Randy Bachman on classic Guess Who/Bachman-Turner Overdrive hits

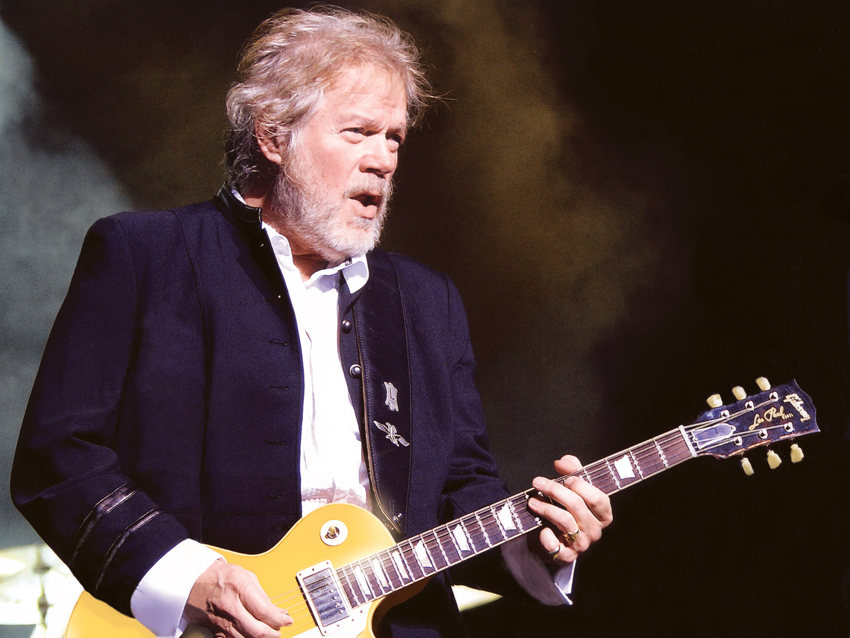

"No matter what anybody tells you, you never know what's going to be a hit," says Randy Bachman, the legendary Canadian singer and guitarist who has written an impressive number of long-standing radio gems, including a couple of chart-toppers for his two former groups, The Guess Who and Bachman-Turner Overdrive.

Expanding on that point, Bachman says, "OK, you always believe something you’re written is a hit. In your own mind it is; otherwise, you wouldn’t want to put it out there. The trick is to convince people, particularly the folks at radio, that your song is a hit. You take your feelings and your melodies and you put them together into something that you think people are going to wanna hear and sing. After that, you have to believe that distant dream that there really is a Santa Claus or Tooth Fairy, who will come along and help make it happen."

And when it does? "When it does, it's Santa Clause and the Tooth Fairy wrapped up in one," he says with a laugh.

Before forming Bachman-Turner Overdrive in 1973, Bachman led The Guess Who from the mid-'60s until he quit the group in the spring of 1970. It was in that band that he formed a writing partnership with lead singer Burton Cummings. Their personal alliance was, at times, marked with tension – "Burton was much younger than me, so I tried to look out for him. After a while, that wasn't gonna fly anymore" – but when it came to writing songs, Bachman says that he and Cummings worked surprisingly well together.

"It was fast and easy," he notes. "We’d throw out lines and say, ‘That’s lousy. I hate that,’ but there’d be no offense. ‘Here’s another one.’ ‘Oh, I love that.’ We’d throw songs together in five, 10 or 15 minutes. He’d write a really great song, and I’d say, ‘It falls apart here.’ Then I’d write something, and he’d say, ‘That’s where you have some problems.’ We’d put our ideas together, put ‘em in the same key, and bang! – we had a song.”

Since 1983, there have been several Guess Who reunions featuring Bachman and Cummings, along with a 2007 album by the duo called Jukebox. Bachman claims that any personal problems between him and his onetime partner – and with any past group members, for that matter – are long forgotten.

“Every band has its drama," he says. "And when you leave any relationship, whether it’s boy-girl or you run away from home, or if you leave your band or your football team, you’ve gotta get up the next day and go make it happen, and sometimes you’re going up against your old teammates. There can be rivalry and hard feelings, but you take the hit and move on. After a while, though, the hard feelings vanish; you can’t stay mad at people forever.”

Bachman recounts his past Guess Who/Bachman-Turner Overdrive hits on the recently released DVD, Vinyl Tap Tour: Every Song Tells A Story (available at Amazon), and on the following pages, he runs down five of his best-loved numbers.

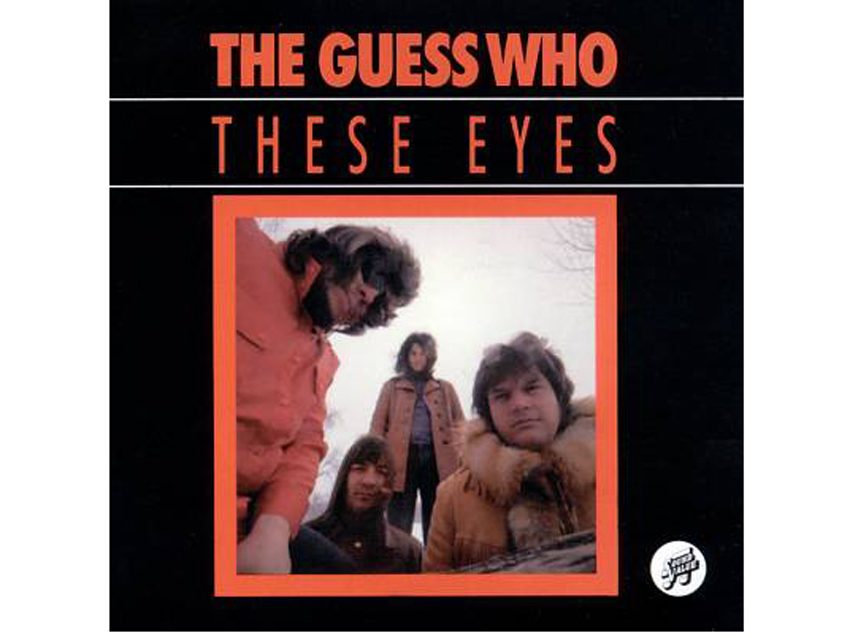

These Eyes

“I was at a Joni Mitchell concert in Canada, and in walked a beautiful brunette. I took her home, asked her for a date for the next night, and she said yes. When I went to her house to pick her up, she wasn’t ready. There was a piano in the next room, so I started playing around to kill some time. A chord pattern came to me – I wanted to call it These Arms because she was late, and I wanted to hold her.

“When I showed it to Burton, he said, ‘That’s really great, but These Arms doesn’t go anywhere; it goes too fast. Let’s call it These Eyes.’ He sang, ‘These eyes cry every night, these arms long to hold you.’ We moved the lines around, wrote it in about 15 minutes, and it became a huge million-selling hit for us. It began our string of Bachman-Cummings collaborations.

“The recording was very easy – 10 or 15 minutes. Burton was a great double tracker with his voice. You can’t even tell his vocals are double-tracked. Same with my guitars – they’re double-tracked, too. We did it at Phil Ramone’s A&R Studios in New York. Jack Richardson was the producer, and Phil was the engineer and kind of co-producer. The strings and arrangements took no time at all. Phil was great at working all that out.”

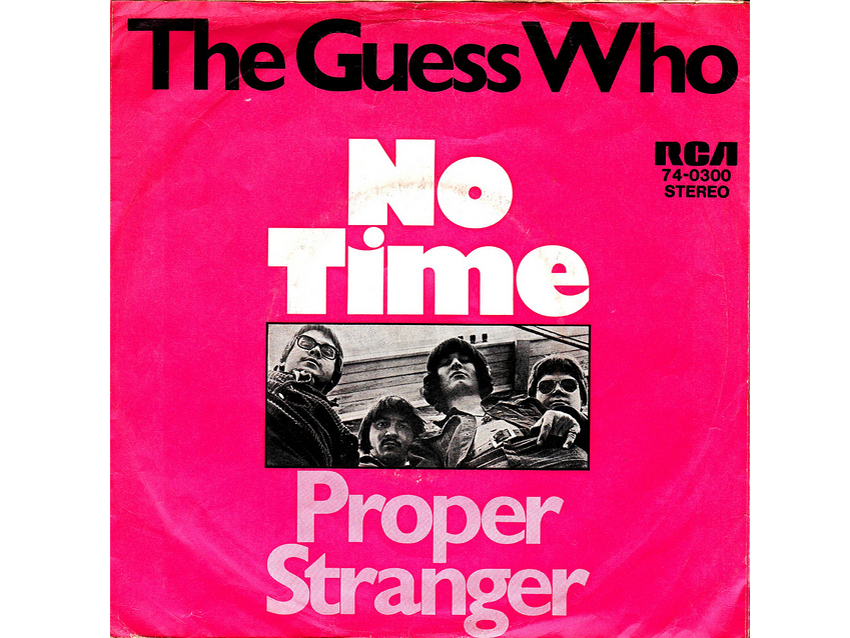

No Time

“Neil Young came to Winnipeg and played us the first Buffalo Springfield album. After that, that’s all I wanted to do – blazing guitars and kind of country harmonies. I had the Buffalo Springfield album and listened to the songs Rock & Roll Woman and Hung Upside Down. I took Stephen Stills’ guitar licks, made them my own and worked out a pretty cool guitar line.

“Burton and I sang ‘No time left for you’ in that kind of country/Buffalo Springfield or Poco way. So yeah, it is a tough song that has a tender side. It was a great progression to get us out of Laughing or No Time of Undun into something like American Woman, which was almost like heavy metal.”

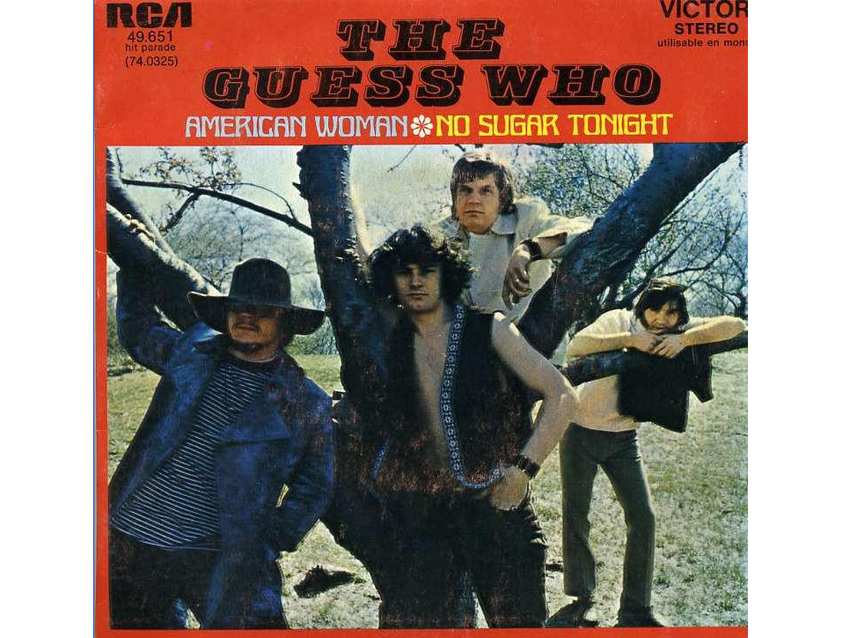

American Woman

“My first number one in the States. This came out of a jam at a curling rink in Kitchener-Waterloo, which is outside of Toronto. We were playing a gig and I broke a string. Because I didn’t have a guitar tech, I had to change my string right there on stage. The band took a break, and while I was tuning up I started to play this riff. The whole crowd stood up, so they could tell it was something. The band came back, and we started playing the riff over and over.

“We did this for about three or four minutes, and finally I yelled out to Burton, ‘Sing something!’ He started singing, ‘American woman, stay away from me,’ and all at once that became the song. There’s an urban myth on Wikipedia about a kid having a cassette recorder that night, but I never saw a kid or a cassette recorder. That never happened. But I remembered the riff. I might’ve changed it a bit, but I did remember what I played. That was easy.

“The guitar I used on the recording was a 1959 Les Paul Special with a Bigsby vibrato. I had played violin from the ages of five to 14, and I always wanted to make a guitar sound like a violin somehow. A guy named Gar Gillis – Garnet Gillis – made us our amps, so that’s what I used, Garnet amps. He made me a preamp that got a really great tube distortion, and it kind of gave me that violin/cello sound. So I plugged that into my amp and it worked great. It’s a very smooth sound, like honey.

“It’s double-tracked on American Woman, the lead playing, and you can’t even tell. I came up with the main line very quickly. I just plugged in and started playing what I would play if I had a violin. Boom – it was right there. I didn’t want it to sound like something you’d play on a guitar, something more bluesy or staccato; I wanted that violin or cello line. Everybody looked at me like, ‘Wow! That’s such a smooth line.’ It worked well with the guitar riff, which is very choppy.

“The message to the song came from us almost being drafted. We were crossing into America and we had green cards, so we ran back to Canada and turned the cards back in. ‘American woman, stay away from me' was really the Statue Of Liberty and the 'Uncle Sam Wants You' poster. It wasn’t a woman on the street; it was us saying, ‘Wow, we don’t want your war machines, we don’t want your ghetto scenes.’

“I love Lenny Kravitz’s version. He took it and made it his own. We were doing a Much Music awards thing together, and I asked him why he didn’t play my guitar solo. He looked at me and said, ‘You played it, but I didn’t know how to get the sound.’ I got one of those little units called a Herzog and sent it to him. Now he can get the sound.” [Laughs]

Takin' Care Of Buisness

“I had this one when I was still in The Guess Who. It was called White Collar Worker, and it was a direct copy of Paperback Writer. The whole song was supposed to stop and we’d sing, ‘White collar worker,’ just like ‘Paperback writer.’ Burton didn’t like that and neither did The Guess Who. Neither did BTO.

“The song kind of hung around. The verses were the same, though – ‘You get up every morning from the alarm clock’s warning, take the 5:15 into the city.’ I had it sitting around for five years. One night I was on stage with BTO, and Fred Turner lost his voice. I had heard a DJ on the way to the gig say, ‘This is Daryl B on CFOX radio, and we’re takin’ care of business.’ I went, ‘Wow, that’s a song title!’

"On stage that night, desperate for a song to sing ‘cause Fred had lost his voice, I pulled out my lyrics to White Collar Worker and started to sing, ‘Takin’ care of business’ where I used to sing, ‘’White collar worker.’ It fit together with no speed bump at all. We played the song for 20 minutes, finished the gig, we recorded it two weeks later, and it became a hit.

“The chords came together so quickly. The original song had something like 12 chords, but I couldn’t show that to the band on stage. So I turned to the guys and said, ‘Play C, B-flat and F over and over. I’m doing a new song.’ They didn’t know what was going on. When it came together, it was one of the most magical moments of my life. To play a song I’d started in 1967 and finish it on stage in front of 400 people singing and dancing, that’s something you can’t plan on.

“In the guitar solo, there’s a bit of me copying John Lennon’s guitar solo from You Can’t Do That. Listen to what I do and what Lennon did in the middle of his solo – it’s an inverted seventh chord, played like a trill. Before I went in to produce BTO, I would always go and listen to Chuck Berry and maybe two or three Beatles records. So I took that one little riff from the You Can’t Do That solo and built a whole thing out of it. I never told anybody that before. [Laughs] I’m copying John Lennon.

“I saw Priscilla Presley talking about the song on TV. She said that she was going to the airport in LA with Elvis, and he heard the song on the radio. He said, ‘Turn that up. I want that as my theme.’ He adopted it and now it’s on his tombstone. Apparently, there’s a version of him playing the song with his band in Vegas, at one of his rehearsals. It’s buried in the archives somewhere. Man, I’d love to hear that.”

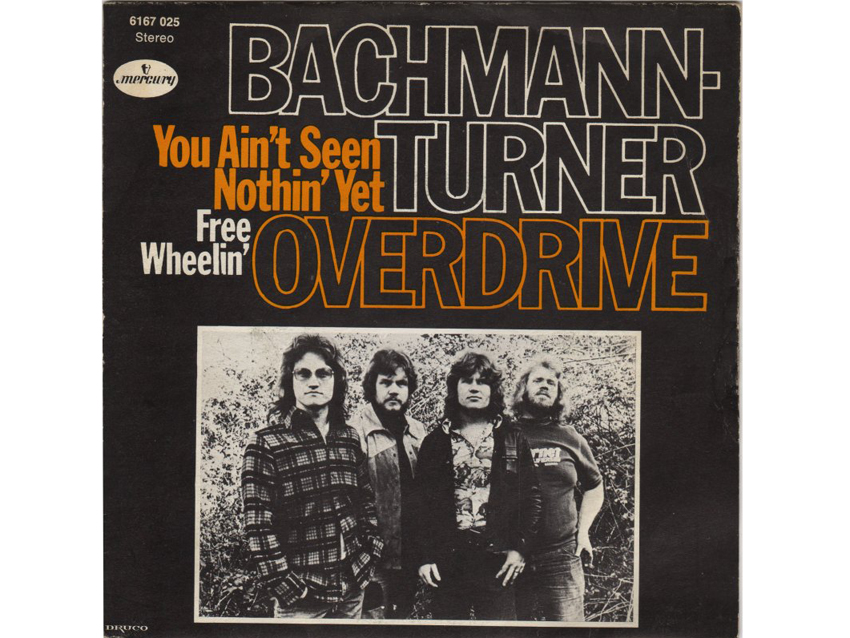

You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet

“It was nice to go to number one with this one. Funny thing was, it wasn’t even supposed to be a song on an album; it was a reject. I stuttered over it and sent it to my brother as a joke. He stuttered, and I wanted to give him a laugh. The head of our label heard it and said, ‘I want to put it on the album. It’s charming.’ I said, ‘No way. It’s a piece of junk, the guitars are out of tune, and besides, it’s a joke.’ I didn’t even know what the song was about.

“We put it out, it went right to number one in 22 countries and sold millions of copies. It proved to me that I know nothing about the business. You can’t pick a hit, you can't plan it – it just happens on its own. You play around, goof around, and then suddenly everybody loves it.

“It might sound like a keyboard on the track, but that’s a guitar, my white Stratocaster. It’s out of tune, so I ran it through a fuzztone and a Leslie speaker, and I put a repeat tape echo on it so you wouldn’t hear how bad it sounds.

“The song has a nice legacy. Two years ago, I got an award from the American Stutterers Association, who named it the “best stuttering song of all time.’ It beat out Benny And The Jets and My Generation. I’ve got the award at home, and I’m very proud of it. After the song came out, my brother stopped stuttering. So for that to happen and then to get the award really makes me proud and happy.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.