Producer Jack Douglas talks about 18 career-defining records

Jack Douglas realized he had the best job in the world not when he received his first gold record, nor when he was handed his first platinum disc. It wasn't even when he posed with his first multi-platinum award – and he has tons of those too. It was back in the late '60s, when, as a low-paid "general worker" at the Record Plant Studios in New York, he encountered rock royalty.

"Jimi Hendrix offered me a joint in the studio," Douglas says with a laugh. "I thought, This is unbelievable! What a great job I have. And it just got better and better.”

Douglas quickly rose through the ranks to engineer, and it wasn't long till he was producing a glittering array of artists such as Aerosmith, Cheap Trick, Patti Smith and his hero, John Lennon. In some cases, he was on to a bands first or very early in their careers. At all times, his criteria for working with an act remained constant.

“I look for originality," Douglas says. "But I also want something completely different from the album I just finished. A band has to have something about them that makes me go, ‘Wow, that’s new!’ It helps to keep me fresh. Also, the band won’t suffer from me repeating the same tricks I just used on the record before theirs."

In this day and age where more importance is placed on singles over albums, Douglas' view on on the art form of the long-player is the same as when he began cutting tracks. "I’m not a big singles guy," he says. "I’ve always liked albums, and that’s what I want to make." By his own assessment, he's only called a single once: John Lennon's (Just Like) Starting Over. "That one was so obvious," he says. "The minute I heard it, I knew."

Beyond hit songs, Douglas says that the human aspect of vocal chops and hands on instruments is key to a spectacular recording. "You can’t have a great album without people playing and singing the hell out of a tune," he says. "There’s many ways to get a real performance – new ways, old ways, in-between ways – and my belief is, whatever it takes. I want a record to sound like the band is really playing, not like it’s all coming from a computer."

Although his credits are drool-worthy by any stretch, the producer does admit that a few choice acts have eluded him, chief among them The Rolling Stones. "I know all of the guys, Mick is a friend, and I’ve worked with Ronnie Wood," Douglas says. "There was a chance to get in there, but that’s when they started working with Don Was – and he does a great job with them, so there’s no reason to try to upset that cart."

Even without a Stones plaque hanging on his wall, he's done well for himself, and on the following pages, Douglas shares the stories behind 18 of his most memorable records.

John Lennon - Imagine (1971)

“I traveled to Liverpool in 1965, and I ended up getting held hostage on a ship. It’s a crazy story, but I managed to escape. I was all over the Liverpool newspapers. There was so much interest in me, being that I was this kid from American kid and all.

“I went over there because I wanted to be a part of what was going on with the music in the mid-‘60s. Rubber Soul came out the day I escaped, and I bought it that same day – in Liverpool. I thought that was pretty cool. I ended up getting deported too.

“Some years later, I’m working at the Record Plant. I was an engineer on the cusp, so I was assisting while cutting demos for Billy Joel and Labelle and some other people. I did a lot of editing. One of my jobs was to transfer these two-tracks that John Lennon cut in England to multi-tracks so he could do overdubs in New York. These would be 16-track. I was hearing a lot of the songs before anybody else was, which was a thrill. I was a massive fan of his.

“About a week into this, John walked into the room. He was looking for a place to get away from everything. He wanted to just sit. On the other side of the console was a couch, so he sat there, and all I could see were his shoes and his cigarette smoke.

“After about 10 minutes, I got up the courage to tell him that I’d been to Liverpool. His head popped up. ‘You’ve been to Liverpool?’ he said. ‘Why on earth would you go there? It’s a dirty, terrible place. Where are you from?’ I said, ‘I’m from New York.’ And then I told him the story, how I went over because I loved the music and I wanted to get involved with it, how I ended up getting deported. He just looked at me and said, ‘You weren’t that crazy Yank, were you? That was in all the papers!’

“He got really excited to meet me. It was amazing. He invited me into the tracking rooms, he gave me a ride home in his limo. Pretty soon, I was working on the record as an assistant. We became friends.”

New York Dolls - New York Dolls (1973)

“Being a downtown guy, I used to hang out at Max’s a lot. I knew the whole scene – the people, the music. Todd Rundgren was producing the Dolls record, but he’s an uptown guy. He liked the big harmonies and the big production.

“This was a different kind of record. Nobody had never even heard this kind of music before. There was no category called ‘punk’ yet. There wasn’t even glam. The Dolls were cutting edge. They couldn’t play, but it was about their attitude and songwriting. They were pretty fucked-up on drugs. It was a different scene from what Todd was used to.

“One day, David Johansen was doing a vocal. He came into the control room after doing the tracking, and Todd said to him, ‘That’s going to sound good after we put lots of harmony on.’ David just looked at him and said, ‘Harmony? Are you accusing me of having melody?’

“Right then, it became clear that this was not going to be a good combination. So Todd didn’t come in a whole lot, but we managed to get the record done. It became a classic. The payoff for me was that Bob Ezrin convinced me that I should try producing, because I was actively working with the Dolls. And the second thing that happened was, the management company for the band, Lieber & Krebs, said that they had a baby band I might want to produce.

“That baby band turned out to be Aerosmith.”

Aerosmith - Get Your Wings (1974)

“I went up to see the band play at a high school just outside of Boston, and I fell in love with them immediately. They reminded me of The Yardbirds. They were raw and noisy and totally cool. Steven was such a good singer.

“After the show, I went back to their dressing room and started talking with them, and we hit it off right away. We spoke the same language, loved the same music, we loved guitars – I could tell this would be a good match.

“Doing the record was a bit of a training session for all of us. On both sides, we were getting our wings. Their first album was great, but Steven sang in this high voice, so I wanted to fix that and let him be himself.

“On Same Old Song And Dance, I told them that we should bring in some horns to bring out their rhythm and blues side. They definitely had that kind of style and sound already. We got the Brecker Brothers to play on that. The sax solo is Michael Brecker.

“Train Kept A-Rollin’ was a showpiece for them at their live shows. That was the Yardbirds song from the movie Blow-Up. For the live audience sounds, we used what was on the Concert For Bangladesh – it wasn’t from a real live show. I can’t remember if everybody was into that or not at the time. You had the band and you had Steven.” [Laughs]

Aerosmith - Toys In The Attic (1975)

“The band went out on toured, and by the time we got ready for pre-production, they didn’t really have any new material. So it was just little gems of things that they were noodling with, and we would turn them into songs. We’d didn’t worry about lyrics, as long as there were melody lines and we had something phonetic to work with.

“Even with the lack of songs, the band had improved dramatically from Get Your Wings. They were like a brand-new group. You could tell that they were about to take a giant step forward. They weren’t puppies anymore – now they could really play.

“We spent two months in Boston doing pre-production, and then we went to the Record Plant to make the record. The only song we didn’t have a melody for was Walk This Way. We had the riff, we had a track, but there was nothing for Steven to sing over. It almost felt too rhythmic. It wasn’t working, and we were going to dump it. It was not going to go on the record.

“Steven and I used to go out for walks. We did this a lot whenever he needed lyrics. We did the same walk around the same blocks in New York. So one day, the whole band and I went out. We're walking around, doing the same routine, only this time we ended up going to a movie – Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks. There’s that scene where Marty Feldman as the hunchback says, ‘Walk this way.’ That struck us as being very funny.

“We went back to the studio, and I started joking around, going, ‘Walk this way, walk this way,’ doing it in these funny voices. We were all laughing. Steven said, ‘I’ll be right back.’ He liked to go sit in this stairway to work on lyrics. Within an hour, he was back with the lyrics to Walk This Way. After that, we had it.”

Aerosmith - Rocks (1976)

“Rocks is one of my favorites, but again, there was no material at first. The band had been on the road touring Toys In The Attic. Slowly, ideas started getting tossed around. Tom Hamilton wrote the music for Sweet Emotion. He had that bassline, and when Joey Kramer came in, he played on the twos and fours instead of the ones and threes, so he was playing on the backside of it. When we heard that, we went, ‘Oh, boy! Magic… ’ We knew it something special.

“We spent three or four months in pre-production. The pressure was on us to come up with something better than or at least comparable to Toys. We were rehearsing in this big warehouse, and to try to make the place sound decent, I hung up these carpets and laid down rugs – anything I could do. It took a while to get a good sound.

“In a way, doing those things worked for the overall sound of the record, because the music that was being created was done so to fit the room. We didn’t do it on purpose, but particular keys or riffs just sounded right in that warehouse. Finally, I said that we weren’t going to go to New York to record – we were going to stay right there and do it. I brought in a remote truck. The vibe stayed the same while we recorded those basic tracks, and it really contributed to the magic on Rocks.”

Patti Smith - Radio Ethiopia (1976)

“Patti was great, just an amazing person and a fabulous songwriter. Having co-produced Allen Ginsberg with Bob Dylan, and through my work with Yoko Ono, Patti’s people felt that I could handle somebody who dealt in spoken-word songs.

“This is one of Patti’s favorites. The idea was, ‘What’s the limit? How far can we go?’ We wanted to make a piece of art, even though Clive Davis was saying, ‘Where the single?’ But we didn’t want to fall into that kind of thinking.

“Patti played guitar on the title tune, which is something that nobody else would let her do. She had a Duo-Sonic that was really cool, and she loved to get crazy sounds out of it. We tried the song about four or five times, but we weren’t 100 percent happy with it.

“One night, there was a hurricane, and I told her, ‘Do not go out tonight.’ But a little while later she called me and said, ‘I feel it’s tonight.’ So I drove out in this horrible rain and storm, and we got everybody there, and at about three in the morning, we got it. The track was there, and it sounded terrific. She was feeling it that night.”

Cheap Trick - Cheap Trick (1977)

“I was visiting family in Waukesha, Wisconsin, and my brother-in-law said, ‘You have to see this band.’ They were playing the lounge in this bowling alley called the Sunset Bowl. They weren’t signed, and I don't think many people knew about them.

“I was a little unsure, but I went to see them, and I was floored. I couldn’t believe it. They were so good – everything about them was tremendous. I told them that night, ‘I’m going to get you guys a deal. We’re going to do this.’

“I called up Tom Werman at Epic, and I said that I had something really special. ‘If you don’t get here by tomorrow night,’ I’m going to take them to RCA,’ I told him. He flew out, and he fell in love with them too. He offered them a deal, and within a month we were in pre-production.

“I wanted to capture what I heard live. I wanted it to be raw, straight-up and true to what the band was. We did it really fast. There was no reason to mess with what they were. The only thing was, by the time they did the second record, I was doing Draw The Line with Aerosmith, which took a year, so Tom ended up producing them on a few albums.”

Cheap Trick - At Budokan (1979)

“I got a call from Rick Nielsen, who told me, ‘We were really surprised by the response we got in Japan. It was like we were The Beatles.’ He asked me to fix up these live tapes and turn them into something that could be released for the Japanese market. At the time, nobody was thinking beyond that.

“I said, ‘Sure. Bring in the tapes, and [engineer] Jay [Messina] and I will take a crack at them.’ But they were terrible! There was no mic on the snare, no mic on the bass drum – the sound just wasn’t good.

“To get a good snare sound, I put it through a speaker that was tied to a snare drum, and we recorded that. So it was Bunny Carlos’ performance, but it was re-created. I did that with the bass drum too. The guitars and vocals were great, but I did some re-amping. That’s how we got it – and it turned out to be their biggest record.”

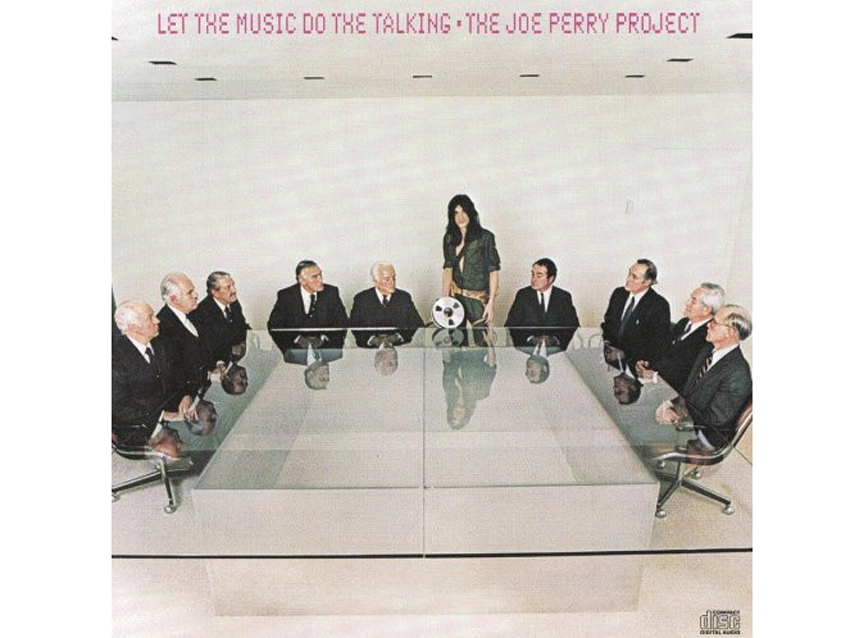

The Joe Perry Project - Let The Music Do The Talking (1980)

“I like the record a lot. Starting with Draw The Line, drugs had really driven the band apart. It was too much, the band was too young, and they were too naïve. Joe had a lot that he wanted to express, and so he left the band.

“He had a lot of strong material, but he made it very clear to everybody that this was his show. He had ‘lead singer disease,’ and he told Ralph [Morman], the singer, ‘Here’s the line. I’m out in front, and you don’t go past this line.' So he had both ‘lead singer disease’ and ‘lead guitarist disease.’

“It’s a terrific album, though. Joe had all of this pent-up music, and the playing was just ferocious. It blew out of the speakers.”

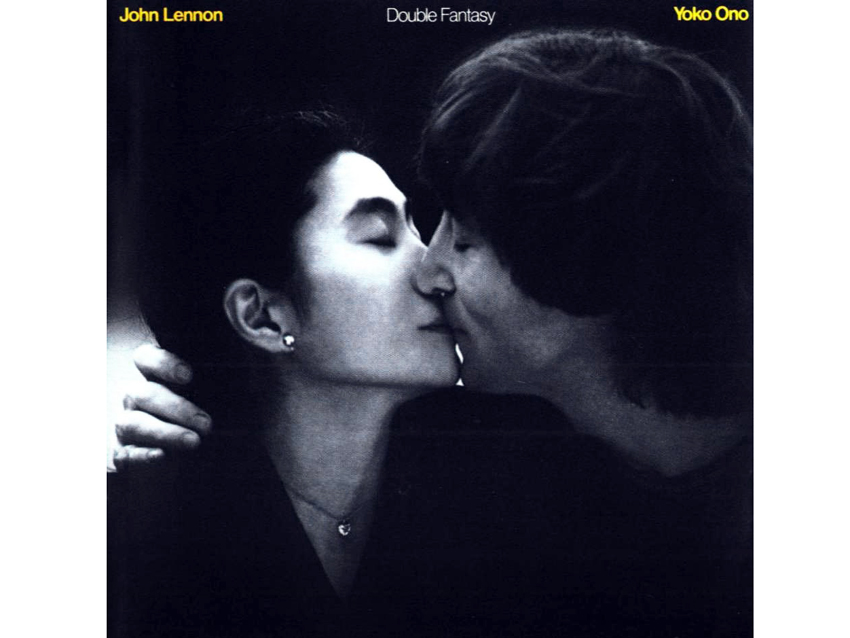

John Lennon & Yoko Ono - Double Fantasy (1980)

“I had run into John a year before we did the record. It had been a while since we’d seen each other. He was so nice, congratulating me on being a producer and everything. He told me that he had been making bread and basically being a homebody. He was very happy. He had Sean with him, who was probably four at the time. It was so great. Then he gave me his private number and said, ‘Call me up. Come over to the Dakota, and let’s talk.’ I never did. I just didn’t want to bother him. He had his new life, and I just didn't want to intrude. I thought he was just being kind.

“A year later, I got a strange phone call: ‘If you’re interested in doing something with John and Yoko, go to this pier on 30th Street. A sea plane will pick you up and fly you to an undisclosed location. And you can’t tell anyone what’s going on.’ So I went out there, and the plane came and picked me up and flew me to Cold Springs Harbor.

“ Once there, I went to this mansion, and there was Yoko. She handed me an envelope that read: ‘For Jack’s ears only.’ She told me that John was in Bermuda, had had some things, and if I listened to the tape and liked it, we’d do a record. She also gave me some tapes with her material on it. Then John called for me, and he said, ‘I give you my number, and you don’t call me!’ [Laughs]

“I went home and listened, and I thought, How can I beat this? It was John singing and playing acoustic guitar, banging on some pots and pans. It was so raw and honest. Every song was great.

“The whole thing was top secret. I hired great guys and put together a band, and we did some terrific rehearsal tapes. But they didn’t even know who they were backing – that’s how secretive this was. John didn’t want to come to the sessions at first – he was unsure of himself. So I would record the rehearsals with the band, then I’d go and play them for John, who would sit in his bed at the Dakota and listen to them. He’d suggest some changes, and then I’d go to the band and work things out.

“On the last rehearsal it was finally confirmed to the band who the artist was. This was in another apartment that John had, and he was there for this one. At the door was a Fender Rhodes, and John played me a new song. There was no tape of it yet. It was Starting Over. I heard it and I said, ‘That’s the first song we’ll record.’ I knew it was a hit.

"The whole thing was an incredible experience."

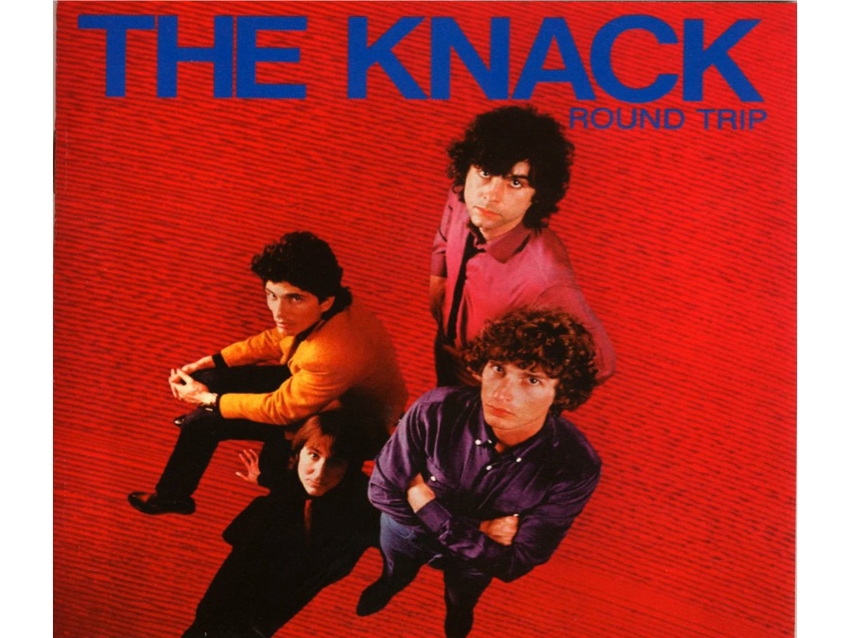

The Knack - Round Trip (1981)

“They were kind of pegged as a particular kind of band. Their record before this one [1980's ...But The Little Girls Understand] got slammed really bad. But Doug Fieger was more influenced by The Doors than The Beatles, and with this album, he wanted to make the kind of record that he always knew he could. I was looking online recently, and I saw something that said Round Trip was considered a classic.

“To be honest, when I first heard My Sharona, it scared me. I studied that record. I thought, Wow, something’s getting past me. I have to really listen to this. But they weren’t interested in making another My Sharona. They had progressed. What they wanted to make was an art record, and they picked me not because I had produced Aerosmith, but because I had worked with Patti Smith.

“The critics and the fans and the people at Capital just blasted us for Round Trip, but we were very happy with it. They were a lot of fun to work with.”

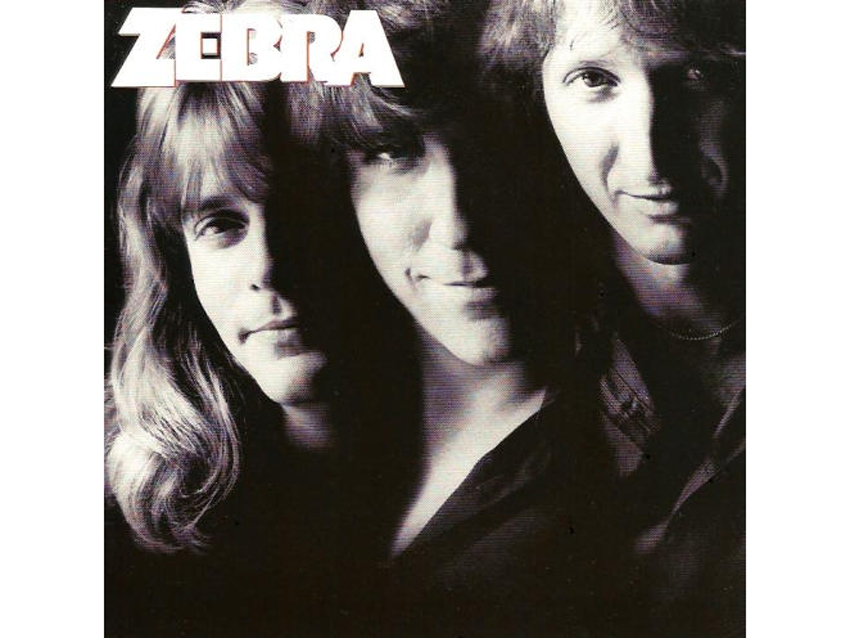

Zebra - Zebra (1983)

“A great record, and it sold like crazy. Who’s Behind The Door? still gets played on the radio today. I went to see them, and I was like, ‘My God, they’re like a Led Zeppelin cover band!’ But they were more than that. Actually, the drummer hated John Bonham, so they weren’t all that influenced by Zeppelin. The singer, Randy Jackson, had a really high voice, and he was super talented.

“Their A&R guy, Jason Flom, had never signed a band before. He’s very successful now, but at the time he was very green. We pretty much guided him through the whole process of getting the band their deal. It was hilarious.

“We worked in great rooms, and it was a blast. It didn’t take very long and it turned out beautifully. A tremendous experience.”

Slash's Snakepit - Ain't Life Grand (2000)

“We cut the tracks at Ocean Way Studios, which was a blast, but Slash kept getting arrested. He used to walk by me in handcuffs with the bail bondsman’s card in his teeth. I would have to take it out of his mouth. He and his girlfriend had this thing going on, and there was always an assault charge being filed. If there was another girl on the same block as Slash, she would go crazy. He’s married to her now, so it all worked out.

“He was so happy to not be working with Axl. I remember Jimmy came down and offered him a million dollars in cash to go back with Axl. Slash told him that even if it were five million in cash, he’d never do it. He really needed a break from that band. He couldn’t stand Axl going on late and the whole thing.

“Slash’s playing was great; the songs were OK. But it was an important step for him as a solo artist. He was very studio-savvy. After we did the tracks at Ocean Way, we went to his studio at his house in Beverly Hills to finish up. He was selling the place, and Billy Bob Thornton and Angelina Jolie came by to took at it. Billy Bob was really interested in the house because of the studio. We had a great time hanging out with them.”

Local H - Here Comes The Zoo (2002)

“Oh, God, I love those guys! They're the original power duo – they were doing it long before anybody else. An absolute blast to work with. I had the second drummer, Brian [St. Clair], and both he and Scott Lucas were spot-on fantastic.

“It has the best ending of any album that I ever worked on. It’s so off-the-wall. You hear the finale, which is all of the songs played at once, and then you have the big stab at the end – ba-daaaaa! These stabs are repeated, with each one coming at an interval twice as long as the one before it. During this, you have these street sounds, and you start listening and getting into what you’re hearing, and then out of nowhere comes another stab – ba-daaaaa! I just love that. I’ve never done anything like it, and I probably never will again.

“I was totally into them. They really do manage to get a big sound out of just the two guys. Some years after them came the White Stripes and the Black Keys, but they’re not half as good as Local H. They led the way. They were the first ones.”

Aerosmith - Honkin' On Bobo (2004)

“I had done a live album with them before this, but Bobo was a lot of fun because it was a blues covers record. Everybody in the band loves the blues, so we had a great time.

“We Johnnie Johnson to come in and play on it. He had been Chuck Berry’s keyboard player. He made it pretty clear that he was doing it for the money, and he did not want to talk to us white boys at all. [Laughs] He just thought we were bullshit white guys trying to play the blues – and moneyed white guys on top of it.

“What Johnnie didn’t know was that I had played bass in Chuck’s band in the ‘60s. There were pictures of me with Chuck, and what we did was, we had one blown up huge. We put it up on the wall so that when Johnnie came in, he’d have to see it. He came in, took a look at it, and when we told him the story that it was me playing with Chuck, well, that broke the ice like you wouldn’t believe. After that, we were fine. Johnnie passed away not too long after that, so we were lucky to get him.

“We threw songs into the hat and really dug in – blues and old rock ‘n’ roll. We did the ultimate version of Louie, Louie with everybody sharing the same amp in Joe Perry’s garage. Guitars and vocals were all plugged into one amp. It sounded hilarious.

“We took the budget for the record and built Pandora’s Box Studio in Massachusetts, but we didn’t get to use it till the end because the fire marshals had their hands out to get the clearances. It turned out to be a great room too.”

New York Dolls - One Day It Will Please Us To Remember Even This (2006)

“Night Bob is a famous New York City soundman. What Bob Gruen is to rock ‘n’ roll photography, Night Bob is to sound. He’s been with the Dolls from the beginning. I was so happy to get a call from him telling me that they were looking to do a record. There wasn’t much of a budget, but I didn’t care.

“We did it at a studio that’s no longer there on 28th Street in New York. Actually, everything we did on that record was on 28th Street. We almost called the album 28th Street.

“David is a genius. We’ve always kept in touch. I’m such a fan of his. And the rest of the guys were a joy. Not everybody in the band from the old days was there. Johnny Thunders – I used to go seem him and wonder if he would make it through the show. One day he didn’t.

“The record is so interesting, and the lyrics are amazing. I listen to it over and over, and I’m still finding new meaning in the words. They’re so literate. I have to get a dictionary out to follow it. And the album has the last recorded performance by Bo Diddley. That’s pretty cool.”

Michael Monroe - Sensory Overdrive (2011)

“This was Michael making a comeback. He hadn’t done anything in a while. There was no budget on this record, none at all. But he had a great band, great demos, and I agreed to do it for the kind of money that might get you a couple of hot dogs.

“I liked Michael a lot. I even lived with him while we were making the record at Swing House Studios in LA. I figured out a way to make it happen. He has a great work ethic, a fantastic attitude, and I totally believed in him. Five days of pre-production and not a lot of time recording.

“I got Michael to play sax on the record so he could go out and do it live again. He’s a fantastic sax player. I’m so glad I did the record. The challenge is worth it sometimes. It can’t be about the money. It’s hard to enjoy every minute of making an album, but somebody in the band always stepped up and made it worthwhile.

“It won Album Of The Year from Classic Rock magazine, and it went gold and platinum all over Europe. Of course, it did nothing in the States.”

Aerosmith - Music From Another Dimension! (2012)

“There wasn’t a lot of pressure in the studio. The only real pressure was getting everybody in the room and getting the car started. Once you do that, you can pretty much put it in ‘drive’ and it goes. This was a creaky car at first.

“I wasn’t the first producer to take a crack at getting them going – four other guys were in there before me. I think it just became a matter of ‘We can’t bullshit Jack. There’s no way he’s going to fall for it.’ I know Brendan O’Brien was like, ‘These guys are impossible.’ I can understand that, but to me, it’s a little bump in the road.

“As soon as we got past all the minor crap that was in the way, it started to get fun. We established a flow, got early morning starts – once you get into it, it takes off. We had meetings in my office, we listened to little gems of songs – it was just like the old days. And the important thing was to take a song and get it recorded right away, with everybody on the floor all at once.

“The idea of the record was to show the history of the band, every aspect, which is why it’s such a big album. To do that, you need people writing in different groups and material coming from all directions; you need Diane Warren. I did a lot of writing too, and I always have. To me, that’s just part of making a record.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues