Production legend Bill Szymczyk on 12 career-defining records

“The album is titled The Long Run, but we took to calling it ‘The Long One,’" says producer Bill Szymczyk, who spent most of 1978 and ‘79 recording the Eagles’ follow-up to their mammoth-selling Hotel California. “Eighteen months in the studio can feel like a lifetime, especially when expectations are high and nerves are frayed. I didn’t think anything could get tougher than that, but I was wrong.”

Szymczyk soon met his match when he went to England to work with The Who on their 1981 album Faces Dances, their first record with drummer Kenney Jones, who replaced the recently deceased Keith Moon. “That was the hardest record I ever had to make in my entire life, by far,” Szymczyk says. “Talk about people who didn’t get along. The Who made the Eagles look like the best of brothers. It was a rough, rough time, but we got through it.”

When asked how he dealt with such notorious perfectionists as Messrs. Henley, Frey, Townshend and Daltrey, the easy-going Szymczyk says that having a sense of humour came in handy on numerous occasions. "You have to be able to deflate tensions, so being to laugh and to get other people to lighten up is key," he observes. "It's also important to be as inclusive as possible. I never wanted to be a dictator. If I had strong ideas, I’d express them, but otherwise I’d say, ‘OK, you don’t want to do that. What do you want to do?’ You've got to be willing to compromise, even when you think you're right.”

Szymczyk's career as one of the '70s top-flight record makers started, strangely enough, in the navy. "I wasn't a musician," he says. "I couldn't even play an instrument. But I was a big music fan, and in the navy I studied electronics." Szymczyk was just a couple of weeks shy of leaving the navy when, during a weekend trip to New York City on liberty, he heard I Want To Hold Your Hand for the first time. "I looked at the guys I was with and was like, ‘What is that?!’" he says. "Three weeks later, I was working in a recording studio, sweeping floors and cutting acetates, making 70 bucks a week. And I loved it. I was supposed to go to college after the navy, but once I started working at the studio, I said, ‘Nah. This is too much fun.’”

Szymczyk's apprenticeship continued at studios such as Regent Sound and the Hit Factory in New York City – he became the latter facility's first regular engineer. When he was offered a chance to become a staff producer at the Paramount-owned ABC Records in the late '60s, he jumped at it. "I felt more than ready," he says. "I had done a lot of records and demos, and I picked up a lot of tips. But the truth is, nobody can really teach you how to be a producer; it's such a subjective endeavor, and it changes all the time. Either you have the temperament to do it, or you don't."

During the 1970s, it was impossible to turn on the radio without hearing Szymczyk's work: In addition to producing the James Gang, the J. Geils Band, Joe Walsh, Johnny Winter and Elvin Bishop, among others, he helmed a passel of ginormous-selling albums by the Eagles, including the iconic Hotel California. “I consider the ‘70s to be the golden period of rock," Szymczyk says. "It was a great time, with so much creativity. The cool thing was that the inmates – the artists – were running the asylum. I don’t think we’ll see anything like that again."

Now living in Little Switzerland, North Carolina, Szymczyk continues to work – he recently produced a five-song EP for his son’s band, Some Type Of Stereo, at Mitch Easter’s new Fidelitorium Recordings studio in the nearby town of Kernersville. “Mitch built an incredible drum room," Szymczyk raves. "It’s my second-favourite drum room behind A&M out in LA. I told the band, ‘You have to play a bunch of gigs. I want to see you live, the songs have got to be done, and then we’ll go in and do it all live. We cut to tape, and it sounds incredible.”

On the following pages, Szymczyk looks back at the making of 12 career-defining records.

Chris Bartley - The Sweetest Thing This Side Of Heaven (1967)

“I consider this record to be my engineering thesis. I had been working for a few years in a couple of different studios. I wound up at Regent Sound, a four-track studio in New York, doing folk acts by day and R&B acts by night. I got to work with a lot of greats, people like Quincy Jones and Van McCoy.

“In fact, Van produced The Sweetest Side Of Heaven. Before we did the record, I had bought The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, which might have been a mistake in some ways. I remember coming home, putting it on, listening to it on the phones and just thinking, ‘Oh, God, how can anybody top this?’ It seemed as if every great idea in recording was on that record, and there was nowhere else to go.

“Van let me try a bunch of things out on this record, which was great. We did four-track to four-track overdubs. Regent was a big place, so we could fit 30 people on the floor. Van would come in with a full rhythm section, horns and strings, and I would record that to four-track. Then I would mix it down to two tracks on another four-track machine, saving two tracks for background vocals and so on. Van even let me do the stereo mix by myself. We did the mono mix together, and then he said, ‘Go ahead. You do the stereo. Experiment.’ That was great.

“It wasn’t anything like what George Martin did on Sgt. Pepper, but what was? I tried, though. I got to be creative and test things out. I wasn’t a producer yet, but I was having a ball.”

B.B. King - Completely Well (1969)

“I had already done Live & Well with B.B. before this album. The backstory here is, I was hired by ABC-Paramount Records as a staff producer in ’68. Their A&R guy, Otis Smith, saw me engineer a Florence Ballard session. The producer was struggling a bit, so I made some suggestions and got him out of a hole. Otis noticed what I did and asked me if I wanted to be a producer at ABC. I jumped at it.

“At ABC, I was assigned various bands on the roster. Then one day I noticed that B.B. King was on the roster. I’d been a huge blues fan all my life, so I went to the powers that be and said, ‘I wanna do B.B. King.’ They looked at me and said, “There’s two problems with that: Number one, you’re white, and number two, you’re too young.’ But I wouldn’t take no for an answer; I kept bugging them for months. Finally, Larry Newton, the president of the company, said, ‘B.B.’s coming to town next month. We’ll set up a meeting with the two of you, and if he likes you, you can do it.’

“I had a meeting with B, and I told him that I did all of these R&B sessions and that I knew all the hot R&B players. Instead of using B.B.'s touring band, who did the same thing night after night, I wanted to put these other guys around him. I wanted young energy, with black guys and white guys – a whole integrated thing. This was for Live & Well. B.B. wasn’t comfortable with doing an entire album that way, so we did half like that and the other half we did with B.B.’s band live.

“Live & Well did great, and we had a nice R&B hit with That’s Why I Sing The Blues. So when we were ready to do another album, eight or nine months later, B said, ‘Do it all your way. I enjoyed that.’ We had a great time, and of course, B’s biggest hit ever, The Thrill Is Gone, is on Completely Well. I didn’t know it was a hit at the time – it didn’t feel like one – but I woke up one night and thought, ‘Let’s put strings on it.’ That turned out to be a pretty inspired idea.”

James Gang - James Gang Rides Again (1970)

“I first saw the band play a gymnasium in Canton, Ohio. When I walked in, it was hard to see them – there were all of these people in the way – but it sounded like four or five guys on stage. I finally got to a position where I could see them, and I was startled to discover the band was only three guys. Wow! [Laughs] Joe Walsh was just wailin’ on guitar through an Echoplex – he definitely sounded like two guitarists all by himself.

“Yer Album we did in a week, maybe a week and a half. We had good success with that; underground radio would play the record, and a buzz started building. A bigger buzz started happening in England, especially after Pete Townshend caught on to the band. He wanted them to open up a Who tour. That's when things completely blew up for the James Gang.

“The band was quite easy to work with. Jimmy Fox was a crazed drummer who hit anything and everything – he was all over the place. And Walsh was a brilliant guitar slinger, who was really developing his skills and honing his craft. The band had built up a great following, and Rides Again furthered things along. Funk #49 is on the album. It was basically six lines and a killer guitar riff – you didn’t need much more than that. My favourite is The Bomber. FM radio went nuts for that one.”

Joe Walsh - Barnstorm (1972)

“After a few albums with the James Gang, I moved from LA to Denver. Joe had left the James Gang, and he moved to Netherland, Colorado, which is just above Bolder. He knew he had to make a solo record. One day he called me and said, ‘I’ve got a drummer’ – it was Joe Vitale, who turned out to be my favourite drummer ever.

“We started out with Joe and Joe Vitale, and then we recruited Kenny Passarelli on bass. It was a three piece again, but it was much more orchestral because Joe was overdubbing multiple guitars and playing keyboards and things like that.

“The cool thing about Barnstorm is that it was the first record recorded at Caribou Ranch. The studio was on the second floor of a barn. The studio itself was pretty much done, but there was no board, and the bottom of the place was still a dirt floor where there were stalls. Joe and I had to ask Jimmy Guerico, the owner, to put in a temporary board and a machine – Jimmy was going away to make this movie, Electra Glide In Blue. He put in an MCI 400 Series black board and 16-track 3M tape machine, along with a couple of two-tracks. There was a huge mic collection and a great piano, so that was cool.

“Jimmy left to go make his movie, leaving the rest of us to take over the studio and do our thing. It was pretty much us against the world. If anything broke, we had to fix it. But it was fabulous – we were almost in a Shining setting, very isolated, but we had the run of the place. And the music itself was unbelievable. Joe had really come into his own, and he was incredibly easy to work with. He and I became like brothers.”

Michael Stanley - Michael Stanley (1973)

“Michael would go on to have the Michael Stanley Band, but this was before that; it was pretty much a singer-songwriter thing. He’s my very best friend in the world. We still work together. I can’t say enough good things about him.

“I had signed a band called Silk to ABC in New York; it was around the same time I signed the James Gang. Needless to say, Silk didn’t have the success that the James Gang had, but I kept in touch with Michael, who was the lead singer and main songwriter – he wrote most of the album we did. I thought he had something.

“I had moved to Denver and started Tumbleweed Records. I called Michael and asked him if he had any tunes, and he said, ‘Oh, yeah. I’ve got a bushel of tunes.’ So I said, ‘Come to Denver. We’ll make a record together.’ It turned out to be the first of many. Michael’s such a great talent – I love working with him.”

The J. Geils Band - Bloodshot (1973)

“They were a very hot live band, but they needed to establish themselves on record. This one introduced them to a whole new audience, one that was radio and record-driven as opposed to performance-driven.

“The musicianship was killer on this record, and the songs were truly fantastic. The whole band was really getting their act together. Give It To Me immediately struck me as a hit. The whole reggae-ish thing was starting to happen, so they incorporated that feel in the song. The minute I heard it, I said, ‘That’s the one.’ I had to do some editing on it – it was really long at one point – but it was all right there.

“They brought in a lot of songs that were very close to finished – they weren't just parts – so we worked on the arrangements quite a bit. The band had some personal problems later on, but that was after my relationship with them had ended. When we were working together, they were a tight team.”

Rick Derringer - All American Boy (1973)

“Rick had already been in the McCoys and had played with the Edgar Winter Band. At the time, he and his manager had a unique concept: They wanted five different producers to do two songs each. They had a really good list of people – Roy Thomas Baker, me and a few others – but I happened to be the first one they went to.

“I did two tunes on the record, and I used a killer band – basically, it was Rick Derringer with Barnstorm. So we did those songs, and then Rick was going to work with other people. Six months later, Rick called me and said, ‘I’m having a hard time. Nobody’s got the time, this doesn’t work, that doesn’t work. I really like what we did, so why don’t we just do the whole album?’ I said, ‘For sure.’

“We did the whole record at Caribou, only this time we couldn’t use Barnstorm ‘cause they were having success on their own out on the road. Rick and drummer Bobby Caldwell did a lot of stuff together; it was basically the two of them. When we went back to New York, we got Edgar Winter on keyboards and sax and so on.

“It was a terrific experience. Rick had already done Rock And Roll, Hoochie Koo with Johnny Winter, but when he did it again for this album, it felt like a hit single. It was a lot more rocked-out, with a lot more guitar. It was a lot of fun to put together. Rick was incredibly easy and quite a guitar player.”

Jay Ferguson - All Alone In The End Zone (1976)

“Out of all the records I’ve made, this is my favourite. I had worked with Jay when he was in Jo Jo Gunne; we had done a couple, three albums together. Shortly after, he had quit the band and wanted to make a solo record. He called me up, we talked about it, and I said, ‘Let me put a band together.’

“To my ears, this is one of the best bands I’ve ever assembled. It was Joe Walsh on guitar, Joe Vitale on drums, another guitar player named Joey Murcia and a bassist named George ‘Chocolate’ Perry. Just an unbelievable band. We had such a fun time in the studio. The whole thing was an absolute joy.”

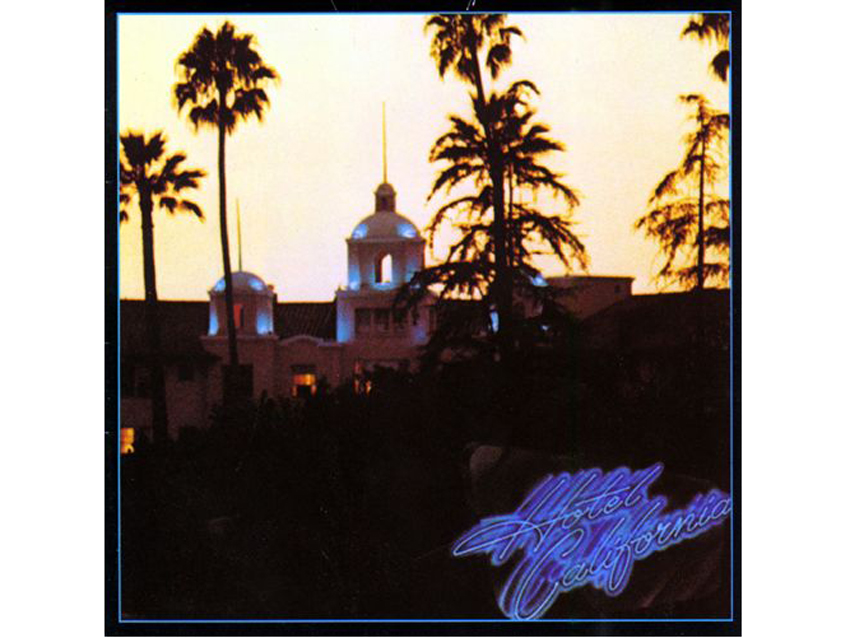

Eagles - Hotel California (1977)

“I did a few records with the Eagles, but this was the high point, for obvious reasons. The band made their first record with Glyn Johns, and that was a big success with a lot of hits on it. Their second album, Desperado, stiffed in comparison – it wasn’t a total bomb, but compared to the first one, it was something of a disappointment.

“They started their third album with Glyn in London, and after six months, things started to get shaky. The band wanted to rock out more, but Glyn was very resistant. He’d say things like, ‘You’re not a rock band. The Rolling Stones are a rock band.’ That didn’t go over so well. I would never say things like that to an artist.

“Joe Walsh had introduced me to the Eagles. I told them, ‘I don’t want to do a country band. I wanna rock!’ Which was music to their ears – ‘We wanna rock, too.’ Needless to say, we got along great. We made On The Border, which established their rock capabilities, and then we did One Of These Nights, which really did it – that was a real rock record. And the success followed: Sales doubled and tripled. So we were on well on the way.

“Pressure came along with success. Nerves were a little frayed, but things weren’t as bad as they’d get on The Long Run. During Hotel California, we knew that we were under the gun, we knew we had to produce, and we really took our time. The whole album took about nine months on and off, on two coasts – in LA at the Record Plant and at Criteria in Miami.

“It was a hard record to do, but it was such a rewarding record to do. One of the greatest moments in my life was sitting in the control room at Criteria and having Joe Walsh on one side and Don Felder on the other. For two days, we nitpicked our way through the end guitars on Hotel California. There were zero ideas at first, but we knew we had a nice long section to build it, build it, build it. ‘You do this, and I’ll harmonize.’ ‘Cool. Now I’ll play this, and you harmonize with me.’ It was incredible. Two of the most rewarding days I’ve ever spent in the studio.

“The song wasn’t together at all at first. It was just a lick, that descending line; that’s what we started with. The song was recorded three different times. The first time, when we were working on the arrangement, there were no words. We recorded it, and that’s when Henley started to get a handle on a melody and what he wanted to say. The problem was, the song was in the wrong key for him to sing. We recorded it again in the right key, but it was too fast. The third time was the charm, and that’s the one you hear on the album.

“I wasn't really surprised when Bernie Leadon left the band – coming from Dillard & Clark and the Flying Burrito Brothers, he was way more into country than rock. Funnily enough, I was initially against Joe Walsh joining. To me, him being in the Eagles would ruin his solo career, which it didn’t, so that shows you how much I know. Joe turned out to be a very easy fit in the band.”

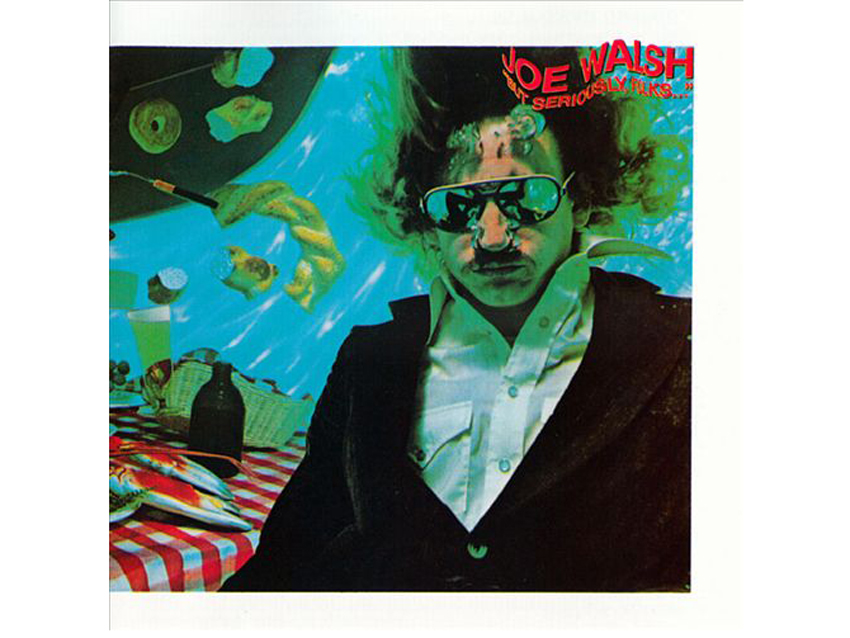

Joe Walsh - But Seriously, Folks (1978)

“Joe and I always seemed to do things in an off-the-wall way. We did Barnstorm at Caribou in our Shining-like environment. For this album, I had my studio in Miami – Bayshore Recording. Rather than go right to the studio, though, Joe said, ‘Let’s rent a boat and rehearse this stuff.’

“So that’s what we did. We got Jay Ferguson, Joe Vitale, [bassist] Willie Weeks and Joey Murcia, put them on an 82-foot motorboat, loaded up everything, and we took it down to the Keys for 10 days and worked up the songs. We had a fabulous time, and by the time we took it to the studio, we were wired and ready to go.

“Life’s Been Good started as a couple of verses. We rehearsed it as parts one and three, and Joe would say, ‘Now, when we get to this middle, we’ll all stop and I’ll come up with something later.’ We didn't really know what he was planning. Two months later, Joe worked up this other section with the talk box and the guitar solos – it was terrific.

“Strangely enough, Joe had second thoughts about putting it on the album. He thought people would take it the wrong way, like he was bragging or being pompous or something. I told him, ‘Joe, there’s no way people won’t get the humour in the song. It’s hysterical.’ Sure enough, people got it right away, and it became his biggest solo hit. But I had to work for two or three days to convince him to put it on the record.”

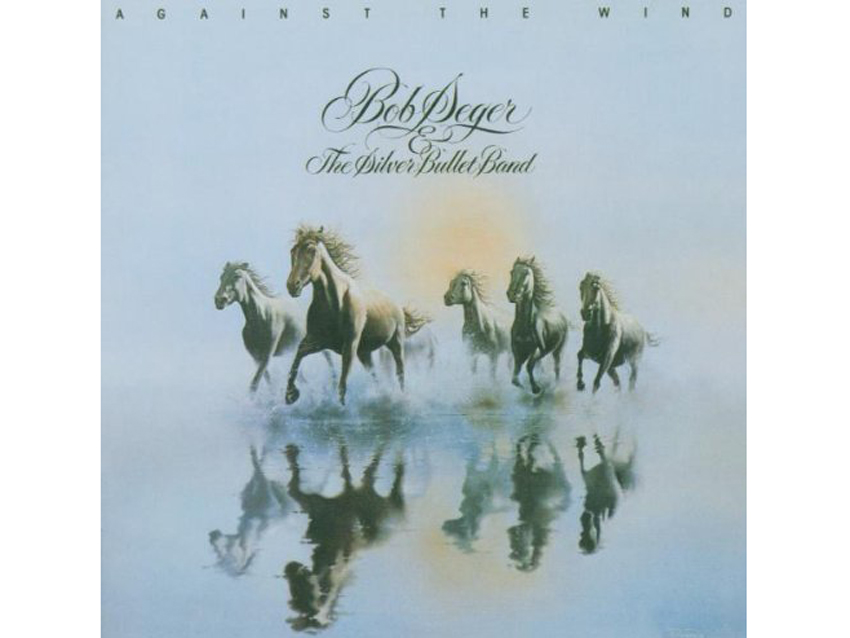

Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band - Against The Wind (1980)

“I met Bob through Glenn Frey – we were all from Michigan originally. I was a huge fan of Bob’s work. To me, Stranger In Town, Hollywood Nights, Night Moves and stuff like that was the real deal. When I heard Bob's music, I was like, ‘That’s it. He really knows what he’s doing.’ He just epitomized good old-fashioned Midwest rock ‘n’ roll.

“Bob and I got to know each other. He’d come in to help with lyric on some of the Eagles records – I think he wrote some things for The Long Run. One day he said, ‘Look, I’m about two-thirds done with an album, and I’d like for you to come in and work on three or four things.’

“We did it at Bayshore in Miami. The title cut was one that we cut, and we also did a really great rocker called Her Strut. That was another hit single for Bob. He played all the guitars on that song, too. People don’t know what a great guitar player he is. I set him up for with a delay for the solo, a repeat thing, and he dug the hell out of that.

“When he played me Against The Wind, the song, I was like, ‘It's all right there.’ Again, good old Midwest rock ‘n’ roll.’ The song was pretty much all formed; the only thing I added was Paul Harris on piano. It’s a classic song. I’m thrilled at how it turned out.”

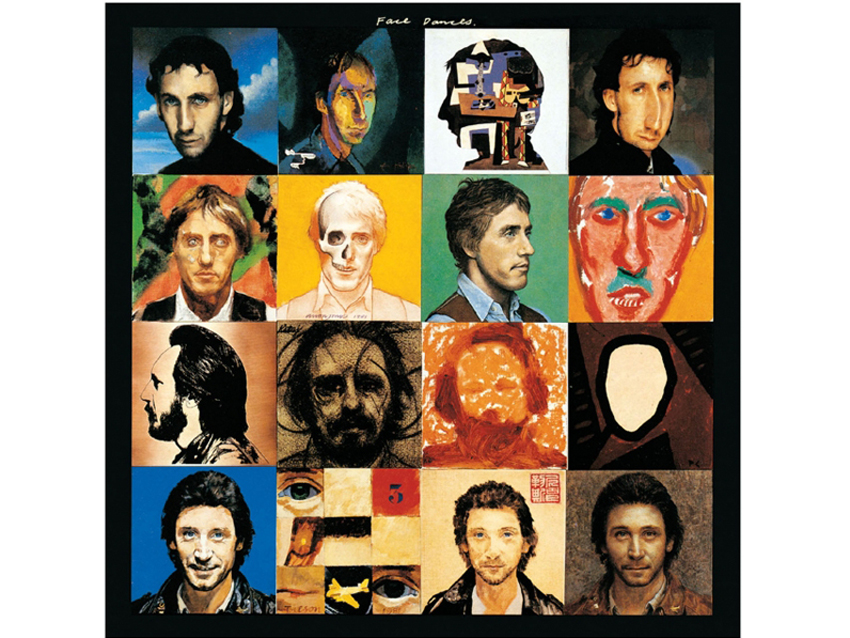

The Who - Face Dances (1981)

“I was friends with Pete Townshend because of the Joe Walsh connection. Face Dances was The Who's first record with Kenney Jones in the band after Keith Moon died, so Kenney and I were the new kids on the block. Pete was in pretty rough shape when we did this, and his relationship with Roger wasn’t the best. Roger would never be in the studio with Pete. I would ask him to come in to do rough vocals, and he would say, ‘No. When it’s time for me to sing, I’ll come in and sing.’

“So I never had Roger in the studio when we were cutting tracks, and I never had the rest of the guys in when we cut vocals. It was tough going. I listen to it now and I wish that I could remix it. I’m just not happy with what I did. I used too much compression, so I’m not thrilled with that. Plus, there was Kenney Jones, who didn’t play like Keith, so I just told him, ‘Don’t try to emulate; just play straight-ahead and be yourself.’ We both caught grief for that.

“In Pete’s book, he blames himself for the songs. Roger blames me and Kenney. And Entwistle blamed me – he and I head to head two or three times. I told him, ‘We already have a great guitar player in this band. I want you to play like a bass player.’ I actually only got him to do that on Another Tricky Day.

“I didn’t think the songs weren’t up to snuff; they were just different kinds of songs for Pete. They weren’t Won’t Get Fooled Again, which people were expecting. Pete was in a different zone at the time. He was into punk, and he was into the nightlife. I think it was a strange time for him. Recording guitars with him was fun when he was sober; he and I were buds throughout the thing.

“The rest of the band didn’t care for me at all, though. Roger and Entwistle didn’t particularly like me, and the feeling was mutual. They didn’t like being told what to do. That’s the way it goes. You win some and you lose some. But we had some hits on it. It wasn’t a complete failure. I loved The Who – they were idols of mine – so when the chance came up to work with them, I couldn’t say no. I just don’t think I did a great job. It happens.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.