Production legend Eddie Kramer talks about 11 career-defining albums

For millions of guitarists, hearing Are You Experienced by The Jimi Hendrix Experience and Led Zeppelin II were life-changing events. Producer and engineer Eddie Kramer remembers both records well but for his own wholly unique reasons: He was present during their creation, working closely with Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page to realize their visions on what would become two of rock's most celebrated and iconic albums.

"I don’t think we realized for some years later how impactful it all was," Kramer says. "When you’re doing the work, that’s all you’re focused on – getting things done, getting them right. All that I wanted to do was satisfy the clients and not make a fool of myself. I wanted to get the best sounds that I could. It wasn’t until the mid-‘70s that I looked back at what we’d done in the ‘60s and thought, ‘Hey, that was pretty interesting.’"

Born and raised in Cape Town, South Africa, Kramer studied classical piano at the prestigious South African College Of Music. Gradually, his interest turned to jazz, followed by rock 'n' roll. "And then the rot set in," he says with a laugh. "It was a downward spiral from that point. This caused some sadness for my father, who wanted me to be a concert pianist." Kramer pauses, then adds with a chuckle, "Once he met Jimi Hendrix, he changed his mind."

In 1961, at the age of 19, Kramer moved to England, where he embarked on his recording career, taping local jazz groups before getting a job at Advision Studios in 1962. In short order, he moved over to Pye Studios, where he learned the ropes from chief engineer Bob Auger. "He was an absolute genius," Kramer recalls. "A very important mentor."

In addition to Auger, Kramer credits Keith Grant from Olympic Sound Studios (Kramer joined the facility's team in 1966 and worked on recordings by The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, among others) and producer Jimmy Miller with teaching him the ins and outs of recording. "I was fortunate in that I had three really good mentors," he says. "The gradual process of learning the craft under these great engineers really focused my attention on what I was supposed to be doing. I think the whole concept of being an apprentice, so to speak, or a tea boy, under a mentor has great merit."

These days, many aspiring music makers are capable of creating sophisticated recordings on their laptops. While Kramer admits that quality work can be done with Pro Tools and home setups, he firmly believes that something important is being lost in the process.

"Having musicians in a room looking at each other eyeball to eyeball, grinding it out, fighting over it – it’s vital to making good music," he says. "The concept of somebody on their own with their laptop and headphones is such a selfish procedure. To me, it should be a communicative effort, and that’s how you get the raw feeling of musicians interacting with one another. That’s the glory of a great production.”

A triple-threat record maker, operating as producer, engineer and mixer (and even songwriter, so he's a quadruple-threat), Kramer has, over the years, put his sonic imprint on a staggering number of classics – in addition to Jimi Hendrix and Zeppelin, he's helped shape landmark releases that run the gamut from AM pop to stadium rock to thrash metal crunch. On the following pages, he looks back on 11 of his most notable recordings.

Currently, Kramer is involved in a number of projects, such as a long-planned memoir, From The Other Side Of The Glass. He's also worked on the development of the DTS Headphone: X, which he describes as "essentially an app that has been created so that with any pair of headphones in any source will get you exact replication of speakers. It’s the scariest and most wonderful thing you have ever heard.”

Kramer is also set to launch a new line of wireless F-Pedals at the upcoming NAMM in January 2014. "I'm very lucky to have paired with my friend Francesco Sondelli," he says. "Francesco is very imaginative and worked very, very hard on these pedals. It’s got some technology that nobody’s ever done before.”

In addition, he's just wrapped an EP with the Memphis-based band American Fiction, set for release in January, and will soon be working with 13-year-old blues guitar phenom Ray Goren. For more on Eddie Kramer, visit his official website and Eddie Kramer Archives.

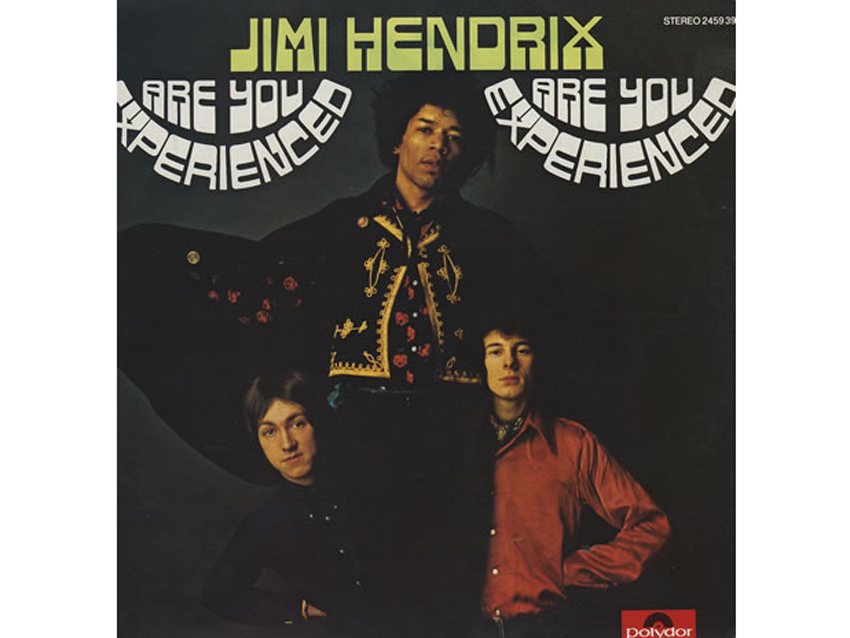

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Are You Experienced (1967)

“I was at Olympic in the early stages of the new studio, which was phenomenal and very cutting edge. I was a junior engineer, and I got a call from the studio manager who said that I should be recording Jimi Hendrix. That’s how I got the gig.

“When Chas Chandler discovered Jimi in America and brought him to England, he wasn’t writing as Jimi Hendrix from a song point of view. When they did their first show in Paris, at the Paris Olympia, they were doing cover songs. By the end of ’66, Jimi had already written three or four songs, and by the time I got to him he was off to the races, writing a tremendous amount.

“I started working with Jimi in the middle of January ’67, and we began putting the album together. He already had the single Hey Joe, and The Wind Cries Mary had been cut – three or four things were cut, actually. On those songs, we did overdubs, and then we cut a bunch of new songs, which, of course, was the album. I mixed the record at Olympic.

“Chas’ contribution was as a producer, helping Jimi write the songs and making sure that everything was recorded in an efficient manner. He came from the old school of the three-minute song. Jimi’s job was to come up with the goods in terms of the crazy sounds, which he did with the use of his pedals and his amazing playing.

“I took what Jimi was doing and tweaked it out and pushed the envelope from an audio perspective. That was the basis of our relationship, the fact that we both enjoyed each other’s creativity. The challenge of recording Jimi was immense, but the fact that he appreciated my adventuresome ways with sounds cemented our relationship.”

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Electric Ladyland (1968)

“This is the record that started to change the direction for Jimi. We started it in 1968, when I first arrived in America. Very soon thereafter, Chas Chandler decided to part company with Jimi because he felt that Jimi wasn’t performing for him or the album – he was bringing in all of his buddies and friends and hangers-on from the Scene Club. There were 15 or 20 people in the control room, all of them Jimi’s friends.

“It was left to Jimi and I to finish the record, which was great because Jimi had the freedom to do what he wanted. It was a double album, and we were able to experiment and really stretch the boundaries. There are tracks that are jazzy, some that are R&Bish, some that are ethereal and experimental.

"On the song 1983, we tricked the thing out with every conceivable effect that I could think of. The way that track was mixed was Jimi and me doing a performance mix. It was all one take. We rehearsed it a couple of times, but essentially that whole song was mixed as one pass with no edits. It was the two of us at the board, four hands on deck. He had a lot of sensitivity, and he could mix. We worked very well together. We were a team.

“He loved Bob Dylan. We cut All Along The Watchtower in London before I left for New York, with Dave Mason and Jimi on acoustic guitars, and Mitch on drums. No Noel – Noel didn’t play bass because Jimi said that he was gonna do it. Noel got really pissed and went to the pub to get drunk. So Jimi played bass on it, and we brought the tapes to New York and continued working on it. That recording of Watchtower has become the de facto performance and arrangement of it. Today, Bob Dylan plays that arrangement.

“Jimi was so fun and funny in the studio, cracking jokes all the time. He was focused, but very relaxed. He had a sound in mind, a direction in mind, and I was just helping him realize his dream. Did I help change the sounds? Yes, of course. Did I make it more exciting for him? I’m hoping that he felt I did, which is why we continued to work together. He had a far-reaching vision, beyond most human beings. Trying to keep up with him was a challenge.”

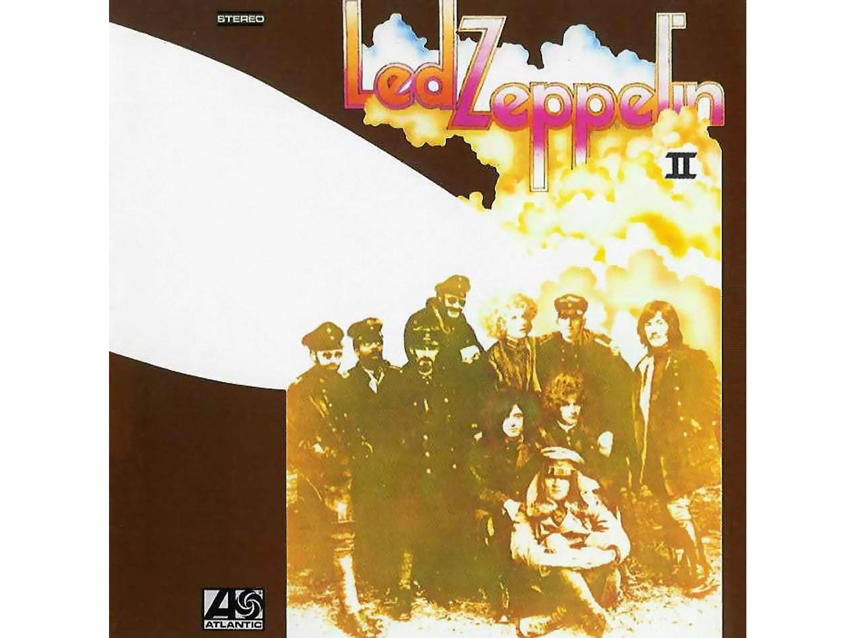

Led Zeppelin - Led Zeppelin II (1969)

“I knew Jimmy and John Paul as session musicians from Olympic. And then, of course, they had did done their first album Zeppelin album and were successful. They’d started doing some tracks for Led Zeppelin II, and they were all over the place – some things were done in London, some were on the road; they had this huge trunk of tapes. I got a phone call from their office in New York: ‘The boys are in town, and they want to know if you want to help put this record together.’

“We went in the studio and cut a whole bunch of tracks. We did a lot of overdubs, including on some of the existing tracks they had. We mixed the whole thing in two days at A&R Studios in New York. That was nothing in those days – I mixed Are You Experienced in one day.

“Jimmy Page was very demanding. I use the comparison to Jimi Hendrix – both very demanding, very clever and on top of their game. They knew what they wanted to hear. Page even more so – because of his experience as a session musician, he was directing everything. This was his deal; he was the creator of the whole concept.

“That’s not to say he could have done it without the other musicians. Having the best drummer in the world and probably the world’s greatest rock bass player – one who was also a superb arranger and a master of many, many talents, like keyboards – that was key. You couldn’t imagine Led Zeppelin without the component parts; each component made the whole. And Robert Plant – you couldn’t put together a better rock dynasty than Zeppelin.

“The echo in Whole Lotta Love was a mistake – it was one of the biggest mistakes I ever made. We were in the middle of the song, and it comes to the break – ‘Woman…’ And you hear another one – well, one of the other vocal tracks was breaking through because we were using this funky old console. It wouldn’t allow me to turn the vocal off; I couldn’t get rid of it. Page and I looked at each other at the same time, and we grabbed a knob and threw a shitoad of reverb on it. We laughed and said, ‘Let’s leave it.’

“That is a classic example of leaving the damn mistakes in, because you never know where it’s going to lead you. It was a mistake; it wasn’t supposed to be there. But because of Page’s creativity and my being on the same page as him – no pun intended; I can’t believe I just said that! – it’s now part of rock history. I tell this in my lectures to audio students: ‘Leave the damn mistakes in.’ People with Pro Tools are using it as a weapon to kill all bloody creativity. Let it all hang out and be hairy.”

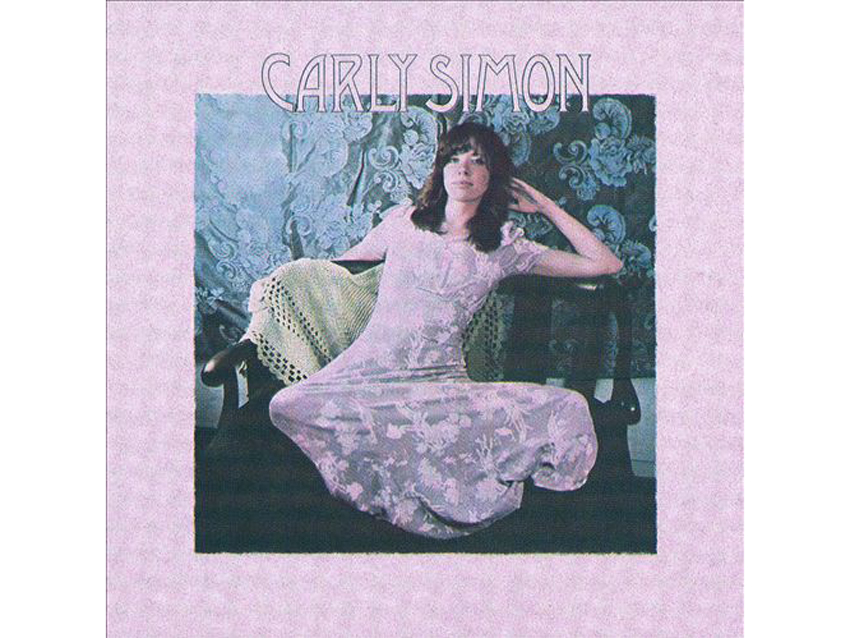

Carly Simon - Carly Simon (1971)

“I had done some stuff with Carly’s manager, Jerry Brandt. He brought her to me at Electric Lady, and we started working together in 1970. Right in the middle of it, Jimi died, and that was a very traumatic and earth-shaking moment. I had been trying to finish a record with him – he went to England in August of 1970 – and so it was a very tough time for me.

“But working with Carly was a marvelous experience. I actually co-wrote a couple of songs on the album. She’s very creative and adventuresome and is a great songwriter. You have to remember, in those days, women weren’t really making their own records, and so this was an important collaboration between us. We pulled our resources and brought in the best musicians to support her. We had great support from Jac Holzman at Elektra. He was the guy, an executive who had his finger on the pulse of what was going on. He really respected Carly and knew she was a great songwriter.

“She had the single, That’s The Way I Always Heard It Should Be, which took off and did incredibly well. She would write on the piano or on the acoustic guitar – and she had great co-writers. She would present the songs as a fait accompli in the studio – they were done. It was just a matter of the musicians rehearsing them a couple of times, and we were there. Carly had a good sense of what she wanted to hear. In this early, formative stage for me as a producer, not having that much experience at it, this was a trial-by-fire experience for me, too.

“We would cut stuff quickly; in an evening, we’d do three or four songs. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. It’s not rocket science. It’s a really good-sounding record, and I think it speaks for itself. It’s the record that broke Carly into the commercial market, and I also think that it set the tone for a lot of female singer-songwriters.”

NRBQ - Scraps (1972)

“I started working with them in 1968 at the Record Plant. I did their first album there. This was the early band, when they were on CBS. They had Steve Ferguson, an absolutely amazing guitarist – mad as a hatter but a phenomenal guitar player. Jimi Hendrix used to go and listen to them jam at the Scene Club. They were the hot young band in New York.

“We did the record in their house in Oneonta, New York, using a 16-track mobile recording truck. I had a very nice console, a good tape machine and a bunch of mics – this was the Fedco truck that I used to record many shows at the Fillmore East. I figured, ‘OK, they have their thing in Oneonta. We’ll just drive the truck up and record it there.’

“The band was a bunch of brilliant musicians. Terry Adams, the keyboard player, played rock ‘n’ roll on the piano that was a combination of Thelonious Monk and funky blues from the ‘50s. The guy was an absolute genius. And the rhythm section was phenomenal. Joey Spampinato on bass – unbelievable.

“They could be very unpredictable, and that was a thorn in the side of the record label. The band could never figure out where they were going with their next song or next record. They were definitely unique.”

Led Zeppelin - Houses Of The Holy (1973)

“Houses Of The Holy and Physical Graffiti are sort of interconnected, so I’m involved with both records to a degree. There were a bunch of engineers on both records, actually. We cut tracks at Stargroves, which was Mick Jagger’s house, using the Stones’ mobile. So we had all of these tracks, and Pagey would figure out what he wanted to do with them. That was his vibe.

“This was one of the most exciting things I’d ever done in a truck. The acoustics in Stargroves were great. We put John Bonham in his own room in the conservatory, Page’s amp was in a fireplace – all kinds of crazy shit we would get up to.

“Once again, working with Page and the boys was just wonderful; they were creative as all hell. We were isolated in the sense that we weren’t working in a studio, and Pagey liked that a lot. He’d used Hedley Grange, and Stargroves was a very good substitute. I really liked the room we had for Bonzo – when you hear the sound of the snare on D’yer Mak’er and Dancing Days, it just takes your head off.

“With D’yer Mak’er, they’re playing Jamaican rock. It’s amazing, and they really got the feel of it. This is a tribute to the fact that the rhythm section could play anything. It didn’t matter. If Pagey had an idea for a very strange rhythmic pattern, he would show Bonzo how to do it, and once Bonzo locked into it he’d be off to the races; not tempo-wise, but being very creative to the beat that was given to him.”

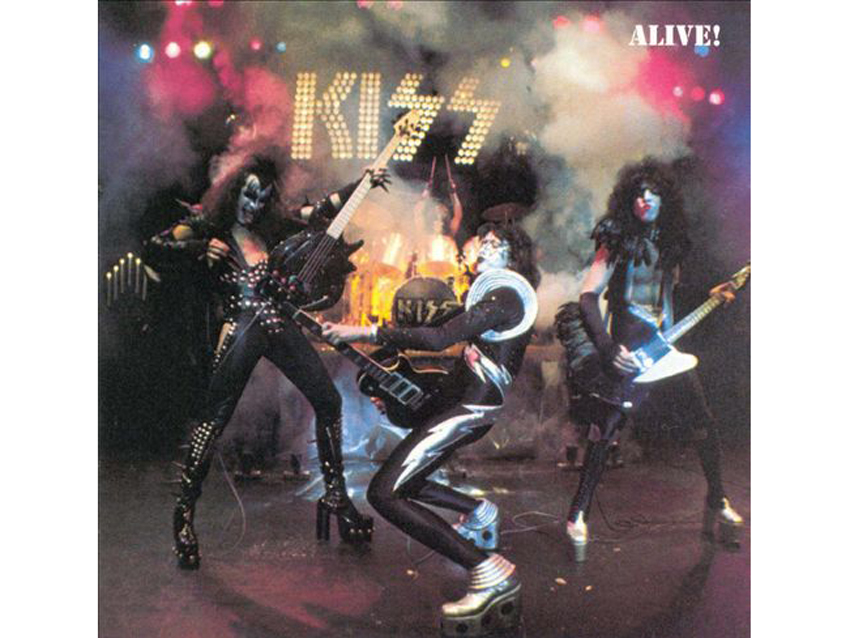

KISS - Alive! (1975)

“I had done their demo, the one that got them a deal, at Electric Lady in 1973. We did it four-track in Studio B in one day. I didn’t work with them on their first two records. The record company, in their infinite wisdom, wanted somebody who could give them some hits. I don’t know about that… but it certainly established the band.

“They went on the road and toured behind those albums, and they built up a terrific fan base. When it came time to do the live album, Neil Bogart, the head of Casablanca, called me up and asked me if I wanted to do it. I said sure. I thought it would be a challenge – they’re jumping around in their high boots, smoke bombs and explosions, all kinds of crap going off. I said, ‘It sounds like fun.’

“And it would be a challenge: It was very tough to get the band, in that kind of atmosphere, to play in time and in tune. That was the hard part – to capture enough performances where it was really good. I think we got the live essence by virtue of the multiple gigs they did. There was one in Cleveland, in Detroit, in Iowa and another one in Wildwood, New Jersey.

“Wildwood was where the rubber met the road. We used the same Fedco truck that I recorded NRBQ with. It was interesting trying to record the band in a 1,200-seater club with no PA system initially, till the crew went out and stole a scaffolding from a local building site in order to build a platform for the PA. This was in the afternoon right before the gig.

“The band was amazing. Gene and Paul were the driving force behind the organization and for what was supposed to be on the record. We worked pretty closely together on that. Ace – I love him. A fantastic guitar player, vastly underrated. I think the whole band played great. Again, it was a challenge to get the best bits. We did a lot of overdubs to make it sound right. But in the end, they saved Casablanca’s asses – the label was going under. Between KISS and Donna Summer, they saved Casablanca.”

Peter Frampton - Frampton Comes Alive! (1976)

“Peter had a tremendous catalogue of great songs, and he had a very aggressive manager, Dee Anthony. If you trace Peter's career, it’s a very good one in the sense of the experience he had with The Herd and then Humble Pie. I’d done a couple of albums with him – they didn’t sell too well, but the songs were fabulous.

“What he was doing was laying the groundwork, much like KISS did. KISS toured behind their first records, and so did Peter. He started to figure out, ‘Hey, this could really work.’ That’s what’s missing today: Bands don’t have the chance to fail. Not that Peter failed, but he had the chance to play the shitty gigs and figure out what the audience wanted.

“The band was great. Working in the studio with Peter, prior to the live album, I found him a drummer named John Siomos. John was phenomenal – he had played on the Carly Simon record, and that’s when I recommended him to Peter. That was the foundation right there. And, of course, he had the best bass player [Stanley Sheldon] and the best keyboard player [Bob Mayo]. It takes time to find musicians who really click with you, and these guys clicked.

“I recorded it with the truck again. The stuff sounded great, but did I know it was a hit? No – you never know. If I could predict what the public was going to want, I’d be an incredibly wealthy man today.”

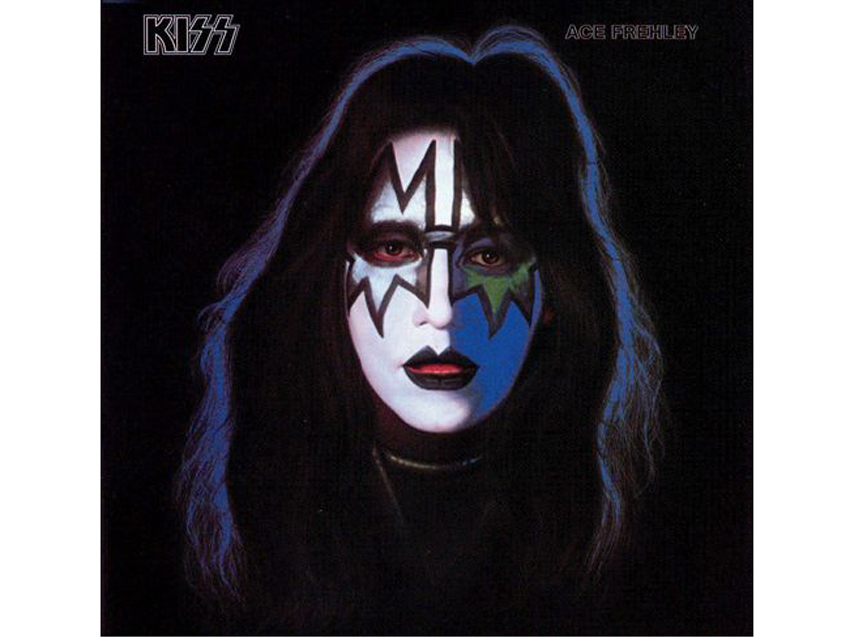

Ace Frehley - Ace Frehley (1978)

“The band wanted to do solo albums. The other guys went off and did their thing, and Ace came to me because he knew I could get him a great guitar tone. We worked very well together; it’s similar to the kind of relationship with the Zep guys or Jimi. I was always empathetic towards his abilities, and I loved his playing. I figured we could make a good record.

“There were no shenanigans. Ace knew that if he could make a statement on this album he would be proving a point, and he really set out to prove a point. He was fortunate in that we picked the song New York Groove, which I thought was really great. He sang his ass off on that and worked hard. He was creative, he was inventive, and he was very focused.

“We had a brilliant rhythm section, Anton Fig and Will Lee. It doesn’t get much better than that. It just clicked. We were up in this huge Colgate mansion in Connecticut – I did the old mansion trick one more time with another truck. We got great guitar sounds, great drum sounds. It was a good atmosphere with a band working together as one unit.

"Ace was very nervous about singing, and he felt quite insecure about standing up and singing. In order to make him comfortable, we set up a studio in a very particular way. We put down a little rug and turned all the lights down. Ace would lie down on the rug, with a bottle of beer in one hand and a microphone on his chest, and that’s how he started to sing. By the second song he was sitting up, and by the third song he was standing up.

“Much to the chagrin of the rest of the band, he had the best-selling album – it sold a million copies, I think. The others didn’t do quite as well.”

Fastway - Fastway (1983)

“Fast Eddie Clark was great. A fantastic guitar player. But Dave King, the young singer – wow! Boy, what a bloody voice he had. The band was very good, but to me, the combination of Eddie’s guitar playing and Dave’s voice was the key.

“A radio station in Cleveland picked up on the record. I remember that’s how it happened back then: A regional FM station could break a record. Somebody would call the head guy at CBS and go, ‘Hey, we got this thing happening here,’ and then bam! They’d put money into it. That's how things worked in those days.”

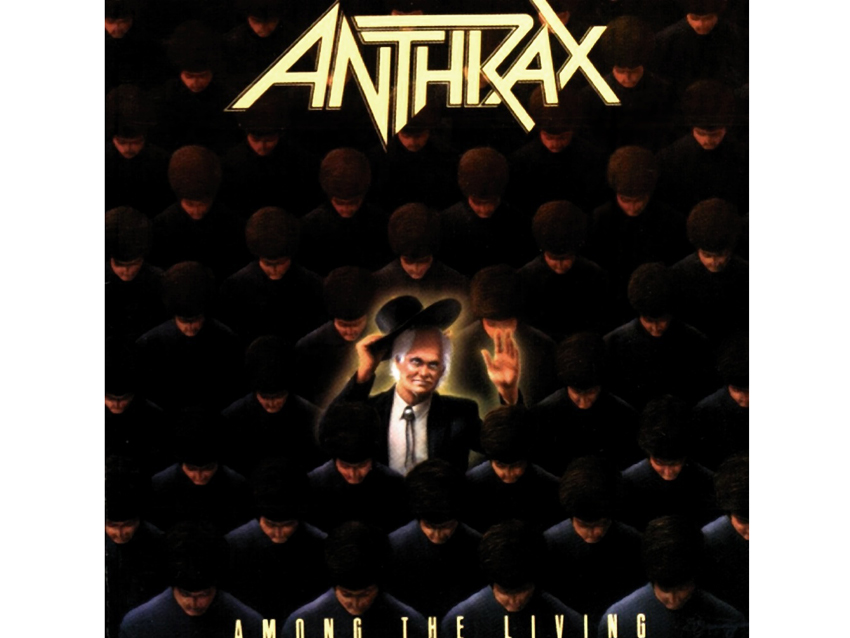

Anthrax - Among The Living (1987)

“Their manager, Johnny Z, said to me, ‘I’ve got this band, Anthrax. They like the sounds you get – would you like to work with them?’ That’s what started it. We went to Florida and took over a small studio for about a month. We also went down to Chris Blackwell’s studio, Compass Point, in the Bahamas, and did some work there.

“It was a tough record for me; I’d never recorded anything quite like it. I wasn’t sure of what they were looking for initially. And it was a challenge to figure out ways to record heavy guitars with heavy drums – it was just a different process. The guys had a totally different attitude, a totally different way of thinking, and I remember it being contentious during the mixing. As I said, it took me a while to figure out what they were looking for, but once I did, it all turned out incredibly well.

“One of the bizarre things about the record: There’s a song called I’m The Man [issued on an EP of the same name], and that became a hit in Europe. That was the one song where everybody switched instruments. I even played piano on it. It was a joke – we did it as a giggle. Somebody picked up on it, and I think it went Top 10 in the UK. Again, you can never predict what the public is going to want.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.