Production legend Bob Rock talks about 16 career-defining records

Although he has one of the more enviable jobs on the planet, producing mega-selling albums for the likes of Motley Crue, Bon Jovi, Michael Bublé and Metallica (including the latter's 1991 self-titled 30-million-seller), Bob Rock admits that the role of big-time record maker wasn't his first career choice. “When I was a kid growing up in Winnipeg, it was all about hockey for me," says Rock. "I was such a fan. For a while there, hockey was everything."

Like it was for millions of children of the '60s, Rock's world changed dramatically when he caught sight of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones on TV. Practically overnight, the kid who could never get a hockey stick out of his hands was now cutting out cardboard guitars and miming Fab Four songs with his friends. "We stood on our desks in school and did Twist And Shout," says Rock. "From that point on, I was obsessed with music."

Rock got himself a real guitar and played in bands throughout his teens. In 1973, he traveled to England with his friends Paul Hyde and William Alexander to test out the musical waters on the other side of the pond. "We tried to become rock stars," says Rock. "That didn't work out, do I came back to Canada and started working construction."

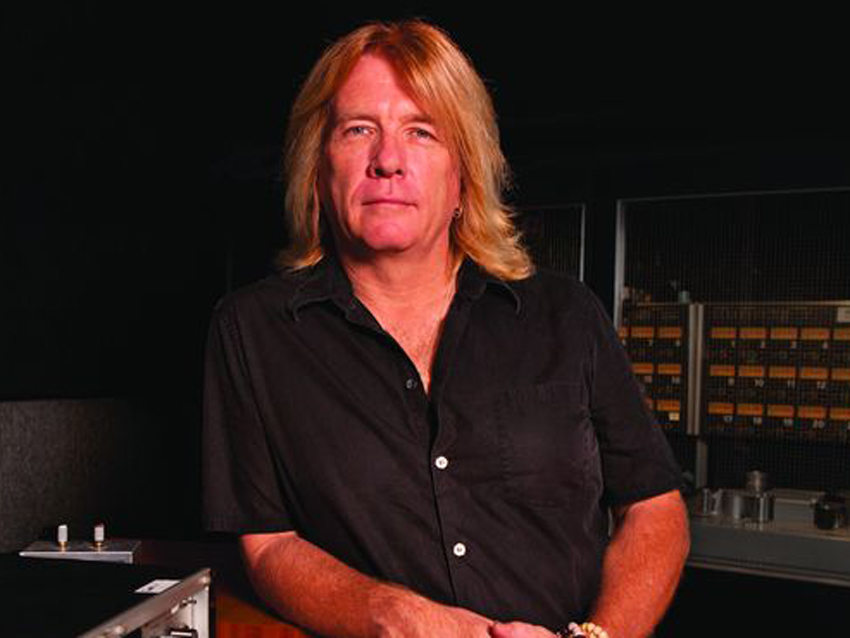

Fascinated by the sound of certain records ("The Beatles, The Beach Boys, Led Zeppelin – and Queen. Queen were a huge influence"), Rock took an introductory recording course and landed a job at Vancouver's Little Mountain Sound Studios. "I was making tape copies and cleaning up – things like that," he says. Around the same time, Rock and Hyde were making waves with their new pop-punk band The Payola$. "Paul and I could actually play," says Rock. "With punk, it was all about attitude." The band signed to A&M, and Rock, who by now had graduated to assistant engineer at Little Mountain, produced their initial recordings.

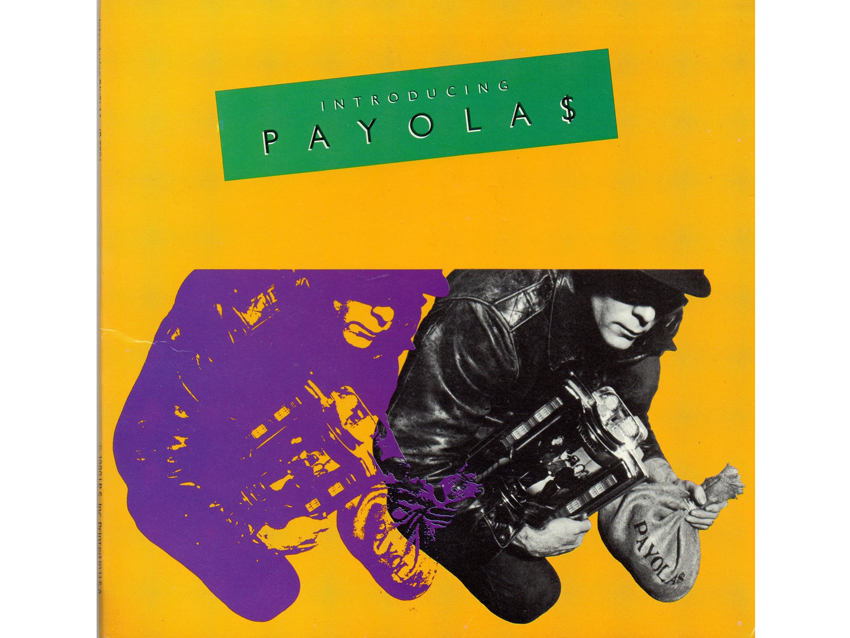

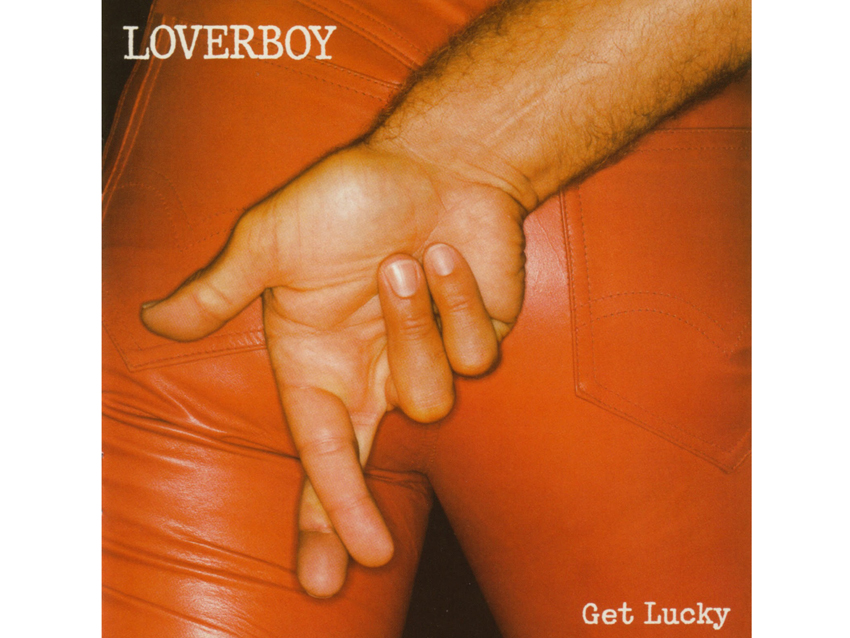

Despite several hits in Canada and a couple of flirtations with the US charts, The Payola$ failed to achieve mainstream success (by 1987, they were known as Rock and Hyde, and eventually, they disbanded, although there have been occasional reunions over the years). Rock's star, however, was on the rise thanks to his engineering and mixing work for producer Bruce Fairbairn on breakthrough albums by Loverboy and Bon Jovi, along with Aerosmith's 1987's comeback Permanent Vacation.

By 1988, Rock was flying solo, producing hard rock chart-toppers that distinguished themselves not only for their irresistible hookability but also their crushing sonics. Guitars, bass and drums didn't just have greater intensity and definition – they seemed to have actual mass. And Rock's way with singers was no less transcendent: under his watch, vocalists such as James Hetfield extended their range and reach, blossoming into full-blown storytellers.

“I’m an artist-driven producer," says Rock. "I’ve always sided with artists. You have to give them the records they want. I don’t care about managers or record companies – the artist has to be happy. Whatever the weaknesses are, I try to shore them up, and I try to play up the strengths. Some people say I’ve got a sound, but really, I just want a great sound and an album that keeps going."

Asked to describe the one key element he looks for in an artist, Rock answers quickly: "Integrity. I have to believe in the integrity of the artist. It’s why I can go from Metallica to Michael Bublé – they’re both real. It doesn’t matter if one is done with an orchestra and the other is done with an incredibly loud, heavy sound; it’s all about making the best possible records that have great songs."

And, in Rock's view, the experience of sitting down and listening to a record should be a striking one, "If a record can make you happy or break your heart, then you know it’s good," he says. "That's what I try to do."

On the following pages, Rock walks us through his incredible history behind the studio glass, starting with his own band, The Payola$, and winding up with with the multi-platinum Michael Bublé, whose next album he's currently preparing.

The Payola$ - Introducing The Payola$ (1980)

“Being in The Payolas was really the foundation of anything I’ve done. It was me learning how to make records, how to write songs, what structure meant – along with everything about the music business. Of course, working with a writer like Paul Hyde, whose integrity was always right there, was very good for me.

“The whole period of The Payolas was life-changing, and my time with Mick Ronson in the studio was huge. [Ronson produced the band’s 1982 effort, No Stranger To Danger.] He was the kind of guy I strived to be.

“The name of the band insulted the people at the record company. Charlie Minor, who ended up being murdered by a stripper, was the head promo guy at A&M in the States, and he told us, ‘I’m never going to do a fucking thing for you. Your name is an insult to what I do for a living.’ He said that with a smile on his face, even though he did help us a bit.

“The people at the record companies didn’t like the first generation of punk. They didn’t see what they were starting to develop. Going to clubs and getting spit on wasn’t for them; it was different from going to strip clubs with hot babes and cocaine and that whole ‘money, money, money’ thing.

“But without The Payolas, I wouldn’t be doing what I do now. It was very important to my development and career.”

Loverboy - Get Lucky (1981)

“They cut the drums and basics at another place, and I recorded the vocals and mixed it. I had worked on the band’s first album, too. This record was the first hit I ever had. Working For The Weekend was the first number one song hit in America for me. So this was huge for me.

“On this record, I got a chance to work with a band that had really great players. They tutored me and pushed me to be a better mixer. Paul Dean, especially, was really on my case, but he made me think and listen and work on my craft.

“It’s funny: About two years ago, I was working with a band in Nashville, and while mixing I said to myself, ‘I’m going to put on Working For The Weekend. I have to see if I’ve gotten any better.’ I put it on, and I swear to God, everything about it sonically sounded exactly the same. So I hear music the same way I did 30 years ago. It was really interesting. Working For The Weekend is an amazing song, it really is.”

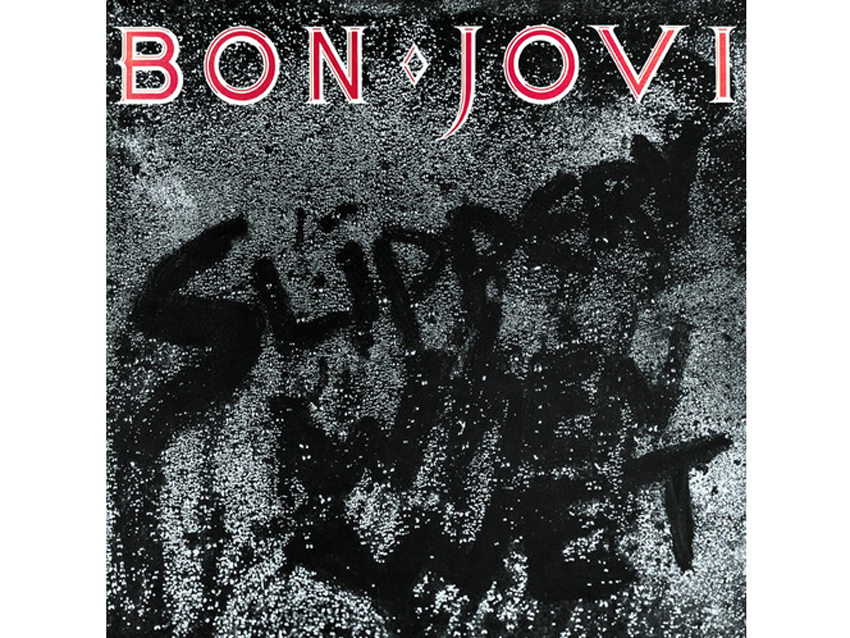

Bon Jovi - Slippery When Wet (1986)

“After Bruce and I did Loverboy, we started to get attention. Bon Jovi were beginning to get big – I saw them in Circus and Rock Scene and Creem. People were talking about them. They came up to Vancouver, and we did the whole thing in six weeks, recorded and mixed.

“The band had songs written, and they came in like a gang from New Jersey to do pre-production. But they had fun, too: they invaded all the strip joints and completely obliterated the city. We recorded all of the basics in the studio live off the floor. Everything was done very quickly.

“When Bruce and I finished it, we thought the song that could be a hit was Livin’ On A Prayer. I remember having a conversation with him at the board, and he said, ‘Well, I hope the record goes gold so we can get some more work.’ [Laughs] That’s as high as we were aiming.

“The record was one of those magical things where everything works. The engineering and mixing that I did, everything Bruce did, the way the band wrote with Desmond Child – it all came together. We tried to do the same thing with the album New Jersey, but it just wasn’t the same.”

Aerosmith - Permanent Vacation (1987)

“To me, Aerosmith were part of the same scene as the New York Dolls and KISS. They were one of my favorite bands. The opportunity to work with them was just beyond.

“At this point, my relationship with Bruce was starting to dissolve, mainly because of money. Working with him on Aerosmith was right at the time of the split. I knew what I was bringing to the table, and it wasn’t being appreciated. I left to go on the road with my band just before we started vocals. I told the guys, ‘I just can’t do this. I can’t be treated this way.’ And so I left.

“There were days when Bruce would go home for dinner, and I’d be sitting with the band. I was in the studio, and Aerosmith were right there with me. It was like, ‘Oh my God!’ You can’t even imagine how that felt. Steven Tyler and Joe Perry knew my name, for God’s sake. [Laughs]

“I did my best to make them sound as good as I could, because I was a fan. I was starting to form a lot of my ideas about production at this time. Just being with Joe Perry and Brad Whitford, sitting there and working on guitar sounds – unbelievable! Plus they’d pull out all of these guitars I knew from pictures. It was great.

“The record was huge for me. Once again, the songs were there. Some of them were written with other people, and that was a little weird for me because they were very commercial – it didn’t feel like the Aerosmith that I loved. But it was still great, though. Totally amazing.”

The Cult - Sonic Temple (1989)

“I had done Bon Jovi and a band called Kingdom Come, and those were the two albums that made Billy Duffy say, ‘This is a guy we should try.’ Basically, I worked with Ian Astbury and Billy, and we made a record. It’s the album where I really became better at being a producer.

“From Loverboy and the other things I was doing, I was more of a sonic producer. It was a learning process for me in terms of how to work with a band and get the best out of them. I was starting to get into things like arrangements during pre-production.

“Fire Woman was two songs that they had that were sort of OK in terms of feel, but we put them together to make a really great song. Putting them together was me thinking of arrangements.

“I got Mickey Curry from Bryan Adams's band to play drums, and from there I really just tried to capture the energy of The Cult. But it was also about me working with very strong personalities like Billy and Ian – a real writing duo.”

Motley Crue - Dr. Feelgood (1989)

“This came about because of Doc McGhee, who managed Bon Jovi and who also managed Motley. When it came around to their needing to change up, they thought of me. They sent me a demo tape, and I was with my wife, Angie, when I put it on. The first song was Dr. Feelgood, and I went, ‘Whoa! This is not like the Crue... ’ [Laughs] It wasn’t like the band that I knew at all.

"The part of them I liked was the New York Dolls kind of glam vibe; the whole Shout At The Devil thing wasn’t big for me. But when I met them, especially Tommy and Nikki, they thought that their music was as good as Lep Zeppelin’s or the Stones’.

“I saw that they were sober and had been so for a few months. I never knew them before that, when they were partying. They had to be sober – or else they were done. They’d burned so many bridges, and they were in trouble. So I caught a band that knew they had to deliver big-time. It was a real make-or-break time, and this would be them at their best. Tommy Lee really pushed me sonically. He said, ‘I want this to be the biggest, most badass thing ever.’ And that’s what I tried to do.

“Once again, I was developing and building arrangements and songs. I established a very close relationship with Nikki Sixx. I’m friends with all of them, but especially with Nikki. He was the guy in the band who was like the Lars Ulrich.”

Metallica - Metallica (1991)

“The truth is, it’s much like how Motley happened. At the time, Metallica didn’t mean a whole lot to me. I knew about them – I saw skater kids with T-shirts and things – but when I listened to the And Justice album, I said, ‘Where’s the bottom end?’ I didn’t like the sound of it.

“But they flew up to Vancouver with their cassette tape and played me their songs, and I said, ‘Well, this I could do. I know what to do with this.’ Sonically, and in terms of production, I was just trying to make a great record. There was no conception at the beginning like, ‘I’m going to change them.’ We just made a no-compromise record. They wanted to go to the plate with what the album is. Regardless of the fans, we made the best possible record that we could. It wasn’t me guiding them.

“In terms of sonics, that’s what they really wanted from me. They said it to me, from what I did on Dr. Feelgood and Sonic Temple and Bon Jovi and a record I did for The Electric Boys. They loved those albums, and they wanted the power of Dr. Feelgood.

“The thing was, James had songs that he actually had to sing – things like Nothing Else Matters and The Unforgiven. He didn’t know how to sing – all he did before was yell. This was the basis of our friendship. I taught him what I knew. We took the time to get the record to that they wanted and what I wanted.

“I love the Black Album. It’s probably the only record I’ve ever done that made a difference culturally across the board. It changed a lot of things.”

Bon Jovi - Keep The Faith (1992)

“The music scene had changed. In a way, Bon Jovi didn’t really matter. They were still huge, but their music wasn’t a slam-dunk. Basically, the band came to me because of the Black Album. They wanted to change up.

“It was a different process from when I worked with them and Bruce Fairbairn. The songs were different, but it wasn’t the easiest record to make. I think there are some good points on it, and there are some OK points on it.

“We had discussions about what was going on. The band knew they had to make a different kind of record; that they had to dig deep into a new way of songwriting and the way the record sounded. The production changed because it had to change.

The band was different, too. They weren’t ‘the gang’ anymore – it was Jon and the band. It was him running the show and being in charge. I was making a Jon Bon Jovi record with the band. But considering what it did, the record kind of kept them alive. I’m very proud of the album and what I did.”

Metallica - Load (1996)

“Load was supposed to be a double album of 36 songs. Here, too, the band was different. Bands are kind of like family or a marriage; there’s kids, and everybody’s trying to get the house and whatever. You’re doing this thing, you’ve built the house, but then people have to deal with one another. When I first met Metallica, they were a well-oiled machine working towards being the biggest band in the world. When they accomplished that, it all changed.

“After the Black Album, they were the biggest band in the world. They toured for two years, and then when they got off the road, it was ‘Let’s go make another album.’ But James hadn’t had any time to write. He was writing while we were putting tracks together. With the Black Album, there were demos. Stuff was there. For Load and ReLoad, it was ideas.

“The way they worked, the songs they wrote – it was a new perspective, especially for James. We were doing 36 songs, and, well, he had to write lyrics for all of them. After a year, we had four songs written – we had all the tracks but only four of them were complete – and so the decision was made to cut it in half. I took it to New York so James could concentrate on writing.

“I remember talking to him. ‘What’s going on?’ I asked him. ‘Have you lost inspiration?’ And he looked at me and said, ‘There’s plenty of hate in me left, Bob.’

“I’ve often said that, during my time with Metallica, I never had the same band I had with the Black Album. Everything was different. Which is great – that’s life. You can try to do the same thing as before, but you really can’t.”

Veruca Salt - Eight Arms To Hold You (1997)

“I liked the record they did that had the song Seether. They had Metallica’s management company, Q-Prime, and they had girls in the band – Nina and Louise. To me, this was one of those records that was fun to make. Great people, a great experience, and it was successful.

“It was almost like making Slippery When Wet – there was no drama. ‘Let’s record it, let’s mix it – boom.’ Sonically, Nina could come out and say, ‘Fuck, I wanna sound like the Black Album!’ She and I had that common ground; it wasn’t me talking them into anything. Now, a couple of the members worried about that – they liked the aesthetic they had. But I don’t know how to do ‘cool.’ I just do what I do.

“Actually, their roots were in some of the bands I’ve recorded, and I go back to what I’ve talked about before, with groups who wanted to make the best records they could make. They didn’t want to sell themselves short. That’s the essence of where Veruca Salt were at the time.”

Bryan Adams - On A Day Like Today (1998)

“I had met Bryan when he was 16 and in a band called Sweeney Todd, so I knew him for a long time. Growing up in Vancouver, I was involved in all sorts of things with him. But when I went to do this album, I really do believe that he still saw me as an assistant engineer. It was very tough for me. He didn’t really let me do what I do. He fought me on everything.

“I think it was also because of his time with Mutt Lange. Bryan knew that he had to change things up. He was writing with different people. He wasn’t working with Jim Vallance, and he wasn’t writing with Mutt, either. That was the difference. I don’t think Bryan was really confident in the record. I think he was trying to figure out what the hell he was supposed to do, how he was going to move forward without Mutt or Jim Vallance.

“In a funny way, he and Vallance had a bit of a Joe Perry-Steven Tyler relationship, or a Jagger-Richards relationship. They wrote songs together, and at some point it didn’t work; they didn’t like each other personally for a while. They’ve been writing again, and I’ve done some songs with Bryan, and it’s a lot better now. Things have to change, and people have to change, for it to work again.

“Having said all of that, I like the record. It was transitional, and it was good. It had only one hit, the Spice Girl song [When You’re Gone, featuring Melanie C], but the rest of it is really good. It’s very listenable.”

Metallica - St. Anger (2003)

“St. Anger is a fragmented record by a fragmented band. I just couldn’t do Load, ReLoad, the same sound. I couldn’t set the drums up exactly the same. This is me saying, ‘I can’t do this again.’ And they were fine with that because they were like, ‘We don’t want to do that again.’ They were searching.

“The biggest problem with the record is that we didn’t have James. James didn’t write the songs in the same way he did that made the band successful. He had his issues to deal with, and so we made the best record that we could at that time.

“Also, there was a change in music. Lars was very influenced by System Of A Down, where there are no guitar solos. Guitar solos were changing, too – there was Tom Morello from Rage Against The Machine. They weren’t wah-wah, super-fast solos. There were all of these things, and a band that was searching for something different.

“When I heard the band in rehearsal, there was a rawness to them that was really cool. The drum sound on the record is a rehearsal drum sound. It was supposed to be them in a garage. It doesn’t work in terms of the rule of metal, and the rules that people have established for that kind of genre, which basically I kicked against, because it doesn’t mean anything to me. This was my version of The Stooges’ Raw Power, only with Metallica.

“The record had to be made so they could be happy with what they do. I was the sacrificial lamb. I always wanted the band that I had for the Black Album, and I never got that band again. But if people want me to say I regret what I did, I don’t. I made it more as a friend, as somebody who was supporting guys who were struggling. That’s probably not the greatest career move, but I’m fine with it.

“The result of that, the man that James Hetfield is today, was worth it. I’d do it all over exactly the same. He’s a great man and father now, so that’s what’s most important.”

“But two people have come up to me and told me how much they liked St. Anger: Jimmy Page and Jack White. So if two people in the world like the record, and it’s those two people, I’m fine with it.” [Laughs]

The Tragically Hip - World Container (2006)

“The thing about The Tragically Hip is, they’re an iconic Canadian band that never really had the kind of success anywhere else that they’ve had in Canada. To me, it’s about the relationship with the singer [Gordon Downie], who is a very good friend of mine now. I like the band, but I didn’t really understand them much.

“When I did the record – and I think it’s one of their strongest – I really forced them to write good songs and do the work. I tried to make a record that was cohesive and to bring out the best things about the band. I really challenged them, because I thought that’s what was needed. So this is the one record where I did go in with a conscience ‘this-is-what-I’m-going-to-do’ kind of thing. I wanted them to live up to their potential.

“The band was comfortable in where they were. When I came in, I think it became difficult for them. Coming from my history with bands, and thinking of The Who and Led Zeppelin and the Stones – bands that all wanted to be the biggest in the world, that wanted to be on the radio and wanted to change people’s lives’ – that’s what I believed. I still believe in that, and I push for that.”

Michael Bublé - Call Me Irresponsible (2007)

“I did the single called Everything. I got involved with Michael because he’s managed by Bruce Allen, my manager. Michael was doing the album, and the producer, David Foster, thought that the song Everything was a piece of shit. So Bruce said, ‘I want you to go cut this song with Michael Bublé,’ and I said, ‘Sure.’

“When I heard it, Michael and I talked about it, and we made some changes. So we cut one song, and that song was a hit. Michael was going, ‘This is the guy from Metallica?’ But he didn’t know my history. Most people just know you from your biggest record.”

Michael Bublé - Crazy Love (2009)

“I did one song on Call Me Irresponsible, five songs on Crazy Love, and now I’m doing all of his new album. You know, doing this kind of record seemed perfectly natural to me. It’s just different players, different sounds. I love records – not just rock records but all kinds. And with Michael, I just make the kind of records that he wants to hear.

“This time was challenging to me because there was a lot of big band and orchestral stuff, but I just went with musicians, arrangers and people that I trusted; and at the end of the day, it really isn’t that much different from working with the other great artists that I have, like Bryan Adams and Bon Jovi and Metallica and Aerosmith.

“Michael Bublé is a rock star, man. He’s a fucking rock star.”

Michael Bublé - Christmas (2011)

“The thing about this record that’s so great is, Michael loves everything that I loved as a child. Those songs, his voice – that’s what I grew up with; that’s what my parents listened to. It was a part of my life. The Dean Martin TV show, Bing Crosby, the Christmas specials, all that stuff – it’s always been there for me. So doing this wasn’t odd for me. It was easy.

“We started the record right after Christmas, and we worked through the full year. And let me tell you the difference between a Michael Bublé Christmas record and a lot of other Christmas records: He made a serious Christmas record. He didn’t just phone it in, which is what a lot of other people do – they do a quick cover, and that’s it. He took this seriously, which is why it’s a great record. Nothing was half-assed; it was ‘We’re making a real record.’

“It’s funny: When I was working with Metallica, because those records took so long and were so all-encompassing, I didn’t really do a lot of other styles of music. Since I’ve stopped working with them, I’ve worked with a lot of different styles – Michael being one of them. And I forgot what I loved about being an engineer in the earlier days, recording gospel, recording country, and that's the fact that I just love making records. I love music. And I'm going to continue as long as the industry and the people who make records want me to do what I do. I've met amazing people, amazing musicians. It's staggering."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.