Tom Werman

In describing the timeline of his professional life, producer Tom Werman puts a spin on the popular Hollywood proverb that there are five stages to an actor's career: "Who's Tom Werman? Get me Tom Werman. Get me a Tom Werman type. Get me a young Tom Werman. Who's Tom Werman?"

He laughs easily, then adds, "I'm OK with that. Listen, I got to be a successful record producer in the '70s and '80s. That's the best job you could have had during that time. The budgets were big, the records sold like crazy, and the perks were incredible. I had a lot of fun and lived the kind of life most people dream about. I used my CBS Records American Express card like you wouldn't believe.”

Starting out as an A&R man for Epic Records in the early '70s, Werman quickly distinguished himself as having an ear for rock radio, signing REO Speedwagon, Cheap Trick, Ted Nugent, Molly Hatchet and Boston, among others. Becoming a producer wasn't necessarily in his game plan ("I didn't have a plan"), but because of the way Nugent's deal was structured, giving the guitarist's manager production responsibilities, Werman ensconsed himself in the studio to protect his investment. "I wound up doing so much that the manager gave me production credit," he explains. "Suddenly, I was a producer."

Werman admits that he didn't set out to specialize in hard rock, but that once he got rolling, "people assumed that's what I did," he says. "They like to pigeonhole you in this business. Ted Nugent was hard rock, and hard rock was what I was offered to produce. Truth is, my ears and my instincts are pop, and that’s why my bands got on the radio – I went for hit singles.”

At his peak, Werman's efforts ruled the airwaves, turning many of his signings into stars. Over the course of his career, the producer racked up an astounding 23 gold, platinum and multi-platinum releases. "But I was doing what came naturally," he stresses. "I listened to pop and rock radio since I was nine, so that’s what I wanted to hear from my bands. I didn’t make records for other people; I made records for me.”

And when it was time to get out, Werman did so with no regrets. "I read a book called Who Moved My Cheese?" he says. "It’s a self-help book about moving on to the next phase of your life. It made a lot of sense to me, and two weeks after reading it, I bought a bed and breakfast in Connecticut. My wife and I moved in, set up a new business, and we've been at it ever since."

Asked to name what he misses most about his high-flying times in the record business, Werman chuckles and says, "Nothing. I did it, and now it's over. I made something like 50 records, many of them big, big sellers. I spent my life in windowless rooms, with tobacco and alcohol and recreational drugs. Somehow, I was sane and smart enough to know when enough was enough. Most people should be so lucky."

On the following pages, Tom Werman talks us through the most important and memorable records of his career.

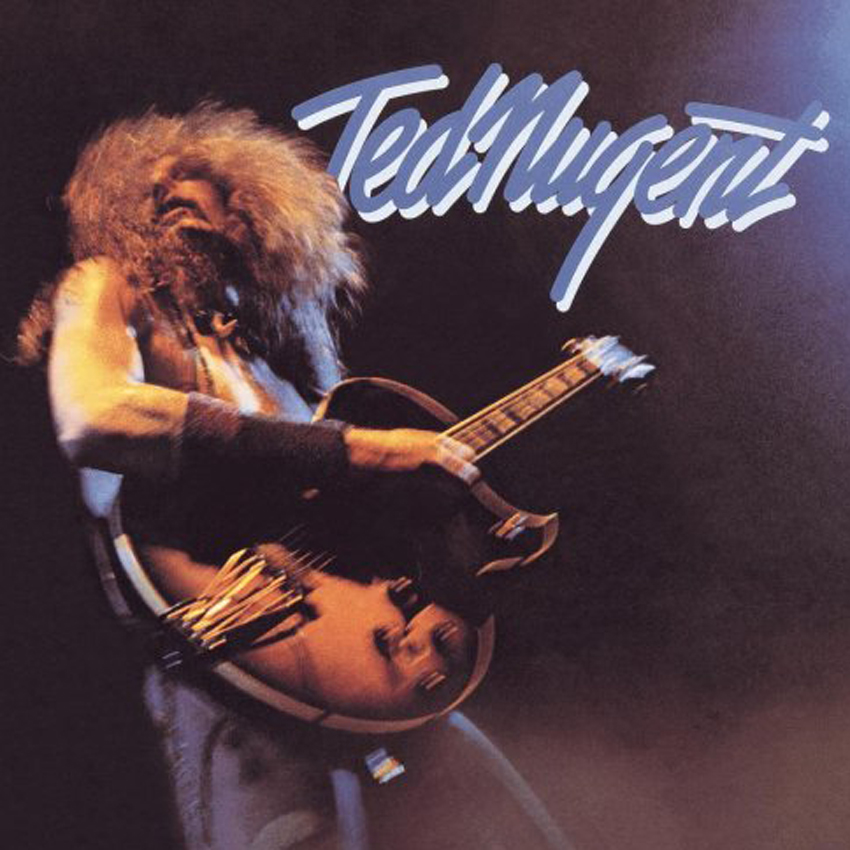

Ted Nugent - Ted Nugent (1975)

“Even on this, his first album, Ted was a total pro in the studio. He was extremely focused, fairly dictatorial and knew every part he was going to play. I served as quality control. I didn’t have much to do with the structure of the songs, the length of the songs, the solos, what he played – I just told him when he had to fix something.

“I learned so much making the record. I learned how you start with the drums, do the bass, get the guitars – the layering. Despite what people might think, very few records are made truly live, and there’s a reason for that: they sound terrible.

“We finished the album, and Lew, Ted’s manager at the time, decided to mix it on his own. It wasn’t great, so I asked my boss to give me $5,000 dollars to go and remix it. I had never mixed a record before, but I had a blast – and made the kind of album I wanted to hear. On Stranglehold, I used delays to create this really wild guitar duet with Ted – it was like two guys were playing.

“I sent it off to Ted for his approval. He called me up and said, ‘I love what you did with Stranglehold – but don’t ever do that again without asking me.’”

Mother's Finest - Another Mother Further (1977)

“Nobody mentioned the band to me, nobody was even talking about them. I went to see them play in Atlanta, and they were ferocious on stage, truly phenomenal. I signed them and got them into the studio.

“A mostly black rock ‘n’ roll band with two white guys – people didn’t know what to think of them. They were tight, rocked hard, and man, did they love Led Zeppelin, which is what they sounded like – a very funky version of Zeppelin.

“I tried to bring a commercial sensibility to them, a pop side to go with their funk and hard rock. But the record stiffed. Radio just didn’t take to it. The official line I was given from the label was, ‘It slipped through the cracks,” which meant it was too white for black radio and too black for white radio.

“Even so, I think they were ahead of their time. I’m very proud of this album.”

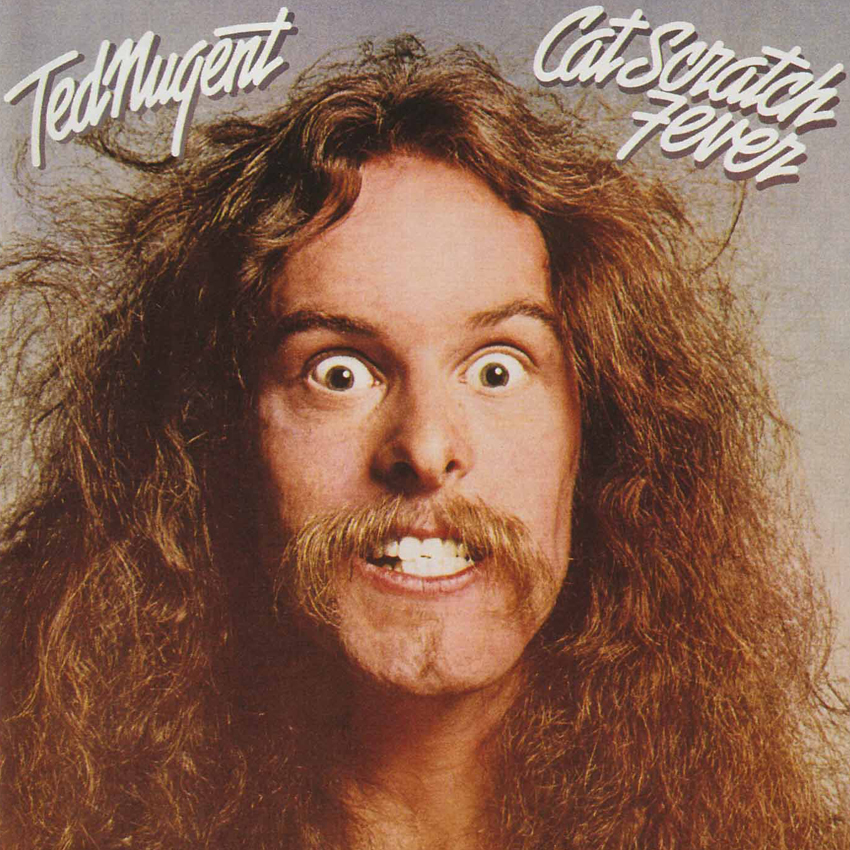

Ted Nugent - Cat Scratch Fever (1977)

“With the song Cat Scratch Fever, Ted finally wrote a real single – a hit single. This was the linchpin for his whole career, because even though he was already successful, now he was on the radio.

“There was one lyric we had to change on the title track. Originally, Ted sang ‘I got it from some pussy next door.’ We had to change ‘pussy’ to ‘kitty.’ I think everybody knew what he really meant.

“We had a lot of fun making this record. Ted was the same way he always was: focused, determined, prepared, funny, serious, totally consistent. Because he didn't do drugs or drink, you never had to worry about what kind of Ted you would get. I've never seen him altered in the slightest.

“As a guitar player, Ted knew what he was doing for the kind of music he made. He wrote solos and committed them to memory. Very rarely would we vary something in the studio. Making records with him was a breeze.”

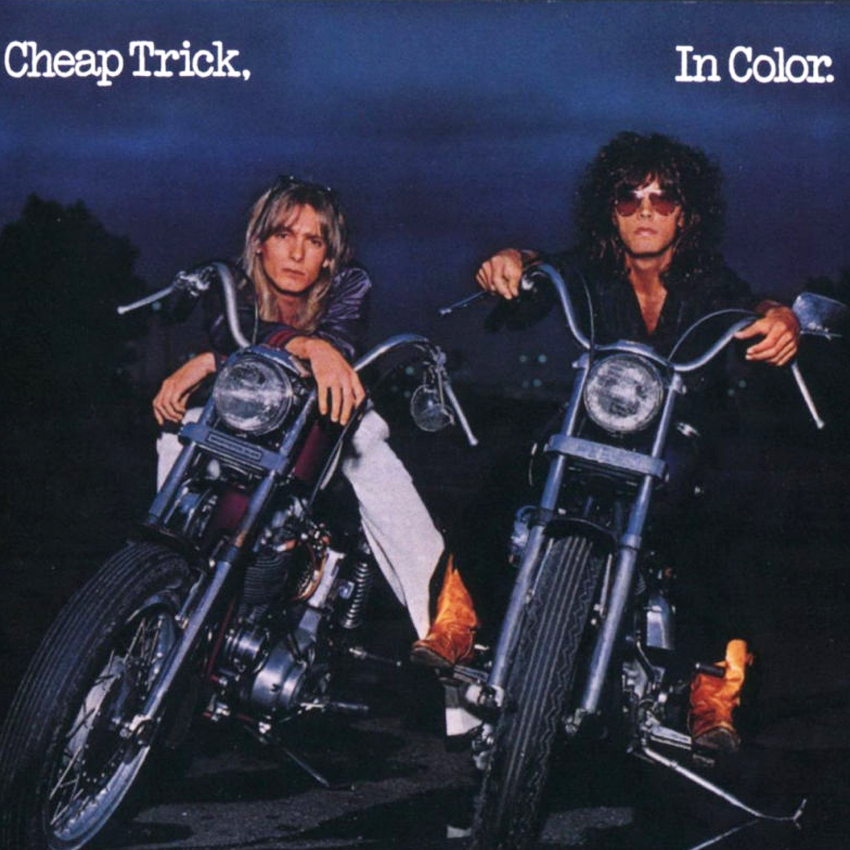

Cheap Trick - In Color (1977)

“This is the first record I made with Cheap Trick, and it’s the first record I ever did in LA. The band asked me to produce them when Jack Douglas, who did their first album, was unavailable – he was busy with Aerosmith.

“Even though I was in a studio I had never been in and was working with a brand-new engineer, this record came together really quickly. Cheap Trick were great to work with, a lot of fun.

“I Want You To Want Me was a fabulous dancehall type of song, and a perfect pop tune, and it was meant to be a little campy. I put the piano on – a guy named Jai Winding played it. I remember asking the band what they thought of it, and Rick Nielsen kind of shrugged and said, ‘You’re the producer.’

“The band never had any confusion in the studio. Rick wasn’t like Ted Nugent in that everything was totally worked out and committed to memory. He liked to have an idea for his solos going in, and then he’d polish them while we were tracking.”

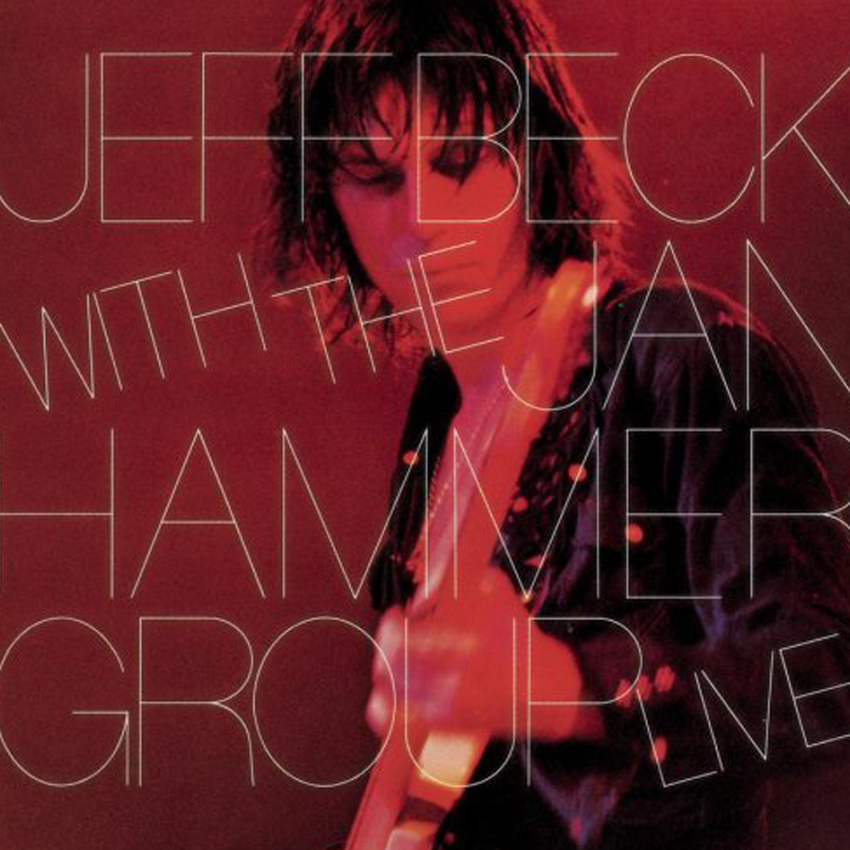

Jeff Beck - Jeff Beck With The Jan Hammer Group Live (1977)

“I went on the road with Jeff when Jan Hammer, the keyboardist, was in the group. Jeff is a true genius, one of the greatest guitar players ever, but he rarely mounts a tour on his own – he’s always playing with somebody as a featured star. On this tour, Jan assumed something of the boss role.

“I supervised all of the recording. I remember half of the album was from a gig in Reading, Pennsylvania, at a converted porn movie house. After we had all of the recordings, Jeff and I went into Alan Toussaint’s studio in New Orleans, where we prepared something like 64 rough mixes. We compared everything till we found the best ones. They were sounding really good, I must say.

“The night we were finished with the roughs, we went out to dinner – Jeff, Jeff’s manager, Jan and I. During the meal, I brought up the subject of mixing, and as I was about to say where I wanted to do the real mixes, Jan said abruptly, in a voice just like Arnold Schwarzenegger, ‘Either I mix the album, or there will be no album.’ He was dead serious.

“That was that. If you listen to the album and think the keyboards are a bit too loud, or even a lot too loud, that’s the reason – Jan mixed it. It’s a great album nonetheless.”

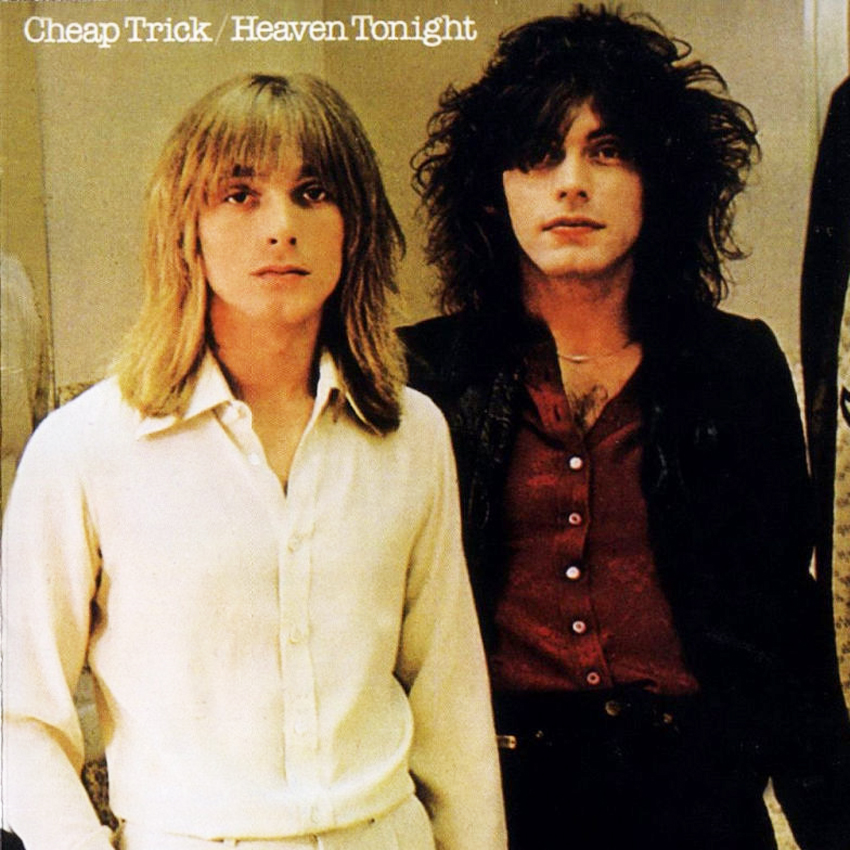

Cheap Trick - Heaven Tonight (1978)

“Now we’re talking about Surrender and On Top Of The World. The band was really hitting their stride. They were bringing a lot to the studio, but I brought stuff as well, like the synthesizer line that I borrowed from The Who’s Baba O’Reilly for Surrender, which really supported the guitar riff.

“The whole record has great material. Listen to the song Auf Wiedersehen – a really fantastic, driving, almost punk song. It was right up there with anything being done at the time, and it still stands up today. There’s a song called On The Radio which has a DJ rap – I wrote that and I’m the DJ doing the talking.

“Most of the songs were finished before they got to the recording stage. I worked them a little bit with Rick; we’d rearrange things here and there. Sometimes we’d take the chorus from one song and put it with the verse from another, and most of the time things worked.

“The guys were brilliant in the studio, absolutely brilliant. Bun E. Carlos would do all of his drum tracks in three days, and then he’d put a sign on his drums that said ‘Gone Fishin’’ and fly home. He’s the best drummer I ever worked with. The same goes for Robin Zander, the best singer I’ve ever produced. The guy’s insanely good, quick and vastly underrated.”

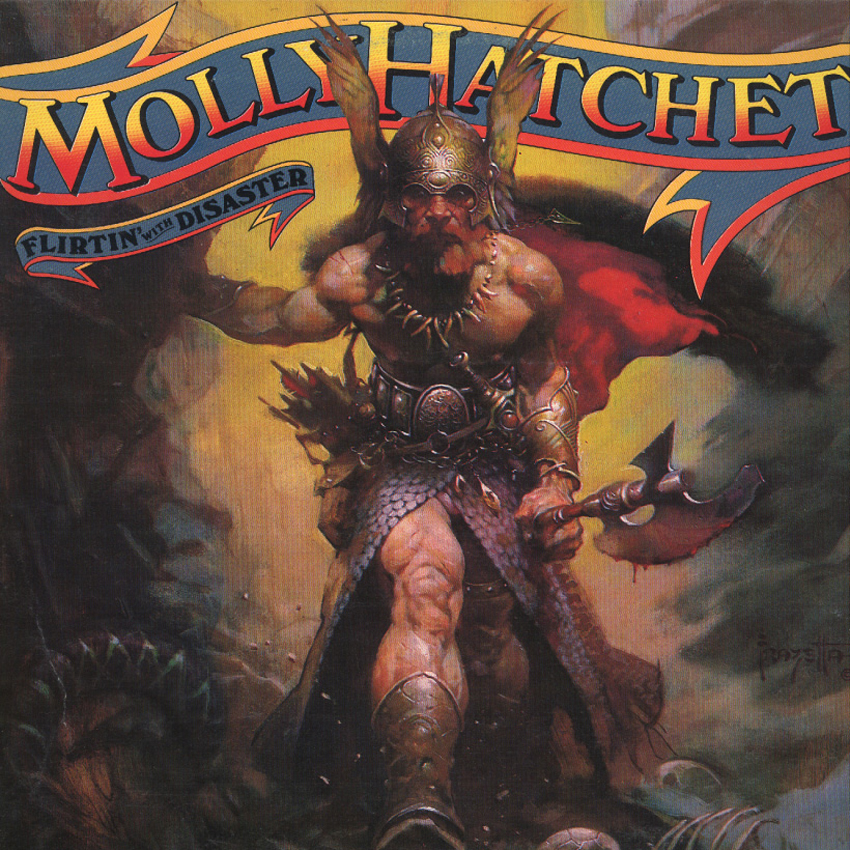

Molly Hatchet - Flirtin' With Disaster (1979)

“They auditioned for me while I was remixing a Cheap Trick single in Atlanta. Talk about blowing me away - I was really impressed with their three-guitar lineup. These guys did that whole Southern rock chops thing so well. They reminded me of Lynyrd Skynyrd, who I tried to sign.

“Danny Joe Brown was a fantastic vocal presence, a big guy with a big voice. And Duane Roland, the second guitarist in the band, had a very unique style, just honey smooth. His solos are so identifiable on the records.

“Without question, Molly Hatchet were the most ‘street’ band I ever signed. They made Motley Crue look like upscale, suburban prep school boys. It’s funny, though: You’d think that these Southern guys who were known for hard living and getting in bar fights and clearing rooms would use big Marshall stacks. Nope. They used Dwarf amps in the studio, these little things. We got a killer sound with them, too.

“The guitar thing was all worked out. They got in the studio and did all of their choreographed parts. It was really something. I didn’t think that the song Flirtin’ With Disaster would get on the radio, but I was thrilled when it did.

“Dave Hlubek was another guitar player in the band, and he was pretty much the leader, too. Right after the audition, when I told the guys they were great and I wanted to sign them, he shook my hand and said, ‘Mr Werman, all I want is my front teeth.’ That’s when I noticed he didn’t have any. From this record, he got his teeth... and a whole lot more.”

Cheap Trick - Dream Police (1979)

"It's probably my best overall production. The synth that I used on Surrender came back on Dream Police, the song. I even sang on it – that’s me going, ‘Police! police!’ in my little falsetto voice. The assistant engineer sang with me, too.

“In Gonna Raise Hell, I put some organ in the middle, which gave the section a real religious, sanctified feeling. I had a lot of fun working with the guys. It felt like a true collaboration between us.

“As always, the band were total pros. The only problem with this album was that the group had a tour booked and we only had 30 days to do the whole thing. And then after we finished it, it sat on the shelf for eight months because the Budokan live record was selling and the label wanted it to play itself out.

“The breakdown section in Dream Police was all planned out; Rick had the entire thing written. I wish that the drums were louder, though. It’s almost like the Keith Moon drum performance in Won’t Get Fooled Again. Bun E. did a brilliant job, just amazing. Incredible fills. Everything he played should have been louder.”

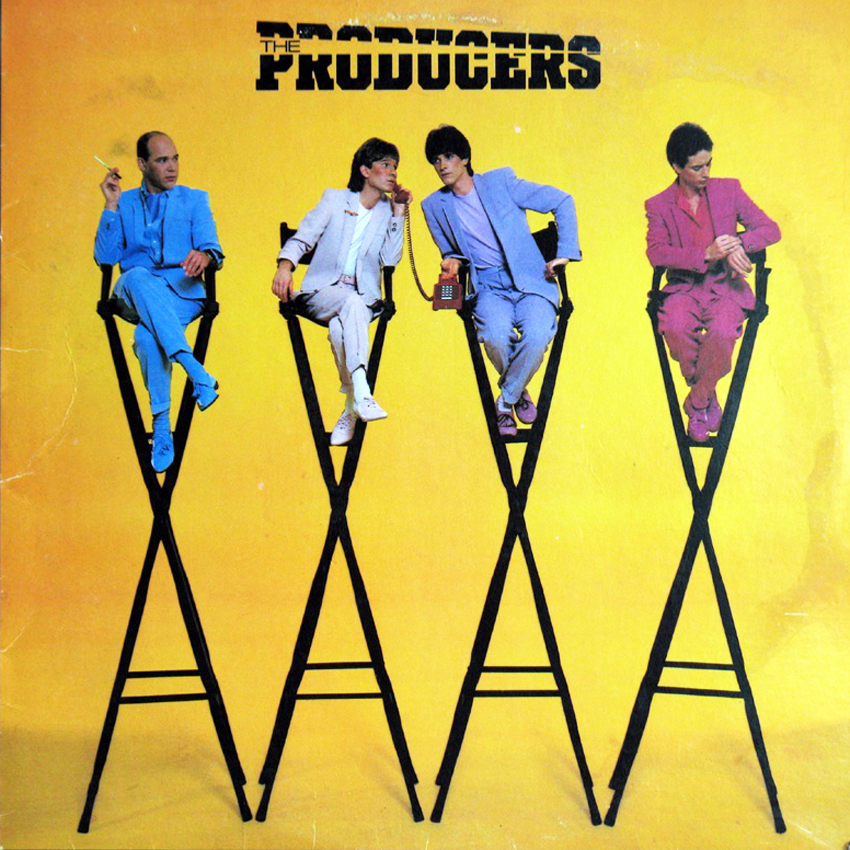

The Producers - The Producers (1981)

“I love this album. The Producers were a fantastic band out of Atlanta that should have been huge. For some reason, they just didn’t pop. It happens – and it always breaks your heart.

“They were brilliant musicians, great people, bright, clever, funny, easy to work with, and they wrote wonderful songs. I can’t say enough about them.

“What’s He Got, A Life Of Crime – these are just phenomenal songs. I tightened them up a bit, but they were pretty good to go. In terms of style, The Producers and Cheap Trick were my meat and potatoes – real power pop.

“What a disappointment that radio didn’t jump on this album. I think a big problem was that it was the first release on Portrait Records, which was a subsidiary of Epic. There were some glitches with the promotion. But people do know about it this album. I get e-mails to this day from fans raving about The Producers. It’s nice to know they're appreciated.”

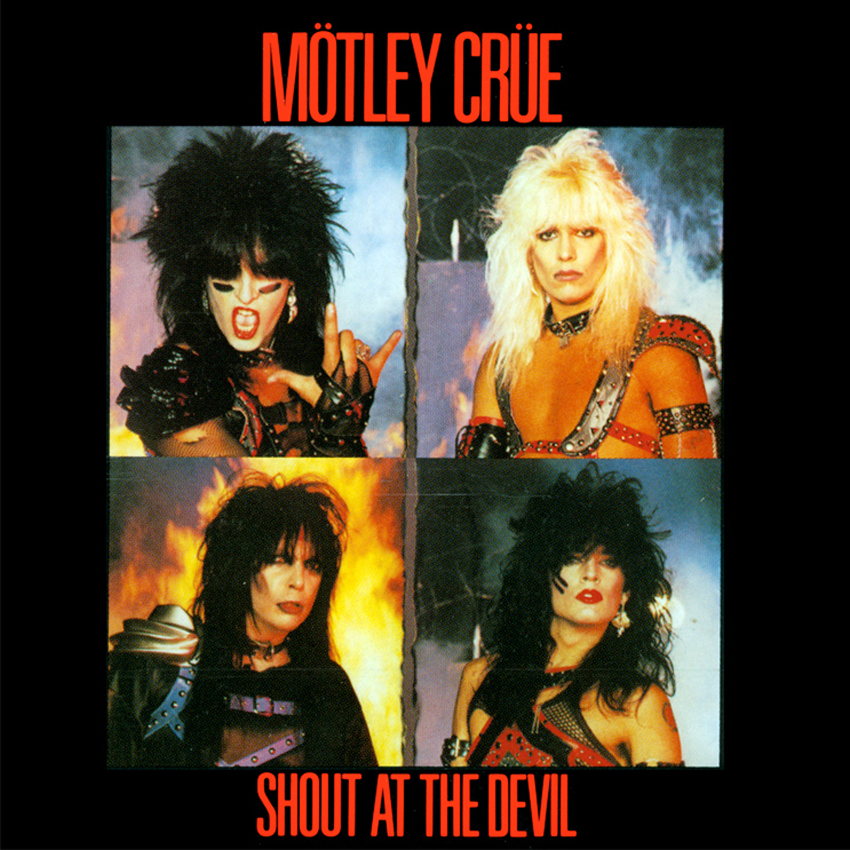

Motley Crue - Shout At The Devil (1983)

“I was told that the band were creating a real scene on the Sunset Strip. I went to see them, and sure enough, there was a big buzz. They had a look, the attitude, the right songs – it was all right there.

“In terms of sound, the album we made was pretty grungy. I much prefer the sound we got on Girls, Girls, Girls, but for what this album was and what the band was doing at the time, it worked.

“This record was another hard one. Nikki Sixx had broken his shoulder when he drove his car off the road, so that affected his bass playing. It took us half a day getting a single bass performance. That's a little long for a bass track.

“Tommy Lee is the second-greatest drummer I’ve ever worked with, with the first being Bun E. Carlos. Tommy was very enthusiastic, creative, energetic and totally into experimenting with sound. He could nail a track fast, too. Mick Mars was solid, a very together guitarist who doesn’t get the recognition he should.”

Twisted Sister - Stay Hungry (1984)

“This was a tough record to make. We spent three days trying to get a rhythm guitar sound for Jay Jay French. It was hell. After that, things got rolling. Dee Snider was very much like Ted Nugent. He didn’t drink or do drugs, and he could be fairly dictatorial. It was his band.

“Dee was a solid writer and something of a stylist. Captain Howdy, Street Justice, The Beast – there was kind of a rock opera vibe to the way everything played out. Dee wrote about himself, his experiences, his life. He had a vision for what he was putting across.

“In a way, the songs were almost nursery rhymes, and that’s not a put-down - that’s just the way Dee wrote. He made sure that everybody could understand his melodies. We’re Not Gonna Take It – it’s like a kids’ song, but it works.

“Twisted Sister were extreme theater. They weren’t the greatest live band around, nor were they the most amazing musicians, but I knew that I could take their schtick and capture it on tape. Again, it was a tough album, but that’s what made its success so sweet.”

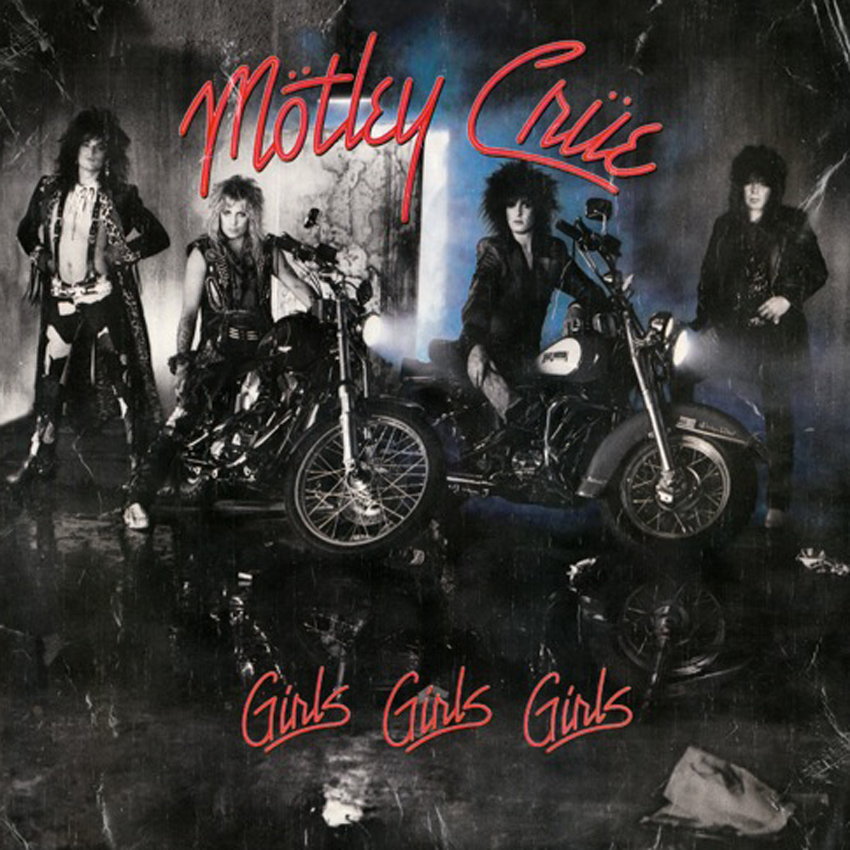

Motley Crue - Girls, Girls, Girls (1987)

“We had made Theater Of Pain, and that was a struggle. The band was experimenting with some hard drugs during that record, and that’s not good for playing, decision making or anything else. By the time we got to Girls, Girls, Girls, they had straightened out and were much stronger.

“We got a great guitar sound. This is the kind of rock ‘n’ roll record that is right up my alley. Things were tight and punchy – it was powerful.

“The song Girls, Girls, Girls was really, really good. The minute I heard it, I knew it would be a hit single. And the guys did their research lyrically. Name-checking various strip clubs… they knew their subject matter well.

“The motorcycles you hear in the song? That’s me. I revved up Vince Neil’s Harley at the beginning, and for the end I’m riding off on Nikki’s. We used stereo mics with a Nagra reel-to-reel and recorded the bikes right outside the studio.

“Mick’s rhythm guitar playing is a real key to this band. On the song Girls, Girls, Girls, his rhythm guitar is the whole hook. If you look at all of my big hits – this one, Cat Scratch Fever, Surrender – they’re all driven by the rhythm guitar.”

Poison - Open Up And Say... Ahh! (1988)

“A huge seller, probably the biggest I’ve ever had. But it was a challenge: CC DeVille was erratic, and we had to take a lot of time to get his parts on tape. He was into drugs at this time, so he wasn’t in the best shape. He tried hard, though.

“The rest of the band did, too – they were hard workers. They knew they weren’t astounding musicians, but they dedicated themselves to being the best band they could possibly be.

“I’ll never forget the one day that Bret Michaels played me a brand-new he had just written. I gave him my acoustic guitar, and he sat down and sang something called Every Rose Has Its Thorn. It was nothing more than a basic country song, but I knew it was a hit – a big hit.

“The guys were very pleased with the production I put to the song. It was a little sweet, a little ‘power ballad-y’ – there were ‘oohs’ and ‘ahhs,’ strings, some Eagles-type harmonies – but it was just what the song needed. It tugged at your heartstrings. It got the band on practically every radio station around. You can’t beat that.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.