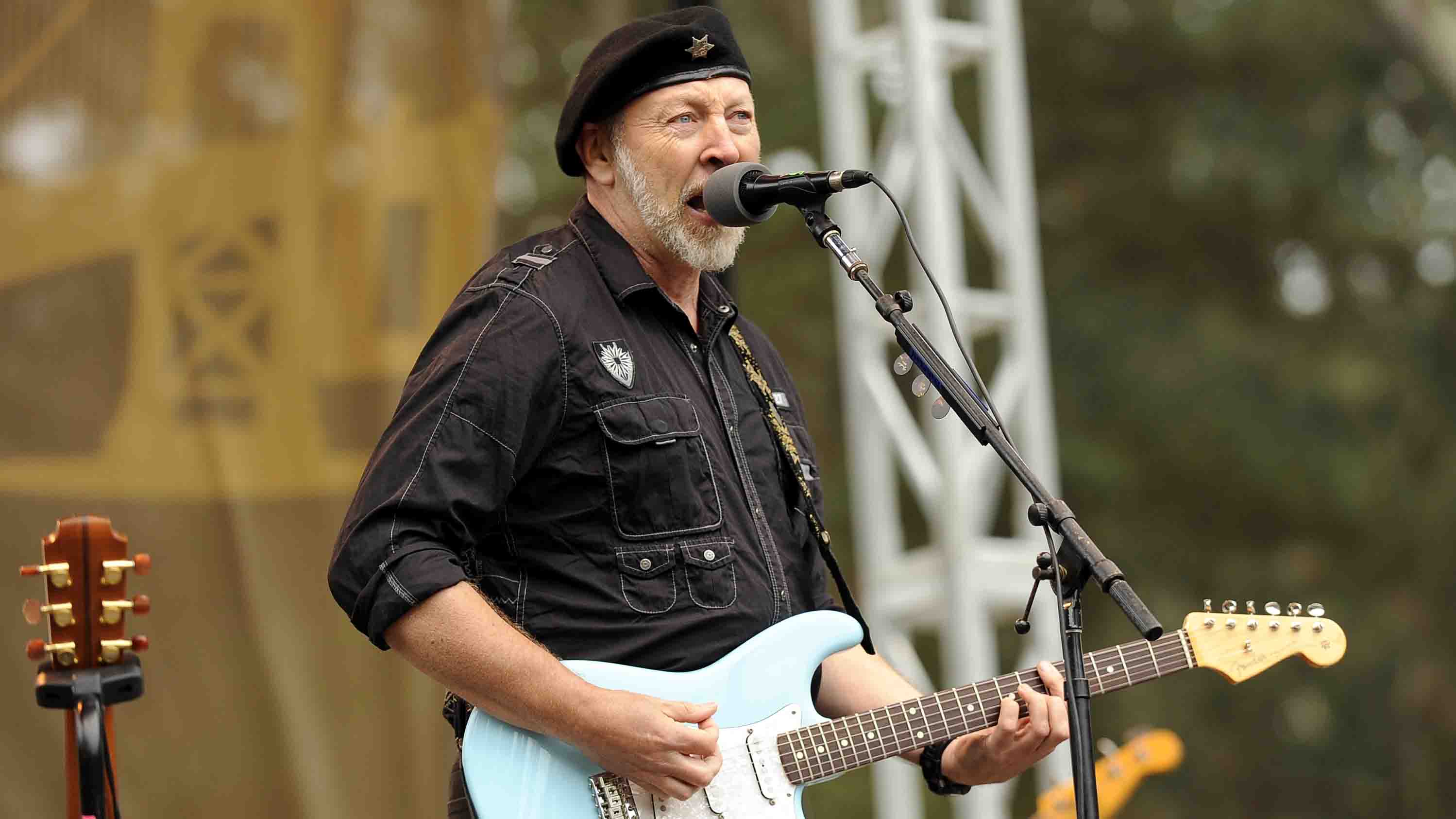

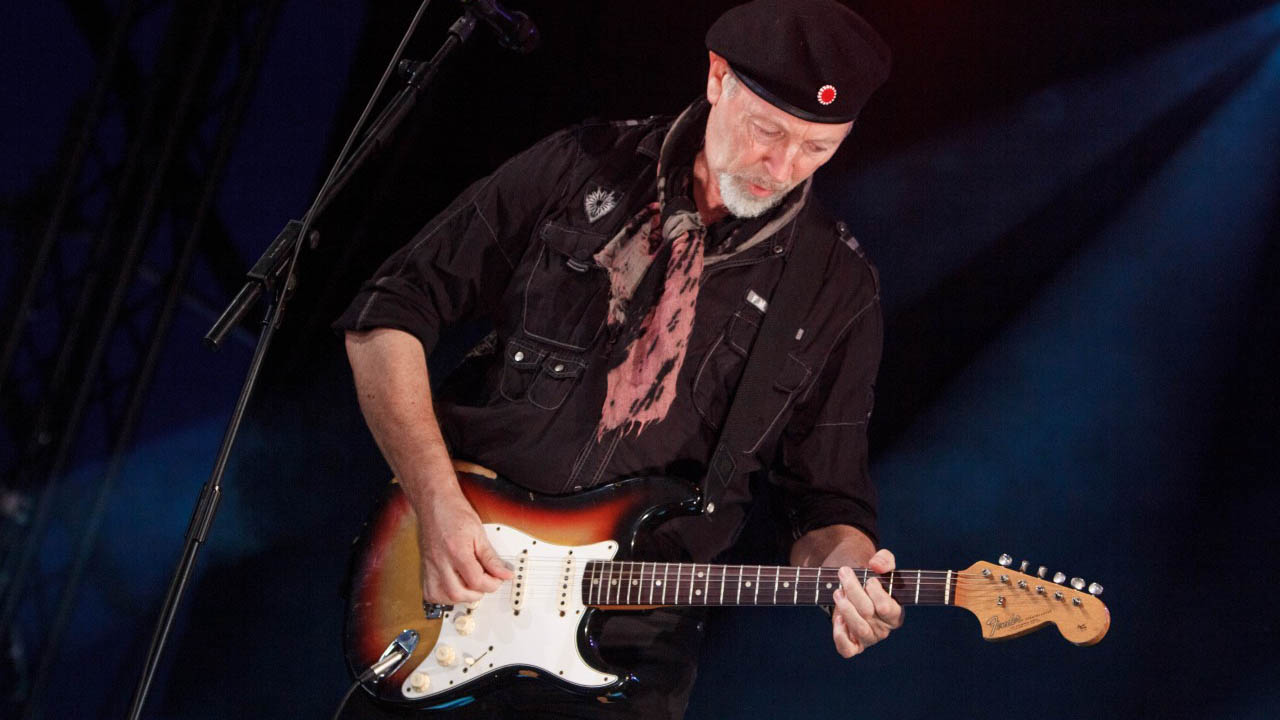

Richard Thompson on new album Still, songwriting and guitar heroes

The folk-rock master talks Hank Marvin, high-end acoustics and being a stationery fetishist

Introduction

It's early on a Thursday morning, the day after Britain got busy melting during the 'hottest day of the year' (so far). There are two crows having a dust-up outside MusicRadar's open window, and a third ambulance in 10 minutes is blasting down the road, siren wailing. “It's noisy where you are,” chuckles the softly spoken man on the other end of our telephone line. “Sounds like they're coming to get you.”

While most people are on their way to work, we're chatting with one of Britain's greatest folk-rock exports, and original Fairport Convention guitarist/vocalist, Richard Thompson OBE. We agree it's too early for interviews, but the critically acclaimed, London-born singer is making it easy on us, if not himself.

“I'm normally an early bird, but I just came back from America, so I'm incredibly jet-lagged. It's a struggle to keep my eyes open right now.”

MusicRadar was brought up proper, so we offer to call back. Sadly, there's no chance - Richard has back to back interviews, and it seems as though the world and his wife want to know about his brilliant new album, Still. In fact, there's already talk that he's written the folk-rock album of 2015.

“You could all be wrong,” he laughs it off, so we read out a few quotes from the glowing reviews of Still that are springing up in print and online, and gush about album opener She Never Could Resist A Winding Road, the groove-laden All Buttoned Up and the free-spirited Beatnik Walking.

“Well, I really like the fact that people get it on some level,” he settles in to the idea. “You make a record and do the best you can. You have hopes that you've done something good, but you never really know until you play it to other people. So I'm delighted if people are getting it in that way. I'm not making music for myself, I'm making music to share with people.”

And if you're wondering whether Richard, an award-wining, honours-laden artist with 16 solo albums (excluding the six albums recorded with ex-wife Linda) under his belt, was working to some grand vision for Still, he wasn't. “It's 12 songs that I had that I felt belonged to each other; they had a commonality and I felt that, together, they'd make an interesting album.”

Here, Richard takes us deeper into his “interesting” new album, talking about the guitar masters he's paid tribute to, and how past demons give him that extra edge.

Master songwriter, stationery fetishist

Do you perform any rituals for getting into the right mindset for writing?

“I have to be off the road for songwriting. If I'm on the road, I'm jotting ideas down, then when I get home I work on them properly. So my routine would probably be to start early, around 7am. I usually start by finishing something, because the last thing I want is to be staring at a cold page.

“I also have to write on Clairefontaine stationery. I'm a stationary fetishist, so everything has to be right before I start. I use loose leaf paper and set two pages side by side to have a large space to write tangentially as well as logically. I'll stop writing at lunchtime, but if it's going well, I'll keep going until the evening.

"Sometimes I like to write away from an instrument, to carry melody in my head where it's not so nailed down and my fingers don't automatically fall into patterns.”

Which song did you write first for Still?

“Probably No Peace No End, although the first song we recorded for the album was Long John Silver. No Peace No End didn't come easily to me, but that's fine, because if it's easy I start questioning whether the song is any good. I wrote all of the songs [for Still] in about two to three months. It sounds prolific, but for six months before that I didn't write anything. Perhaps I was gestating.”

Is songwriting your main gift, or would you say that you're a guitarist first, songwriter second?

“I like to think of them as a package. My main interest is 'the art of song', and into that package, I bring my skills as a guitar player, as a vocalist and as a writer. For me, the good moments in music are taking an electric guitar solo, where I can drift into the zone and almost have an out-of-body experience. The other great moment comes when I'm performing a song and I know I'm reaching a room full of people; that something is being transferred from me to them.”

You credited Bob Dylan with bringing 'smart' lyrics to popular music. A lot of people credit you with writing smart lyrics and storytelling. Where do you begin when writing lyrics?

“The starting point varies. If you only have one way of beginning, you're limiting yourself. It's better to have multiple entry points, like lots of doors into the same room. It's nice to start melodically or lyrically, or start in an abstract way by thinking about particular lines.

“A lot of the time I start writing because I find a good line, and then I have to find a second line that might rhyme. And sometimes in that second or third line there are unexplained things that need to be resolved, so there needs to be more lines to resolve the things I've set up. Ultimately, it's playing around with abstract ideas, with rhymes and the sound of words.”

Timeless influences and guitar heroes

There's something about Beatnik Walking that's reminiscent of Nick Drake's music. Are there any artists who you consider to be timeless influences on your music?

“The biggest influence on my songwriting is traditional music and the people who worked closely to it, like Carolina Oliphant, the Baroness Nairne. She was an aristocrat who reworked local folk songs. Ewan MacColl also - he wrote wonderful, traditional-based songs - and people like Dylan and smart, poet/songwriters like Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell.”

Do you have any influences on your writing outside of music?

“In school we studied [W. B.] Yeats. My father was very interested in poetry and he had [works by] Robert Burns and Walter Scott, who were also songwriters, so I grew up listening to and reading all that stuff. I grew up studying traditional music form - English and Scottish ballads - because I loved it. If you want to know about songwriting, everything you need is there in traditional music.”

You have a monster guitar song on Still called Guitar Heroes, referencing the likes of Django Reinhardt, Hank Marvin and Chuck Berry. Why do they, in particular, stand out for you?

“Guitar Heroes is really a list of the guitar players I was listening to as a kid. There are probably a few guitarists missing, but the song is already eight minutes long!

"In my dad's record collection there was Django and Les Paul, so I was listening to those from the age of three. In my sister's record collection she had rock 'n' roll guitarists like James Burton, and Hank Marvin was probably the reason why every spotty teenager picked up a guitar in the 1960s, myself included.

“I heard Chuck Berry a little bit later. He was making records in the '50s, but we didn't hear him properly in the UK until around 1962/63. Growing up on bad early '50s music, it was kind of a shock hearing [Chuck Berry]. My older sister had the first Bob Dylan album [Bob Dylan, 1962] and she had blues records, too. I finally began to understand that it wasn't out of tune. It was more like an African tuning meets Western tuning. It was edgy.”

Lowden acoustics and respecting the greats

When recording concept song Guitar Heroes, did you use a Maccaferri for the Django part, and Gibsons for the Les Paul and Chuck Berry's parts, and so on?

“I couldn't get my hands on a Maccaferri, which would have been fun to play, so the Django part is played on my Lowden [Jazz Series] signature acoustic. I used a Gibson Super 400 for the Chuck Berry section, a Les Paul for the Les Paul section, a 50s Telecaster for the James Burton section, and a Fender Strat for the Hank Marvin section.

You're known for playing Lowdens and Martins. Are you drawn to high-end acoustics?

“I love the Lowden because it turned out to be a remarkably fine guitar. It's loud, punchy, sounds beautiful and balanced. So yeah, I like high-end guitars but I also like crappy old guitars, too. Sometimes, a small-bodied, old, ratty looking guitar can sound great on record. I hate the cult of high-end guitars in some ways - it all gets a bit precious. The perfect playing and all that… I find it so unemotional.”

What other gear did you use during the writing and recording of Still?

“Because we were recording in Wilco's loft studio [Still was produced by Wilco vocalist/guitarist Jeff Tweedy], which is stuffed with hundreds of guitars and amps, I lost track. I do remember using an old Fender Princeton amp, an old Fender 65 Deluxe [Reverb], a Morgan amp - which I'd never seen before but it's a really great amp - and a Vox AC15.

“As for guitars, I used some unnamed Japanese guitars in places, some old Martin acoustics, and my Lowdens. On the whole, I used the guitar I usually use, which is a [coral-coloured, modified] Fender Strat.”

Keep on, keeping on

After so many decades in the business, how do you get and stay inspired to write?

“Sometimes there's fresh inspiration, sometimes you get angry or feel deeply about something that happens to yourself or your family, and sometimes you trawl backwards into the past and write about things that are unresolved in your life. Life can be hard to decipher and sometimes you think, 'Why did that happen to me?' It might take you 10 or 20 years to figure out the reasons for why things happened, and I think sometimes songwriting really does go back that far.

“You think about an incident and believe that if you write about it, you'll understand it better. It's not really catharsis because that's not the point, but I think catharsis is a by-product of finding these old things that never quite got settled. It's like the Charles Dickens thing: in some ways he had a very disturbing childhood and it keeps coming up again and again in his novels, as an inspirational point for him.”

You've had mostly successes with music throughout the years, but you've tasted the sour side of the industry from time to time. What drives you to keep coming back, to keep making music?

“I love music. I love making music, I love performing music. Perhaps I'm driven by demons from a past life. In a Dickensian sense, things from your childhood can drive you on. They can give you that extra edge.”