On 4 February 1970, then Rolling Stone managing editor John Burks was invited by Jimi Hendrix's manager, Michael Jeffrey, to interview the guitar star in New York City. At the time, Hendrix was in a period of transition, having disbanded the original Jimi Hendrix Experience to experiment with the band Band Sun And Rainbows, which had morphed into Band Of Gypsys (a trio that included Experience drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Buddy Cox).

Although both Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding were on hand during the interview, instigated by Jeffrey to trumpet what was supposed to be a reunion of the original Jimi Hendrix Experience, Hendrix's head was apparently otherwise - he would soon go on the road with only Mitchell and Cox. (Redding would learn that he was replaced from Mitchell's girlfriend.)

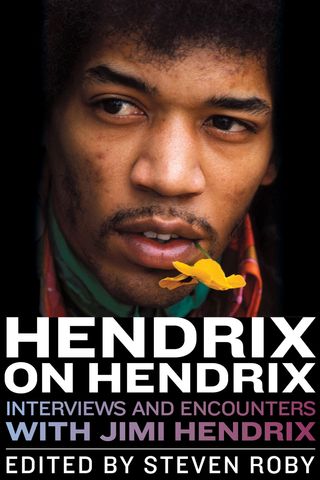

The following interview excerpt, titled The End Of A Big Long Fairy Tale, appeared in parts in Rolling Stone in 1970 and in a fuller form in Guitar Player magazine in 1975. It is taken from the forthcoming book, Hendrix On Hendrix: Interviews And Encounters With Jimi Hendrix by Steven Roby. The book will be published on 1 October 2012 by Chicago Review Press. You can pre-order the book at Amazon.

When you put together a song, does it just come to you, or is it a process where you sit down with your guitar or at a piano, starting from ten in the morning?

"The music I might hear I can't get on the guitar. It's a thing of just laying around daydreaming or something. You're hearing all this music, and you just can't get it on the guitar. As a matter of fact, if you pick up your guitar and just try to play, it spoils the whole thing. I can't play the guitar that well to get all this music together, so I just lay around. I wish I could have learned how to write for instruments. I'm going to get into that next, I guess."

So for something like Foxey Lady, you first hear the music and then arrive at the words for the song?

"It all depends. On Foxey Lady, we just started playing actually, and set up a microphone, and I had these words [laughs]. With Voodoo Child (Slight Return) somebody was filming when we started doing that. We did that about three times because they wanted to film us in the studio, to make us [imitates a pompous voice] 'Make it look like you're recording boys'—one of them scenes, you know, so 'Okay, let's play this in E; now a-one and-a-two and-a-three,' and then we went into Voodoo Child."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

When I hear Mitch churning away and you really blowing on top and the bass gets really free, the whole approach almost sounds like avant-garde jazz.

"Well, that's because that's where it's coming from—the drumming."

Do you dig any avant-garde jazz players?

"Yeah, when we went to Sweden and heard some of those cats we'd never heard before. These cats were actually in little country clubs and little caves blowing some sounds that, you know, you barely imagine. Guys from Sweden, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, or Stockholm. Every once in a while they start going like a wave. They get into each other every once in a while within their personalities, and the party last night, or the hangover [laughs], and the evil starts pulling them away again. You can hear it start to go away. Then it starts getting together again. It's like a wave, I guess, coming in and out."

For your own musical kicks, where's the best place to play?

"I like after-hour jams at a small place like a club. Then you get another feeling. You get off in another way with all those people there. You get another feeling, and you mix it in with something else that you get. It's not the spotlights, just the people."

How are those two experiences different, this thing you get from the audiences?

"I get more of a dreamy thing from the audience—it's more of a thing that you go up into. You get into such a pitch sometimes that you go up into another thing. You don't forget about the audience, but you forget about all the paranoia, that thing where you're saying, 'Oh gosh, I'm on stage—what am I going to do now?' Then you go into this other thing, and it turns out to be like almost like a play in certain ways."

You don't kick in many amps any more or light guitars on fire.

"Maybe I was just noticing the guitar for a change. Maybe."

Was that a conscious decision?

"Oh, I don't know. It's like it's the end of a beginning. I figure that Madison Square Garden was like the end of a big long fairy tale, which is great. It's the best thing I could possibly have come up with. The band was out of sight as far as I'm concerned."

But what happened to you?

"It was just something where the head changes, just going through changes. I really couldn't tell, to tell the truth. I was very tired. You know, sometimes there's a lot of things that add up in your head about this and that. And they hit you at a very peculiar time, which happened to be at that peace rally, and here I am fighting the biggest war I've ever fought in my life—inside, you know? And like that wasn't the place to do it, so I just unmasked appearances."

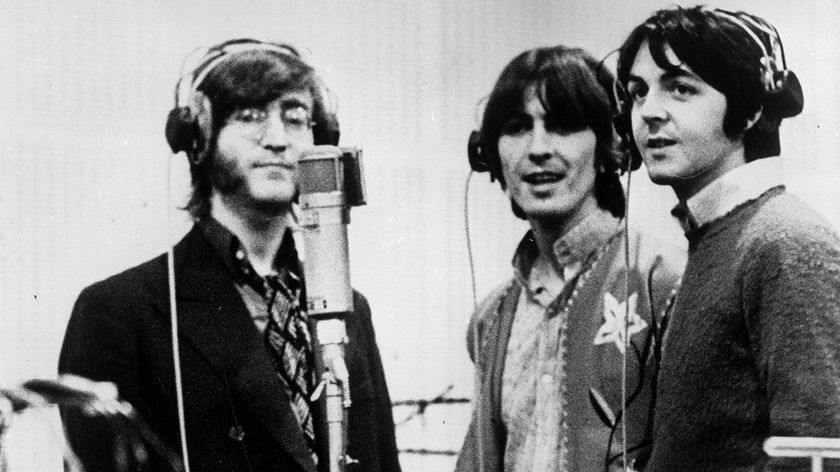

Jimi Hendrix at Heathrow Airport, 27 August 1970. © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

How much part do you play in the production of your albums? For example, did you produce your first [Are You Experienced]?

"No, it was Chas Chandler and Eddie Kramer who mostly worked on that stuff. Eddie was the engineer, and Chas as producer mainly kept things together."

The last record [Electric Ladyland] listed you as producer. Did you do the whole thing?

"No, well, like Eddie Kramer and myself. All I did was just be there and make sure the right songs were there, and the sound was there. We wanted a particular sound. It got lost in the cutting room, because we went on tour right before we finished. I heard it, and I think the sound of it is very cloudy."

You did All Along The Watchtower on the last one. Is there anything else that you'd like to record by Bob Dylan?

"Oh yeah. I like that one that goes, 'Please help me in my weakness' [Drifter's Escape]. That was groovy. I'd like to do that. I like his Blonde On Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited. His country stuff is nice too, at certain times. It's quieter, you know."

Your recording of Watchtower really turned me on to that song when Dylan didn't.

"Well, that's reflections lie the mirror. [Laughs] Remember that 'roomful of mirrors'? That's a song, a recording that we're trying to do, but I don't think we'll ever finish that. I hope not. It's about trying to get out of this roomful of mirrors."

Why can't you finish it?

[Imitates prissy voice] "Well, you see, I'm going through this health kick, you see. I'm heavy on wheat germ, but, you know what I mean [laughs]—I don't know why." [Takes a pencil and writes something].

You're not what I'd call a country guitar player.

"Thank you."

Hendrix performs at a street concert in Harlem, 9 August 1969. © Douglas Kent Hall/ZUMA/Corbis

You consider that a compliment?

"It would be if I was a country guitar player. That would be another step."

Are you listening to bands like that doing country, like the Flying Burrito Brothers?

"Who's the guitar player for the Burrito Brothers? That guy plays. I dig him. He's really marvelous with a guitar. That's what makes me listen to that, is the music."

It's sweet. It's got that thing to it.

[In a deep drawl] "'Hello walls.' [Laughs] You hear that one, Hello Walls? Hillbilly Heaven."

Remember Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys?

[Laughs] "I dig them. The Grand Ole Opry used to come on, and I used to watch that. They used to have some pretty heavy cats, heavy guitar players."

Which musicians do you go out of your way to hear?

"Nina Simone and Mountain. I dig them."

What about a group like the McCoys?

[Sings intro to Hang On Sloopy, which featured Rick Derringer on guitar.] "Yeah, that guitar player's great."

Were you really rehearsing with Band Of Gypsys 12 to 18 hours a day?

"Yeah, we used to go and jam actually. We'd say 'rehearsing' just to make it sound, you know, official. We were just getting off; that's all. Not really 18 hours—say about 12 or 14 maybe [laughs]. The longest we [the Experience] ever played together is going on stage. We played about two and a half hours, almost three hours one time. We made sounds. People make sounds when they clap. So we make sounds back. I like electric sounds, feedback and so forth, static."

Are you going to do a single as well as an LP?

"We might have one from the other thing coming out soon. I don't know about the Experience though. All these record companies, they want singles. But you don't just sit there and say, 'Let's make a track, let's make a single or something.' We're not going to do that. We don't do that."

Creedence Clearwater Revival does that until they have enough for a record, like in the old days.

"Well, that's the old days. I consider us more musicians. More in the minds of musicians, you know?"

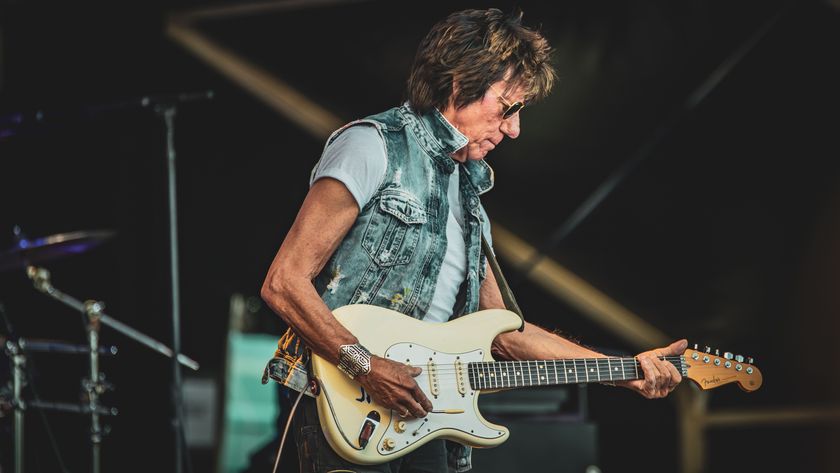

Performing at the Isle Of Wight Festival, 30 August 1970. © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

But singles can make some bread, can't they?

"Well, that's why they do them. But they take it after. You'll have a whole planned-out LP, and all of a sudden, they'll make, for instance, Crosstown Traffic a single, and that's coming out of nowhere, out of a whole other set. See, that LP was in certain ways of thinking; the sides we played on in order for certain reasons. And then it's almost like a sin for them to take out something in the middle of all that and make that a single, and represent us at that particular time because they think they can make more money. They always take out the wrong ones."

How often will you space these concerts with the Experience so that you won't feel hemmed in?

"As often as we three agree to it. I'd like for it to be permanent."

Have you given any thought to touring with the Experience as the basic unit, but bringing along other people? Or would that be too confusing?

"No, it shouldn't be. Maybe I'm the evil one, right [laughs]. But there isn't any reason for it to be like that. I even want the name to be Experience anyway, and still be this mish-mash moosh-mash between Madame Flipflop and Her Ha-monite [sic] Social Workers."

It's a nice name.

"It's a nice game. No, like about putting other groups on the tour, like our friends—I don't know about that right now; not at a stage like this, because we're in the process of getting our own thing together as far as a three piece group. But eventually, we have time on the side to play with friends. That's why I'll probably be jamming with Buddy [Miles] and Billy [Cox]; probably be recording, too, on the side, and they'll be doing the same."

Do you ever think in terms of going out with a dozen people?

"I like Stevie Winwood; he's one of those dozen people. But things don't have to be official all the time. Things don't have to be formal for jams and stuff. But I haven't had a chance to get in contact with him."

Ever think about getting other guitar players into your trip?

"Oh yeah. Well, I heard Duane Eddy came into town this morning [laughs]. He was groovy."

Have you jammed with Larry Coryell and Sonny Sharrock and people like that?

"Larry and I had like swift jams down at The Scene. Every once in a while we would finally get a chance to get together. But I haven't had a chance to really play with him, not lately anyway. I sort of miss that."

Do you listen to them?

"I like Larry Coryell, yeah."

Better than others?

"Oh, not better. Who's this other guy? I think I've heard some of his things."

He's all over the guitar. Sometimes it sounds like it's not too orderly.

"Sounds like someone we know, huh [laughs]?"

Reprinted with permission from Hendrix on Hendrix by Steven Roby. Text copyright 2012 Steven Roby. Published by Chicago Review Press (distributed by IPG). Available 1 October 2012.

The End of a Big Long Fairy Tale, by John Burks, copyright © 2011, New Bay Media, LLC, 78385-1x:0611AS.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)

“We’re looking at the movie going, ‘Urgh! It’s kinda cheesy. I don’t know if this is going to work”: How Chris Hayes wrote Huey Lewis and the News’ Back To The Future hit Power Of Love in his pyjamas

“I thought it’d be a big deal, but I was a bit taken aback by just how much of a big deal it was”: Noel Gallagher finally speaks about Oasis ticket chaos