Producer Mike Fraser's 10 career defining records

Not many former janitors get to tell Jimmy Page to redo a guitar part, but that’s exactly what Mike Fraser did.

The engineer, mixer and producer worked his way up from cleaning the floors at Vancouver’s Little Mountain Sound Studios to being one of the industry’s A-list studio wizards, working with the some of the biggest names out there along the way.

“We were recording the Coverdale/Page album, and Jimmy laid down a guitar part that was fine,” says Fraser. “The only thing was, the way he played the part before was way better.

"So I thought for a second, ran the words through my head, got on the mic and said, ‘Um, that was really good, Jimmy, but I kind of liked the way you played it earlier.’"

So how did the Led Zep legend respond to his request?

“He was really cool. He said, ‘Oh, well, that’s no problem. I can just do it the other way if you think it was better.’”

Over the years, the Canadian-born Fraser, whose big break came when he was able to put down the broom and assist Bob Rock on sessions, has had a hand in a trainload of gold, platinum and multi-platinum releases by rock’s elite: from AC/DC to Metallica to Aerosmith to Joe Satriani, they’ve all come to rely on what Fraser likes to call “an honest, no b.s., friendly approach to making music.

“I like high energy and a sense of realness,” he continues. “I want to hear a band play me a song and sound like they really mean it. I think that’s what audiences want, too. Pure raw emotion is always the ticket. So it’s my job to go in there and capture that magic moment.”

That same philosophy holds true for mixing: “If the heart and soul of the performances are on the tape, I have to preserve those elements. Sure, there are times when I might do some edits and throw on some effects, but only if they enhance what’s already there and what’s great. I should be invisible. It’s all about the artist and the songs.”

Fraser, who favors Neve or API boards for recording (“nice warm punch”) and SSL consoles for mixing (“very crisp clarity, amazing automation”), says that he still feels like he’s living out a dream when he walks into the studio and finds himself face-to-face with one of his heroes. “But you have to say to yourself, I’ve worked for this. I deserve to be here. And then you prove it all over again.”

Read on as Mike Fraser talks us through 10 of the most important and memorable albums of his career...

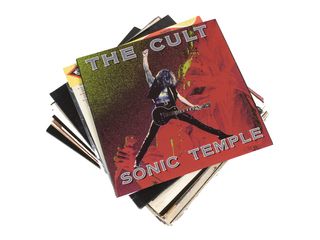

The Cult - Sonic Temple (1989)

“Bob Rock produced this album. I’d always been a fan of The Cult. To me, they're such a kick-ass rock band. When Bob told me we’d be working with The Cult, I was like, ‘Yes! A dream come true.’

“Ian Astbury is an amazing singer. He’s somewhat of a cross between a punk rocker and a commercial rock artist, whereas Billy Duffy is all commercial. He knows how to write big riffs and strong choruses. The two of them are like a collision of cultures, but somehow they pull it off.

“From a sound perspective, the band wanted the album to have a bit of an alternative vibe, but they still wanted a big rock record that could be played on the radio. My job was to capture a wide sonic spectrum so that the guys could choose whatever felt right. It had to have a full bottom end but be airy and crispy at the top.

“Billy is pretty famous for his Gretsches, but on this album he was a big Gibson guy. There were a few Strats for some other sounds and fills, but the majority of the record was Les Pauls.”

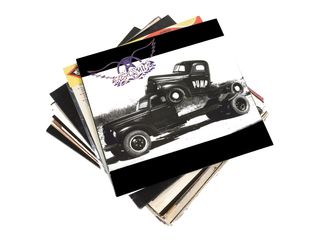

Aerosmith - Pump (1989)

“It was great to work with Aerosmith after the success of Permanent Vacation, which was the first time I got a real shot at mixing.

"Permanent Vacation was the band's comeback record, and this was the one that would really put them back to where they were in the ‘70s.

“Joe Perry and Steven Tyler had both been sober for a couple of years now, and they were really on point with their songwriting. They co-wrote a few songs with people like Jim Vallance and Diane Warren.

"But the amazing thing about Joe and Steve is, no matter who they write with, the songs always sound like Aerosmith.

“As good as Permanent Vacation was, Pump is an even stronger record, in my opinion. It’s tougher and all the juice is there. The fun thing for me was working with the guys on all the little segues between the songs.

"Everything was played live. Joe and Steve got all of these interesting instruments like didgeridoos and various pieces of percussion – that was very cool working with them on those sounds.”

AC/DC - The Razor's Edge (1990)

“Bruce Fairbairn produced this one, but he wasn’t supposed to be the producer. What happened was, George Young produced most of it, but he got ill and couldn’t finish. So the band decided to have Bruce and me take it from there.

“Brian Johnson came in to do his vocals, but he was having a tough time because of some of the keys the songs were in. We ended up lowering the keys, which then resulted in Angus and Malcolm [Young] coming in to redo guitar parts. Before I knew it, we were recording songs all over again except for the drum tracks.

“We also did two new songs, which sort of solidified things between me and the band. They were very pleased at the sound I was getting them.

"Mixing AC/DC was pretty fun because I didn’t have to second-guess what they were supposed to sound like: they were supposed to sound like AC/DC.

“When tracking, Angus and Malcolm came in, plugged in and got their sound. Angus always used two or three different Marshall heads.

"For rhythms, he liked a 100-watt Superlead Plexi head, and for leads he used a 45-watt head a lot. Malcolm had a Marshall, but it was a bass head. His guitar was super clean, but because it was going through the bass head it really delivered amazing low-end.”

Coverdale/Page - Coverdale/Page (1993)

“I had been an assistant engineer on the big Whitesnake album that Mike Stone produced. David Coverdale was very happy with what I did on that, so when it came time for him to do the record with Jimmy Page I got the call to work on it.

“Meeting Jimmy Page…wow! You try to be cool in all of these situations, but come on, this is Jimmy Page! It was pretty unreal. And what a great guy he turned out to be.

"Very friendly, very collaborative. I mean, he knows what he wants, and he really doesn’t need anybody to help him make records. But there are times when he does want second opinions, and he’s open to them.

“Working with Jimmy was definitely a learning experience. He knows so much about amps and miking. One day I had put a mic near the center of an amp, and he said, ‘Why don’t you try putting the mic off to the side? That way you don’t get the attack sound, but you still get all the fullness.’ And he was right.

“I got an even bigger lesson on another day. He had recorded about six or seven acoustic parts to a song, all of these layers. Then he went home. I stayed behind and listened to the takes. I thought some of them were a little untidy, so I cleaned them up a bit. Nothing major, but a little fixing here and there.

“Jimmy came back the next day and listened. ‘What happened to my guitar parts?’ he said. ‘Oh, I just cleaned them up a bit,’ I said. ‘Well, put them back the way they were,’ he said. ‘They’re supposed to sound that way.’ And he was right again. What I thought was a little off wound up having the energy and the feel that only comes from Jimmy Page.”

AC/DC - Ballbreaker (1995)

“I co-produced this album with Rick Rubin, which was interesting. Rick’s definitely one of the most unique people going.

"He knows music, knows what an artist should do. He doesn’t always say a lot, but whenever he does, he’s right on the money.

“We started the record in New York, but we didn’t like the sound of the studio. No matter what we tried, nothing felt right. So we all wound up in LA at Ocean Way Studios – things sounded a lot better there.

“Rick is a pretty hands-off guy. He doesn’t like to interfere with a band’s creativity, so what he does is, he’ll come in later in the day and listen to something that’s been recorded.

"If something isn’t to his liking, he’ll say, ‘Mmm…that’s not right. We need to fix that.’ He won’t always say what isn’t right – he just knows when it’s not there yet.”

Metallica - Load (1996)

“This record was pretty much finished by the time I started mixing it. Actually, I mixed half of it. Randy Staub did the other half.

"The reason for this was because the band wanted to take a lot of time in the mixing stage, so I’d spend six days on one song, and Randy would be doing another song in six days. A lot faster than having one guy work for 12 days on a song.

“I mixed at Quad Studios in New York while Randy was mixing at another studio nearby. As this was all going on, the band was still doing some recording.

"So they’d finish doing what they were doing, go to Randy’s studio, hear what he did, then they’d come to see me and listen to what I had. Sometimes they’d like more what I was doing, and vice versa.

“Originally, Load was supposed to be a double album, but because so much was happening at once it was decided to split them and release Load and then ReLoad a year later.

“I know Lars and James have butted heads a lot, but for mixing they’re a pretty unified team. On these records, Lars was the louder of the two, though.

"There was one point where he wanted to bring the drums up more and more, and I said to him, ‘I can’t – the board is maxed out.’ So he said, ‘Well, just plug something else in then.’ He knows what he wants, and he doesn’t let go till he gets it.”

Metallica - ReLoad (1997)

“Even though most of everything had been recorded a year previously, we waited until Load had been out there for a while until we came back to the other material that made up ReLoad.

“Again, it was Randy Staub and me, each taking five or six days to mix one song. It’s funny: to this day, neither one of us is entirely sure who did which track.

"We have similar philosophies when it comes to sound, and we’ve both worked with Bob Rock a lot. It wasn’t like two polar opposite guys on one project.

“The process was almost exactly the same as it had been for Load: James was recording and rerecording some vocals at one studio, and then he and Lars would bounce back and forth between Randy and me. A year later and nothing had changed. Lars was still telling me to turn up the drums!”

Slipknot - Iowa (2001)

“Ross Robinson produced this album. Working with Slipknot was amazing. They’re such a high-energy metal band. Up to this point, it was probably the most metal thing I’d ever done.

“The first day of tracking, Ross and I went into the studio and saw that the drums were set up in this big drum room. Ross said, ‘No, that’s not going to work. I want the drums to sound nice and tight.’

"We tried a few different combinations of putting the drums into these gazebos and assembling baffles around them, but Ross wanted the band to be right there playing with Joey Jordison.

“We ended up moving the drums into this little hallway and the band kind of crammed their way in there all around Joey. We had the amps in an iso booth.

"It was amazing. Here we are in this giant studio, and this big, big band is packed into a hallway. We called it ‘the Sweat Box.’

“When you record a band like Slipknot, who play live in the studio and make such a huge sound, it’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle.

"You can’t have too much bottom end because things will mush together. Matching the bass to the kick drum is pretty important – and Slipknot like a pretty clicky kick sound. The guitars can’t be too thin, ether, because they’ll get lost.

“Finding that right sonic point can be a challenge in cases like this, but the minute you find it, you’re there.”

Joe Satriani - Black Swans And Wormhole Wizards (2010)

“Joe and I have done a few records together. For the Black Swans album, he wanted to assemble a band that he would then tour with.

"I don’t know if he felt this way because of the success of Chickenfoot, but I thought it was a great idea.

“We set up at Skywalker Sound in California, and I could tell right off that there was going to be a different vibe to this album than on some of his other ones.

"Having a keyboard player, Mike Keneally, allowed Joe to weave the melodies in a new way. He still played like crazy, but he didn’t have to fill up every measure of the music.

“My role with Joe is to get him the sound he wants and allow him to explore his creativity as far as he can go. He’s got the songs pretty worked out before we get in the studio, so I never really have to give him input on arrangements.

"There’s only a few times where I might say, ‘This section goes on a bit long, how about we get back to the riff a little faster?’

“It can be hard for an instrumental artist to tell different stories album to album, but this one was a real giant step forward for Joe. It’s darker in some ways, but I think it was great to see him get inside some of those emotional areas.

“He had a few kinds of amps with him, but overall, the main sound on the record was from his Marshalls. They really delivered a wide array of tones.”

Chickenfoot - Chickenfoot III

“I mixed the debut album, and when it was time to do the follow-up, I came back to do the whole thing.

"The guys in Chickenfoot are fantastic. They’re all very accomplished in their own right, and then to have them come together to work on the same record, it’s pretty remarkable. And they do it with no egos, too.

“Sammy [Hagar] is a great energy guy. He’s probably the most positive person I’ve ever met. Sometimes I did have to push him a bit, though, because he’d come in, sing a vocal and go, ‘All right, that sounded terrific!’

"And I’d have to say, ‘Yeah…but I think it can be better. How about you do it again tomorrow?’ He’d look at me kind of funny, but then he'd realize that he probably did have a better take in him.

“I’m pretty proud of the finished record. You can hear that there’s more depth to the lyrics, and because the band did so much touring, they sound tighter.

"Sonically, it punches more, it’s more polished, but the live feel is definitely there – nothing’s edited together with these guys.

“Joe is marvelous when it comes to guitar sounds and textures. He had an amazing Marshall amp. It might have been a prototype, I'm not sure. From clean to mid-crunchy and then to complete overdrive, it did it all.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

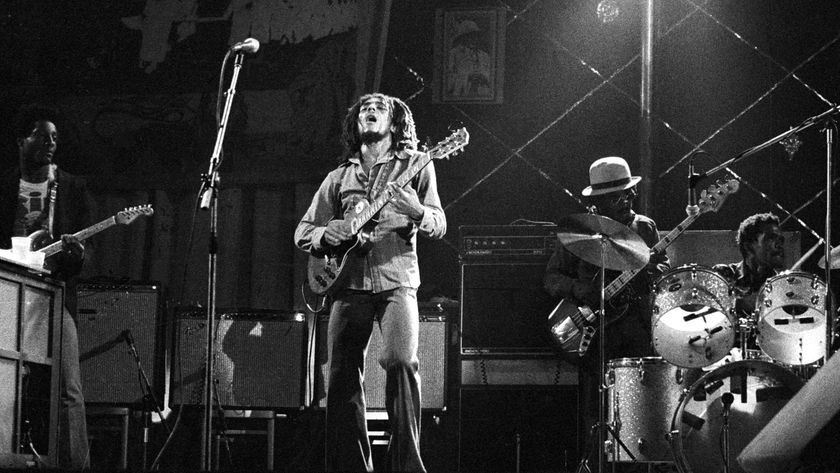

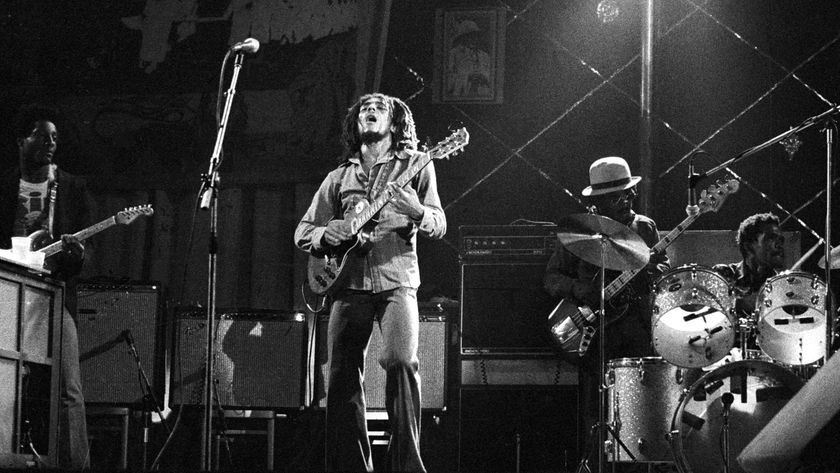

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)