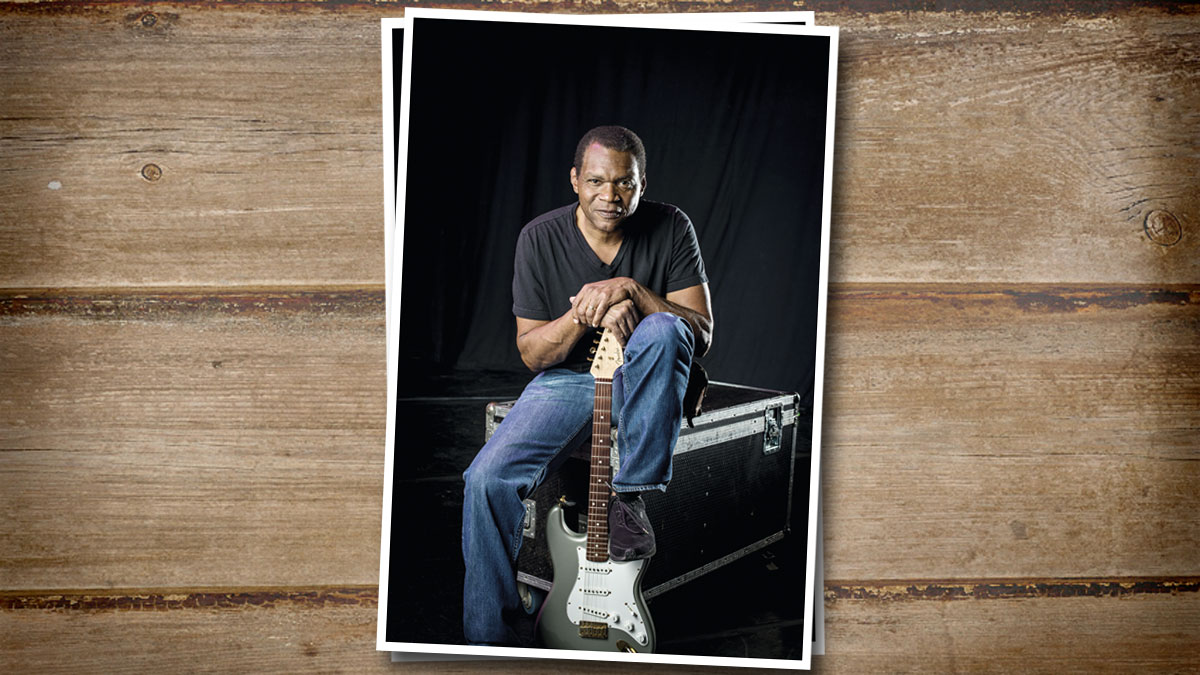

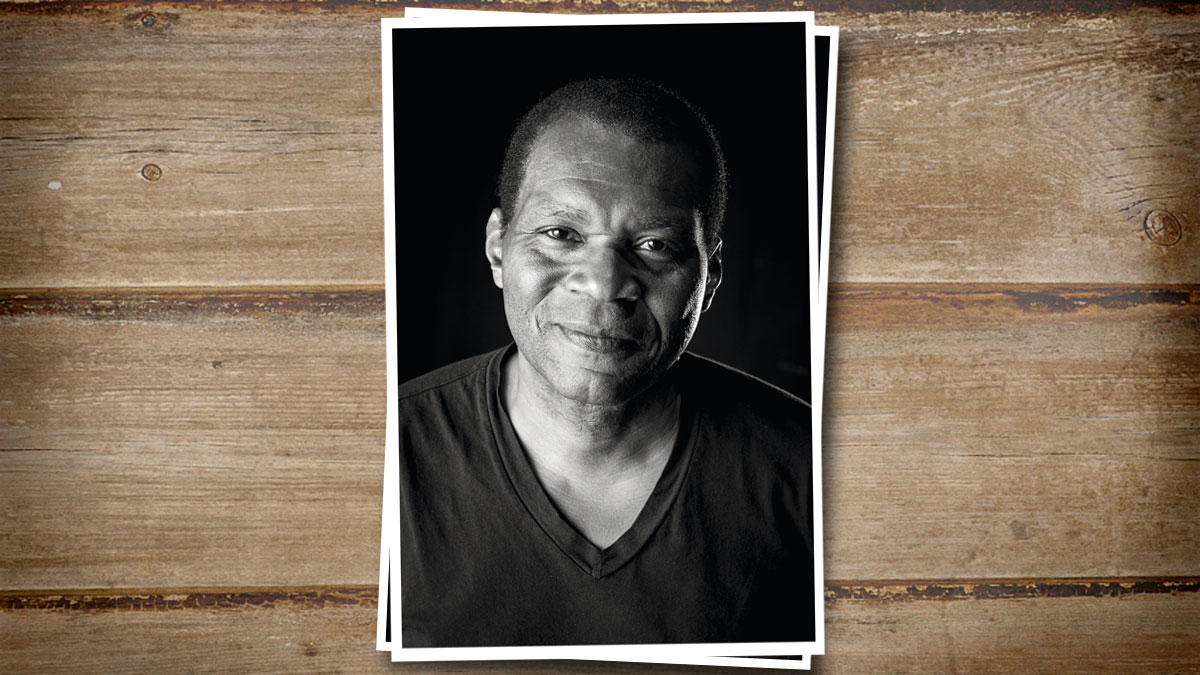

Robert Cray talks heroes, gear and the blues today

An expansive interview with the bluesman

Introduction

Once the new kid on the block, Robert Cray is now firmly recognised as blues aristocracy. Here, he shares memories of Albert Collins, BB King and Stevie Ray Vaughan - and reflects on the state of blues today.

It’s been over 30 years since Robert Cray first blew into view. He rejuvenated the stagnant 80s blues scene and was totally unique among his peers. As Keith Richards once sagely remarked: “He had one foot in the past, and one foot in the future.”

The blues mafia withheld their praise. They saw him as some kind of heretic - a musician who refused to abide by the rules

Clean-cut and strikingly photogenic, Robert Cray fused the grit of older generation blues heroes such as Magic Sam and Otis Rush, with the smooth R&B of OV Wright and Al Green, all topped off by his savage Albert Collins-inspired guitar licks.

He wrote some great songs, too, and blues credibility - if he needed it - quickly arrived when Albert King recorded Phone Booth. Eric Clapton covered Bad Influence, and his early albums, such as Strong Persuader, became musthave additions to any self-respecting record collection. But it wasn’t all plain sailing…

The blues mafia withheld their praise. Cray’s music just wasn’t raw enough for them, and they saw him as some kind of heretic - a musician who refused to abide by the rules. Through it all, however, young Robert kept smiling on, happy to ignore his critics, wailing away and showing off his seductive Gospel-inspired vocals, while honing one of the most distinctive blues guitar tones to come along since John Lee Hooker plugged his Gretsch into a beaten-up Silvertone amp.

Now, 40 years after he and bassist Richard Cousins first put together their band in Portland, Oregon, comes 4 Nights Of Forty Years Live, a live CD and DVD of musical snapshots recorded over the years with Cray’s various bands, plus extracts from four recent shows. Perhaps what is most striking about the footage is just how little has changed - still the same stinging Strat solos, still that same soulful voice.

We recently caught up with Cray to discuss his guitar-playing career so far and took a glimpse at his live rig, too.

Playing with Collins

You started out acting as backup for Albert Collins in the Pacific Midwest around 1976. That must have been a fantastic experience?

“It was a great opportunity to work with one of our heroes, and Albert became like a father figure to us - we were only about 23 years old, young kids, and being around him was great. He showed us the ropes, showed us how to travel and taught us how to all get along on the road.

For a period of about 18 months, whenever Albert was out on the West Coast, we backed him up

“It was before Albert signed with Alligator Records, and it had been a while since the Imperial records he put out. Canned Heat first brought him out to California, and things were good for him for a long time before they started to tail off.

“In 1976, we had just finished a run of four nights at a club, and the owner told us Albert was coming through and needed a backup band. We’d been playing some of his numbers anyway, so we met up, went out for four days, and became good friends.

“After that, for a period of about 18 months, whenever Albert was out on the West Coast, we backed him up. We worked everywhere between Vancouver, British Columbia, and down to San Francisco, where we played the 1977 blues festival.

“Before that, we had worked with Curtis Salgado in Eugene, Oregon. Eugene was a college town of about 100,000 people, and we managed to bring in a lot of blues players who could use it as a stopover gig between Vancouver and San Francisco. So, we had Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, Big Walter Horton, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Hubert Sumlin… All these great people came to town.”

There have always been very obvious echoes of Albert’s playing in your own guitar work. Did you consciously strive to absorb his style, or was it something that happened naturally?

“We were standing alongside him night after night on stage, playing his songs, so it was just natural that we would absorb the way he played, and what he did. He was a big inspiration, and I just loved the way he would dig into the strings with his fingers, picking them really hard, then letting them drop back. His fingers were so hard; they were like picks!

“I’d try to pull off some of his licks, but it was hard. Albert played with his Telecaster tuned to C or D minor tuning and used a capo. For me, [who had been] playing a guitar in normal tuning, the stretches were about a mile long!’”

The Clapton effect

You started playing shows in the UK around the time Eric Clapton recorded Bad Influence. Soon after that, Clapton got up on stage with you at Dingwalls in London. How did it feel to have that kind of recognition?

“I heard that he was coming, because his guitar tech had come in earlier in the afternoon and set up an amp. But, of course, it was great to have Eric up there - a flimsy disc of a couple of numbers came out with Guitar Player.”

I never wanted just to re-do old blues songs, and there are so many influences over what I do

When you first came to the UK in the mid-80s, it was a time of great interest in roots music, and many people saw you as being the ‘saviour of the blues’. How do you feel things have worked out?

“Pretty well, I think - we’re still a working band, out there playing the music that we love. But we were lucky to get out there at a time when there was a lot of interest in our kind of music.”

Praise from the blues aristocracy - BB King, Buddy Guy - came very quickly, but there was a certain amount of hostility in the blues press towards what you were doing. Did that hurt?

“No, I know a lot of bands that play music that they deem to be blues, which is so different from mine. So, if anyone thought that way, I regard it as a problem for them, because I enjoy blues as much as they do, and there’s enough room for everybody out there.

“I never wanted just to re-do old blues songs, and there are so many influences over what I do. I’ve just wanted to write songs that pertain to me and my life - which is what a lot of the old blues songs were about anyway - and let the music breathe, be whatever it happens to be.”

Vaughan and the valley

You played at Alpine Valley the night Stevie Ray Vaughan died. Do you think blues music has lost direction since?

“I’d been looking forward to that night in a big way. I hadn’t seen Stevie for six months, and Jimmie Vaughan was there on the second night, which was great, because we’re really good friends.

I was one of the people that should have been in the helicopter that crashed

“Everybody had a great time jamming on Sweet Home Chicago at the end, but when I got back to my hotel, I had a call from my manager; I was one of the people that should have been in the helicopter that crashed. In fact, it was one of Eric’s crew that had taken my place, the guy who’d helped me on stage with my amplifier at the end of the concert.

“But terrible as it was, I don’t think blues music has changed since Stevie’s death. It’s music that’s always suffered from not being in the mainstream, but at the same time, that aspect of it has always propelled anyone who’s an eager listener to go out and seek it. It’s how I became interested. Like when you’re a young kid and you want to think of something as being your music.

“And I’m still like that - when I’m out on the road, we go and find vinyl shops, see what might be there that I haven’t got. Often, people come up and might want to talk about Muddy Waters records, which were amazing; there were no long guitar solos, but everything was there in just a threeminute song.”

Howlin' for you

Over the years, you’ve mainly recorded your own songs, but you have covered Who’s Been Talkin’ and Sitting On Top Of The World, tracks associated with Howlin’ Wolf. Has he always been a favourite?

Sadly, the Memphis Horns aren’t any more. But I really enjoyed working with those guys

“I’ve always loved Howlin’ Wolf’s songs but sadly, I never got to see him. Richard [Cousins] and Curtis [Salgado] went up to catch a show in Seattle just after we’d been out on the road for four nights, and because I was tired, I stayed home. I always regret that, but it was towards the end of his life and he wasn’t well.”

At one point, you enlarged the band with the Memphis Horns and Tim Kaihatsu playing second guitar. But you always seem to come back to the small format…

“It was expensive to keep that band on the road, but at that time, I think we were making more money, too [laughs]. I like working with a small combo, it’s what I’ve always done, and of course, sadly, the Memphis Horns aren’t any more. But I really enjoyed working with those guys.”

Chuck v Keef

You took part in the Hail! Hail! Rock ’N’ Roll Chuck Berry birthday concert. What was it like working with Chuck?

“That was great, and I had a really good time. But Chuck was giving Keith Richards just the hardest time. Keith was there to pay homage to his hero, but the way Chuck acted was untrusting, especially as he knew Keith. But I think he really wanted to be on top of everything.”

Given your admiration of people such as OV Wright and Al Green, working with Willie Mitchell on the Take Your Shoes Off album must have been a big thrill?

The first time we met BB King was in the early 80s in California, when we’d opened up a show for him

“Yes, it was. Willie came to Nashville where we had already been recording, wrote out the charts, and we cut the song Love Gone To Waste. Then went back to his old studio in Memphis - where he cut all those great records - to finish off the mixing. It was really cool to work with him.”

You shared stages with BB King a lot over the years. How did you first meet?

“The first time we met was in the early 80s in California, when we’d opened up a show for him. BB hadn’t arrived at that time and when I came offstage, I wasn’t allowed in my dressing room. One of his minders kept me out, which made me upset. So, that wasn’t a very good start, but we became really good friends - he was one of the nicest people walking the planet.”

1-2 -345

Your style is one of the most instantly recognisable in the blues arena. You started out on a Gibson ES-345 on the Who’s Been Talkin’ album. Changing to a Strat must have required a whole different technique?

“I actually started out using a Gibson SG Standard, then because I wanted to get those BB King sounds, I put that down and played a 345. That gave me a real deep sound at that point; the 345 was too heavy on the bass end, too bright at the high end.

I’ve since retired my ’64 Strat, but the new ones just play great. I make up my own strings - an 0.011 for the high E through 13, 18, 28, 36, 46.”

“Then I caught Phil Guy playing - Buddy’s brother - using a Fender Super Reverb with the reverb up quite a bit, and a Strat. The sound he was getting really blew me away, and shortly after that I fell in love with my 1964 green Strat; it gave me the sound I wanted and was also so much easier to use working around a microphone stand. After the Gibson 345, with the six-position controls, a Strat with just the three-position switch was so much easier to work!

“I’ve since retired my ’64 Strat, but the new ones just play great. I make up my own strings - an 0.011 for the high E through 13, 18, 28, 36, 46.”

Matchless tone

For a long time, you used Fender amps and then you switched over to Matchless setups. How did that come about?

“We were doing a show in Hollywood opening up for Bonnie Raitt, and I had the chance to try out her guitar player’s setup; I played down by the bridge and the sound through the Matchless just flipped me out.

Some people collect guitars, but I collect amps!

“I still have the Fender Super Reverb and use it for recording sometimes, with a Fender Vibro-King as a second stage amp, but the Matchless Clubman 35 is my main amp - Class A 35 watts with a 4x10 cabinet, and I use two of them. Jimmie Vaughan used the same setup for a while.

“We change the tubes around a bit, experimented doing various things. They’re just great amps. I also use a Magnatone Stereo Vibrato that my guitar tech made for me years back. Some people collect guitars, but I collect amps!”

The Robert Cray Band’s 4 Nights Of 40 Years Live double-CD and DVD is out now on Mascot Records