Production legend Ken Scott on 10 career-defining records

In 1968, at the advanced age of 21, Ken Scott sat dead center in what was regarded as the epicenter of the world – Studio Two at EMI Studios in London - when he replaced Geoff Emerick as The Beatles’ engineer for the sprawling double album that would become known as the ‘White Album.’

A year earlier, the former tape logger and second engineer had his first big break when he manned the console on some sessions for Magical Mystery Tour, an experience Scott calls “daunting. I had never sat behind a board or pushed up a fader before the first session I did with The Beatles. I was terrified. I had no idea what the hell what I was doing.”

Having joined the staff at EMI at 16 (“I wrote them a letter and a week later I started work”), Scott learned to think on his feet and was a quick study. “It was a fantastic studio to learn your craft,” he says. “In one place, you had three of the greatest classical engineers and three or four of the greatest pop engineers. I soaked it all up.”

Soon after the White Album, Scott added production to his skill set, and over the years he’s produced, engineered and mixed (sometimes all three) records by a staggering number of artists, including George Harrison, John Lennon, Ringo Starr, David Bowie, Jeff Beck, Elton John, Stanley Clarke, Dixie Dregs, Elton John, Devo, Supertramp, and others.

Scott recounts his life behind the studio glass in a captivating new book (written with Bobby Owsinski) called Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust: Off The Record With The Beatles, Bowie, Elton & So Much More, due out 6 June via Alfred Music Publishing. (It's available for pre-order here.)

Numerous first and second-hand accounts of The Beatles have been written over the years, many of them dwelling on the final days of the band and the contentious atmosphere that attended the recording of the White Album. In his book, however, Scott takes issue with some of these stories, insisting that the White Album sessions were “a lot of fun. We had a blast.”

On the following pages, Scott offers further details on the White Album, along with nine other memorable albums from what has certainly been a brilliant career. "I'm extremely fortunate," he says. "I knew what I wanted to do since I was 12, and I've had a great time doing it."

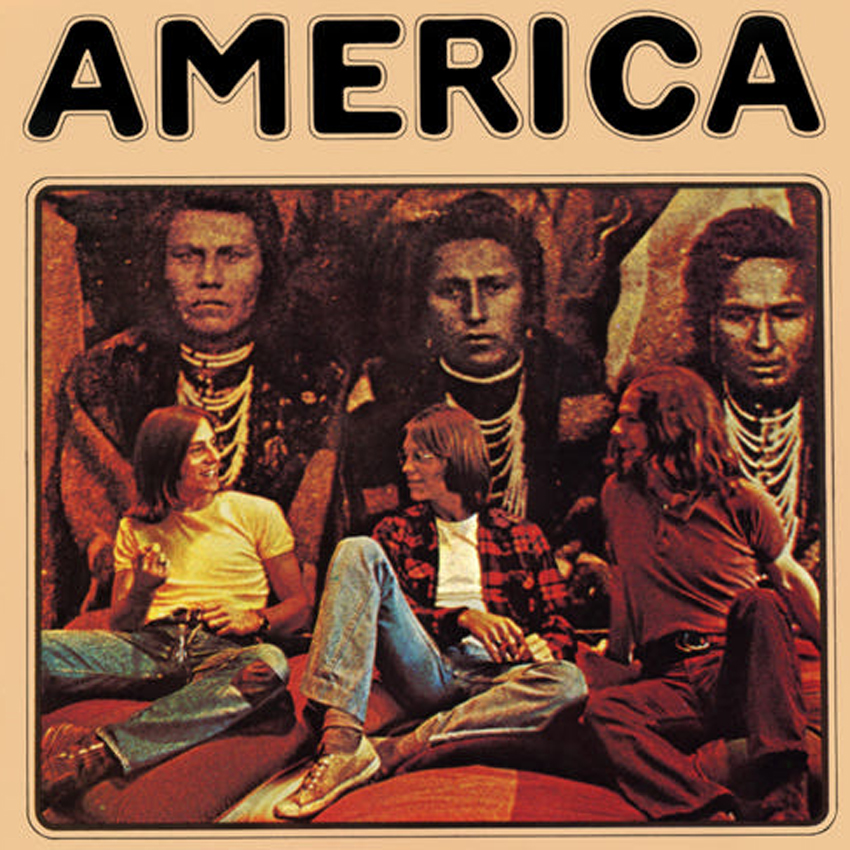

America - America (1971)

“The group was totally wet behind the ears, but they were sweethearts. During these sessions, I did learn how to deal with the difficulty of co-producers, because Jeff Dexter and Ian Samwell, who were producing the album, had differing ideas of a lot of the time. From this point on, I learned that I could never deal with that sort of thing again.

“America were from America, and they were making American music, but it was emanating from England. That side of it felt kind of weird, because normally there’s a vast difference between the stars of England and the States.

“They were cool, totally great. I really loved working with them.”

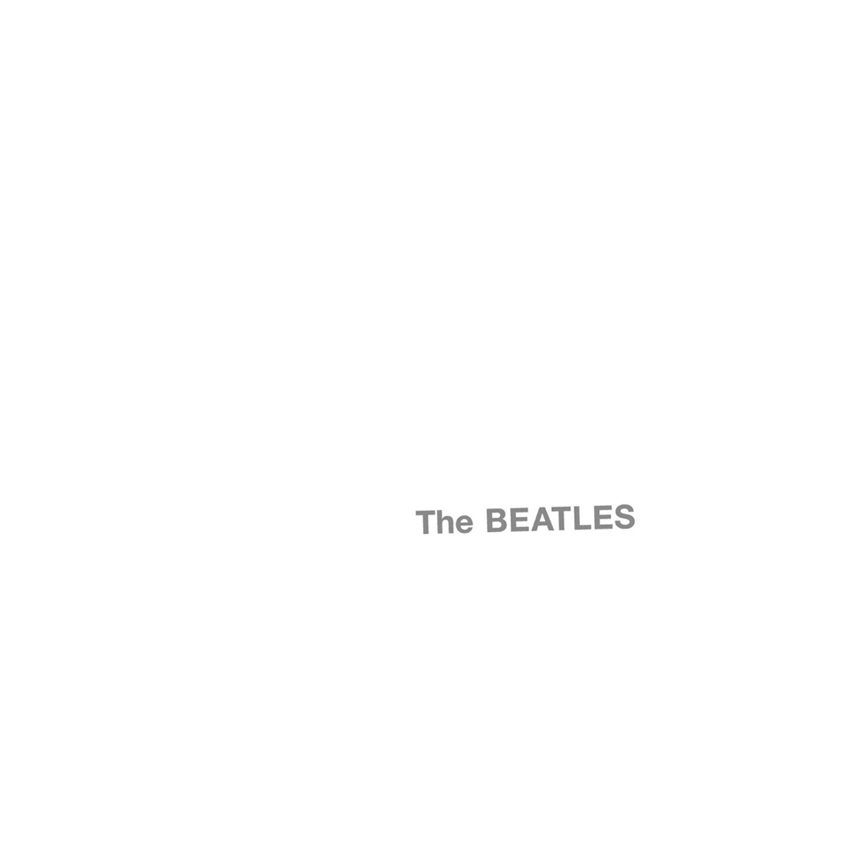

The Beatles - The Beatles (aka the 'White Album') (1968)

“We had a blast in the studio. I know that stories have been out over the years about what a horrible experience the White Album was, but we had so much fun. It was great.

“Sure, there were arguments. I haven’t worked on any project where somebody doesn’t lose their temper. They’re artists; they’re going to get temperamental – it happens. But to say that the whole thing was dour and terrible, that’s bullshit.

“Even when Ringo walked out, which he did for a couple of days, it wasn’t out of anger. He was feeling unloved. He didn't feel like he was needed. The Beatles were at the point where they were talking one another for granted.

“From an engineering standpoint, working with them was easy. I couldn’t make a mistake if I tried. The Beatles never wanted anything to sound the same, so if I chose a completely off-the-wall mic, put it on a piano in a very strange position, pulled up the fader and it sounded terrible, there was every likelihood The Beatles would say, ‘That’s great! It sounds like anything but a piano. We’ll use it.’

“On Savoy Truffle, one of George Harrison’s songs, I got what I thought was a really good sax sound. George came in, listened to it and said, ‘That’s great – distort it.’ For a second, I was like, ‘Oh, noooo.’ But it worked.

“It was a big album. Right from the start, we could tell there was a lot of material. It was more basic than Sgt. Pepper, more rock ‘n’ roll. Luckily, I didn’t do Revolution 9. That’s one of the tracks Geoff Emerick did before me. Maybe that’s why he quit!”

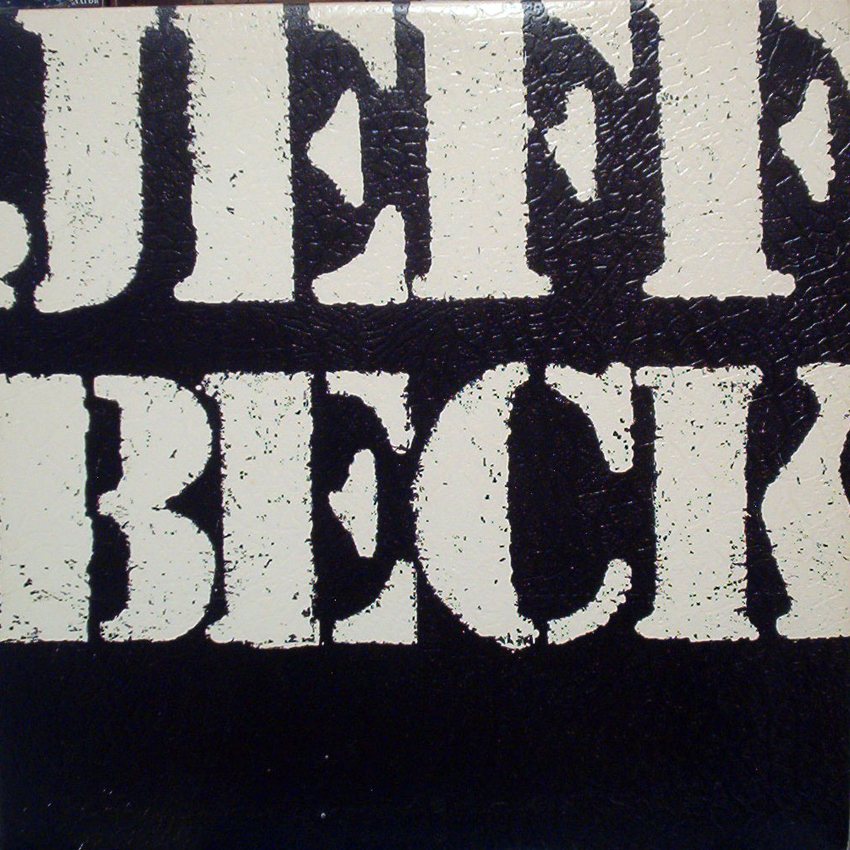

Jeff Beck - There And Back (1980)

“I did the Truth album with Jeff years earlier. At the time, he and the band were real sweethearts in the studio. Then they went on tour and were hailed as gods, particularly in America, and it really went to their heads. We started the next album and the egos were enormous, just out the door. They were impossible. I think we worked together for one day before the project ended.

“Through the years, I’d worked with Jeff on some projects, especially some Stanley Clarke albums, and he became a normal guy again. When we started There & Back, he went another way totally – for the first time, he was insecure. He was very nervous about being as good as the other musicians he was playing with. It was anti-ego. I had to build him up and reassure him. It was strange.

“I love the song The Pump, especially Simon Phillips’ drum sound. On a Stanley Clarke album, I formulated this technique of miking the bass drum by suspending the mic inside the drum, and then I put both heads on. A fantastic sound.”

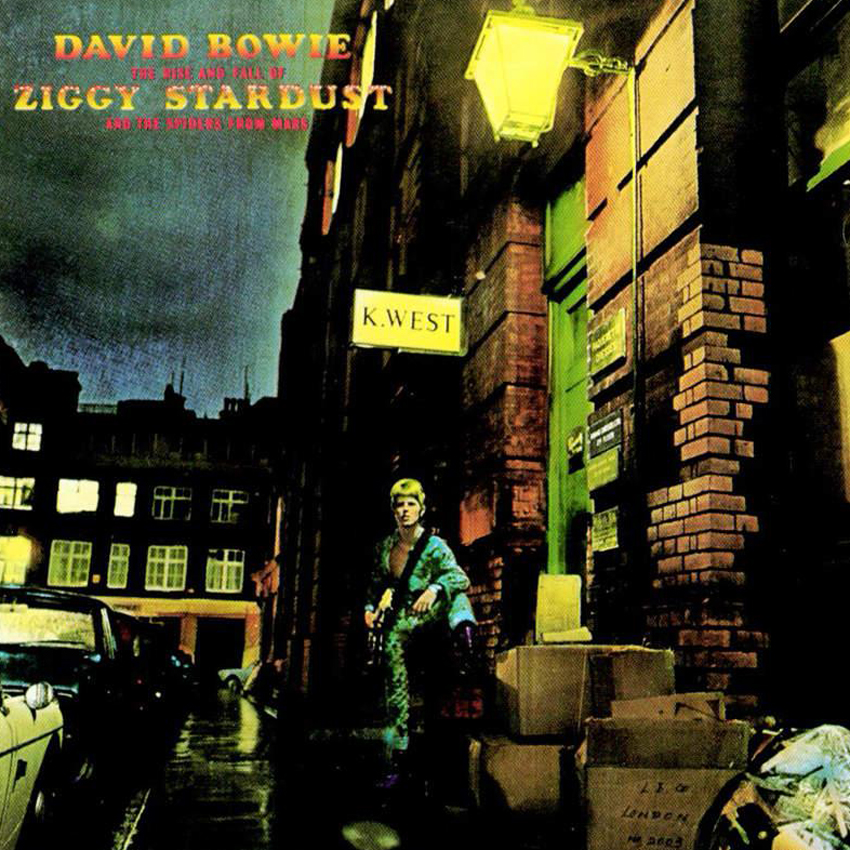

David Bowie - The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars (1972)

“I really don’t understand the acclaim for this album. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a great record, but I’m shocked to be talking about it 40 years later. When we made it, we would’ve been happy if people remembered it after six months. That’s what we expected of all records back then.

“I had produced the previous album, Hunky Dory, but before that David had worked with Tony Visconti. I think why David moved to me was that Tony, as a musician in the band, was controlling everything with the vocals. David needed to find his own road, his own ideas.

“Working with George Martin, I learned how to let the artist create. You let them go as far as they can. If they lose track of things, that’s when you pull them back.

“David had his characters over the course of his career, but the whole Ziggy persona wasn’t going on at the start of the album – it came later. When we were in the studio, he was just David Jones. But you know, it’s like your kids: You don’t see the changes every day. It’s not until somebody comes by who hasn’t seen them in a while and they go, ‘My, how you’ve changed!’

“Working with Mick Ronson was great. Ronno was such a lovely guy – and a brilliant, intuitive guitarist. I didn’t have to do anything special with him, really. He played through a Marshall, but he had a wah-wah pedal before it. He found the wah setting he liked and left it there. All his sounds came just like that.”

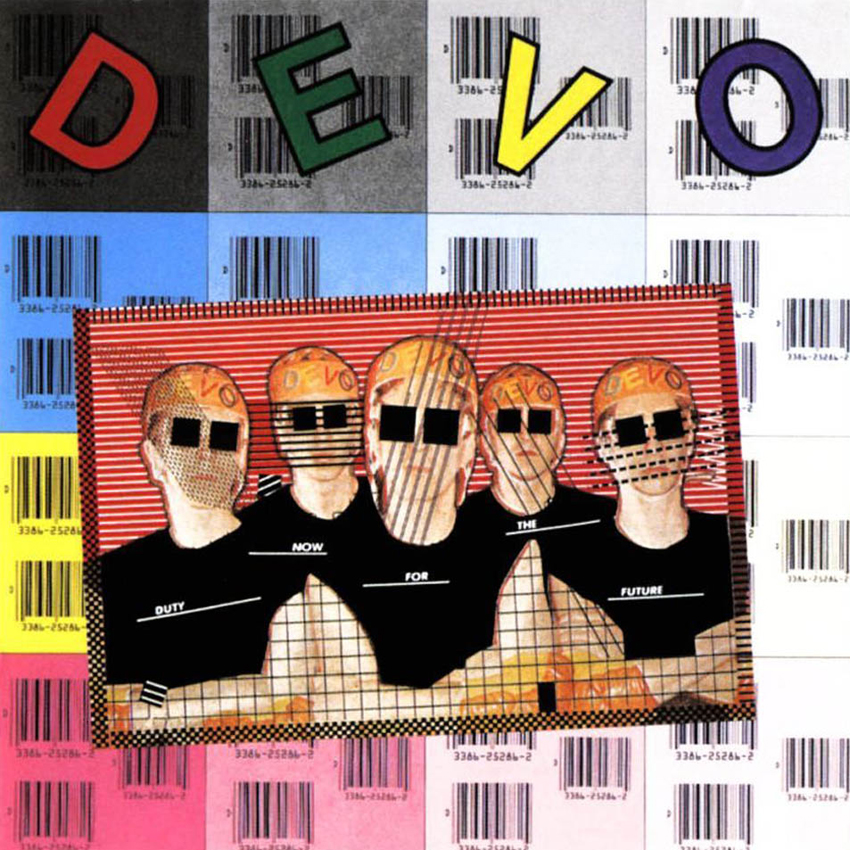

Devo - Duty Now For The Future (1979)

“When I first heard the band, I thought they were a load of crap. But then I saw them on Saturday Night Live, and that’s what did it for me. Seeing them and hearing them, I got it, and I loved it.

“The synths, to me, were just another instrument. It was all a matter of finding the right tones to work with. We used three different drum kits because we wanted a different sound on certain songs – each song was taken as its own entity.

“Devo were very professional and easy to get along with, not like their stage persona at all, except on one occasion: The owner of the studio wanted to show somebody the room – this guy wanted to book some time – and suddenly Mark Mothersbaugh acted like he did on stage, screaming and running around and being crazy. It was weird. The second everybody left, Mark went back to normal and we resumed working."

Dixie Dregs - What If (1978)

“I really loved what they were doing. They had a bit of the Mahavishnu Orchestra in them, they had country, and there was some funk, too, with songs like Ice Cakes. They were fascinating.

“Steve Morse is the greatest guitarist I have ever worked with. He has the chops of a John McLaughlin, and he can play just as many notes, but he knows when to do it and when to pull back. If a solo would work with one note, that’s what Steve would do.

“Rod [Morgenstein] is an amazing drummer, but he’s grunter – meaning he grunts when he plays. While we were recording, we heard these strange sounds on his takes. We went through mic after mic trying to find the problem, and finally we realized that the sounds were from Rod grunting when he played. We asked him to stop, but he couldn’t.

“For a lot of the tracks, we ended up putting gaffer’s tape over his mouth to quiet him down. But for Ice Cakes, we really liked what he was doing, so we gave him his own vocal mic.”

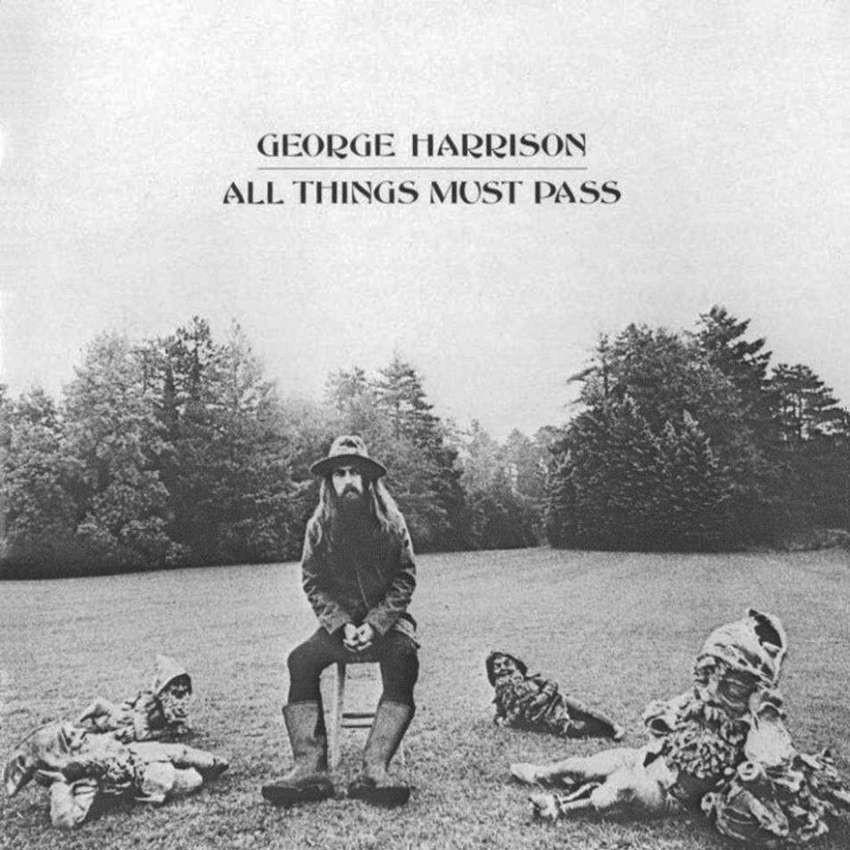

George Harrison - All Things Must Pass (1970)

“When I worked with George on the remastering of the album, I spent time with him in Friar Park, his place in England. We put a tape up, started listening and just burst out laughing.

“There were two reasons: One was because we were sitting in exactly the same positions, listening to exactly the same song, as we were 30 years prior. It was ridiculous. But the other reason was when we went, ‘My God, did we really put that much reverb on there? That’s atrocious!’ We would have loved to have been able to remix it, like what was done on the Let It Be…Naked album, where the Phil Spector sound was taken off.

“I didn’t do the basic tracks on the original album, but I worked with George on the overdubs and the mixing. It was really just me and George for that. Phil Spector had left, and he only came back when it was time to mix – and even then he was only around for brief periods each day.

“It was pretty amazing doing the backing vocals, because on all of the tracks, all of the backing vocals are George. We’d record him doing a part four times, then I’d bounce those tracks to one track with him singing live. Then we’d start on the next harmony, doing it the same way. We just built them all up. It was painstaking, it took a lot of time, but it was great.

“When we were making the album, we didn’t think it was over the top. It was fine, it was exactly what we wanted to do – at that time.”

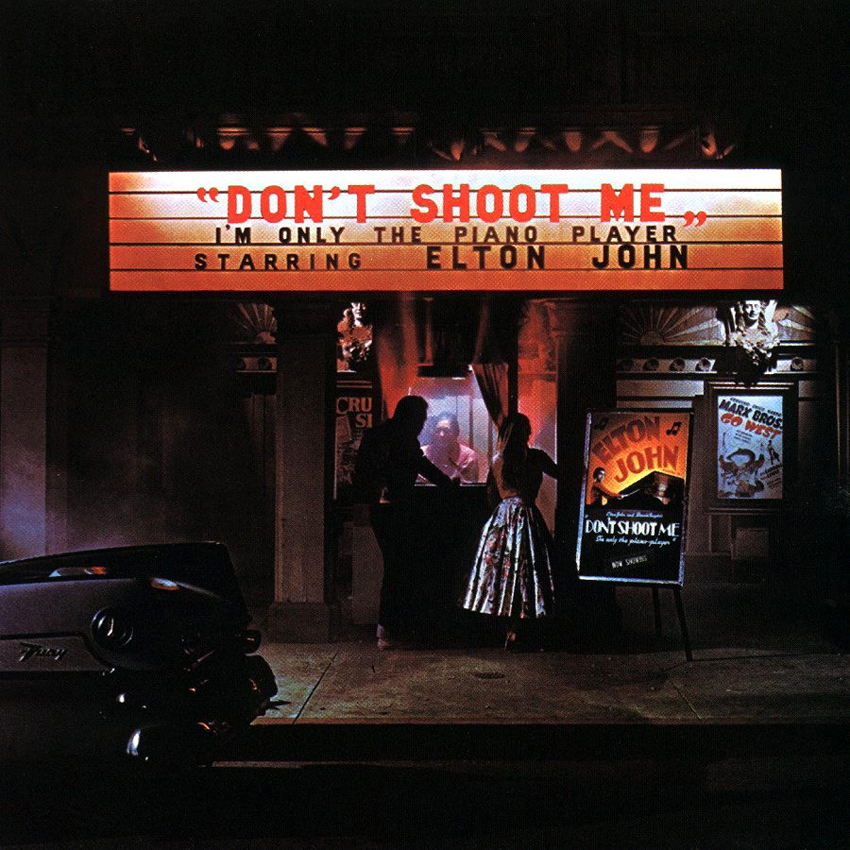

Elton John - Don't Shoot Me I'm Only The Piano Player (1972)

“We had done the Honky Chateau album in France, which was a lot of fun, and so this album was very much the continuation.

“Elton’s piano sound is quite unique. In the early days at Trident, he was playing a Bechstein, which was built in the 1840s. It was the most incredible piano I’ve ever worked with – very hard, but with a real bite. For classical music, it was terrible; for rock ‘n’ roll, it was superb.

“We had to try and match that sound in France. I can’t remember what piano was in the studio. It was good, but nothing was like the Bechstein. I would mic the piano with a Neumann U67 on the low end and a Neumann K84 or 86 on the high end.

“Trident had a separate drum booth, whereas the studio in France didn’t. We immediately knew that [drummer] Nigel [Olsson] would be picked up like mad on the piano mics because they cut performances live, so we had to build this huge wooden box built that we put overtop the piano. It had holes built in for the mics, and it completely blocked out other sounds.

“You knew the songs would be smashes. It’s easier to hear that with an artist who’s already well known. If it had been an unknown singing these songs, you’d go, ‘Well, they’re great songs.’ But because Elton was already successful, you knew they would be big.”

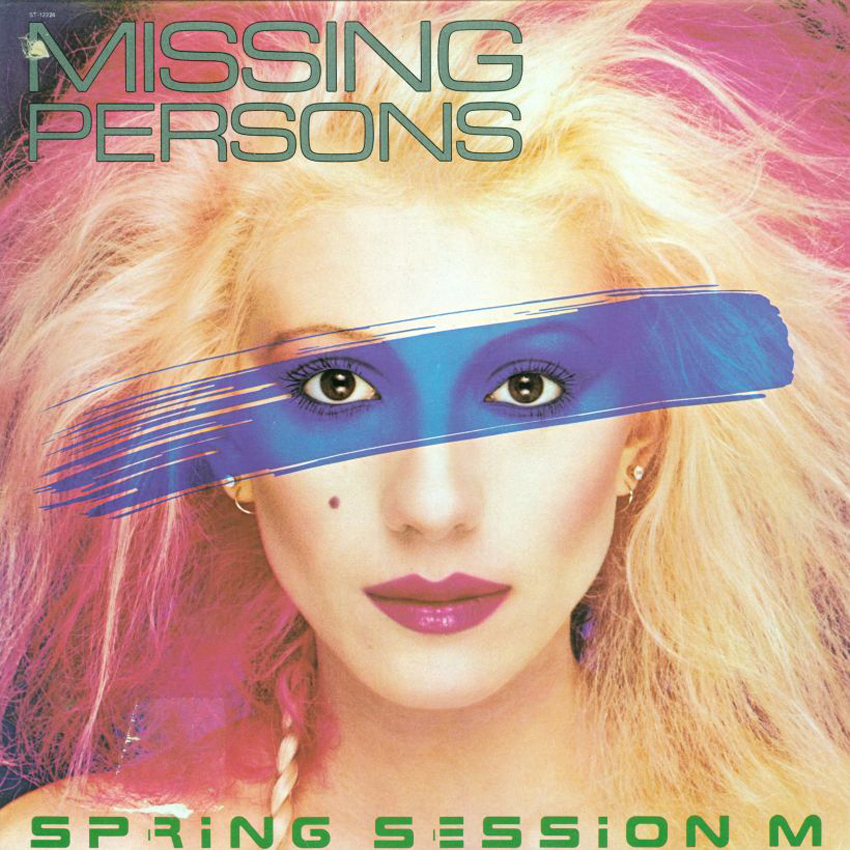

Missing Persons - Spring Session M (1982)

“I got a call from Frank Zappa’s wife, who told me, ‘I’ve got Terry Bozzio, Warren Cuccurullo and Terry’s wife here. They’ve just formed a band. Would you mind listening to them?’ I said, ‘Sure, send them over.’ So they came by with their boom box tape, which I listened to, and I thought it was utter shit.

“They said they didn’t play live shows, so I went to see them in rehearsal, and once again, it was awful. I don’t know what it was that kept me interested. I guess it was Terry Bozzio, who I’d seen play with Frank Zappa. I was utterly blown away by him. I must have thought, Terry can’t be in something that’s bad. So I said, ‘Let’s do some demos.’

“Frank had just had a studio built in his home, and he allowed us to use the place when he went out on the road. Knowing my reputation for finding the tiniest faults in every studio and fixing them, I can only imagine that his ulterior motive was that he could come back to his studio and have everything made perfect and ready to go.

“We got five songs done for free, tried to shop a deal, and nobody was interested. So we put out our own EP and it became the most-requested record of the year on K-Rock. We were then offered a deal by Capital, so we went in to Chateau Recorders to finish the album, which was Spring Session M. By this point, I was managing the band, as well as engineering and producing them. We did 800,000 sales straight away. The album was very successful.”

Supertramp - Crime Of The Century (1974)

“I don’t know what got into my head: I decided to slow the pace of doing things in the studio, so we’d spend a day and a half getting a drum sound. After about two weeks, we had some basic tracks, maybe a couple of overdubs, but nowhere near the finished album.

“That’s when we got a phone call that Jerry Moss – the M of A&M Records – was in town and wanted to come by and hear the album. I tried to tell them that we weren’t ready, but that was it: Jerry’s coming. I quickly got some rough mixes together.

“Jerry came in, sat down in front of desk at Trident, and we played him what we had. At the end of it, he got up, shook our hands, said ‘Thank you’ and left. I thought, That’s it, we’re done, he’s pulling the plug. We almost didn’t turn up the next day, but I’m glad we did. We got a phone call – ‘Jerry loved it. Whatever you need – time, money, whatever – just let us know. Keep up the good work.’

“I got very creative with sounds on this album. I didn’t want to use typical percussion instruments, so we’d bang on sofas, cardboard boxes – at one point, I was down on my hands and knees, trying to find the right spot on the wood floor for the perfect sound. This was before computers, so we had to make our own sounds. It all came out quite good.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.