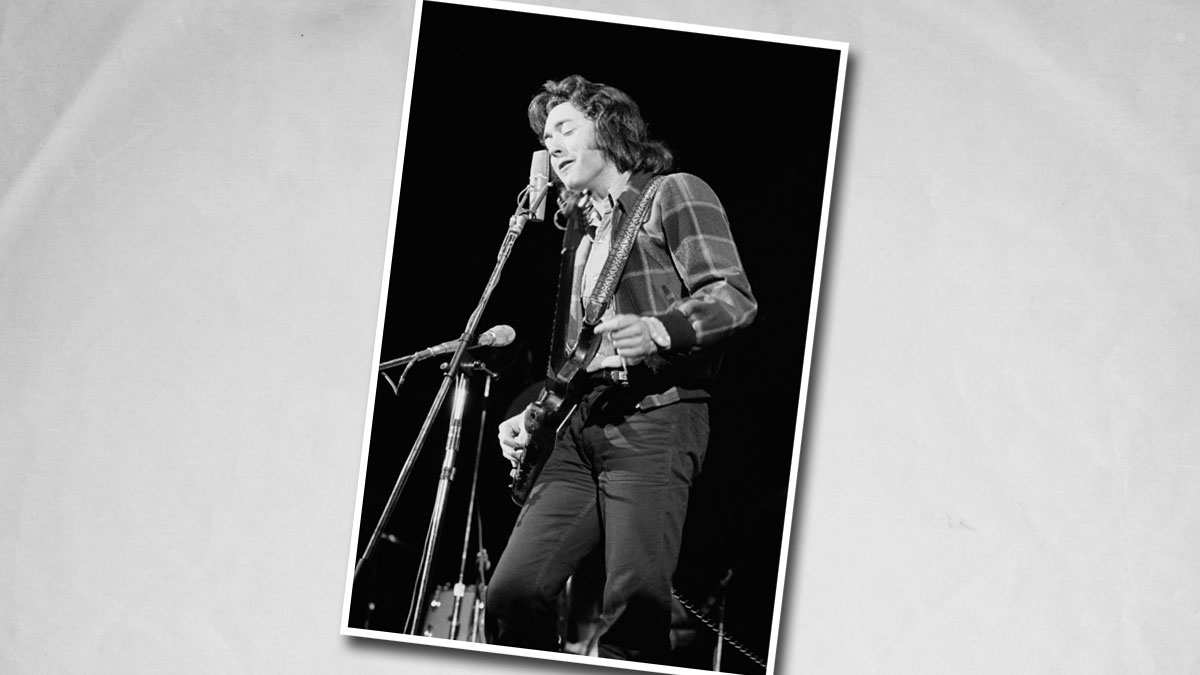

Rory Gallagher was one of the most important and incendiary blues guitarists of his generation. Though he sadly passed away at the young age of 47 in 1995, the Irishman’s amazing blues legacy still resonates 20 years later. To mark two decades since his tragic death, we sat down with his brother, Donal, to discuss the magic of his music and the unique instruments he used to make it.

Montreux Jazz Festival, 1977: “I’m gonna hang these young boys by their toes up here tonight,” Albert King said when he walked out on stage.

The great bluesman was directing his comment at Rory Gallagher and Louisiana Red, who were to join him at times during his set on that occasion. As introductions go, it was hardly welcoming, and must have been particularly intimidating for Rory.

But as the recording of that night shows - notably on King’s nine-minute-long reading of As The Years Go Passing By - Rory more than justified his presence, reeling off an extended fiery solo that perfectly complemented King’s own playing.

Unwanted

Almost four decades later, the details are still perfectly etched in Donal Gallagher’s memory.

“That wasn’t a very cordial affair,” he recalls. “Rory was under a lot of pressure at the time. It was the one break he had for holiday, and because Warners wanted to sign him, I’d gone to California. Then, Claude Nobbs, who was the director of the Montreux Festival, said that he had Ronnie Hawkins and The Band due to appear for a reunion gig, but Robbie Robertson had refused to play. Would he stand in?

Rory was really up against the wall, but when you listen to the album, he does a smashing couple of solos

“The next night, Albert King was due to play and was being recorded for the album that became On The Road. I think the record company wanted to get Rory on the album, too, and needless to say, Rory was chuffed to bits. He went down to find that there wasn’t going to be any rehearsal and King wasn’t being at all communicative. Rory felt very awkward and that he wasn’t really wanted.

“When eventually he was called on stage, the band didn’t make it very pleasant for him; there were no keys written down and it was a case of being thrown in the deep end. If you could swim, fine - if you couldn’t, tough!

“Rory tried looking at Albert’s fretboard to see what key he was in, but that didn’t help. Albert King had such a unique system of playing - the guitar was upside down and he was left-handed. Rory asked one of the brass players, who just said, ‘B natural, boy - B natural.’ And that was it!

“Rory was really up against the wall, but when you listen to the album, he does a smashing couple of solos and really acquitted himself well.”

One of a kind

As Donal talks about his brother 20 years after his untimely passing, it’s a poignant reminder that there’s never been another guitar hero quite like Rory Gallagher.

If you spoke to Rory, he’d always talk about some obscure blues guy, never about himself

From the earliest days, when he blew out of Cork with Taste, his brass-knuckle-in-your-face approach to playing was always capable of outgunning anyone else on the block. Only the formative blues players he adored, such as Muddy Waters and Albert King, were in the same league.

Rory was always a triple threat; it’s difficult to think of any white blues player who has ever matched the intensity of his performance, the brilliance of his guitar playing or had the strength of his songwriting. And the blues in all its forms was the cornerstone, the essence of everything he did.

“If you spoke to Rory, he’d always talk about some obscure blues guy, never about himself, and there never seemed to be any musical barriers to his playing,” Donal continues.

“His blues appreciation stretched from the hard-line electric Chicago style of Muddy Waters, through to the subtle country blues of people like Big Bill Broonzy and Blind Boy Fuller.”

A Taste of success

Nowhere is this more evident than in Rory’s early Taste recordings, now reissued as part of a four-CD box set.

A jazz-inflected version of Leadbelly’s Leaving Blues, heavily borrowing from folk icon Davey Graham’s version on Folk, Blues And Beyond, sits comfortably alongside Gallagher originals, plus Howling Wolf’s Sugar Mama and Muddy Waters’ Catfish.

Taste took a lot of flack from the so called ‘bluesers’, and they were intimidated by the Mayalls of the world

“Rory was also a huge fan of Bo Carter and the Mississippi Sheiks. He wrote a song about them, and it was one of the reasons that he bought his National Steel guitar. He loved the idea of these guys standing on Mississippi street corners wearing turbans so that they would be noticed, banging away on loud guitars,” Donal adds.

After Taste first moved to London, Rory struck up a firm friendship with Alexis Korner, at the time very much the spiritual godfather of the British blues movement.

“Rory got to play on a radio show that Alexis was running at the time, played some beautiful acoustic guitar and they hit it off really well. Subsequently, they often ended up on the same gigs together and became very close friends, which is why Rory wrote the tribute track to him, Alexis, which is included on Fresh Evidence.”

Despite this, Donal still ruefully recalls the antipathy Rory received in some circles.

“Taste took a lot of flack from the so called ‘bluesers’, and they were intimidated by the Mayalls of the world - people who, ironically, had once been very happy to share bills in the North of Ireland where Rory was very popular.

“Bands like Cream and Fleetwood Mac knew Rory and rated his playing, but there was a slight resentment because it wasn’t a London thing: ‘You can’t play the blues if you don’t come from London.’ This even spilled over into the press, with Saint Someone of the Blues saying that because Rory was Irish, this really shouldn’t be happening.”

The Taste test

In 1969, Taste embarked on the ill-fated Blind Faith tour of America. Intended to expose the band to large American audiences for the first time, the tour ended up being a total disaster, but it did provide Rory with the opportunity of experiencing the blues first-hand in its home environment.

Muddy called Rory to the stage, but before he got there, Steve Marriott went up and took the guitar!

He hung out with slide master Hound Dog Taylor in a Southside Chicago juke joint, and Donal laughs as he remembers how Rory missed the opportunity to play with his main man, Muddy ‘Mississippi’ Waters.

“We went down to see Muddy and his band playing in a New York club called Ungano’s. The gig was very badly attended by the public, but it was the million dollar audience with Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Steve Marriott, Buddy Miles and Hendrix all sitting there.

“At the end of Muddy’s set, it inevitably turned into a jam session and Muddy called Rory to the stage, but before he got there, Steve Marriott went up and took the guitar! In typical fashion, Rory just shied away and backed off.”

Muddy feat

In 1971, Rory finally got his opportunity to play with Muddy Waters when he was invited to appear on the London Muddy Waters Sessions album.

Rory was always far more into the Chicago guys’ cut-to-the- chase, straight-in-your-face kind of guitar

“Rory was always far more into the Chicago guys’ cut-to-the- chase, straight-in-your-face kind of guitar, and particularly the sharpness of the bottleneck style, than the BB Kings,” says Donal.

Certainly, the two men appeared to get along well, and Rory’s interaction with the Chicago master on tracks like Walking Blues provides an authentic edge to the recording, sadly missing with some of the other players.

Like his blues idols, undoubtedly Rory would have liked to keep playing guitar until he dropped, but in a 1990 interview, there was a worryingly ominous foreboding in his comments.

“Over the last four or five years, I’ve wondered if I can keep it going. I think if I can get over the next couple of months, when the album comes out and I can get back touring, I’ll go for about 60. That would be my dream, and a fair time to retire.

“It’s not so easy as when you’re 19, or 25, or 30 - but it’s still better than retiring to Buckinghamshire, getting a mansion and six corgi dogs and writing the next rock opera!’’

When Rory Gallagher tragically died on 14 June 1995 at the age of just 47, we lost not only one our greatest guitar heroes ever, but a guitarist who was undoubtedly one of the finest blues players ever to emerge from this side of the Atlantic.

The brand new four‑CD Taste anthology, I’ll Remember, is available now on Polydor Records.