Richard Hawley talks Hollow Meadows, broken bones and rare guitar finds

"As long as I'm playing guitar, I'm happy"

Introduction

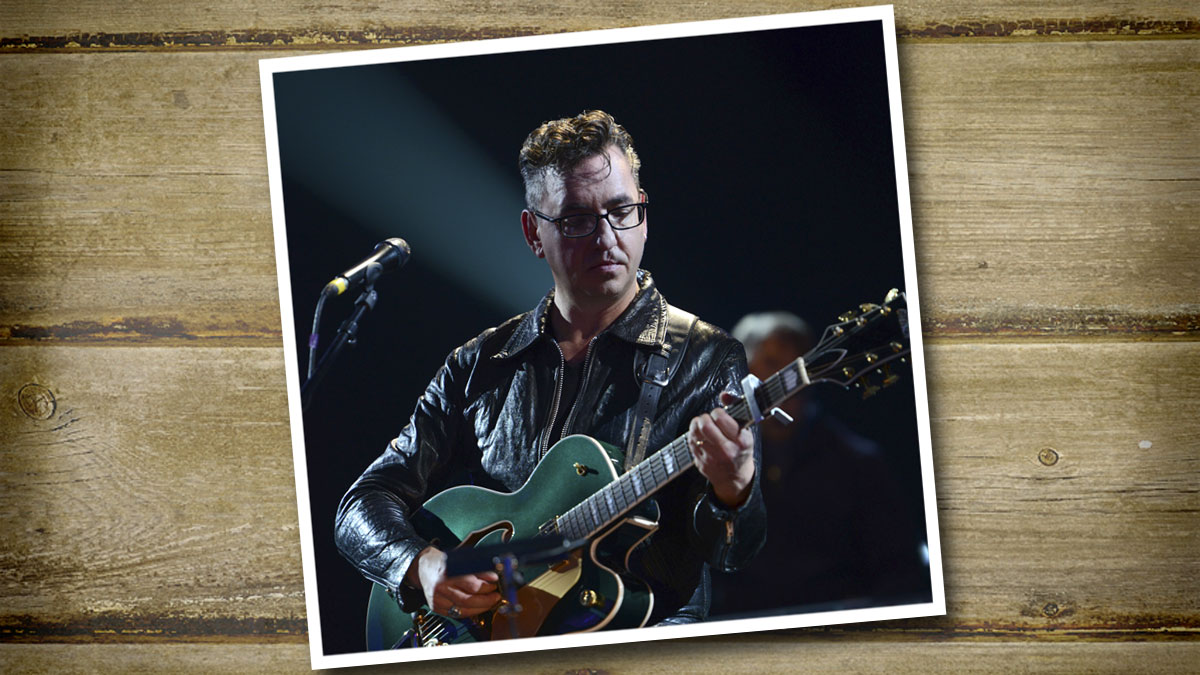

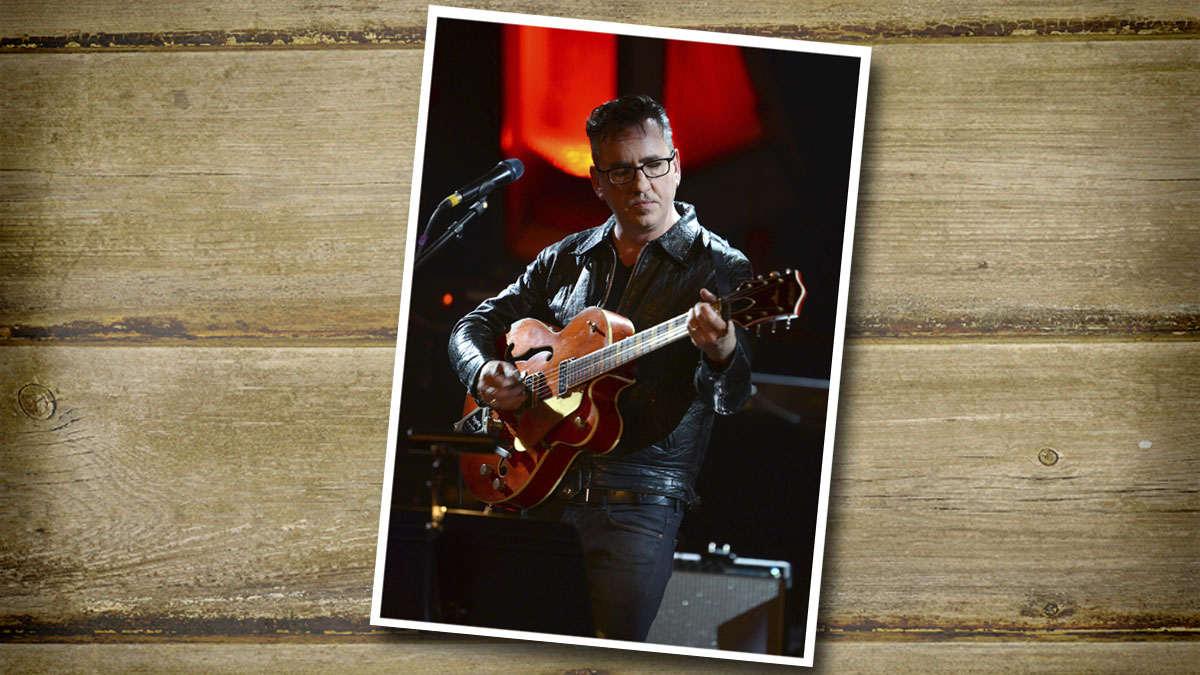

Sheffield songwriter Richard Hawley has a lot to be thankful for with the release of his eighth album, Hollow Meadows. Arthritis threatened to rob him of his ability to play, but an old J-200 and the ‘genie’ of inspiration helped him complete one of 2015’s best records. Here, he tells us why he’s “lonely without a guitar”.

I broke that knuckle on a drummer’s head, trying to stop him stabbing the singer in a tour bus in Birmingham, Alabama

“I broke that knuckle on a drummer’s head, trying to stop him stabbing the singer in a tour bus in Birmingham, Alabama. And continued to do the tour with a broken hand. It’s life, you know.” Richard Hawley, Sheffield’s poet laureate of the Gretsch, is discussing his guitar style, which has had to adapt to a few hard knocks over the years.

As evidence, he holds out a fretting hand that does, let it be said, look like it’s seen some action. On his lap is a 1950 Gibson J-200, on which he’s just finished playing an old Earl Scruggs song called Jimmy Brown The Newsboy, which he learned from his father.

“That’s my dad,” Richard says, showing an old family snap that’s now stored on his phone. “That’s a picture I took of him in ’82, with his pint and his fags. He’s playing an Ibanez acoustic there - I don’t know what model it was. That picture was taken during the steel strike, because my dad had this idea where he got all the bored steelworkers to come and learn to play guitar. So he taught them all to play guitar.”

He taught Richard, too, passing on his Travis-picking skills and a store of beautiful old rockabilly licks, evidence of which you can hear in Hawley’s playing on the J-200 today.

Don't Miss

Rebel rouser

It’s the kind of style that Eddie Cochran and Cliff Gallup had, and all those 50s rebel-rousers who could sound mean as a flick-knife or tender as a broken heart, as the song required.

“I could never get my head round playing with fingerpicks like my dad did, though,” Richard adds. “So I play with [a combination of ] plectrum and fingers, like this. But when I worked with Duane Eddy, I said to him that I couldn’t do it right, but he said, ‘No, Jimmy Burton and Scotty Moore play like that.’”

Hollow Meadows came about because of the physical state that I was in, because I’d broke my leg and I’d f***ed my back up

We’re discussing all this somewhere backstage at Bristol’s Colston Hall, where Richard is performing that evening. He’s currently touring his new album, Hollow Meadows, which sees him return - after the heavier, cosmic rock of Standing At The Sky’s Edge - to a more introspective mood that long-standing fans will be familiar with.

You can hear Scott Walker, Gene Vincent, Duane Eddy and others in its sound - distant echoes from an old jukebox in Hawley’s imagination, perhaps. But, at core, his writing is about the here and now.

“Hollow Meadows came about because of the physical state that I was in, because I’d broke my leg and I’d fucked my back up,” he explains, referring to two debilitating injuries sustained in the space of a year, starting with a fall on stone steps in 2013 .

“And it was to do with trying to write songs and be positive in a very fucking dark place. Without kind of being ‘woe is me’, there was something I was trying to figure out, positively, about things I loved.

“I wasn’t really sure whether it was going to end - whether I’d be able to walk again,” he recalls. “They told me there was a huge percentage that I would never walk again. That kind of scared the shit out of me - it really was quite terrifying. The reality of that just led me to think, ‘What are you actually about, Hawley?’ And a lot of those songs on there are the essence of what I’m about, I guess.”

Love thy neighbour

The result of that soul-searching is an album that is at once intimate and sweeping in scope - its songs a series of open questions concerning the things that matter most in life.

The people that I’ve met, it always seems to happen at the right time when I need them the most

There’s also plenty of fine guitar playing on this album, some of it contributed by Richard’s next-door neighbour - who, handily, is none other than folk-guitar virtuoso Martin Simpson. Outside of the studio, the pair get together round the kitchen table to play guitar as often as touring will allow.

“Martin played on Long Time Down,” Richard explains. “We tried to get out together on this tour, but he’s doing musical workshops, teaching and he’s got his own gigs as well. It’s no secret I love the man - as a man, forget the guitar playing, I just mean as a person. And I just think, sometimes, there must be someone watching over me. The people that I’ve met, it always seems to happen at the right time when I need them the most.”

Richard met Martin four years ago, when worsening arthritis in Hawley’s hands threatened to end his playing career. An experimental course of treatment, involving injections that carried their own health risks, was proposed by a specialist doctor, at which point Richard found himself at the crossroads.

“I had to weigh up the options of what I wanted to do: play another 10 years of guitar, or sit there in crippling pain,” he says. “And I talked to my wife about it, because it’s a serious life issue. And she just agreed with me that I’d be just so miserable if I couldn’t play guitar. It’s the only thing I’m any good at, and I don’t know if that’s any good, either! But it’s one of those things where you go, ‘I’m prepared to take the risk because I don’t want to be unhappy. And I’m not bothered whether I’m playing in my bedroom or on stage, I don’t care. As long as I’m playing guitar, I’m happy.’ The end.”

Pre-war revelations

Thankfully, the injections worked, combatting the worst effects of the disease and allowing Richard to continue playing, and he kept limber by jamming with Martin Simpson.

During their impromptu acoustic sessions, they began talking about a treasured guitar of Richard’s that had been stolen. Simpson, who has many contacts in the vintage-guitar world, kindly decided to help him replace it.

Pre-war guitars - you pick them up, they’re so light. They’re like balsa wood. There’s a voice in them that is unlike any acoustic you’ll get today

“My dad used to have a 60s Gibson J-200 that he left me when he died, and some cunt nicked it,” Richard explains. “I know I’ll probably never see that guitar again. We lose things, you know? It’s in the nature of the world. But I wanted to get another one to redress the balance.

“So Martin ended up trying to help me and find me a J-200. And in the process, he discovered these Gibson L-00s and Martin bar-fret guitars and all this mad stuff. And now we’re both addicted to pre-war guitars. You pick them up, they’re so light. They’re like balsa wood. There’s a voice in them that is unlike any acoustic you’ll get today. Time buys that, if you know what I mean.”

The blonde ’50 J-200 that Richard is now holding was eventually sourced from a vintage-guitar dealer of Martin Simpson’s acquaintance. It’s beautiful, sonorous and takes a capo very well, balancing its big, big bass with sweet treble.

In some sense finding it filled a void, Richard explains - friendship replacing something precious that was stolen. “These are rarer than hen’s teeth,” he adds, playing more chords. “It’s the serial number next to Buddy Holly’s.”

Glorious Gibsons

But, of course, as Richard and Martin made their forays in search of that J-200, as guitarists will, they couldn’t help checking out a lot of other choice vintage gear, some of which Richard bought and which can be heard on Hollow Meadows.

I got a Gibson ES-295, which is the guitar that Scotty Moore played with Elvis on a lot of the Sun stuff

Among the finds was a behemoth Gibson GA-90 amp with a formidable array of six 10-inch speakers and other rarities that were brought into the recording studio built at the bottom of Richard’s garden, which he jokingly dubs ‘Disgracelands’. Here, he cut many of the album’s tracks with long-time musical collaborator, guitarist Shez Sheridan.

“I’ve got a ’63 Gretsch Chet Atkins amp, and it’s got this insane tremolo on it that’s like nothing else I’ve ever heard. This one plays in time with what you play,” Richard says, admiringly. “I also bought a guitar that I’d been after for many, many years from Norman Mitchell, who runs a fantastic guitar shop called Old Hat Guitars in Horncastle [in Lincolnshire].

“It’s a Gibson ES-295, which is the guitar that Scotty Moore played with Elvis on a lot of the Sun stuff. And Norman had got a 1955 one that was virtually mint. And they’re so rare in that condition - because it’s got that gold finish on it and on most of those guitars, it gets a kind of verdigris - you get this weird, cracked, green look. But this one was one that escaped that horror. And with it came a Gibson GA-90 amp.”

Unloved amps

The Gibson amps of the 50s and 60s are a bit of an enigma, we suggest, in the sense that they should be right up there with vintage Fender combos, but somehow have escaped the notice of many players despite often great tone and innovative features, for the era.

“Mate, I really don’t get it,” Richard agrees. “I don’t understand why those amps have escaped history, really. And there’s different ones in the GA Series, different sizes. But the technology of those GA-90s is really interesting, because I think that’s where a lot of bass amps went: there are six tiny little speakers in it, but it’s a motherfucker, it sounds unbelievable.

Half the time, the reason I change guitars every song is because I cannot bear to play a guitar that is out of tune

“You plug the Gibson into that and you know that they were born to be together. You plug anything into it and it just sounds wonderful. Martin Simpson bought a Magnatone amp from the same place.”

As you’d expect, Richard has also brought a few vintage Gibson guitars out on this tour, some of which he’s relied on for a long time, but also some new additions - new to him, at any rate - such as a blonde ES-225 semi, another almost-forgotten gem from Gibson’s past.

“Gordon, my guitar tech, found that for me,” Richard explains. “It’s from a guy from Glossop, whose name I forget for the minute, who deals in vintage Gibsons. And he’d come to Gordon to get it fettled, basically, and Gordon said, ‘Look, this guy’s selling a guitar and I think it’s something that you’d like.’

“But what I loved about it was firstly that I’d never even heard of those - it’s always the 335 that everybody talks about and I do have a couple of those. And then it’s got those dog-ear P-90 pickups, which are to die for. I’ve got an old Epiphone Casino with similar pickups on it. They are balls-out pickups. They’re just insane and, tonally, it’s a wonderful guitar.

“The only problem is that somebody at some point has put a Bigsby on it and they’ve done it really wrong. And so we’ve been battling with that to keep it in tune... I mean, I love it, and between me and Gordon we’ve worked it out. But half the time, the reason I change guitars every song is because I cannot bear to play a guitar that is out of tune. But it’s a really beautiful guitar - the neck is wonderful.”

Avoiding the genie's eye

Given that Richard has such a nice selection of guitars, we ask which he prefers to write on. But outside of an old Slovenian acoustic his wife, Helen, found in a junk shop for £20, he says he doesn’t tend to follow a fixed pattern, or rely on any particular instruments as totems to inspiration.

I have a great horror that the genie, the song fairy, if I ever look her in the eye, then she’ll disappear and leave me

“Songs just happen,” he reflects, “and the words just come out. I used to think that made it less of a song, if I didn’t think about it. But if you just let it flow through you, literally… It’s the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ synapses of your brain. You just have to keep the ‘yes’ ones going. I guess doing shitloads of acid did that for me [laughs]. It’s like the lyrics of For Your Lover Give Some Time,” he adds, more seriously, and sings a bar or two:

“It was your birthday yesterday/ I gave a gift that almost took your breath away/ but to be honest, I nearly left it on the train/ for your lover give some time…”

“And that just happened and I wrote it in like, 10 minutes… I think they’re probably my best words I’ve ever written. But I didn’t think about it at all: ‘I’ll give up these cigarettes, stay at home and watch you mend the tear in your dress…’, stuff like that.

“And I think: who the fuck wrote that? Was that me? Basically, don’t look the genie in the eye. Ever. I have a great horror that the genie, the song fairy, if I ever look her in the eye, then she’ll disappear and leave me. So it’s about hitting the bullseye without aiming for it.

To England, where my heart lies

“I know writers like Nick Cave, for example, who goes into his special work place and he works from dawn to dusk on stuff. But I can’t do that. I’ve never had a doubt that an idea will come, though - because anybody who’s a vaguely intelligent person can write a song. It’s possible.

Heart Of Oak was doing my head in because it was like a Rubik’s Cube that I just couldn’t figure out

“The thing is not to over-egg it. And if the reasons why you write a song are all about, ‘I want to be famous, I want to be successful, driving a limo’ and stuff like that, you’ll probably be a songwriter - but I bet all of your songs are going to be fucking shit,” he concludes.

Still, sometimes some patience with the muse is called for, as with the fine track Heart Of Oak from the new album. It has some of the epic character of Bowie’s Heroes, but a more tender, humble quality, too. Live, that evening, Richard plays electric on it with a kind of 60s guitar-hero style - taking a wide stance and carving air nice and loud, unhurried. But the track took some time taking form, initially, he says.

“That actually was an older song - something that I wrote, can’t remember how long before,” he recalls. “But it was one of those that pissed me off, because I’d recorded it about three or four times and it was doing my head in because it was like a Rubik’s Cube that I just couldn’t figure out. And it was inspired by [folk singer] Norma Waterson, that song - about something that’s quintessentially English but isn’t like a bad thing.

“Often English people think if they’re in any way patriotic that it’s this fascist kind of flag-waving thing. But there are a lot of things that are beautiful and wonderful about England that are not anything whatsoever to do with that. And there’s a lot in there that’s about people who unselfishly nurture things, for no reward at all - it’s just the fact that they care.”

Richard Hawley plays Meltdown Festival on 16 June and Glastonbury on 24 June.

Don't Miss

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.