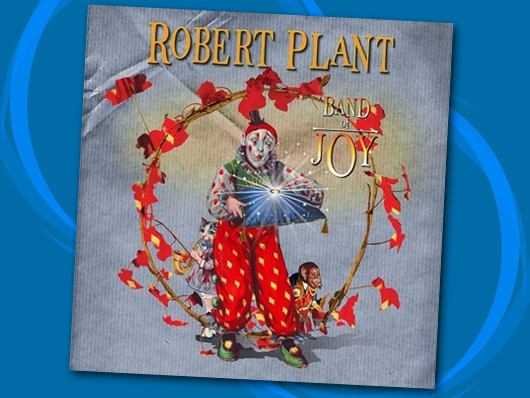

Robert Plant: Band Of Joy review track-by-track

Is Plant's new album for 2010 Raising Sand II?

Robert Plant: Band Of Joy album review track-by-track

As word filtered through that Robert Plant’s sessions with Alison Krauss for the follow-up to 2007’s multi-million seller Raising Sand ended abruptly, a question mark hung over what the erstwhile Led Zeppelin frontman would do next. As it transpires, his new album Band Of Joy is still rich with the atmospheric Americana of its predecessor, but with a few notable tweaks.

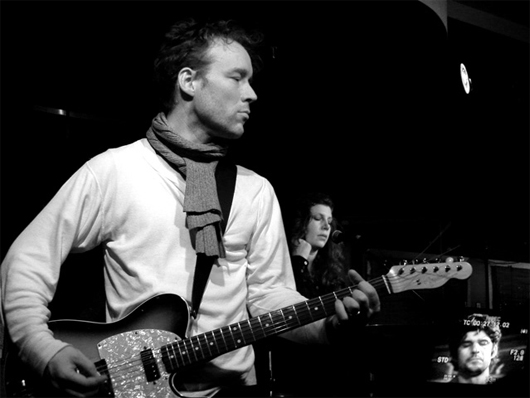

The chemistry might not have been right for a seconding outing with Krauss, but Patty Griffin steps into the female vocal foil shoes with style, although her contributions are restricted largely to back-up harmonies, as opposed to being a full-on duet partner. However, the key collaborator here is Buddy Miller, who takes over from T Bone Burnett as producer, and is the lynchpin of the studio sessioneers (also named Band Of Joy, after one of Plant’s earliest groups).

Recorded at Woodland, the Nashville studio now owned by Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings, and with a heritage that made it a favourite among veteran country stars such as Chet Atkins and Glen Campbell, the location would appear to have been integral to Plant soaking up over a century of American music. Plant seems to have set out to deliver an evocative history lesson in the form of some mesmerising tunes whose impact is heightened with each play.

First up: track one, Angel Dance

Angel Dance

Plant’s take on the Los Lobos song reinvents it as an almost eastern mystical dirge, the singer imparting the near nursery rhyme optimism of the lyric over a swirling backdrop created by Miller’s echo-laden guitar riff (shades of Bo Diddley) and some fine mandolin from Darrell Scott and Marco Giovino’s military tattoo-style pounding percussion.

House Of Cards

In pre-release interviews, Plant has continually referred to English folk figureheads Fairport Convention’s own musical excursions into the American heartland.

Here, he overhauls a track written by Fairport’s Richard Thompson in the late '70s - a stuttering metaphor-filled story underpinned by Byron House’s fluid bass. The vocals (Griffin making her first appearance) play a call-and-response game with Miller’s guitar twang and more intricate mandolin from Scott.

Central Two-O-Nine

The album’s only original track, co-written by Plant and Miller, is nonetheless seeped in bygone hues, combining a hoedown banjo with a gritty blues rhythm that recalls the acoustic blues of Robert Johnson.

Realistically, it could have been lifted from Led Zeppelin III, but its simplistic lyric of a man waiting for his lover’s train express a sentiment as old as the railway itself.

Silver Rider

Slowcore indie band Low have long been among Plant’s favourite younger bands, and he’s opted to cover two tracks from their 2005 album The Great Destroyer.

The first finds a reverbed Miller delicately picking out lines while Plant limits his voice to a near whisper. Griffin’s contribution is arguably the most telling, a ghostly hush that drifts across the speakers to give the song an ethereal atmosphere.

You Can't Buy Me Love

A sprightly upbeat soul dancefloor filler in its original '60s incarnation by Barbara Lynne, here it’s delivered as a garage-like fuzzbox classic that could feasibly have been produced by The Yardbirds or, given its title, mid-period Beatles.

Indeed, Miller’s choppy guitar could have been lifted straight off the Fab Four’s She’s A Woman.

Falling In Love Again

Another little-known '60s soul tune, Plant doesn’t veer too far from the Kelly Brothers’ original.

The entire band weigh in on the gospel doo-wop harmonies, while Plant offers a delicately quivering lead that will be familiar to fans of his brief diversion with The Honeydrippers in the early '80s. Instrumentation is kept to a minimum, but Miller’s discreet guitar perfectly complements the voices.

The Only Sound That Matters

Perhaps the most straight 'country' selection on the album, and originally performed by obscure Nashville treasures Milton Mapes.

It could almost be a shuffling Springsteen ballad, all late-night yearning and valentine similes, Plant’s double-tracked vocal twisting its way through the spaces between Scott’s lap steel and Miller’s subdued acoustic plucking.

Monkey

The second cover courtesy of Minnesota’s Low, this is the album’s most spooky track, with Plant and Griffin harmonising on a disturbing story of possession and control.

Miller adds a modicum of wailing feedback to set the tone, but it’s the devil dance created by House’s thrumming bass and Giovino’s understated drums that stays with the listener.

Cindy, I'll Marry You Someday

What started life as a 19th century negro folk song has, down the years, been reinterpreted by such diverse performers as Elvis Presley, Warren Zevon and Nick Cave.

Plant all but returns it to its origins, accompanied in the main part by Scott’s banjo Giovino’s brush drums, with Miller adding an intermittent 21st century sheen on a single string of his electric.

Harm's Swift Way

Townes Van Zandt is perhaps most revered for the dense and sombre poetry of his country output, but this is among one of his most accessible tunes.

A no-nonsense strummer, albeit with a heartbreak lyric, Miller’s guitar work places it in the radio-friendly canon of, say, The Jayhawks or Ryan Adams, while Griffin relishes playing Emmylou Harris to Plant’s Gram Parsons.

Satan Your Kingdom Must Come Down

A Carolina gospel song that historians believe dates from the 1930s, it has also been attempted in recent times by Uncle Tupelo. Plant’s arrangement is somewhat sparser, his voice full of foreboding while Scott’s banjo plucks a menacing accompaniment.

Again, Miller floats by almost unnoticed in the background with muted echo of a guitar part.

Even This Shall Pass Away

Wire-brush drums, freeform Hendrix-like guitar and a vocal that’s probably the closest Plant has ever come to rapping.

It’s an intriguing mix, especially on a song that began as a 19th century poem by journalist and anti-slavery campaigner Theodore Tilton. It’s as tribal as it is testimonial, providing a fitting closer to a mercurial collection of songs that surprise at very turn.

Verdict

Lazy shorthand would have you believe that, despite the absence of Alison Krauss, Band Of Joy is to all intents and purposes Raising Sand, part two. However, while both albums clearly share a template, Plant’s latest is further-reaching in both its investigations of America’s rich musical heritage and its sonic ambition.

It’s the sound of Plant returning to a well-thumbed encyclopaedia but paying more attention to the smallprint footnotes. As tempting as a big bucks Zeppelin reunion might have been (not that he needs the cash), Plant has instead chosen to stretch his creative muscles and look further back in time than the halcyon days of the rock legends who made his name.

Few artists in their early 60s have ever sounded so hungry, so engaged, so enthused by music, and while the jury may still be out on whether Band Of Joy is a better album than Raising Sand, it is certainly no less of a triumph.

Liked this? Now read: Eric Clapton new album review: track-by-track

Connect with MusicRadar: via Twitter, Facebook and YouTube

Get MusicRadar straight to your inbox: Sign up for the free weekly newsletter