When Nathan Chapman won the Album Of The Year Grammy Award in 2010 for co-producing Taylor Swift's multi-platinum disc Fearless, he viewed the accolade not only as an honor but also a sign that it was time to keep pushing.

"It was cool to have something like that happen early in my career," Chapman says. "It let me see how high the bar is. But winning the Grammy didn't take away my dreams; it gave me more goals to shoot for. I was like, 'OK, I'd like to do that again someday.'"

That may happen sooner than later: Chapman co-produced Swift's 2012 album, Red, which has just been nominated for both Best Country Album and Album Of The Year.

The 36-year-old Chapman began working with Swift in 2004, when he was a session guitarist playing on demos and the future star was a 14-year-old aspiring singer-songwriter. Beginning with Swift's self-titled 2006 debut, Chapman has co-produced all of artist's albums, creating a new paradigm for the sound of pop-country crossover (tight, bold guitars, fiddles and steel guitar, walloping beats and choruses that mean business) and racking up sales in the tens of millions. Along the way, he's become one of Nashville's most in-demand record makers, helming hits for The Band Perry, Shania Twain, Keith Urban, Lionel Richie and Point Of Grace, among others.

Chapman sat down with MusicRadar to talk about how he got his start, what he heard in Swift's demo tape, how he remade Endless Love with Lionel Richie and why Nashville is different from any other music town.

Your parents [Steve and Annie Chapman] are performers. Did they encourage you to get into music?

"Yeah, I was around studios a lot with my dad. He wrote all the songs for him and my mom - they were a duo. I was exposed to the songwriting process and all of that. My mom and dad went independent in 1987, which was pretty unheard of then, paying for your own records and distributing them by themselves. Because they were doing that, my dad was doing pretty much everything. He'd put me in front of different musicians and say, 'I'm writing you a check today, so my kid's gonna watch you work.' [Laughs]

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I got to hang out with Jerry McPherson, whom I'm working with now, actually; Don Potter, an acoustic guitar player - he co-produced a lot of The Judds' records; and Gary Hedden, who's kind of an engineer's engineer. It was great being around everybody and watching them work."

By being a fly on the wall at such a young age, did that helped shape your production aesthetic?

"You know, a lot of kids nowadays have Logic and a laptop, and they're able to dive into the process of recording music and putting their ideas down. The early impressions that were made on me as a kid were more on the philosophical side, because I had no idea what all the knobs meant. Watching these records being made, the process seemed so unattainable; it was tape and consoles and plate reverbs and all that old-school stuff. As a kid, there was no way I'd be allowed to play with Don Potter's rig, you know? In my late teens, my parents bought me some studio gear, but like I said, my early impressions were more philosophical and creative."

"Some producers are like, 'Here's the song and here's the production,'" Chapman says. "With me, it's just 'Here's the song.'"

Can you elaborate on that? What did you come away with that you were able to apply to your own work?

"Well, when I was 12 years old, Don Potter looked at me and said, 'Don't ever have a song that doesn't have an instrumental hook. It should be different from the rest of the song, but it's gotta be memorable.' You're 12 years old and Don Potter tells you that, that sticks. I remember Gary Hedden was mixing a song, and there was a percussion track that was a little bit out of time. He said to me, 'You know what you do with something that's not grooving? You turn it up!' [Laughs] Little things like that.

"Watching my dad, too, seeing him make records - it all rubbed off on me. The guys were all open and honest with me. I was the artist's kid, so they'd tell me all their tricks and stuff."

Did you have a plan B, or were you always set on working in music?

"I'd say there was no plan B. Growing up around music, it was just everywhere. I was inundated with it, and I loved it. There was no way around it for me, and I'm grateful for that."

Who were your early guitar heroes? Who did you want to emulate?

"I had three or four guitar heroes: Phil Keaggy, David Gilmour, and Dana Key from the Christian band DeGarmo and Key. Dana was a Memphis guy, blues based - he passed away a few years ago. I was way into blues players. David Gilmour's a blues player, and so was Stevie Ray Vaughan. Phil Keaggy can be more avant-garde, super-smart rock 'n' roll. Those were my main guitar heroes growing up."

Did you start out doing sessions as a guitarist before you got into production?

"I worked a lot in studios as a kid, but I got away from it when I went to college - I kind of needed a break. When I came back, I figured out that I could do demos really well for songwriters. My wife is a songwriter, and she was writing at the same company where Liz Rose was writing - Liz and Taylor wrote a lot of the early hits together. I became something of a demo guy for a lot of songwriters. When Taylor and I started working together, she was just 14, and she was just another songwriter in my world of doing demos."

"She's a great storyteller," Chapman says of Swift. "All of the iconic artists in Nashville tell the best stories." © Devin Simmons/AdMedia/Corbis

What stuck out to you about her, though? She was very young, but obviously something seemed different about her.

"I thought her songwriting was brilliant, and I was around the best writers I could be at that time as a producer. I was around Liz Rose, my wife Stephanie Chapman, Lori McKenna, Brandy Clark. The group of songwriters I was doing demos for was just incredible.

"Taylor was already amazing. One of her big hits off the first album is called Our Song, which she wrote by herself. If you break down that chorus lyric - 'Our song is a slamming screen door, sneakin' out late, tapping on your window' - it's, like, all of these sounds of the relationship are the song. That's super-smart, brilliant stuff. As a young producer wanting to work on the best songs I could get my hands on, I was like, 'I got it.' That was the first thing that hit me about Taylor, the songwriting."

Being that you're a guitar player, when it came time to produce Taylor, what did you envision for the actual guitar sound on the records?

"A lot of times producers tend to take what a songwriter wrote and make it different because they think it needs to be different. Some producers are like, 'Here's the song and here's the production.' With me, it's just 'Here's the song.' I wanted the production to disappear into her vision of what the song should be.

"I just thought Taylor's songs needed to be bigger. The idea was to keep the heart and soul of the songs, make them bigger - adding drums and bass and overdubs, percussion and harmonies - but not make them different. I think the sound of those first two or three records we did together is the heart and soul of what she wrote, and it's the bigger version of what she sang to me, just her and her guitar. It's what I heard in my head, but I tried to not make it different from what she felt like when she was writing."

Now, you've undoubtedly taught Taylor a thing or two during your time together, but I'm curious - what has she taught you?

"How to write a song, pretty much. But one of the biggest things was something pretty interesting: When we made Speak Now, there were several five- and six-minute songs on the project. At one point, that felt like a tall order, because you don't want the listeners to feel like they're listening to a long song. But when I saw her at rehearsal, and I saw how she built the show with these songs, I was like, 'Ohhh, I get it now.' She had this show in her head when she wrote the songs; she had a vision."

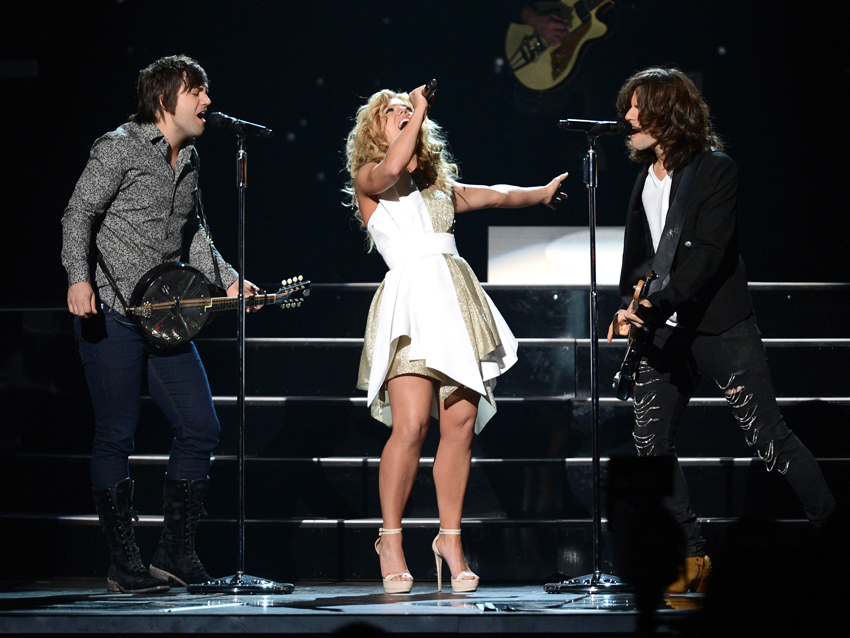

"We really took our time and made a pretty special record," Chapman says of working with The Band Perry (from left: Neil Perry, Kimberly Perry and Reid Perry). © Laura Farr/AdMedia/AdMedia/Corbis

You co-produced The Band Perry's first album. How did you hook up with them?

"Through [Big Machine Records CEO] Scott Borchetta - they're on the same label as Taylor. They needed somebody to cut five songs on the record. I had a blast in the studio with them. Chuck Ainlay engineered it, and he did an awesome job."

Did you have a particular agenda when you went into the studio with them? Anything you wanted to do or not do with them?

"I wanted the guys in the band, Neil and Reid, to play on the tracks in the studio. That was a little out of the ordinary, because sometimes bands don't play on their records. But I definitely wanted them to be on the tracking dates. It's way cooler like that than if it were only a bunch of studio guys. And the studio guys are great; sometimes they're so good, you feel as though they are the band as opposed to studio players. I had a great time with them. We really took our time and made a pretty special record."

Sometimes band members get intimidated and uncomfortable with session guys on their dates. How did you help to create a good environment for everybody?

"The studio guys I had - Shannon Forrest on drums and Brian Sutton, who played acoustic guitar - they're really cool guys who don't give off a superior vibe. Brian, especially, is one of the who's who of acoustic guitars. So with the guys in the band, it's kind of like they got to play with their heroes - they were more excited than nervous. Rather than being intimidated, I think they were inspired.

"The vibe in Nashville is different from other places. You might intimidate somebody by accident, but you wouldn't do it on purpose. People don't carry themselves in that way. If you were the kind of person who tried to make others feel 'less than,' you probably wouldn't get called that much. It's a real family town."

How did you come to work with Shania Twain? In 2011, the first new music she made in six years was with you.

"What happened was, I got a call from [producer] Tony Brown, who was working with Lionel Richie. Lionel wanted to do some tracks that were programmed, where you built it from fake drums up, and then you go in and cut it with the band. Tony is a very generous and dear soul, and a really great guy, and he told Lionel, 'If you have a few songs you want done that way, why not hand them over to Nathan? He works like that.'

"Lionel and I had dinner, and he told me that he wanted me to work on a version of Endless Love that he wanted to do with Shania Twain. He said, 'Build a track and let me see what you would do on a 2012 version of the song.' I gave it a shot, and a lot of what you hear on the Tuskegee record for that song is what I built at the house. Then Lionel sent that track with his vocal to Shania. She loved it and said, 'Great, let's cut the vocals.' We got together and cut her vocal, and after that she said, 'Hey, I've got this other song. I want you to work on it for my TV show.' And onward we went, doing the song Today Is Your Day."

Actually, I wanted to ask you about Endless Love. What were your ideas for updating it musically? That can sometimes be a tricky thing - you don't want to take it too far so people don't recognize it, but you don't want to Xerox the original, either.

"Yeah, that's true. What happened was, I had bought a ukulele for a Colbie Caillat song I worked on. For some reason, I couldn't put it down, and when I started thinking about what to do with Endless Love I started playing it ukulele. It was kind of an 'aha moment" where I was like, 'Oh, hey, this would be pretty cool.' That's where the arrangement came from, walking around the house playing it on ukulele.

"When Lionel came over, I looked at him and said, 'I've got one word for you, Lionel: ukulele.' He gave me the funniest look, but when I hit play on the pre-production he was like, 'Yes. This is awesome!' That's the same ukulele I play on Keith Urban's single Little Bit Of Everything. It's a Collings Koa wood - sounds incredible."

What's your favorite studio in Nashville?

"Blackbird. Blackbird D is my favorite tracking room, and E and H are my favorite overdub rooms. Fabulous studio. Trying to say everything that's good about the place would take forever. The rooms are very versatile - you can make the A and the D rooms gigantic or very small and '70s dry. And the gear, with [studio owner] John McBride, you have every type of compressor, preamp, mic or tape machine ever made. There's no limitations for the kinds of equipment you might want.

"The assistants - everybody from the runners to the assistant engineers - are all top notch. It's a dream gig to work there, so they're able to hire the best. They know everything about having a studio. Plus, John and Martina McBride are just the sweetest people. They're the kinds of people you want to be friends with. It's a great hang and a terrific work experience. The first time you work there, you go, 'Oh, there are other studios? I forgot.'" [Laughs]

Do you want to stay pretty much in the country genre? Would you want to produce any straight-up rock bands - or metal bands even?

"Well, I have been doing some tracks with O.A.R. They've had a bunch of hits, so it's cool working with them. I did the Keith Urban singles that were out earlier this year and the Lady Antebellum single. I like staying in Nashville and working here. If I did a heavy metal record, it would be a disaster. Banjo and steel guitar would end up on it somewhere." [Laughs]

Nashville is the hottest music town on the planet. Why do you think it's special - or different - from other major cities right now?

"I grew up here, so I'm probably biased. [Laughs] For me, I like to make music with the story first, and that's the big thing about Nashville: It's a story town. I look at it the same way as if you were making a movie. If you have a great story, you're starting off with a tremendous advantage. Nashville celebrates storytelling.

"That might be why some artists who come here struggle to have a hit in the country market. It looks easy from the outside, but it's not. All of the iconic artists in Nashville tell the best stories. Willie Nelson, Reba McIntire, Dolly Parton - so many others I could name - they all have that in common. That's one of the reasons why Taylor has done so well and why she calls Nashville home: She's a great storyteller."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

“The thing from the agency said, ‘We want a piece of music that is inspiring, universal, blah-blah, da-da-da...' and at the bottom it said 'and it must be 3 & 1/4 seconds long’“: Brian Eno’s Windows 95 start-up sound added to the US Library of Congress