Production legend Daniel Lanois on 12 career-defining records

Daniel Lanois' master class in recording can be boiled down to a simple dictum consisting of just three words: No phone calls. Expanding on that thought, the redoubtable producer, engineer and musician says, “Phone calls in the studio are the enemy of making good records. If you’re taking calls and trying to line up your next project, your mind isn’t going to be on the matter at hand. If I can give one piece of advice to anybody making music in the studio, it’s get rid of the phones. That goes for everybody, but it’s especially true for the producer and engineer."

Over the past three decades, the French Canadian native has built a reputation as a renegade sonic architect, whose unyielding pursuit for "capturing magic moments" has resulted in benchmark albums for the likes of U2, Bob Dylan, Peter Gabriel, The Neville Brothers, Neil Young and a host of others. He's also released a series of his own albums, works that have veered from rootsy, earthy poetic beauty to interstellar sound exploration.

“I wake up every day thinking that I can keep reinventing sound for myself," Lanois explains. "I think my new body of work, Flesh And Machine, speaks about that subject matter. I care about innovation and breaking new ground sonically. That’s what I do every day, man.”

But for all of his audio breakthroughs (some of them arrived at by months of virtual studio lockdown – "and no phone calls; that's a must"), Lanois insists that the human element is still the principle element driving all of his recordings. “We can never lose sight of the fact that we’re working with people," he insists. "We’re making records for people to listen to. I mean, equipment and technology exist as a necessary carrier for the sound that we replicate for people to hear, but you always have to hear the heart of the artists making the music. If you lose that, you've lost something important."

Lanois developed his aesthetic sensibilities as a teenager, recording local bands in the own studio n the basement of his mother's home in Ancaster, Ontario. From there, he began working with up-and-coming acts like Martha And The Muffins and Slightly Saucer before his work caught the ear of Brian Eno, the former synth player for Roxy Music whose recordings with Robert Fripp, David Bowie and Talking Heads proved to be transformative game-changers.

"I think even early on, I had a desire and a willingness to follow my instincts," Lanois says. "I never went to school for producing. Knowing how to listen and to understand things like chemistry and philosophy, things that are all intertwined, these aren't things that you can learn in school. And you know, being talented helps. You can't just say, 'How can I learn to be Leonardo Da Vinci?'"

Given the wide range of music that he's helped shape over the years, one might be tempted to spot a hole or two in Lanois' resume, like heavy metal. And asked why he's never worked with metal band in the past, the producer offers a straightforward response: “Nobody ever asked," he says with a good-natured laugh. "I was never asked, so I never went there. If an invitation came in, I'm sure that I would have looked at it."

On the following pages, Lanois looks back at the making of 12-career defining recordings, including his new solo album, Flesh And Machine, due out October 28. “I always want to make records that have a lot of soul and that people could keep coming back to," he says. "I’d like to think that the records could live on, be points of reference and be forever fascinating. My criteria has always been the same: to invent new sounds and make soul music. That’s pretty much it."

Harold Budd/Brian Eno - The Pearl (1984)

“This was a very concentrated time for Eno and me. We were very devoted to his vision of ambient records. The Pearl, of course, is a Harold Budd record. He’s a beautiful piano player with just so much feeling in his musicianship. He comes up with very unusual chord changes.

“It’s a very transporting record, and that’s what I love about it. It takes a listener on a real journey. This is one of the first records where I learned that you have to concentrate on your work. Don’t take phone calls. Respect the matter at hand and finish the work that you’re doing. Try to turn it into a masterpiece and then take a little bit of a break and see what you’d like to do next.”

U2 - The Unforgettable Fire (1984)

“It was a lot of traveling for me, and I got to work in a location outside of the average studio. We were in a castle, so I had to make that work. For me, it was the beginning of mobile recording and flying equipment around in cases. On a sheer physical level, it was a very new experience, doing something outside of a conventional studio.

“The band wanted to be in a location that had some life in it, a place that had a sense of history. We were treating it like a show, really. We set the whole studio up around the band rather than bringing the band to the studio. It’s a more renegade way of working, but I see it as bowing down to the music as opposed to bowing down to the studio. I think it was a milestone in that way.

“The band wanted to broaden their scope and really concentrate on their vision, but I don’t remember them saying specifically, ‘We want to change our sound, so that’s why we brought you guys in.'

“I treated the song Pride just like all the other children on the record. It’s the one that took the longest to cut, actually, because we could never get the vibe right. We didn’t cut that one in the castle, though. In the end, we did it at Windmill Lane in Dublin. I had to bring in a whole bunch of bricks to build some kind of a stone wall behind Larry to get the drum sound going. It worked out pretty well in the end. It’s got a lot of power to it.

“It’s in a very high register for Bono – he was singing at the top of his range. I think he hit the B, which is pretty high for a tenor. I was very impressed with the fact that he was reaching to the top of his range for the top note of the chorus, going as far as he could.”

Peter Gabriel - So (1986)

“I liked making So with Peter because I had already made a record with him, the soundtrack for a movie called Birdy. We were already working together and things were going pretty good, and so he invited me to work on his singing record.

“We just kept going in the same location, in an old farmhouse that had a studio set up in a cattle barn. It was nice and private, and I liked that. It’s in the west country of England, a little village called Ashton, so there weren’t too many distractions. When I work, I don’t do anything else, so the less distractions the better.

“As I said earlier, I don’t take a bunch of phone calls or try to line up the next big thing. This was the opposite of cellphone times because we didn’t have cellphones then; you couldn’t even make a phone call out of the west country of England, so that was a plus. I remember there were a couple of calls, but I ripped the phone out of the wall and threw it on the ravine. [Laughs]

“With Peter, I just went one step at a time. I don’t think there was a lot of discussion about the sonics, other than I put a lot of time into my own development of the sound of that record in the absence of Peter. I’d prepared some sounds for him and then he’d come in the next day, and I’d surprise him with what I had. We just kind of build one brick at a time with the sounds.

“We agreed that some songs weren’t written yet and that we shouldn’t have the rhythm section in until all the arrangements were formed. That record was built on top of a beat box; every song was recorded to a rhythm box. Only after we had the arrangements in order and everything was cut to the beat box properly, that’s when we brought in a drummer and bass player as the last two components.

“It’s not something I would recommend because then you don’t have the feeling of a rhythm section around you, but it was necessary for us to do it that way because we wanted to finish the songs before we put in the drummer and the bass player. For us, on that record, the approach worked.”

U2 - The Joshua Tree (1987)

“At that point with U2, we pretty much had a momentum working in our favor. We had done The Unforgettable Fire, and everyone was very happy about that. I also had a hit with Peter Gabriel – I think we already had a number one hit in America.

“So when I walked into the U2 studio, there was a lot of confidence in the air: ‘Maybe the French Canadian’s got something after all!’ [Laughs] ‘Maybe that halo of hit making might be following him around.’ The band was very happy for me, because I was just a kid then and they didn’t know me from Adam. I think they really appreciated that I was able to go to England and work with Peter and do something special for him, and they realized that my level of commitment and care for the work was really strong.

“We brought in one new sound for the guitar. A friend of mine, Michael Brook from Canada, who was my roommate at the time – he’s a scientist and a musician – he invented the Infinite Sustain guitar. That’s the guitar you hear on With Or Without You. We nailed that one pretty early on because Edge had just gotten one of these guitars from Michael.

“We plugged it in, and it had a really cool, stratosphere tone to it. We quickly overdubbed two parts, two passes, on With Or Without You just to try out the guitar. Those are the performances on the final mix. It was just a cool new device designed by Michael, and we were all excited about it. That’s often the way it goes with gadgets and new sounds – it’s just thrilling as a new discovery, particularly when you can do something with it.

“I just dealt with every song, every note. As each new thing came through the door, I gave it every ounce of blood that I had. There wasn’t a very philosophical strategy about what sound to embrace and all that kind of thing – I never worked that way. It was just ‘What have you got in your hands? What have you got to say?’”

Daniel Lanois - Acadie (1989)

“At the time, I was renting an apartment in New York. Forty-Eighth Street is where I bought all the equipment that I needed to make a record. I bought two guitars from We Buy Guitars, a Les Paul Junior and a Jazzmaster. Then I got an Akai 12-track recorder, a Hill mixer, a Korg HDD3000 for my guitars, a couple of mics and some cables, and I threw everything in a trunk of a taxi cab.

“I went back to my apartment, and I monitored everything through a blaster. I had a pretty nice blaster, so I blasted it right in my face. I used the Korg for my guitar, so it was essential a DI. I didn’t have to make too much of a racket in the apartment building, and then I got started. After maybe a month of that, I decided to go to New Orleans. A friend of mine drove my equipment down to New Orleans, and I took the train and set up down there for a while, and that was it.

“I fell in love with that city, not only for its architecture but obviously there is so much music history that’s come from there. For an Acadian kid to be in the South and to hear those tuba bass lines, it was great. I hung out there and made a record with the Neville Brothers.

“It was a big education for me to be hanging out with Art Neville and George Porter and some of the forefathers of funk. A massive education for me. Some of that made its way into my own record. At that time, it was a sort of a trilogy, because I did Yellow Moon with the Nevilles and Oh Mercy with Bob Dylan and my own record – they were sort of back to back over the course of months, really, not years."

The Neville Brothers - Yellow Moon (1989)

“I’d built a studio for The Neville Brothers at the end of their street. They live on Valence Street, and I built the studio on St. Charles in an old apartment building. That way, we didn’t have far to go, and I think they really appreciated that we assembled a very fascinating studio in the name of doing good work, of proximity and otherwise.

“At that point, I was giving acts kind of one price for everything – 150 grand. That’s what I charged them for everything, and I took the 150 grand and bought a bunch of equipment. I just guaranteed them a record for $150,000. I think I did the same deal for Bob Dylan, 150 grand for everything and no questions asked. I said to the managers, ‘Just drop it in my bank account, and I’ll deliver you a masterpiece. What do you think?’ We shook on it, and that was that.

“We started, and because they didn’t have to fly anywhere, it made a lot of sense. So that’s the intelligence of that record, that we were able to really harness it properly because it was a neighborhood record. I made a point of meeting a lot of different folks that the Nevilles had been associated with, just to find out where the songs came from so I could have an understanding of the lay of the land. That was a beautiful experience for everybody.

“We all huddled up in this little room, and it was there that I recognized the talents they all had as percussionists. I made sure that everybody played percussion on the record. I just got everybody to jam out for a while, and then they’d leave, and I’d find the best 32 bars and loop them. The whole spine of it, really, is a rhythmic jam. They could come in and play the song on top of their own loops. It’s like sampling the Nevilles.”

Bob Dylan - Oh Mercy (1989)

“It was pretty cool. I told Bob I was in New Orleans and that I was making a record with the Nevilles. He said he was coming to New Orleans on tour. He stopped in and I played him a few things that I’d done with the Nevilles, and he played a few of his own songs, including With God On Our Side.

“He thought what I had sounded really great, said that it sounded like a record with a very powerful delivery by Aaron. I think he just appreciated that we had really committed to a setup there and that I was serving the brothers quite well.

“He understood that this was not some generic operation. These were people who would come in to do their work and were willing to live it and breathe it and go the distance in trying to make a masterpiece. I think he was able to spot that I was at a peak of sorts with my own work, and he was happy to be part of it.

“Later on, I visited Bob at his house a couple of months before we jumped in. He played me Most Of The Time and some others, which I thought were very special. I figured that was enough to go on. In regards to an approach, I don’t tell people too much. I just sat Bob down in my chair and I sat on the other chair. I had already gotten guitar sounds, so we didn’t have to waste any time with that.

“I just presented him with my 1951 Telacaster – I also had a great acoustic guitar that Bob played. He didn’t bring any of his own instruments or anything. He just used the setup that I had designed for him. A little bit like with Peter Gabriel, we cut most things to a beat box – I used a Roland 808, and that was it.

“I put a big Electro-Voice monitor in front of Bob, and we piped the beat box to him, largely just the 808 bass drum, and so that was the setup. I sat two feet next to him to make sure that we had a great vocal sound and that the center of songs were properly respected.

“Bob is pretty much a one-take guy, although on the song Ring Them Bells, for example, which was all vocal and piano, he changed one of the verses and a week later wanted to make sure that he included his new verse. I had to replicate the sounds and essentially chopped the new verse into the original. It was a little bit of a challenge, but I think I got it pretty good in the end.”

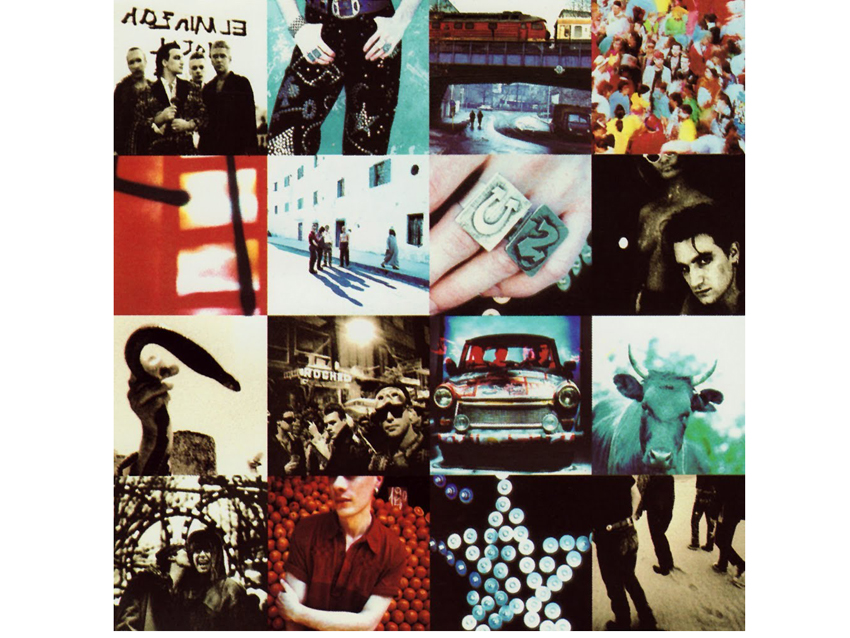

U2 - Acthung Baby (1991)

“We went to Germany, to Berlin, because at that point Bono was talking about making a rock ‘n’ roll record but a European one. Eno had already worked at Hansa Ton [Studios] with Bowie in the ‘70s, so there was a lot that had come before us. They thought it would be an interesting environment to come up with this new European rock ‘n’ roll approach. I liked it there, and I thought Berlin was cool – actually, it was pretty cold because it was the wintertime.

“It was a big old orchestra room, a fabulous space, but the control room was down the hall, so it was a little odd because we were communicating by camera. In those days, I was playing with the band in the room – I always played with the band, whether I was playing percussion or guitar – and then I’d run in and check on the sounds with Flood.

“It was a very inventive time. We had some pretty smart cookies in that room: Eno and The Edge – Flood and I could be included in the smart club. We were really on our sounds and innovatively driven. At every bend of the road, we’d look for something special that could provide the band with new sonic and melodic discoveries. It was a really great time. We batted around a lot of things that never made the finish line, but that’s normal.

“We did a lot of the guitars in the control room – that’s how many of the new sounds happened. We always had some amps in the hall behind the control room to patch in to. A lot of it was just from fiddling around with various pedals. I think we were using the Korg A3 – that’s where you get that ‘Bow-wow!’ sound from Mysterious Ways. Funnily enough, we used a Randall amp for a lot of this and not a Vox – The Edge is really known for the AC30. I think it was just some amp that somebody dragged out of the back room because we just needed something to listen to. It was a zebra striped one, I think.

“As always, a big part of my job involved listening for any turning points, no matter how small, anything that would lead us to some kind of inspiration. Sometimes it was just a little guitar part that would spawn a whole other level of innovation. That’s when you need to be a great spotter and be smart enough to notice things that are special. Whether it’s a little chord sequence for One or some kind of riff, you have to spot each moment and keep track of where something came from, what equipment was used, all of that. Then you stack those moments up, present ‘em to the band, keep your notes, keep everything earmarked. When you’re making records, oftentimes the by-products are significant; the little sidebars can become the center of the picture quite easily.”

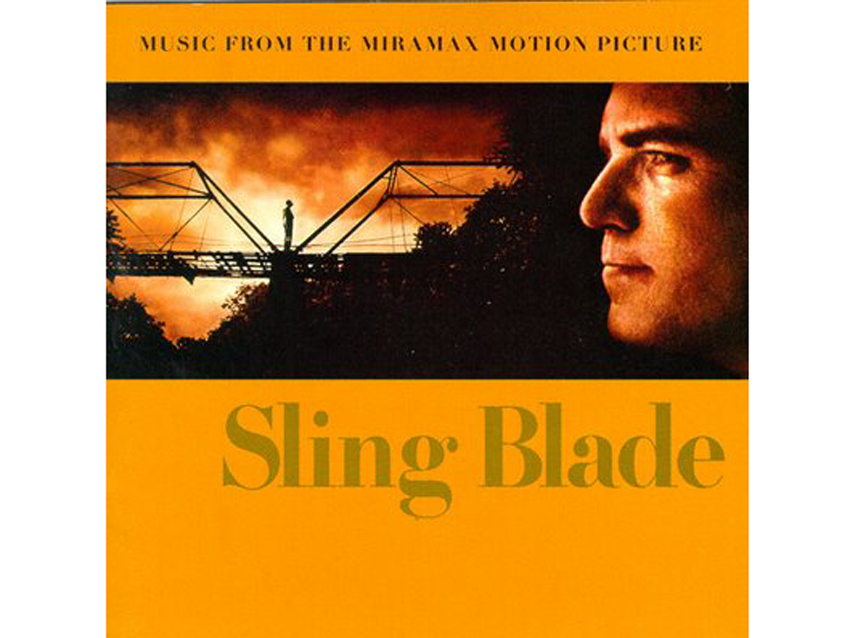

Sling Blade - Music From The Miramax Motion Picture (1996)

“I was renting an old cinema in Oxford, California at the time, a little Mexican theater. That was my shop, and that’s where I met Billy [Bob Thornton]. He liked my first record; he thought it had a strong vibe to it. But what he also liked was the idea that we’d be making a soundtrack for a film in a film house. How’s that for a bit of genius?

“It was a great time working with Billy because he was all about having a one-on-one relationship. He’d give me a little bit of slack at work for a day or two on my own, and then he’d roll down and check out what I’d done to some of the scenes; he’d make some suggestions – ‘What about this? What about that?’

“It was a great way to work. There were no boardroom decisions overriding anything that we were doing; we made our own decisions. That’s why that project has sort of a pure and true sound to it – we didn’t have a lot of opinions floating around. I don’t even remember there being a music supervisor – I don’t need to be supervised. We didn’t put in a bunch of pop songs or anything like that. It was pretty much how I imagined Fellini worked with Nino Rota.”

“I didn’t read the script – I don't read scripts. The movie was pretty much shot already, so Billy would show me scenes. I realized that there was a child-like element in the film given that the character of Karl was a grown man but was still was a child in some ways. I wanted to maintain that element of wonder in him as a character. I was able to play with that a little bit. I wanted it to be sophisticated, but I still wanted it to unfold like kids seeing things for the first time. I think we managed to get the music there a good few times.”

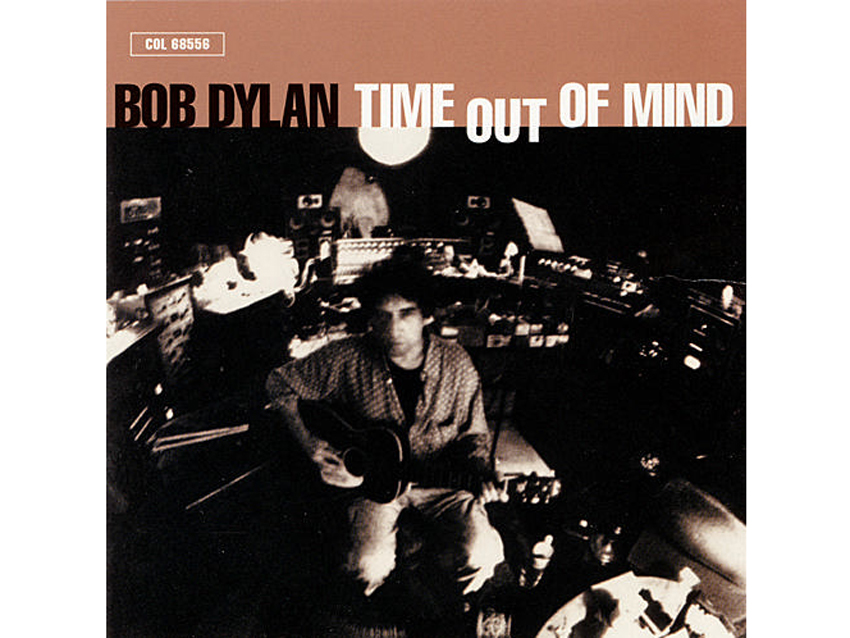

Bob Dylan - Time Out Of Mind (1997)

“I started Time Out Of Mind in the same theater where I did the soundtrack for Billy. We cut a lot of demos there, me and Bob, and I had a drummer friend of mine hanging around – his name is Tony Mangurian.

“We had this little trio, and we knocked out a good few of the songs. We really hit on a sound there, something very special. Bob wanted to work in Miami, so off we went. We put all the equipment into a truck, including a couple Morris echoes, and just shift everything out to Miami.

“We continued with the record there and put an 11-piece band together. The first drummer on the session didn’t work out, so I brought in Brian Blade and Jim Keltner. I was reassured that I had one of the best rhythm sections in the world. Tony Garnier on the bass – he’s a monster. Given that we were making a blues-based record, I wanted some of the people to be from the south. Brian Blade came up in church playing for his dad’s choir, so that’s a guy who really has an understanding of shuffles. He’s one of the masters of the hi-hat. That was my main contribution to the record, to have Brian Blade in the room.

“From there, I felt reassured that I had the rhythm section sorted out, and I made a point of asking the musicians to not play any diddles – no Nashville diddles, no ‘dweedly-dweedly-dweedly’ on the guitar. I didn’t want any guitar playing. I just wanted people thinking of themselves as trees and landscape, just serving the center. I gave them a little speech that way. I said, ‘I don’t want Nashville picking,’ because a couple of the guys were from Nashville. ‘No twangy guitars, no picking.’

“I told them, ‘If you’re going to play a note, it has to harmonize with Bob. No random guitar picking.’ Every note on that record is supporting the melody. I played the main guitar parts because I knew the arrangements really well. I plugged in my Les Paul and was essentially the bandleader. But if anybody picked, I threw them out of the room. [Laughs]

“We won the Grammy for Album Of The Year. Not bad for a French Canadian kid.”

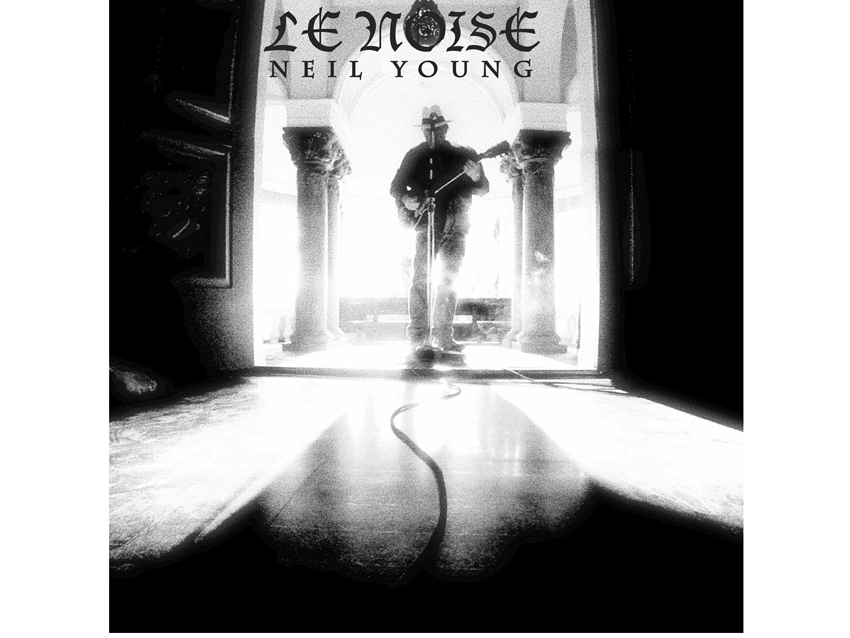

Neil Young - Le Noise (2010)

“Neil was talking about going to New Mexico to make that record, and I said, ‘OK, let’s consider that. I’m all set up here in Silver Lake – why don’t you stop in, and we’ll do three days and see how it goes?’

“I had a nice collection of Fender amps from the ‘50s – Neil likes those kind of amps. Plus, I had some nice guitars, like this beautiful little Guild all-mahogany acoustic that I’ve had since the ‘70s. Neil told me he wanted to record acoustics, so I set up a really good sound for him, putting a C24 mic on it, but I also had a pickup on the guitar. I sent the signal down the hall to a couple of different amps. It was a very five-dimensional guitar sound.

“As soon as Neil walked in the door, I put my guitar in his hand. He loved the sound, and that’s the guitar he used on the record; he didn’t even use his own. It was very fortuitous that I was able to anticipate what Neil might like, because when I presented him with a beautiful sound, he knocked out a couple of acoustic numbers that really set the tone of the record.

“Then he had his Les Paul with him and plugged in to some of my amps. I got this monstrous sound in the foyer of my house, my studio in Silver Lake. That was it – he said, ‘Well, I guess we’re not going to New Mexico. We have it in here.’

“He only works during full moons, so we did four full-moon sessions. Unfortunately, I crashed my motorcycle toward the end of that record. I nearly died. Neil was very helpful to me and made some calls to some doctors. He got me some special help, so I’m forever grateful for what he did for me. I finished mixing the record in a wheelchair.”

Daniel Lanois - Flesh And Machine (2014)

“With this album, we hope to leave cinematic window of opportunity open for our listeners, to allow their imagination to be a part of the process. I think this record takes people on a journey, but it's one that lets them make up their own minds about what that journey really is.

“It was very complex, with a lot of deconstructions. Like on the song Two Bushes, one of Rocco DeLuca’s songs, I did a bunch of processing on that. He wanted more out-of-body sounds, so I built these two tracks and made them pretty far out. He came over and I said, ‘Let me take the song out so you can hear what I’ve done.’ I just played the tracks of processing.

“He said, 'That’s fantastic. Let’s use it just like that.’ We put it on his record and we put it on mine as well. Those are the sounds that were meant to be in the shadows of a more conventional song. The conventional song was removed altogether in favor of what was meant to be just details in the background.

“Fundamentally, the song The End was a guitar performance with Brian Blade on the drums, so it’s just the two of us, and I just added everything else on top. The guitar still comes through – all the dive bombs and all the processing are derived from the guitar. Some of them are drum dubs, as well. It’s a seriously processed piece of music. I played it for Robert Rodriguez, and he said, ‘If I used that for a scene in a movie, I wouldn't need any sound affects. You’ve got the whole thing covered right there.”

“Opera is a cool piece. That’s the way I’m doing it on stage – I’m basically taking the studio to the stage. You can see on YouTube how we’re providing a rendition but one that belongs to that particular moment. I used an eight-track little multi-player, and I dubbed off of those ingredients; every time we perform it, it’s a different rendition. I’m very excited about this piece because that’s what I’m taking to the stage for a good part of my set now. The dubs are spontaneous – sometimes good, sometimes bad – but when they’re good I really amp them up, and I can hit a second dubbing machine from the first. It’s risky business. [Laughs]

“I started the album as a more conventional song record, and I had some pretty good songs – they’re still around – but then I started monkeying around with processing and dubbing and all of that, and that became more interesting to me than the songs, so I got rid of them. I thought, ‘OK, this is what we used to do with Eno. We’d start with one thing and it becomes something else – it’s more interesting.' You just have to be humble enough to abandon what you thought was your strategy and plan, but that’s a luxury that we are afforded in the sound world. I’m very proud of this record in that way. I think it’s some of my best sonic work.”

Flesh And Machine can be purchased at this link.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.