Prog-rock production legend Eddy Offord looks back on his career

Eddy Offord loved making records in the '70s. The producer and engineer, whose work with progressive rock pioneers Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer landed both bands at the top of international pop charts, recalls the time period as one that yielded unrivaled exploration and creativity.

"We had a lot of freedom in the '70s as far as interference from record company people," he says. "They would come by occasionally, but they didn’t say anything about the songs or what we were doing. The record companies got what they were given, and that was that."

The nightlife, too, wasn't bad. Swinging London still had some swing, and at the end of a session, Offord and various band members would hit the clubs. "There would be Mick Jagger or Pete Townshend," he says. "Everybody was friendly – ‘Hey, what are you working on?’ It was fun. It might have been competitive, but there was also a joyous spirit in the air."

During much of the '70s, Offord was practically a lodger at London's Advision Studios. The facility was originally built for recording voiceovers and TV jingles, but its expansive rooms, one of which was able to house a 60-piece orchestra, proved welcoming to keyboardists such as Keith Emerson, whose Moog synthesizers and Leslie cabinets were often stacked up to the ceiling.

"It was a really good studio, and the equipment was first-rate," says Offord. "I found the acoustics in the recording room to be a little dead for my liking. I experimented with sheets of plywood and livened it up. It was a comfortable place to work."

The critical response to progressive rock ("We didn't use that term; we called it 'classical rock'") was violent, and by mid-decade punk rockers took direct aim at groups like ELP and Yes. Offord claims that the barbs and brickbats were ignored in the studio. "The bands were very successful, so they didn’t pay attention," he says. "Millions of fans enjoyed the journey of a 20-minute piece of music. The people buying the records weren’t critics anyway."

In the late '70s, Offord relocated to the US, spending considerable time working in Woodstock, New York; Atlanta, Georgia; and Los Angeles. By 1994, however, after completing 311's album Grassroots, he decided he had enough and set about cruising the world in a sailboat with his wife. He considered himself happily retired, but two years ago his son Sam invited him to check out a group called The Midnight Moan. Impressed, Offord remained on dry ground and produced the band's debut album at Pyramid Studios in New York City.

Pyramind could become the new Advision in Offord's life: in recent months, he's been ensconced behind the studio's board producing tracks for singers Sophia Urista and Allie Hill. "I guess I’m back in the game," he says with a chuckle. "I’ve gotten a taste for producing again, although I have to be honest – I do miss my boat.”

On the following pages, Offord looks back at some of the more notable artists from his recording career, including such non-proggers as John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Billy Squier (a collaboration that yielded the most-sampled track in music history) and rock-rappers 311.

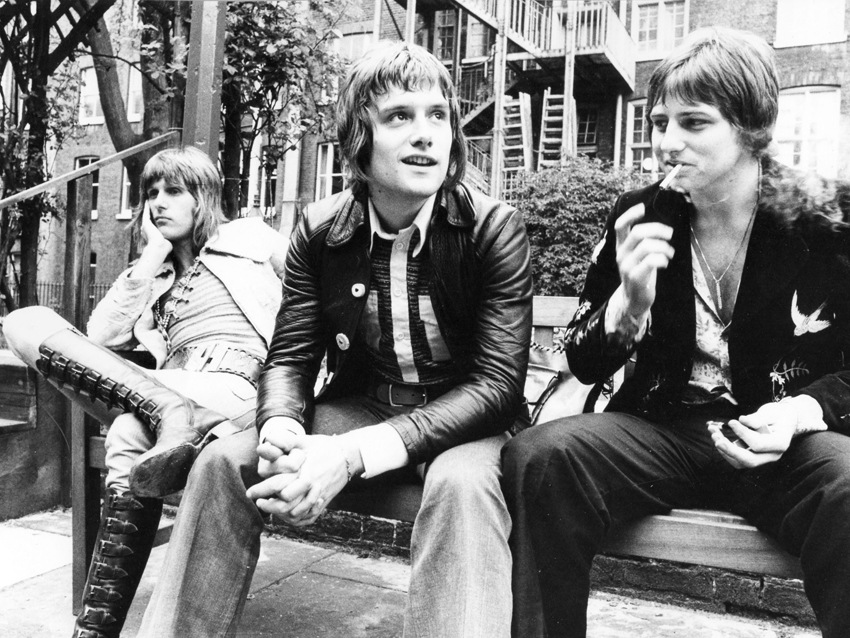

Emerson, Lake & Palmer

“I had a lot of fun with those guys. They were always up to no good, playing pranks and horsing around. Musically, they fit together very well. They were three dynamic and very different personalities. I don’t remember any tensions between them. Whatever problems they had came later in the decade, after I stopped working with them.

Keith Emerson is probably the most technically brilliant pianist in rock ‘n’ roll. I remember doing a song with him called Jeremy Bender [from Tarkus], and he wanted to get a honky tonk sound. There was a Steinway in Advision, and he triple-tracked his part. I slowed the tape down to get that slightly out-of-tune effect, and when I played everything back, it sounded like one guy playing one piano. That’s how spot-on his playing was – every note synced up.

“His organ sounds – my gosh! He’d come to the studio with three or four Leslies and all kinds of Marshall cabinets. He’d take up one entire wall with all of this stuff. It sounded incredible.

“Right around this time, Robert Moog invented the synthesizer. We had one of the first models in the studio. There was a lot of patching involved. At first, I was in charge of programming sounds for Keith. He’d be like, ‘Oh, that sounds good… Oh, I like that.’ Eventually, he perfected it himself and became a real wiz. The first synths weren’t polyphonic; you could only play one note at a time on them. So if you wanted a horn section, you could take up six or eight tracks to get it sounding big. That would be very time-consuming.

“Concepts and structured songs were a little more formed before they got in the studio; they were more together with material than Yes. There was a lot of experimentation with ELP. Songs could change quite a bit sometimes.

“On Tarkus is a song called Are You Ready, Eddy? Normally, before every take, Greg Lake would ask, ‘Are you ready, Eddy?’ And I would say, ‘Yeah, we're rolling.’ What I didn’t know was, they had secretly rehearsed this song, and they went straight into it, just as a joke. Later, they decided to put it on the record.

“There was a very old cockney woman who worked for Advision Studios; she would make sandwiches for us. The band loved to ask her what there was to eat. Her reply was always the same: ‘We've only got 'am or cheese.’ We recorded her and put her on the end of the track.”

Albums engineered are Emerson, Lake & Palmer (1970), Tarkus (1971), Pictures At An Exhibition (1971) and Trilogy (1972).

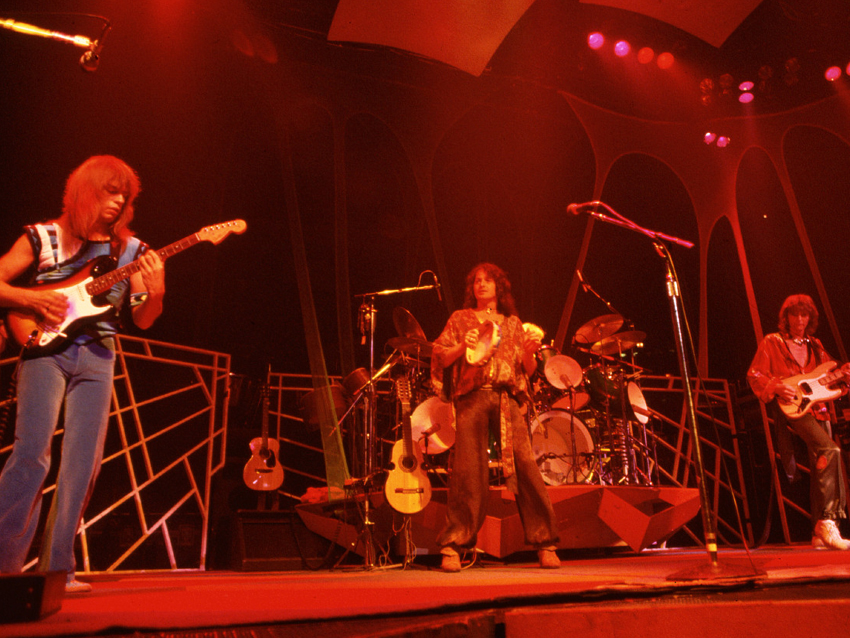

Yes

“We kind of became a family, and I was almost a sixth member of the band. They were brilliant musicians, but there were never any egos. Nobody was trying to upstage the other person or be a show-off. It was all about the song and the album.

“The band would come in with ideas and bits, but songs were really developed in the studio. After we were done with an album, they’d have to learn everything so they could play it all live. There was lots of experimentation – and editing.

“I worked with both drummers – first Bill Bruford and then Alan White. Bill was a very white drummer, in my opinion. He’s brilliant, but there is a certain feel that I wanted to get. Alan is a very soulful player. He’s slightly back on the beat, but it’s done in the right way. It was tough for him at first to play Yes music because of all the time signatures. It wasn’t until the second tour that he started to gel. When he got it, he was fantastic. He played the hell out of Starship Trooper.

“Jon Anderson wasn’t a great musician, but he would come up with songs, and the band would take them and add their bits to them. He had a very cinematic mind. He would say things like, ‘I hear bombs dropping’ or ‘I hear a waterfall.’ That’s how he would describe musical ideas.

“Bill Bruford didn’t like Jon messing with the tracks once they were recorded. I remember we were trying something – Jon wanted to have some echo in the background – and Bill got up and yelled, ‘Why don’t you put the whole fucking record in the background with echo then?’ But what I learned about working with them was, if somebody has an idea, it’s better to try it than to sit around debating it.

“We did some long songs, but they were great. I never felt that anything was too long. If a 20-minute song holds your interest, then it works. I’ve heard three-minute songs that are boring.”

Offord engineered 1970's Time And A Word. As co-producer and engineer, his credits are The Yes Album (1971), Fragile (1971), Close To The Edge (1972), Yessongs (1973), Tales From Topographic Oceans (1973), Relayer (1974) and Union (1991). He co-produced 1980's Drama.

John Lennon/Yoko Ono

“I only worked with John once, on the Imagine album. He had an estate outside of London, like a manor, with a brand-new recording studio built inside. He asked me to come out and do some work, which I did. I felt bad, though, because I could only do a few tracks with him. I had to tell him that I had a prior commitment to record with Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

“The time I spent with John was great. Phil Spector was never around; he only came into the picture after John took his tracks to New York. Phil put strings and all of that stuff on.

“John was very confident about what he was doing. The Beatles had only been broken up for a little while, but I didn’t get the feeling that he was adrift or insecure to be on his own. He wasn’t very technical; he liked to work fast, only doing a few takes of things. He didn’t do a lot of recording on his own, though – it was more a band thing. Alan White played drums on some of the tracks, and he did a great job.

“I would offer opinions to John if I thought something didn’t sound right and maybe we could get it better. He was cool – there was never any kind of attitude from him. He didn’t act like a star or that he was better than anybody else. I remember him being a fun guy.

“At the same time we were doing this, John encouraged me to work with Yoko, which I did manage to do. I liked Yoko a lot as a person – she was very sharp, very educated – but I thought that what she was doing musically was pretty painful. It was like this primal scream thing. I hated it.”

Offord engineered selected tracks on Lennon's 1971 album, Imagine, and the entirety of Ono's 1971 Fly.

Dixie Dregs

“Yes were having problems reproducing their albums live, so I went on tour with them and helped out with the sound. I had these tape machines with me to cue in pipe organs and things like that. It was a blast. We traveled in private planes and stayed in first-class hotels. It can be hard for bands trying to get their careers off the ground, but once you’ve made it to the top, life can be quite nice.

“During this time, I had built my own console that allowed me to do sound for Yes and record their shows. It was great. I took it to Woodstock and recorded some people there, and eventually I brought it to Atlanta, Georgia. I bought an old movie theatre, one of those places with a stage and a pipe organ, and one of the bands from the area came a-calling. They were the Dixie Dregs.

“I guess they were progressive rock, but they had such a strong country thing going – it was like progressive country rock. Steve Morse has got to be the fastest guitar player in the world. He played so fucking fast, I couldn’t believe it!

“The songs were written before we got to the studio. I didn’t help them shape the tunes in any way; everything was ready to go. Their poor violin player [Mark O’Connor] – he would play something, and to everybody else it sounded fine. Steve Morse could always find pitch problems, though, and he’d insist on doing multiple takes.

“He didn’t spare himself: A lot of time was spent on his guitar solos. He would break things down into two-bar phrases, whereas most solos might be 10 phrases. He’d record one two-bar phrase, and once he was happy with that, he’d move on to the next. I wouldn’t call it spontaneous, but he got what he wanted.”

Offord co-produced (with Steve Morse) 1982's Industry Standard.

Billy Squier

“I was living in Woodstock, doing little bits of recording. My gear was in this barn at Levon Helm’s house. Billy came up and made a record with me there. He sought me out, which was nice of him.

“There were great acoustics in Levon’s barn, perfect for getting huge drum sounds. Billy wanted to explore spaciousness. He was a big Led Zeppelin fan, and I think that came out in his music – the big, in-your-face riffs, along with his style of singing.

“Billy had his songs very worked out. He was fairly easygoing but very focused. I was more of a facilitator, really, but I think that’s what a producer should be. Any time you try to put your own stamp on an artist, you're not really thinking about what the music needs to be. You have to know when to stay out of the way.

“The album wasn't hugely successful at the time of its relief, but it's had an interesting afterlife, as the song The Big Beat is now the most-sampled track in music history. The drum beat and the guitar riff have been used by Jay-Z and many hip-hop artists. That's pretty cool. I never would have predicted something like that happening when we made the album."

Offord co-produced (with Squier) and co-engineered (with Rob Davis) 1980's The Tale Of The Tape.

311

“It’s nice to find artists, develop them, get them out there and watch them become successful. I was living in California, and I used to get tapes in the mail from bands looking to make it in the business. One of these tapes came from Omaha, Nebraska, and it was by this band called 311.

“I can’t say I was a fan of rap, but I had kids, so I did hear it and knew what was going on. What I liked about 311 was how they would change from rock to rap to reggae. There was no plan to what they were doing, but I thought they sounded refreshing. I liked the surprises they threw at me. If it was all rap, I probably would’ve gotten bored, but they never stayed in one place for very long.

“I found the band a house in Los Angeles, and I set up an amazing studio in the living room. We were using ADATS – that was the cutting-edge technology at the time. It was a fun atmosphere; we tried things until we were happy. On the first record, we cut everything in the living room except for the drums, which we did in a regular studio. The band didn’t have a record deal at the time, so I was working on spec. After a couple of months, I was able to get them signed to Capricorn Records.

“Having the studio in the living room was great because it cut down on anxiety. No matter who you are, whether you're Rod Stewart or a guy making his first album, if you’re working in a big commercial place, you’re thinking about time and money, and everybody is looking at you – it’s nerve-racking. With 311, I’d be working with the guitar player in the living room, and I could tell him, ‘Look, it’s cool. Whenever you have a solo you like, just press record.’ It was a nice, easy way to get things done.

“I don’t know if ‘progressive’ is the right word for 311, but they did mix up genres. It was interesting. I went on the road with them after the record came out, doing sound for them in empty clubs. That was a long way from the high life with Yes.”

Offord produced and engineered 1993's album, Music, and co-produced (with 311) and co-produced (with 311) and co-engineered (with 311 and Scott Ralston) 1994's Grassroots.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.