Production legend Phil Ramone on 15 career-defining records

He's produced records for a staggering array of some of the biggest names in music, everyone from Frank Sinatra to Billy Joel to Dionne Warwick to Paul McCartney, spanning every conceivable genre. But despite having his name on hundreds of millions of albums, Phil Ramone's ego is surprisingly intact.

"I like to joke with people, ‘I’m the guy on the back cover,' the affable producer says. "It’s not like in the movies where it says, ‘Steven Spielberg presents Abe Lincoln.’ What I do is kind of invisible.”

Ramone's humility might be traced back to the training he received working as a 15-year-old junior assistant at a New York recording studio. "I was what they call a 'tea boy' in England," he says. "Not the most glamorous job in the world, but the experience I gained was invaluable."

Having earned his gofer stripes, Ramone was promoted to assistant engineer and assigned to cutting demos with hungry, hopeful young songwriters, people like Paul Simon. The Brill Building was a hotbed of creativity, and the budding boardsman quickly learned how to make quick conceptual records that would give artists an idea of how songs should sound. "The trick was to make more than just a piano and voice sketch," Ramone says. "I got my chops that way. I even started to work with echo chambers, which was a very big deal then."

Before long, Ramone gained a reputation as a creative sound technician, and his ability to craft recordings with the city's young rockers, many of whom were close to his own age, grew. "Some of the more ‘experienced’ engineers had problems with rock 'n' roll," he says. "They didn’t want to deal with these heavy-laden guitars and the loudest strums you ever heard. But I loved it, and so that really opened doors for me."

Asked to name his big break, Ramone cites the recording of the 1959 album The Genius Of Ray Charles. The arranger was Quincy Jones, and the team of Tom Dowd and Bill Schwartau were engineering. "I was the assistant on the record," Ramone says. "There were a lot of musicians booked for the session – more than I had ever worked with before. Ray Charles’ piano was pushed right up against the studio glass. But Quincy liked what I did, and that led to my doing other things with him. Pretty soon, I was being talked about in the recording world."

That same year, Ramone launched his own independent studio, A&R Recording, and his career took real flight. Whether engineering or producing, he describes his behind-the-glass philosophy as a mixture of technical know-how and personal instincts. “I respect and know that you need to earn the musicians’ confidence and trust," Ramone says. "We’re there not just to accommodate, but we need to have the artist walk in the room and say, ‘Hey, man, that sounds great.’ I’m very fussy about miking and figuring out what a record needs. The bond between an artist and producer is less about dialogue and more about results."

Ramone credits his ability to seize upon spontaneity as one of his key attributes in the studio, and it's resulted in music that has provided the soundtrack to the lives of millions of listeners. "You have to be able to run as fast as the artist," he stresses. "Capture the magic early on. After a few takes, people start intellectualizing what they’re doing, and it loses something. What’s special happens right away, so you have to be ready for it.”

On the following pages, Ramone takes a look back at some of the more memorable moments of his brilliant record-making (and record-breaking) career.

Wes Montgomery - Movin' Wes (1964)

“People really liked the producer, Creed Taylor, but he was a very shy guy. Sometimes he gave me the responsibility of going into the studio to say what he wanted to say. I learned so much from the experience. When nothing’s working, you have to do whatever you can to make the next hour count.

“When it comes to a great guitar player like Wes Montgomery, you have to say to yourself, I know who I’m sitting with. I know what he can do. That’s really what it’s about.

“We had to work quickly, so again, it’s about getting that magic on tape right away. And if Wes Montgomery is playing his guitar, just being in the room and hearing what he’s doing is 80 percent of the job. The rest is making it sound the way it should.”

Burt Bacharach - Reach Out (1967)

“Burt and I are still friends. We’re still doing stuff together. I love somebody who is so meticulous, but the difference is sometimes how an artist perceives himself. He’s a writer and composer who doesn’t like you to mess with the chords or the rhythms. And with Burt, why would you mess with something that is so personal?

“The standard 4/4 time signature is not part of his makeup, and so the magic of what he and Hal David did, which you can hear it on this record, is how they fit the music into the lyrics or how they refit the lyrics into the music. There’s a lot of understanding at work in the craft.”

Dionne Warwick - In Valley Of The Dolls (1968)

“A very important moment in my adventures with Burt and Hal, and even Dionne. She learned the songs very quickly. There was no formula in the way Burt and Hal wrote, and I must say, every time we did a date, we got very lucky.

“Valley Of The Dolls was a brilliant record, and it was just one of many, many hits she’s had. We did one this year, in fact, a record called Dionne Warwick Now, a 50th anniversary of her show business career. I’m very proud of it.”

Paul & Linda McCartney - Ram (1971)

“Paul had been in New York doing some songs at A&R Studios. He and George Martin had written out a chart for Uncle Albert, and I encouraged Paul to conduct the musicians. ‘You’re nuts, I don’t want to do that,’ he said. But I got him to do it. I told the musicians, who were kind of New York snobs, ‘Listen, Paul is going to conduct, and he’s from England.’ That’s all I told them. I didn't say anything more. Later on, they were in the bathroom, saying things like ‘Was that Paul McCartney… the Beatle?!’

“It was the second album he did after the McCartney album. His child Mary was in the studio a lot. I never had a playpen in the control room before. Paul could pretty much play anything. He’s a terrific piano player, he can play drums, and he’s not the worst bass player in the world. [Laughs]

“He was very confident of what he was doing. There wasn’t any tentativeness to him or anything like that. You couldn’t bullshit him. If something didn’t sound right, you had to express your feelings. You might have been putting your head in the chopping block, but it was better than not speaking up.”

Paul Simon - Paul Simon (1972)

“I only did one song on this record, Me and Julio Down By The Schoolyard. Roy Halee produced the album with Paul. What happened was, I got a call from Paul, who said, ‘Roy is in San Francisco, but I want to try this tune. Can you give me some time in the studio?’

“It was a great meeting between all of us – it was Paul with a four-piece band. It was quite unusual how we miked Paul’s solid-body guitar. I put a mic right up near his strumming hand, like you would with an acoustic. Nobody did that – you were supposed to mic an electric guitar at the amp. But I liked the sound he was getting; it was so percussive. In truth, we never turned the amp on. Paul created his sound with his hand. The whole record is percussion and bass.

“And that sound was the reason why I got to do the next record… ”

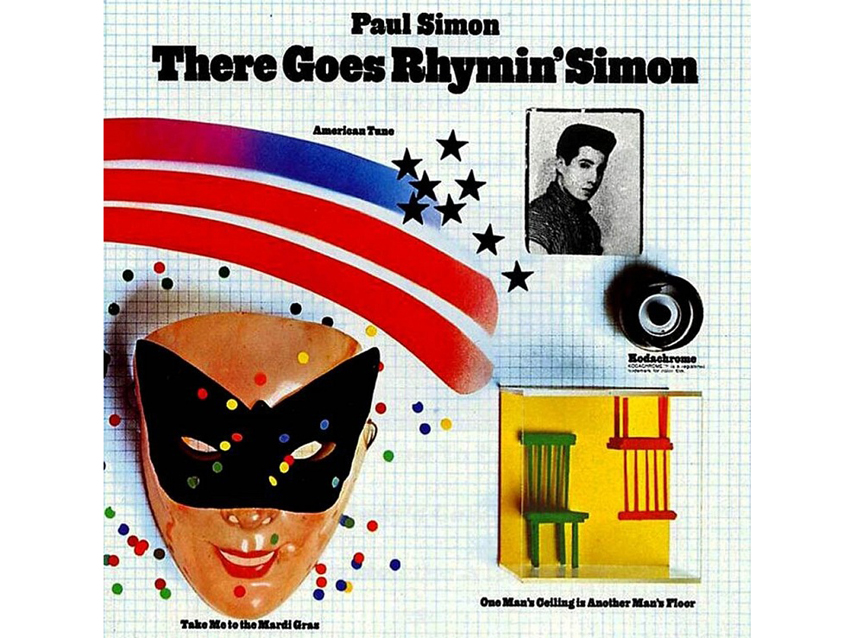

Paul Simon - There Goes Rhymin' Simon (1973)

“This is a collection of amazing people. Paul introduced me to Muscle Shoals, which I’d known about but had never been there. Eventually, it became a stop for me on a couple of albums – Julian Lennon, Aretha Franklin. People just loved the town and the players.

“Paul would come back with tracks, and I would overdub stuff. There’s some wonderful songs on the album. Paul was very driven. I think the separation of Simon & Garfunkel had become a challenge. People thought the two of them wrote the songs, but as we all know, Paul was the writer.

“He’s very mysterious and meticulous. Nothing goes quickly with Paul. Like it is with a few artists, you might only get four bars of music in an afternoon, but they’re four great bars.”

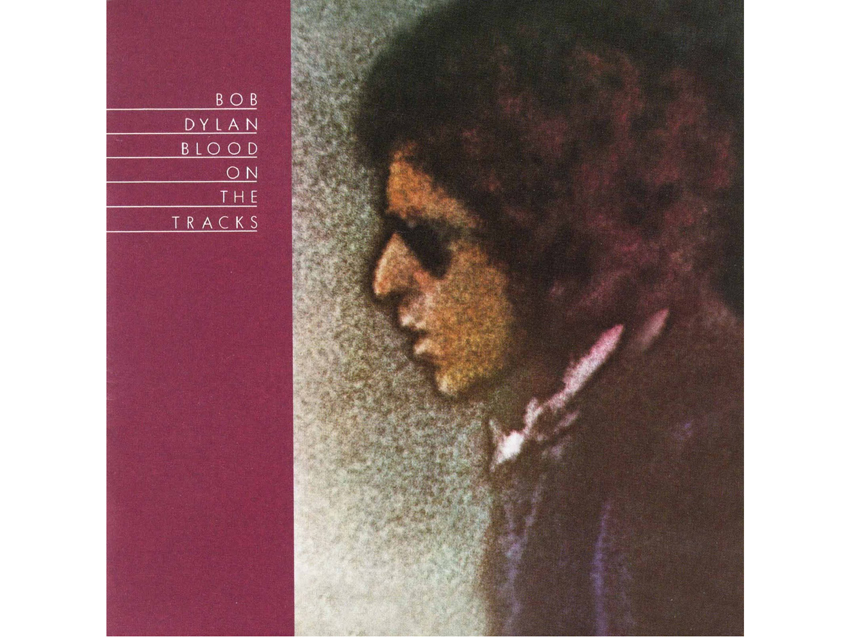

Bob Dylan - Blood On The Tracks (1975)

“I got a call one day from John Hammond, one of the real legendary men in the record business: ‘Bob is coming back to Columbia Records, and I want you to be a part of it.’ It turned out to be the best four days of what Bob Dylan does, which is he wanders from song to song, sometimes coming back to the first one. Other than changing the roll of tape, you just had to let it all happen.

“It’s what I learned in my early days: You have to keep your ears open and be receptive to what’s happening even in the beginning stages. If you listen to the album, you can hear his pick hitting against the mic or something else happening. One of the guys in the room turned to me and said, ‘Did you hear that? Aren’t you going to fix it?’ I told him, ‘When we take a break – maybe.’ You don’t mess with Bob’s performance.”

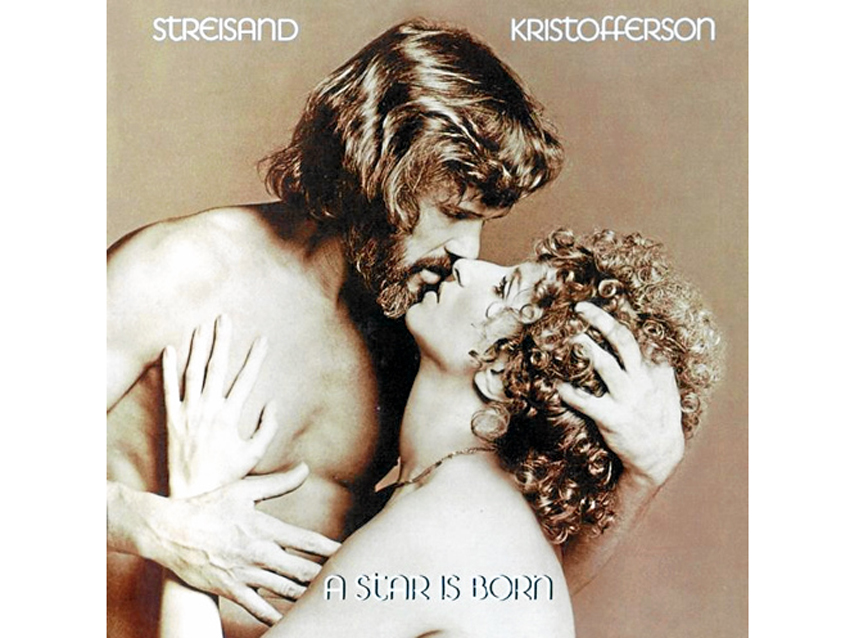

A Star Is Born - Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (1976)

“A wonderfully challenging record. Barbra called and asked me to get involved because I had done a project with her called A Happening In Central Park. That was the first type of show where you had upwards of 25,000 people, kind of the precursor of what became Woodstock and other events.

“Barbra had always wanted to do a picture live. She wanted me to design the production for recording. We had a truck that had allowed us to tie two 24-track machines together. It had never been done before. Warner Brothers and First Artists were pretty nervous about it: ‘What if she gets laryngitis? What if the band doesn’t play right? We can’t take chances like that.’

“We built the whole thing, and we recorded and filmed as a band that traveled with her. The band got as tight as any touring unit I’d ever seen. A lot of the players were from Kris Kristofferson’s band. I put a couple of other musicians and horns in. It worked.

“In order for us to convince the film people, we shot at a club and recorded everything. There was no overdubbing – when Barbra sang with the band, it was all live. The next day we played it for the brass, and they got up and applauded.”

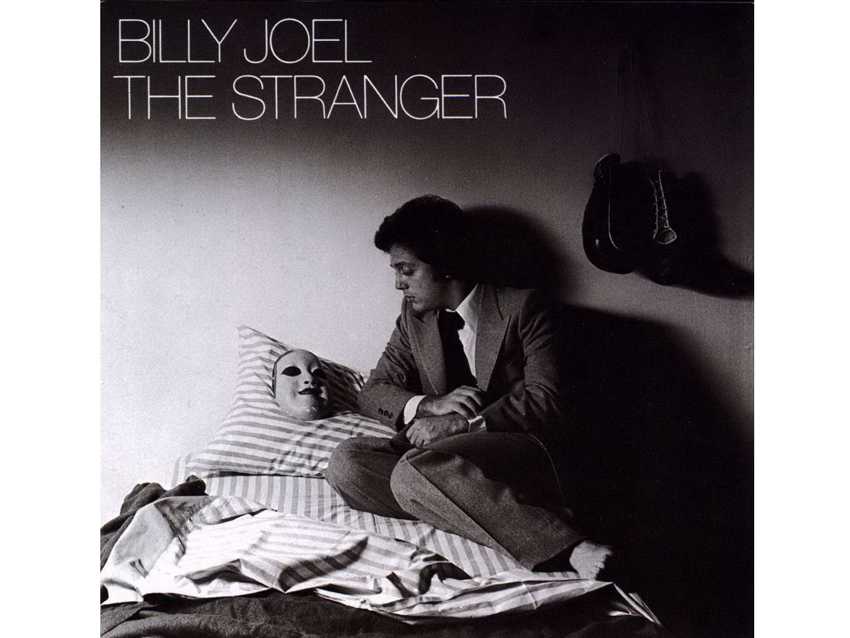

Billy Joel - The Stranger (1977)

“I had seen Billy play a Columbia Records convention. He opened the show, Paul Simon was second and Phoebe Snow was third. He obliterated the place. He was just... unbelievable.

“Later, after I saw him play Carnegie Hall, the two of us had lunch. I didn’t know I was being auditioned. There was somebody else [under consideration], I think... this young guy from England named George Martin. [Laughs] Billy and I had a great Italian lunch, and he said, ‘What do you think is right for me?’ I spoke my mind and said, ‘Billy, I’ve listened to your albums, and I don’t hear the energy that comes off that stage.’ Sooner than I expected, I got a call: ‘Can you go into the studio with him?’

“We got along great. We’re both lunatics, of course, so that helped. But there was something uncanny about him and his talent. The energy that he had on stage is what I wanted to get on tape.”

Billy Joel - Glass Houses (1980)

“This album represented the desire to get something that was very dry, with no effects. There’s a song on it called It’s Still Rock And Roll To Me, and that’s the essence of the whole record. It’s about how good and how simple and how rock ‘n’ roll Billy could be.

“There was a lot being said about Billy at the time – he wasn't this, he wasn't that. I remember we were sitting around and talking about his first album, which was sped up by the producer. He sounded like a young folkie, like somebody you’d hear in a club down in the Village.

“The record is tough, and it’s genuinely him. We were not going to give in to slickness. It’s very real and aggressive, and it shows how great his band could play. There’s a lot of meaning in the album.”

Julian Lennon - Valotte (1984)

“I met Julian in London a few years before we made the album. He was signed to Atlantic in America. Ahmet Ertegun, who was one of the great pioneers in recording, wasn’t happy with what was going on, so I suggested we go down to Muscle Shoals and work down there for a while.

“The idea was to get Julian comfortable and just be ‘Julian Lennon,’ not ‘John Lennon’s son.’ We got the usage of the band and the Muscle Shoals sound. Eventually, we went back to New York, where we did Too Late For Goodbyes.

“Julian suffered a lot. The critics, in a good sense, compared him to John. On his second album, he wanted to sound different, and it became like this animated guy playing him instead of just being Julian. I don’t know what it might be like to have to compete with such a famous father. It’s almost impossible to get through that wall.”

Frank Sinatra - Duets (1993)

“A major, major album for me. Frank hadn’t made a record in a long time. It took a year to convince him to do it. Quincy helped me, his manager helped me. Frank and I would meet up in Palm Springs, Palm Beach, Palm somewhere – Palm Sunday. [Laughs] I had him almost ready to do a live recording in New York, and eventually I came at him with a different concept: duets.

“He bought into it, but he was constantly checking me, checking why. I remember Mo Ostin told me, ‘Be careful. If you book the studio, he’s likely to come in and leave.’ Which he did – he came in, got uncomfortable, and he left. Eventually, it started happening.

“I put a list of artists together for Frank to ‘duet’ with; he didn’t sing live with anybody. But I'll tell you, when we did the first date with Frank, it was pretty amazing. It brought such a smile to his face. He said, ‘I don’t know how you do this. I didn’t believe you could.’ The whole thing was like putting the greatest canvas of a crossword puzzle together.

“None of the singers held back. Because of the way we recorded it, we could switch around when Frank sang and when he didn’t. He had pretty much given us carte blanche to do what we wanted. The funny thing is, everybody was betting against this record: ‘You can’t do a duets record if they’re not singing together in the same room. It’s not believable.’ The counterpoint to that is, years later, I did a duets record with Tony Bennett with everybody live in the room, because Tony hated not being in the same room with Frank.

“Frank was very happy with the album, and we took a lot of pride in his feelings for it. We got some criticism for some things, but I look at it as the artists’ interpretations of what it was like to sing with Frank Sinatra.”

Ray Charles - Genius Loves Company (2004)

“Ray wanted to record back in his room in downtown Los Angeles. We had fixed up the room and painted it just for the movie that Taylor Hackford was shooting – this was going on simultaneously. It wasn’t the most wonderfully equipped room. There was still some stuff in there from the ‘60s, but with some adjustments and careful planning, it really wasn’t changed. We let it be, with the leakage and all.

“I went out and bought a huge beach umbrella and put some deadening material under it. This allowed Ray to hear the drums better, but we could still control the leakage into his vocal mic.

“Part of what Ray was used to, and it was true anytime we worked together, was going for the live thing. Sometimes he didn’t want the piano miked, because he said that the guys running the PA system didn’t understand what he wanted. It was all about making him comfortable in the room. Many of the people came by to sing live with him.

“He was still a powerful performer, but his health started to fade. When he did Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word with Elton John, a couple of the people had little amateur cameras on them, and they panned the room to see that we were all in tears. At the end of the song, Ray asked me, ‘You got enough?’ I said, ‘Yeah, it’s beautiful.’

“Elton walked in the control room, and he was in tears, too, because you kind of knew… this could be the last chance. And that was Ray’s last record.”

Paul Simon - So Beautiful Or So What (2011)

“It was great to reconnect with Paul. I had gotten involved with him during his week of African nights at the Brooklyn Academy Of Music, and then there was his show The Capeman and a week of American Tunes, and so one day he said, ‘Come over to the house. I want to play you a couple of things.’ So that's what started So Beautiful. Over a period of 12 months, we made the album. I think it’s one of the better records he’s made in a long time. There’s nothing as special as a Paul Simon record.

“I felt he could sing better than ever. We did some exceptional vocals. He composed from the top down, so it wasn’t all about the rhythms. In fact, there’s very little bass on the album. The bass notes are coming from the guitar. It's always interesting with Paul. There’s things like bells and all kinds of overtones – so much atmosphere. He didn’t want it to sound like a stock studio album, and it doesn’t.”

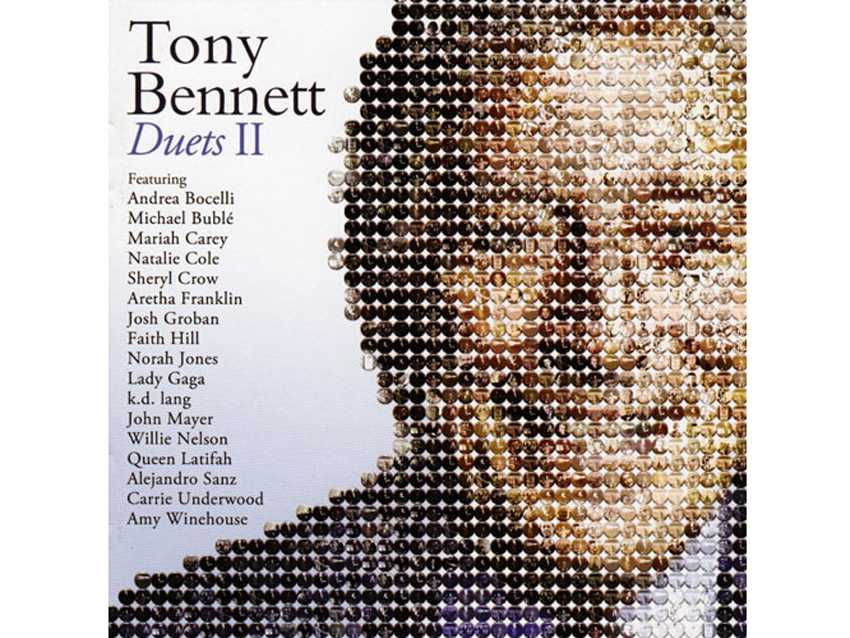

Tony Bennett - Duets II (2011)

“Having an 85-year-old guy sing better than he did when he was 80 really makes you think about how to preserve one’s life. He also comes from the Frank Sinatra school of doing things quickly, in the fewest amount of takes possible. But he’s a complete gentleman to the youth.

“Danny, his son, and Dae Bennett, his other son who was the engineer, co-produced the album. This let us surround Tony in comfort. The fact that they also made a documentary is amazing, because there were quite a few times when they had to stay out of the way when they needed the shot.

“The list of performers on the album came from Danny. We needed to represent the youth, but it was funny because Tony would look at the names and say, ‘Why do they want to sing with me?’

“The recording of Amy Winehouse was very difficult for the obvious... and we were worried about it. Amy really loved Tony – she had been to many of his shows. She was scared, but she was also a wonderfully attentive student. Tony and I talked with her about how we heard Dinah Washington in the way she interpreted the song. In the world that I live in, having Dinah Washington on your side is pretty special.

“There’s a point in the documentary where Amy gets so nervous and uncomfortable. She says, ‘That’s not good enough. I can do it better.’ She signals to stop the cameras, and asks for them to leave the room, which they do. That’s when the performance starts to come.

“Amy and Tony were so youthful together. There was such a history of sound coming from the two of them.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.