Production legend Dave Jerden on 13 career-defining records

"I never made records for the audience. I only tried to please one person – me."

Production legend Dave Jerden on 13 career-defining records

PRODUCTION EXPO 2013: If you want to get on Dave Jerden’s bad side, try calling him a producer and see what happens. “Makes me sound like a dilettante,” he snorts. “That might be fine for some people, but not me. I just don’t like the word. I don't like the way it sounds."

So what would he prefer to be called? “An engineer is fine,” he says. "See, my father was a musician, so I used to go to sessions with him. I watched the engineer, and I thought he was the most important guy in the room. He was the guy making the record, not the producer. The engineer was always working, he knew what all the knobs and equipment did – he was like a rocket scientist."

In the late '70s, Jerden learned what all the knobs did as house engineer at Hollywood's famed Eldorado Studios, which served as his home base until 1996. It was an environment and a role that suited him. "I was centered," he says. "I knew who I was, and I got the job done." But by the mid-'80s, after he finished work on The Rolling Stones' near-breakup album Dirty Work, Jerden's world began to change. "My manager told me there were some new artists who wanted somebody different to produce them," he explains. "I guess it was my time. But I really started producing out of default. It's not what I was looking to do."

He didn't do too badly, though, especially with a pair of unruly late '80s bands – Jane's Addiction and Alice In Chains – who kicked up calamities of fresh, unrestrained sounds that helped flush the preconceived notions of the day's reigning hair metal bands right down the toilet. “My forte was bringing alternative bands into the mainstream," Jerden says. "Groups that were relegated to smaller labels and got attention in fanzines were the kinds of things that I gravitated towards. I treaded on the bits that other people missed, and they missed some good stuff.”

By the mid-'90s, Jerden was swimming in cash, driving a Porsche, and owning not one, not two, but four homes – and he was miserable. "For years I drove an old pickup truck and lived in small places, but I was happy," he says. "When you have a boat and six horses and all this stuff, you have to keep generating income to pay for it. I’m not that kind of guy. So when I found myself making corporate-type records and feeding the radio machine, I realized that I lost my bearings. I wasn't making records for the right reasons anymore."

He didn't retire, but he did lie low, working occasionally during the '00s while spending a lot time studying the applications of digital to analogue and experimenting with new ways to record. “It’s only recently that I decided to really get back in and do some work again," Jerden says. "There’s still new avenues to explore, new ways to make good records fast, so it’s exciting. If people have talent and have something to say, and if they want to work with somebody with a lot of experience, I’m interested.”

On the following pages, Jerden looks back at 13 of his most notable recordings, whether he was engineer, mixer or, ahem, producer.

Talking Heads - Remain In Light (1980)

“We did this record after Bush Of Ghosts, but it came out first. A couple of months after I finished with Brian Eno and David Byrne, I call a call from Brian in the Bahamas asking me if I could join him and the Talking Heads.

“I went down and finished off the time they had booked, and then we went to New York and continued. It kind of felt like an extension of what we did on Bush Of Ghosts. The rest of the Talking Heads were terrific musicians and a great bunch to be around. Jerry Harrison had amazing ideas and was a very versatile player. Chris Frantz was rock solid, just like a heartbeat, and a great guy, too. And Tina was a fantastic bass player, right on the ball, really professional. Sweet people.

“There was a lot of experimentation, laying down track after track, throwing stuff away, editing stuff – constant work but fun work. You never think that this stuff is going to be so received so well. I remember when it came out, I was at a party in LA and all of these people were talking about it. It was really catching on with everybody. Robbie Robertson introduced me to Peter Gabriel, who told me that he loved the record and that it really influenced him. Pretty cool.”

Brian Eno-David Byrne - My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts (1981)

“I did this at Eldorado. It's funny because I actually lied at the time: I put an ad in the paper and said that we had a Lexicon 224 digital reverb, which we didn’t. I got a call from somebody who said that Brian Eno wanted to come by and see the unit, and so I had to call some folks at Village Recorders to borrow one of theirs, which we eventually ended up buying.

“Brian came over, and I showed him the machine. He had a bunch of tapes with him, which was the beginning of the album. He played me some of the stuff, asked me what I thought, and I told him I thought it was great. He left, and then Nadia, the studio manager, told me that Brian had booked nine weeks with us.

“At this point, I’d been recording for about three years. David Byrne and Brian Eno opened my eyes up to the creative process. Those two guys were so musical and intelligent. I had so much fun with them – it was probably the happiest time in my life.

“The equipment was pretty rudimentary – there was no MIDI – so all of the loops were made by hand. We’d record 24 tracks and mix them down to two tracks, make a loop of that and then put that onto two tracks of another 24 track. We just kept going like that.

“The two of them were fountains of ideas. Being around them was unlike anything I’d ever experienced before. I was really excited to be working with them, and I think my enthusiasm was inspiring to them. They had worked with other people who used to get bored, so I was kind of a change of pace.”

Red Hot Chili Peppers - The Red Hot Chili Peppers (1984)

“I’d seen the band playing in town before they got signed, and I thought they were great. Steve Moir at MCA Records suggested that I get involved. I met with Andy Gill from the Gang Of Four, who was producing the record, and after that I was hired.

“Andy was cool. He was a very nice English gentleman, and of course, he was a brilliant guitar player. I loved Gang Of Four – I even paid money to see them. Flea and Anthony Kiedis fought with Andy a bit. I think they thought that’s what bands were supposed to do, fight with their producer. I was kind of a stabilizing force on the record.

“I only mixed a few songs on the record. What happened was, Andy got sick. He developed cancer and had to have an operation. At that point, I bowed out. The band wanted me to continue, but I just didn’t want to do it without Andy. All of the producers I worked with, especially the ones I really liked, I felt a real allegiance to them. I felt like I was their second mate and that I should have their backs.

“It’s a really good record. The Chili Peppers were the best band in LA at the time. Everybody thought they were going to be a smash right away, but it took them a long time for them to catch on. I don’t think the world was ready for them at first.”

Herbie Hancock - Future Shock (1983)

“I had done some work on a record of Herbie’s called Lite Me Up, and I remember one of the record company folks saying something like, ‘If this record doesn’t go double platinum, we’re gonna hang up a For Sale sign in front of Columbia.’” So, of course, the record did nothing.

“Herbie had run out of money, and so I was hired to go over to his garage where he was making this record with Bill Laswell and Michael Beinhorn producing. Total shoestring. I came in and worked on something like half of the record, but I did mix the whole thing.

“Sampling was just starting to happen. I had an AMS sampler, and I used that on a lot of the record. Herbie spent a lot of time messing with synthesizers, so my job became to just help him get everything done and to set up a mood. I kept things moving along.

“Herbie was going to try to sing on the song Rockit, like he had done on Lite Me Up, but in the end he didn't. I remember Michael Beinhorn saying, ‘C’mon, rock it, Herbie!’ That’s where the title came from. The same guys who said that Lite Me Up had to go double platinum came in to hear Future Shock. One of them said, ‘There’s no vocals,’ and they started talking about the idea of putting some singing on the album. At that point, Bill Laswell got up and said, ‘Fuck you, I've got a plane to catch.’ And he walked out. He knew the record was great, and of course, it was. It became a big hit.”

Mick Jagger - She's The Boss (1985)

“I got a call from my mother, who said that this nice English boy had called up. She said his name was ‘Mick something or other.’ I said, ‘Mick Jagger?’ And she goes, ‘That’s right, Mick Jagger. I talked to him for quite a while – he’s trying to get a hold of you.’ Mick had liked Future Shock, and he wanted to contact me. He looked in the phone book, and as it so happened, my mother was the only Jerden in LA who was listed.

“I went down to the Bahamas where Mick was working. He had Jeff Beck, Jan Hammer, Michael Shrieve, Tom Petersson from Cheap Trick – all of these people were working on stuff with him. The idea was that I would engineer and Bill Laswell would produce. There was no grand plan to anything. It didn’t start out to be a Mick Jagger solo record, but Walter Yetnikoff pushed him into it, which would soon cause some real problems between Mick and Keith.

“Mick was great, and he was very good to me. He gave me carte blanche to do whatever I wanted on the record. I remember I was working with Jeff Beck on a guitar solo, and he had a bit of a problem coming out of the end of this particular part, so I was comping the ending. Jeff asked me what I was doing, and when I told him, he said, ‘Well, you’re playing my solo!’ Mick stepped in and went, ‘Oh, leave him alone. He knows what he’s doing.’ That’s the way Mick was. He always backed me up.

“Mick played a lot of records for us. ‘I’m into this, I’m into this, I’m into this,’ he would say – a lot of it was dance stuff. He wanted to have fun and play around with things that were outside of the Stones structure.”

The Rolling Stones - Dirty Work (1986)

“I had worked on She’s The Boss for nine months. I hadn’t even gotten back home to LA yet. I was at a hotel in New York, waiting for a car to take me to the airport, and I got a call from Mick asking me if I wanted to go to Paris to work with the Stones. I had to call my wife and tell her I wasn’t coming home.

“Mick met me at the hotel in Paris, and he took me to the studio. Keith was already there with a bunch of people. He took one look at me and said, ‘I don’t like you. I’m not gonna like you. Fuck you. You’re in the deep end now, motherfucker!’ [Laughs] That was my introduction to the Stones.

“Basically, Keith was pissed at Mick, and he was mad that Mick would bring me into their record. Four days later, though, Keith was hugging me – he liked the guitar tones I got. ‘Welcome aboard, mate,’ he said. After that, he was great to me.

“During the whole record, there was tension between Mick and Keith. They didn’t want to be in the studio together, so Mick would work his hours and Keith would work his hours. After we took a break, Steve Lillywhite came in as producer. He was great to work with, a really cool guy. He was under a lot of pressure, but he handled everything beautifully.

“It was a tough record, and it took a year to make. You had to walk on eggshells sometimes. There was one incident where Keith blew up at me because I’d been hanging out with Mick. Mick wasn’t like that; he wasn’t jealous or anything like that. I really saw their differences while making this record: Keith is the artist. He lives and breathes rock ‘n’ roll and guitars. Mick is more of a businessman. He’s very down to earth, though; he’s not a dilettante.

“Everybody in the Stones organization thought that the band was through. I was like, ‘Oh, great. I wait my whole life to work with The Rolling Stones, and my name will be on the record they broke up over.’”

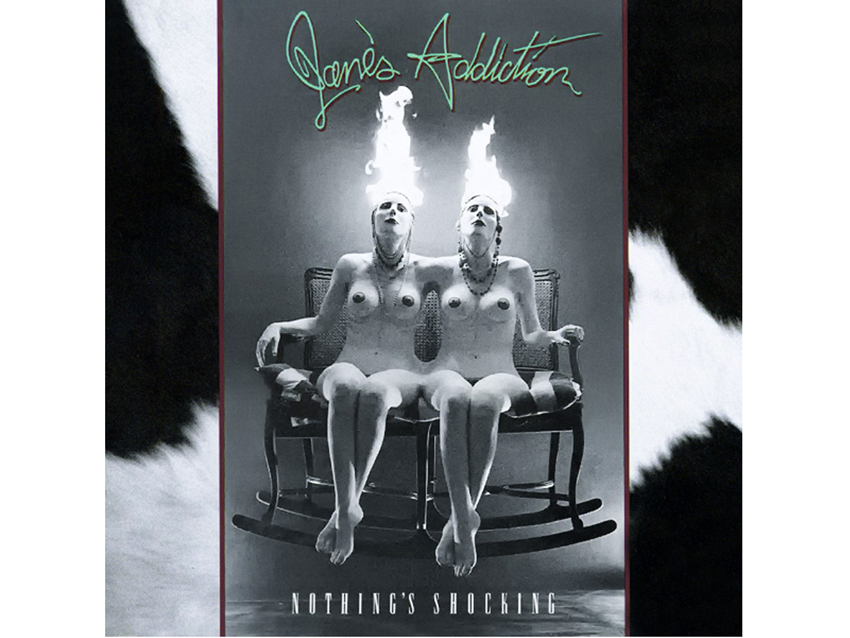

Jane's Addiction - Nothing's Shocking (1988)

“They were the big buzz band in Los Angeles, getting a lot of press. I’d seen them a few times – sometimes they were OK, other times they were great, and sometimes they were just crappy. They were all over the place.

“I went to see them on this one particular night at a club called Scream – it was actually in a hotel ballroom. There was a line of people around the block at 3:30 in the morning. I went in, sat in the back by the soundboard, and let me tell you, Jane’s Addiction took the stage, and they were awesome. I’d seen Jimi Hendrix at the Hollywood Bowl in 1968 – I’ve seen a lot of great concerts – and Jane’s Addiction were as good as Jimi or anybody on that night. They blew my hair back. I told my manager I wanted to work with them.

“They’d talked to a bunch of producers, but I got the gig because I didn’t want to change anything. One producer wanted to make them sound like U2’s Joshua Tree, because that was the big record at the time; another guy wanted to kick Perry out of the band. But after seeing that show at Scream, I didn’t think they needed any kind of ‘fixing.’

“I had a demo tape of 18 songs, and I listened to it every night all summer. I picked nine songs from the tape and put them in an order, and then I said to the band, ‘Let’s do these nine songs. You’ll rehearse them in this order, and we’ll record them in this order.’ And that’s what we did.

“It gave a structure to the band, which was helpful, because I knew that once we got into the studio it could become a bit like Sgt. Pepper, with the band trying everything and getting a bit scattered. I kept things organized, but I still gave them free reign to do what they wanted. Like with Perry’s vocals, I’d say, ‘Just go out and sing whatever you want,’ and I’d wind up with nine different vocal tracks on every song. I had so much great stuff to work with.

“I had this theory: Instead of making an album that people would love, I made a record they would hate. As a kid, I remember my favorite records were the ones that were always voted the worst by certain magazines, so I figured I couldn’t go wrong if I went that way.”

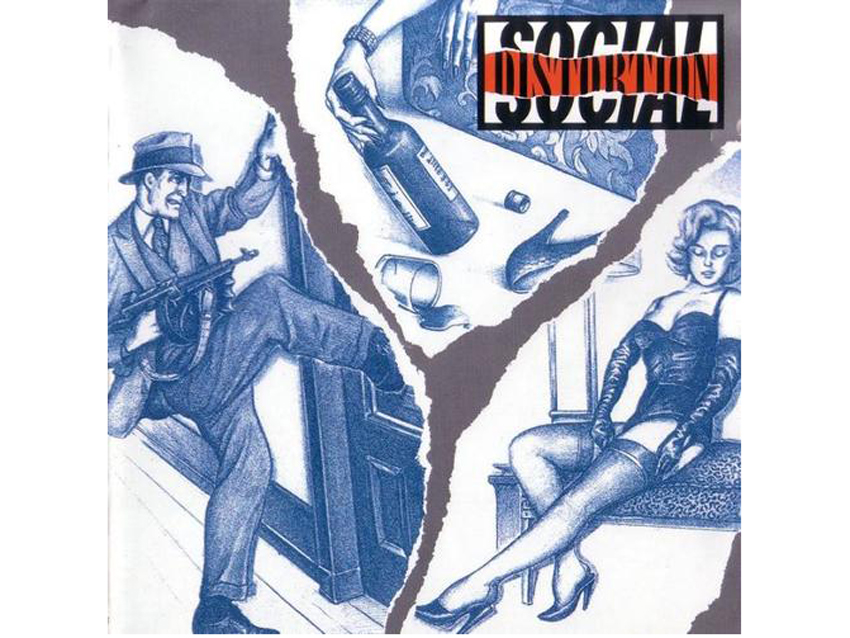

Social Distortion - Social Distortion (1990)

“Mike Ness had done some time in prison. After he got out, he made a record called Prison Bound that was really good. Nobody was really that interested in him or the band. I met with him and thought he was great – the real deal. He was into Hank Williams and all the solid stuff, so we hit it off.

“I recorded them, and again, my idea was to just capture them as they were and not do a lot of production. Pretty much everything was cut live in the studio. We did some percussion overdubs, some tambourine and a few backgrounds, but not too many.

“It all worked, and the record did really well. To this day, it’s doing well. I’ve done a lot of records that were supposed to be huge, and they did just OK. Nobody expected anything of Social Distortion at all, and they got a ton of radio play and racked up sales. To me, they’re the kind of band that should be on the radio.”

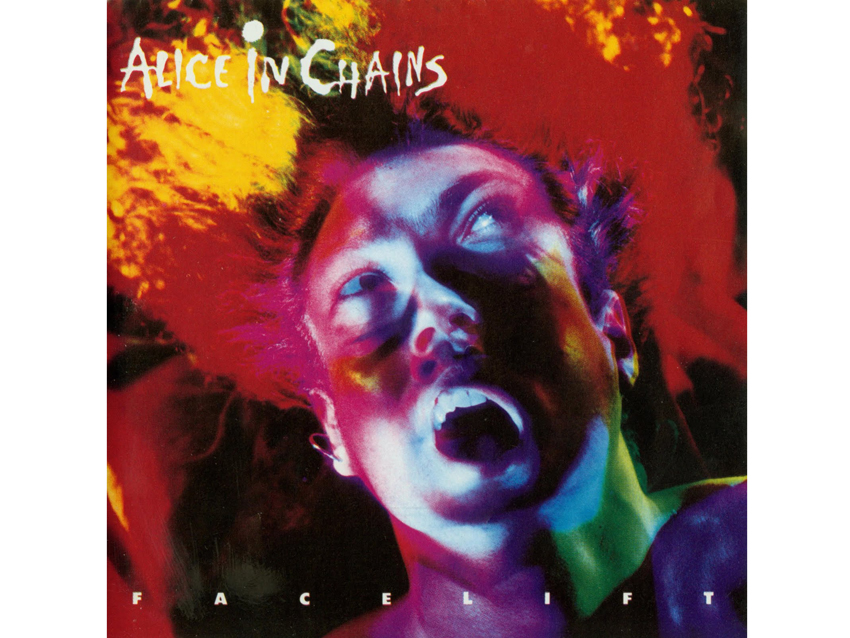

Alice In Chains - Facelift (1990)

“When I met with the band, I told Jerry Cantrell, ‘Metallica took Tony Iommi and sped him up. What you’ve done is you’ve slowed him down again.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘You got it.’ That’s how I got the gig. I totally understood what they were doing.

“A lot of producers – big producers – passed on the band because of Layne Staley’s voice. I loved his lower vocal sound, which was different from Gun N’ Roses and some other bands who were around then. Layne had one of the best singing voices I ever heard.

“We went to London Bridge in Seattle. The crew was great; Rick and Raj Parashar, who ran the place, they were terrific. It was a nice vibe. We cut basic tracks there, and then we went to Capital Studios in LA to do overdubs. I mixed it at Soundcastle over in Silverlake, which is where I did Jane’s Addiction.

“I never had any problems with the band on this record or on Dirt. There were some problems later on, which had to do with Layne’s addiction. But they were hot and ready to go on the first album. They did some drinking, but there were no drugs. It was funny: They wanted to know where the strip clubs in LA were. We were driving down Hollywood Boulevard, so I pointed to one called the Tropicana.

“A little while later, I went to see the band at the Oakwood apartments, where they were staying, and there were naked girls running around everywhere. I saw a Tropicana calendar sitting on a table with all these “X’s” over pictures of the girls’ faces – they were all the girls they had pulled from the club. [Laughs] Total rock ’n’ roll. They were livin’ it.

“I love this record. To me, it’s better than Dirt. The band had so much raw energy at the time, and it really comes through on the first album.”

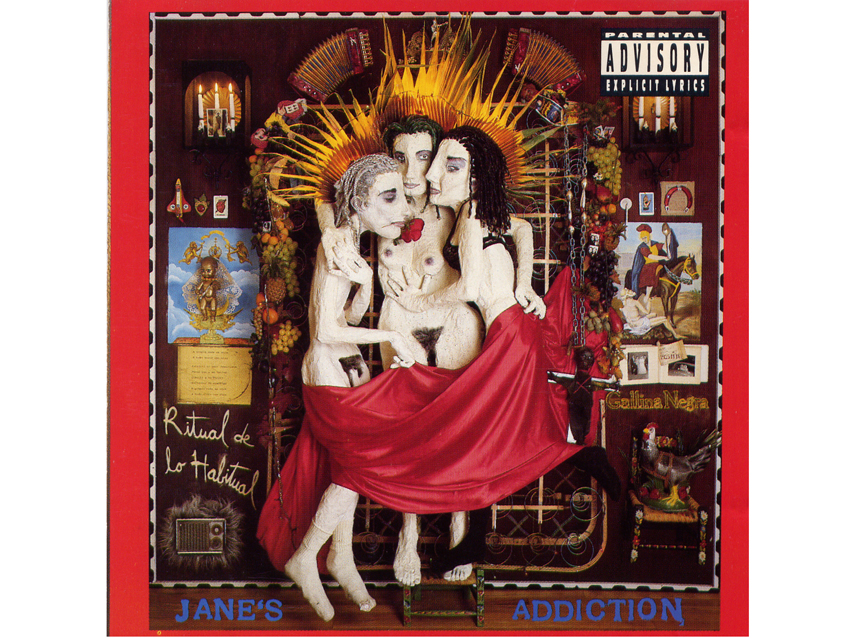

Jane's Addiction - Ritual de lo habitual (1990)

“I love this record. Of all the albums that I’ve done, this is by far my favorite. It’s got such a great vibe. Interestingly, Perry Farrell was in a really dark place when we made it – the whole band, too. A lot of it comes out in the music. It’s sad and strange but somehow really cool and wonderful.

“That long demo that I had for the first record? Nine songs were left, so those were the ones we did for Ritual. Nothing new was written. If you notice, it starts off with the same sounds as the first one ended, and then it kind of opens up production-wise.

“Been Caught Stealing had a neat trick to it. We had trouble getting a good feel – nothing the band did sounded right – so I asked Dave Navarro to pick up an electric guitar and play it unplugged. We put him in a vocal booth and miked him, but he didn’t go through an amp. An acoustic guitar would have been too loud, but an unamped electric had a real nice sway to it. We laid down a few tracks, and then I had Stephen Perkins play drums to that. It’s a great groove.”

Alice In Chains - Dirt (1992)

“At first, they were very energetic, but by this time, they were a big, established band, and the vibe was different. They were getting jaded. Layne told me that he didn’t like being famous. He told me flat-out, ‘People look at you like you’re a piece of merchandise.’

“The material was great; I knew it was going to be a strong record. We recorded it at One On One, where Metallica did their Black album. Lars told me that they had this 31-inch woofer for the kick drum. I rented a PA system and put the kick drum, toms and snare through this woofer plus these huge side monitors. That went into the room sound, and it made the drums sound like artillery going off. I credit Lars with turning me on to that room.

“The basic tracks went down easily, more so than what we did with the first record at London Bridge. We finished at One On One, and then we went to Eldorado to do overdubs, including Jerry’s guitar parts. I did the mixing there, too. That’s where I developed the style of blending Jerry’s sound, using the highs, mids and lows from three different amps.

“I had two 24-track machines, and I used 16 tracks for Layne’s vocals. I tripled-tracked him, and he sounded great. He knocked out his parts and just sang great. I made this effect using delays on Layne’s vocals with an Eventide Harmonizer; in fact, I called the effect ‘Layne Staley.’ Reverb can darken things up, but delays keep things hard and powerful. None of the mixes took long. A lot of them were done in just half an hour.”

Anthrax - Sound of White Noise (1993)

“Their manager, Johnny Z, contacted me, so I went to New York to see them. I had worked with John Bush on an Armored Saint record, and now he was singing with the band. We decided to make a different-sounding Anthrax record. Gene Simmons was a big fan of it, and he talked to me about maybe working with KISS. I heard the album that KISS wound up making, and it sounded like the Anthrax record.

“I didn’t want the guitar sound to be tucked into the mix. I wanted each guitar amp to sound like you plugged right into a stereo speaker. The rhythm guitar was always very dry and in your face. I started hearing this same sound soon after on other people’s records.

“The kind of metal that the band was making wasn’t mainstream at this point. They were harder and more uncompromising. They were in a bit of a transitional phase on this record. Everybody played beautifully; they were all awesome – A-class players. John Bush did an amazing job, but you know, Joey Belladonna had his fans. It’s hard when a band changes singers. A lot of the early fans say, ‘Hey, that’s not the band we love.’ So the record didn’t do as well as people might have hoped.

“I like the songs. See, I don’t make records for other people; I make records for one person: me. I try to imagine myself at 16 listening to a record, and that’s who I try to please.”

The Offspring - Americana (1998)

“I was down in the Bahamas, recording at Compass Point, and I got a call from my manager telling me that Dexter from The Offspring wanted to meet with me. Dexter flew down the next day and told me that his band and Rancid had just been offered $10 million apiece to move from Epitaph to Sony. Rancid said no – they didn’t want to lose their audience – and Dexter was afraid of the same thing. But he knew that I could work with alternative bands and bring them to the mainstream.

“We did Ixnay On the Hombre, which was pretty satisfying – it was kind of a crossover from their old production sound to their new sound. After that, we did Americana, which kind of picked up where Ixnay left off. But see, I never made a record for the money before, and this time I couldn’t say that.

“I made a ton of dough, but I was now making corporate-like records. I didn’t like that feeling. It threw me into a spin and off-balance. I always tried to do something different, but now I wasn’t. I was going for what everybody else would have. This has nothing to do with Offspring, and it’s nothing against any of them. They’re great guys, and they were fun to work with. But when I finished the record, I didn’t have the same kind of satisfaction that I once had. All of a sudden, I said, ‘Who am I? Am I the guy who’s expected to feed the radio system and make these big records?’ I kind of lost my bearings after this."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.