The upcoming album ...Ya Know? is a posthumous triumph for singer Joey Ramone. © Janet Macoska

"He was a sweet, lovable guy," says producer Ed Stasium about Joey Ramone. "He was down-to-earth, hard-working and always treated everybody great. He was like that from the day I met him to the last time I saw him. Joey never changed."

Stasium first became acquainted with Joey Ramone and the rest of the iconic punk rock quartet known as the Ramones in the winter of 1976, and over the next half-decade, as both an engineer and producer, he helped guide the band through a blistering series of releases that include such groundbreaking works as Leave Home, Rocket To Russia and Road To Ruin.

"It was a pretty incredible time," Stasium says. "Did we know we were making history and that people would be listening to those albums 30, almost 40 years later? No way. We were just trying to get things done as fast as we could."

And now, 36 years after they met, Stasium and Joey Ramone are reunited on the upcoming album ...Ya Know? (the title refers to one of Joey's much-used conversational phrases) in what amounts to a smashing, belated follow-up to the late singer's first solo record, Don't Worry About Me, which was released a year after his death in 2001. (You can check out the song What Did I Do To Deserve You? on page two.)

Working with Ramone's brother, Mickey Leigh, and manager, Dave Frey, Stasium produced 10 of the album's 15 tracks, utilizing four-track demos that Joey was recording in the months before his death and breathing new life into them with the help of an array of talents who all have a connection to the punk legend: Joan Jett, Little Steven Van Zandt, Richie Ramone, Bun E. Carlos, Dennis Diken (from the Smithereens), and others.

We caught up with Stasium recently to talk about the recording process of ...Ya Know? In addition, the veteran producer shared his memories of crafting the Ramones sound in the '70s, along with his reflections on being in the studio with Phil Spector for the album End Of The Century.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You and Joey spoke regularly in the years before his death. Were you talking about doing a record together?

"We talked about it, sure. I had moved to California, and he was in New York, but we always kept in touch. We spoke on the phone a couple of time a month. When he did come out to the coast, we'd always get together. I'd grill up a meal for us.

"He was doing OK for a while. I wasn't able to see him in his final months or weeks. I hadn't even spoken to him probably in six months at that point - he got really sick. But until the last six months, he was fine. He was working with his band, The Independents. I remember he called me right after he had been diagnosed with lymphoma. He said, 'Eddie, right after my fuckin' band breaks up, I get cancer!' Those were his words to me."

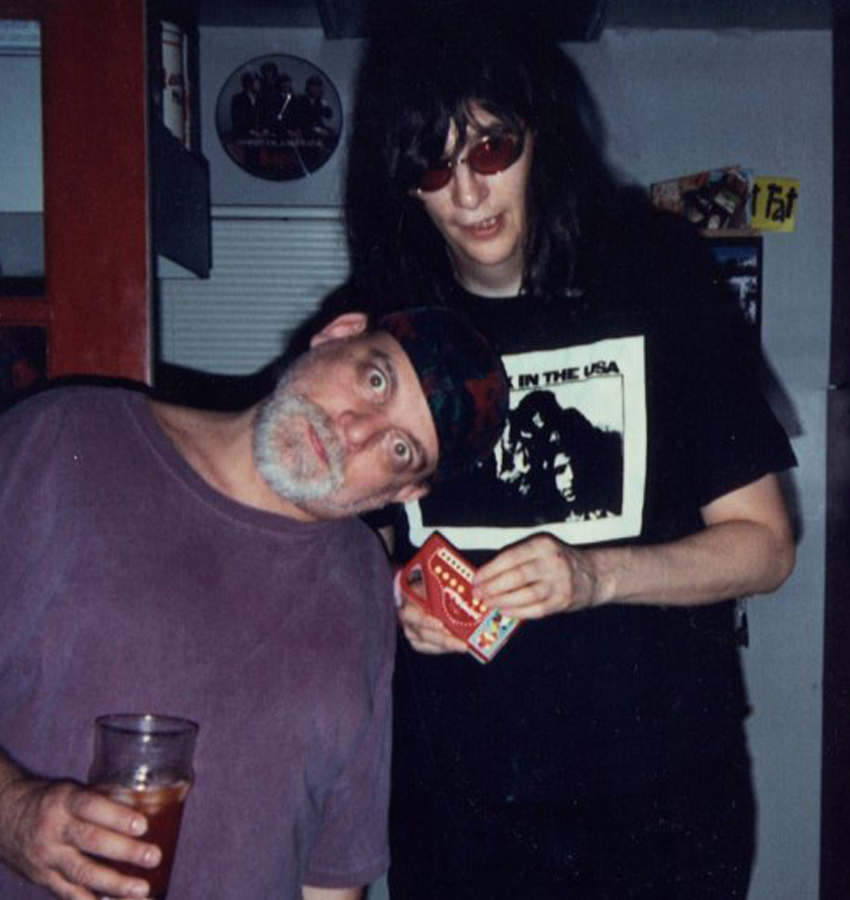

Stasium with Joey at the producer's Los Angeles home in 1997. © Joanee Tarshis

What shape were the demos in when you got them?

"They weren't bad, for the most part. Some of them were recorded on Fostex machines. Joey was working with Daniel Rey at the time, so Daniel updated the demos a little bit before I got them. I was first made aware of the tapes around in 2006, and I acquired them in 2008.

"Mickey, Dave Frey and I agreed that we would only listen to Joey's vocals. Things were pretty basic - there was a drum machine, a guitar, a bass and Joey. The drum machine wasn't programmed or anything; it just made a beat. Some of the songs were fragmented, and some were arranged very well. That's what I had to work with."

Above: listen to the song What Did I Do To Deserve You?

The songs that were fragmented, what did you do to them to flesh them out?

"I tried to add what I thought Joey was going for. I made solos where there weren't solos, intros where there weren't intros, endings where there weren't endings. I was fortunate that the original recordings had a drum machine on them. Even on a Fostex cassette recorder, it held up pretty well.

"I bumped all the stuff up to Pro Tools, and from there I worked with the drum machine and the vocals. On Pro Tools, there's a function called Identify Beat, and I went through the drum machine and vocal tracks and I literally identified each beat. It was… tedious! [laughs] But that enabled me to make a grid and fly stuff around. So if there were three choruses and one vocal all the way through, I could take those three chorus vocals, line them up, and pick and choose."

Joey's vocal performances were good on the demos?

"Oh, absolutely. Joey did good vocals. Those were pretty much all we kept from the original recordings. But, as I said, I augmented them. I moved them around a little bit, double-tracked them where I could… There were some spots where Joey would sing with himself and do harmonies.

"At this point in his career, he was growing. He was always a great singer. He could nail a one-take vocal, no problem. He did his voice exercises, paid attention to how he sang. The guy was spot-on with his pitch - no correction necessary."

How did you go about picking the other players on the record? Was everybody a friend of Joey's?

"Yeah, they were all buddies. That was the original intention, to get his friends together and be on the record with him. I laid out the blueprints for everything. After I did the Identify Beat thing, I put down the guitar, listened to it, made an arrangement and got the parts together. As it turned out, we used most of my guitar and bass parts on the record. But we needed individual personalities, and that's when the other folks came in.

"I'm certainly no drummer, so we got some real players. We knew that Richie would be great, and Bun E. wanted to play on it. Thunderbolt [JP "Thunderbolt" Patterson] is a tremendous drummer, and he knew Joey, so he did a couple of things. And Dennis Diken came on, as well. We mixed them up. Everybody did a fabulous job."

The Ramones (from left, Johnny, Tommy, Joey and Dee Dee) onstage at New York's CGBG, 1977. © Hiroyuki Matsumoto/amanaimages/Corbis

Was it strange to work on the tracks without Joey being around to hear what you were doing?

"No, not at all. You know, I worked with the Ramones on 10 or 11 records. Plus, Joey was a good friend of mine, so like I said, I knew what he would want. Honestly, I can say that I felt his presence throughout the entire project."

How did Joey write songs? Did writing come easily to him?

"I was never around him when he wrote, so I couldn't say. Anytime I got involved with him for an album, the songs were already done. But he did carry his one-string acoustic guitar around. Back in the day, when we were doing End Of The Century, he played me a couple of things on that guitar. 'Hey Ed, what do you think of this?' But the songs were already written."

What did the Ramones want from you in the studio? In '76, '77, what were some of the aspects of production that were important to them?

"Well, of course, I started with them as an engineer, and order of the day was 'get it done fast.' We did the tracks in two or three days. The first album - that was amazing, just blazing stuff. But the band really wanted a hit, all of them - they wanted a hit bad. So by the third album, Rocket To Russia, we started doing more overdubs, almost to soften the sound a little bit. I remember references to Steve Miller being made when we did a few of those songs.

By the time of Road To Ruin, they wanted to expand. I had done a few records with them as an engineer, and then Tommy left the band to work with them as a producer. So he and I worked on the stuff together. Johnny wanted more stuff on the record, more 'pixie dust,' as it was called, but he didn't want to bother with it himself. He was a specialist on the guitar; he did what he did. So I played some guitar on the records."

Did you ever worry that adding more 'pixie dust' to the records was de-fanging what so many people loved about the Ramones?

"I think Tommy was concerned about that. But I did give the records more of a commercial edge. We wanted to keep the punch, but we wanted them to sound like big records. We snuck as much on as we could."

What was the hardest thing about getting the sound of the Ramones on tape?

"There wasn't anything hard about it. They went in and played as a unit. No matter how many overdubs we did, it all started with live tracks. I would play guitar with them a lot of the time. On End Of The Century, my guitar is part of that Phil Spector 'Wall of Sound.' Johnny used his Moserite through Marshalls, and I played my Strat and put that through Johnny's Mike Matthews Freedom amp."

Making Mondo Bizarro in 1992 (from left): Joey, Stasium's engineer/assistant Paul Hamingson, Stasium (seated), Marky Ramone, Johnny Ramone. © Chuck Pulin

What was it like working with Phil Spector?

"Well… he was eccentric, to say the least. I was a huge fan, of course. I loved all of his stuff. Next to Mitch Miller, Phil Spector was the first producer I became aware of. His records were so important to me.

"Johnny wanted me on the End Of The Century record; in fact, he insisted that I go with him. I remember meeting Phil for the first time. The Ramones and I had been in LA for a few days or a week or so rehearsing, and I got a call from Phil's assistant asking me to go meet him at Gold Star Studios, where he was working with the Paley Brothers. I walked in, totally nervous, and said hello. I could tell Phil was a little tipsy, but he was nice - incredibly nice.

"So we're in the control room, we're listening to stuff, and Phil decides he wants everybody to sing God Bless America. He wanted me how to figure it out on the guitar. Again, he'd been drinking - he had a paper cup filled with wine. At one point, Phil knocked the cup over and wine spilled all over him. There I am, I'm in the studio with Phil Spector, we're singing God Bless America, and he's spilling wine on himself! Pretty strange. [laughs]

"A couple days later, Phil came to SIR to hear the Ramones play. He had a briefcase with him, and what he did was, he sat it down in the middle of the floor, and then he sat on top of it and said to the band, 'Play!' The band went through all the songs, and Phil was totally quiet. After the last song, he said, 'That's good. We'll see you tomorrow. Bye.' And then he left."

While cutting the record, did you learn any secrets to the Wall Of Sound?

"No. I did not. No great secrets were handed down. I didn't engineer the record - that was Larry Levine. I was the musical director on this. But I do remember that Phil made us record the songs over and over and over again, and then we'd listen to them over and over and over again - hundreds of times.

"Phil liked to listen to music loud, too - really loud. It was painful. He had to work out sign language to communicate with me and the engineer because of the volume. He had all these little signals he'd do instead of talking. He was… interesting." [laughs]

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues