Production legend Trevor Rabin on 13 career-defining recordings

When Trevor Rabin showed up at Steven Seagal's house in the mid-'90s to give the action star a guitar lesson, he had no idea that the encounter would lead to a whole new career path. But after the former Yes guitarist (he had left the band following the wrap of their Talk tour) finished teaching Seagal how to play Red House, the actor asked Rabin if there was anything he could do for him in return.

"As it so happened, I told Steven that I was looking to get into film scoring, and I asked him if he knew any agents I could talk to," Rabin says. "Then Steven said, ‘Well, I’ve just finished a movie. Do you want to do it?’ It was all so straightforward. I was familiar with McIntosh, having done the first non-linear album with Talk, and I knew how to orchestrate, so I figured I’d have a go at it. I just jumped in the deep end and went at it."

The music end of film scoring proved to be a cinch for Rabin – in addition to writing and recording with Yes, he had produced bands and worked as a session guitarist both in London and his native South Africa – but there were some elements of film production he had to bone up on fast. "Seagal's film Glimmer Man had all of these Russian agents in it," Rabin recalls. "There was this one character named ‘POV’ – I kept seeing his name in the script, but he never spoke. There would only be a description of where you were. I later found out that POV is a camera direction for Point Of View. I was too embarrassed to ask at first. That's what happens when you kind of bullshit my way in.”

Regardless of how he bluffed his way into the business, over the years Rabin has proved himself to be one of Hollywood's first-call film composers. Since 1996, he's scored 40 movies, 13 of which were produced by blockbuster-meister Jerry Bruckheimer. "I've always done Jerry's films when he's called me," Rabin says. "I know they're going to be exciting pictures and big hits, and they're a lot of fun to do. But I don't want to do only blockbusters and action films. A while back, I told my agent, 'I'd love to do a comedy or a war movie. Or how about a western?' And thankfully, all of those opportunities came along. I've been quite fortunate."

Up next for Rabin are the scores for Boaz Yakin's family adventure film Max and the Syfy TV series 12 Monkeys, and if all goes right, the guitarist is looking to issue a new solo album by year's end. “I got my jazz album out of my blood, so it’s time to do a rock album with vocals again," he says with a laugh. "I’m about a third of the way in on the record, and I really want to finish it. Every time I think I can get back to it, a film comes up and I can’t say no." He pauses, then adds, "It’s a good problem to have.”

On the following pages, Rabin looks back on 13 career-defining recordings.

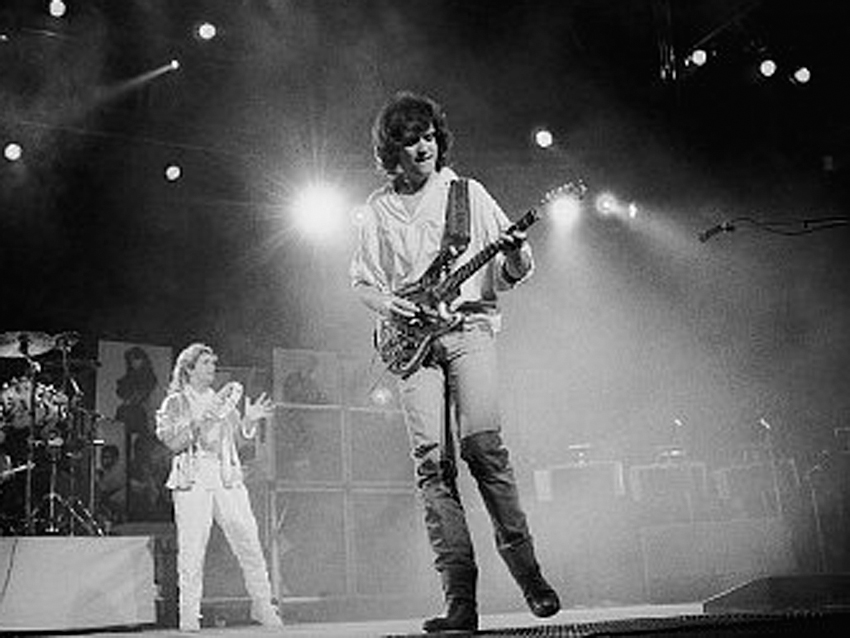

Rabbitt - Boys Will Be Boys (1975)

“That band was so tight, a really great live group. This album was done in one week – recording, mixing, everything. We worked really quickly and efficiently. There were a couple of overdubs that I did, but it wasn’t an elaborate affair. The vibe was definitely that of a band playing live in the studio, with a few embellishments where needed.

“I was already pretty confident in the studio because I’d been doing sessions and production work. I even had a few number one records as a producer, so the whole process of recording and being in a studio environment wasn’t new to me.

“I thought Rabbitt was very strong and that we might happen. Beyond that, there was no real plan to what I was doing. That’s been my whole life, really: You do your best, hope something succeeds and you take it from there.”

Trevor Rabin - Travor Rabin (1978)

“I recorded most of the album before I left South Africa for London. I left Rabbitt because of business issues – we were being ripped off royally. I didn't know what was happening for a while – the band was doing so well and there was money coming in. Put it this way: You’re not ripped off till you’re told you’ve got nothing. Luckily, my dad warned me what was happening, and I got out.

“Every 10 years or so, I’ll come across this album and listen to it, and I’ll go, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I made this so long ago. It actually sounds quite fresh.’ I think the only thing I listen to with a bit of a cringe-factor is my second solo album. The lyrics make me wince a bit. But I enjoyed making this record, and as I said, it sounds good to me every time I hear it.”

Yes - 90125 (1983)

“I was living in London at the time. I had started my own label, made a few mistakes, but was I managing to make a touch of money. Then Geffen came calling. They signed me and wanted me to come to America as a writer. The idea was to surround me with a bunch of big stars, but I wasn’t so sure about that. If they’re big stars but the wrong people, that could wind up being crap.

“Needless to say, we parted company, but before we did I wrote what is basically 90125 – long before I met the band. I went round with that material, and by the way, Clive Davis turned it down. He said it was way too left-field and would never happen. But Ron Fair, who was a small A&R guy at RCA at the time, latched on to the material and tried hard to sign me. He didn’t have the clout then to get me the kind of deal I needed, but he really believed in the material. Long before anyone else, he saw the potential in what I was doing.

“Then I heard from Phil Carson at Atlantic. He wanted me to meet up with Chris Squire and Alan White, who were looking for a band. If that weren’t an option, Keith Emerson and Jack Bruce were looking for a band – Phil knew I’d worked with Jack. As it turned out, I met with Chris and Alan, and that was it.

“I knew what it should be and how it should sound. What’s on the demos is exactly what’s on the masters, although I had recorded the demos in a fairly cheap way. We didn’t have samplers in those days, but I wanted that sampler sound, so I would record a record, and with a delay unit I put that sound in place. That’s how Owner Of A Lonely Heart took shape.

“It’s funny about that song: Lots of people think I did a demo, and then we went in with the band and it completely changed. To be honest, it was done exactly as I had intended. In fact, at one point, Jon Anderson walked up to Trevor Horn and said, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing here or what you’re being paid for. You haven’t added anything to Owner of A Lonely Heart.’ Trevor actually thanked him and said, ‘It doesn’t need any help.’ That was very nice of him.”

Yes - Talk (1994)

“I found this to be a happy experience. When Jon Anderson left to do his solo album after Big Generator, I thought, ‘Great. I’m going to do a solo album, too.’ I took it all in a kind of happy-go-lucky way, really. Jon was doing an Anderson-Bruford-Wakeman-Howe album, and I got a call from Clive Davis and then one from Jon. Both guys told me there was no single – did I have anything?

“I did have some songs, but I didn’t know if I wanted to let them go. I sent them to Clive, and he said they were perfect. But I wasn’t sure about them going to Anderson-Bruford-Wakeman-Howe. So the weird thing was, those songs became the Union album – they were the first three singles. I did them basically in my studio; Jon and Chris came in to sing on them. The album was a bit of a mish-mash.

“I didn’t think that far ahead whether Talk would be my last album with Yes, but I knew I wanted to do a non-linear record. The technology wasn’t really ready, so in order to have 16 tracks of non-linear digital audio, I had to do it with four McIntoshes working together. It was a bit of a technical nightmare, but I managed to do what is done now fairly easily.

“Chris was dead against me working this way. He’d say, ‘Oh, God, what does this have to do with playing?’ I said, ‘It’s not about playing. It’s about playing properly and knowing it’s right, and then taking what you have and working it into this new format.’ Jon was totally into it. He and I worked very well together on it.”

Con Air (1997)

“Simon West, the director, was a delightful guy, but very early on I realized that all the decisions were made by Jerry Bruckheimer. He called the shots. This was my second movie – the first was Glimmer Man – so I was still pretty green in many ways.

“Because I was so inexperienced, there were sort of no rules for me. My idea for was to do a kind of rock ‘n’ roll score with orchestra and weird sounds. Jerry was totally into that, so it wound up being quite easy. It was a lot of work, though. Actually, I’d never worked so hard in my life.”

Armageddon (1998)

“This was my first time working with Michael Bay. Jerry Bruckheimer said to me, ‘You did a great job on Con Air, so I want you for Armageddon. But it’s such a big project and the budget’s so huge, so I’m a little nervous.’ My agent at the time, Lyn Benjamin, said to me, ‘Why don’t you write them a theme? Give them something they can’t refuse.’

“Naively, I thought, ‘All right, I’ll do that.’ [Laughs] Luckily, I nailed it. Jerry loved what I did, but he did say to me, ‘OK, I want you to do this, but we’re gonna have to work you in with some other players.’ I told him, ‘That theme is Snow White. The other Seven Dwarfs are working with me. You can’t have one without the other.’ I was being a bit bold. And he said, ‘All right, that’s fine. If you think you can handle it, go ahead.’ So that’s how I ended up getting the movie.”

Remember The Titans (2000)

“Boaz Yakin, the director, was absolutely phenomenal. I was right in the middle of doing Gone In 60 Seconds. I was working in two studios – one in my home, where I do most of my work, and the other studio is in Santa Monica. Next door to me in the Santa Monica studio was the editorial room for Titans. I knew they were looking for a composer, but I was working really hard on 60 Seconds.

“Boaz came in to talk to me, and we became quite friendly. He said to me that he didn’t know who he should get to do the music. I had a few ideas, some friends I knew. I got one of them to send in a demo, but Boaz didn’t think it was right. Finally, he said, ‘Oh, fuck it. Can’t you do it?’ I told him Imy situation, that I was in the middle of Gone In 60 Seconds, but after speaking to Jerry Bruckheimer, I said to Boaz, ‘OK, I can do it, but you’re gonna have to be patient.’ It ended up with me working 24/7.

“Boaz was very different from Simon West. He had very definite ideas for the music he wanted for the film. The whole thing was a bit of whiplash, pardon the pun. I was doing 60 Seconds, and I had to go into Titans and put a lot of heart and feeling into it. I wrote something for it, and Boaz said, ‘It’s not emotional enough.’ And here I thought it was one of the best pieces I’d ever written. But from working with Yes, I’d learned the art of compromise. With film, you’re collaborating with a director or a producer, so it’s a bit like being in a band in that way.”

National Treasure (2004)

“This was a great experience, although Jon Turteltaub, the director, was a bit impossible – charmingly impossible, I should say. He’d come in and listen to a seven-minute piece of music, and he’d say, ‘That’s fantastic! It’s done.’ He’d rave about it and then say, ‘OK, let’s listen to it again and I’ll make some notes’ – by the time he was done, the notes were 30 pages long. A week later, half of the notes would go away without me changing anything.

“What was funny about this one was, I’d written the main theme and played it for Jon, and he said, ‘It sounds like a cowboy theme.’ So I told him, ‘Have a listen to Star Wars. If you put that music against a western, it’d be perfect.’ I didn’t really see what Jon was saying as a negative – one could be used for the other. Luckily, Jerry was there, and he said, ‘No, I love it,’ and it stuck. Otherwise, Jon would’ve gotten rid of it."

Dominion: Prequel To The Exorcist (2005)

“This was a bit of a strange experience. I never met the original director, Paul Schrader. All I knew is that a first version of the film was done and they didn’t like it, so they decided to do a new version from scratch. Renny Harlin called me and asked if I’d do it – I had done Deep Blue Sea with him – so I said, ‘Sure, happy to help.’

“When I finished Renny’s version of the movie, the film company decided to put it out, but they also decided to put the other version out, too, the movie they had shelved. They figured it was done and it wouldn’t cost them anything, so why not?

“There was another composer, whom I’d never met [Angelo Badalamenti], and my score was kind of stuffed in with his. I was credited as having done the music with him, but we’d never met. I never met Paul Schrader, either. The whole thing was a bit weird.”

The Great Raid (2005)

“John Dahl was absolutely great to work with. He was very encouraging but a little hands-off, which is fine. He pretty much let me go. The one thing he did say to me was, ‘For the most part, I want this to be done as an orchestral score.’ He didn’t want any MIDI or anything like that.

“These days, with orchestral scores, you do short strings first and then the long strings, and then you do what we call the ‘remote-control virus.’ It’s never about writing for an orchestra and letting the musicians perform. And on this project, that’s what we did. We went to London and the orchestra played. That was it – that was the score.

“It was just so rewarding. With Jerry, it would always be ‘Make sure the brass is separate in case I want to get rid of them or turn them down.’ When you do the thing all at once, that's not an option – it's all one piece of music. Jon really wanted that sound, but I did tell him, ‘Just make sure, because if we do it, that’s it. It is what it is.’ It took a little longer to do because it was all about the performance. No editing.”

Flyboys (2007)

“Tony Bill is a fantastic director and such a great guy. Once again, this is a score that we did all at once in London. Any MIDI that was attached was added at the end, just to do a bit of this or that. It was a purely orchestral score all along – that was always the idea.

“Tony was very generous with me. I would play him a theme on the piano, and he would say, ‘I like the idea, but keep in mind the subtext of what the character is thinking and saying. There should be a yearning that’s underneath it all.’ Now, that sounds a little ‘Oh, come on. Speak English, you know?’ [Laughs] But he’s so poignant and on the money, and everything he said was so relevant and made such sense. It really made a difference in the sensitivity of how I went about my job.”

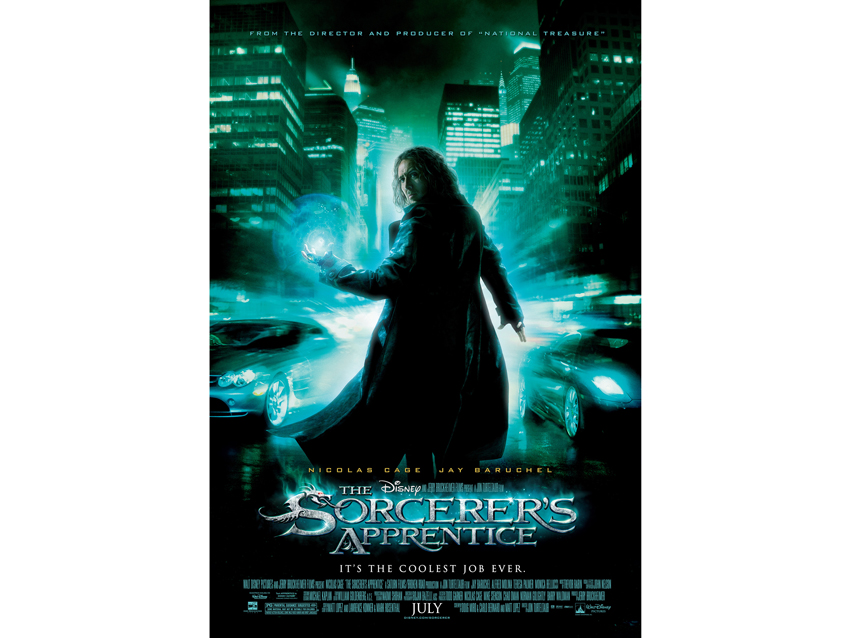

The Sorcerer's Apprentice (2010)

“Another Jon Turteltaub film. He was charmingly impossible, as always. The problem with this film was, they didn’t know how to end it. They had a number of endings that they weren’t happy with, so then it was like, ‘Let’s throw some money at CGI for the end.’ I don’t think they knew how to resolve the film, which made things a little difficult in terms of the music – things kept changing all the time.

“This is something I’ve learned as I’ve gone along. For the first couple of movies, I would do my thing, and if the director said, ‘I don’t know about this,’ I would fix it immediately. Now I don’t touch anything, because A) it’s likely to change, and B) that same theme might work somewhere else in a different environment. So I leave problem areas till later.

“The other thing is, I did something called the ‘underture.’ What that means is, I’d play the movie without any sound or just a bit of dialogue to get a feel for it, and I’d start writing, just putting ideas and themes together. Once I got some ideas – this theme here, a theme for these people – I found a way to organize them together. After that, I did a fully blown orchestra version of it and sent it in. ‘Here’s the idea I have for the movie.’ If they liked the themes, it made it easy to write to picture, because they recognized certain parts. I’ve done that on everything since Deep Blue Sea.”

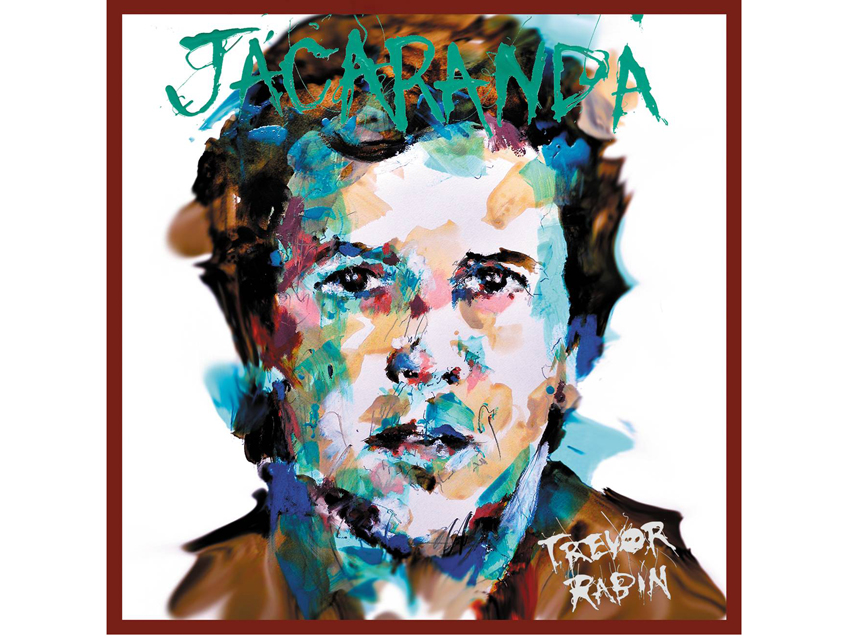

Trevor Rabin - Jacaranda (2012)

“Film scoring probably changed my approach to recording in some ways, but what it really did was afford me the financial freedom to do whatever I wanted without worrying about how it was going to do. And that’s what I did – whatever I wanted.

“Even as a player in Yes, I could never do what really pushed me. This album did push me from a technical standpoint and playing-wise. This was helped a lot by guys like Vinnie Colaiuta. Working with him was like working with someone who’s not completely human. He was just ridiculous. What a drummer! He was a real pleasure to work with.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.