Precious metal: the history of Zemaitis guitars

How an unassuming London luthier built a world-renowned brand

Introduction

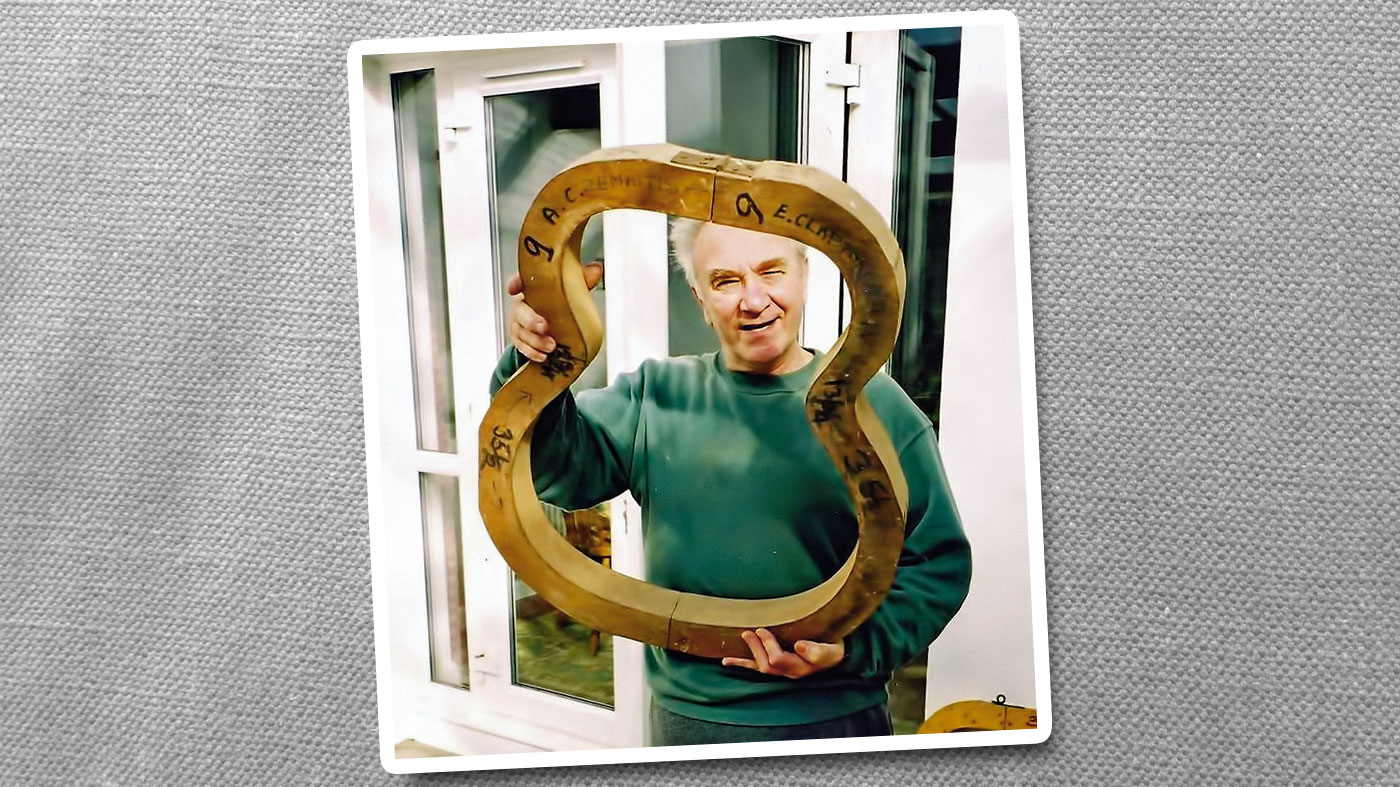

Tony Zemaitis worked alone in his own home, was unimpressed by celebrities and built only a few instruments every year.

So, why did Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood, George Harrison, Ronnie Lane and many other legendary guitarists beat a path to his door? And how did he create some of the most beautiful - and copied - guitars of all time? We explore the Zemaitis story, examining a bevy of classic original guitars in detail…

Some time around 1969, Eric Clapton popped round

“Some time around 1969, Eric Clapton popped round,” the late British luthier Tony Zemaitis once recalled in The Z Gazette, a fanzine set up by the Zemaitis Owners’ Club to celebrate his work.

“I can’t recall why, and while chatting away he picked up an early ‘test’ electric guitar and started strumming away as magic guitarists do. The uncanny thing was his playing was echoing his words and phrases as he spoke and the hairs on the back of my head stood up. It really was spooky just how the notes sounded like his voice. That stuck in my mind. You bet!”

The encounter between Zemaitis and Clapton, who was in the process of going solo following the demise of Cream, was typical of the spit-and-sawdust discussions about guitars that took place in Tony’s home in Balham, South London, which also served as a workshop.

A meeting of minds

What was different about this particular meeting was that it marked the inception of a long line of Zemaitis electrics that were to become - in their own way - almost as iconic as the top players who used them.

Lo and behold, the metal acted as a chassis and screening to all but eliminate feedback

“One of the things we talked about was a silver guitar: what would it sound like?” Tony recalled. “The short answer was… ‘God knows!’ The idea stayed with me. I was, at the time, testing to see why three-pickup, single-coil guitars never seemed to play in tune and fed back so much.

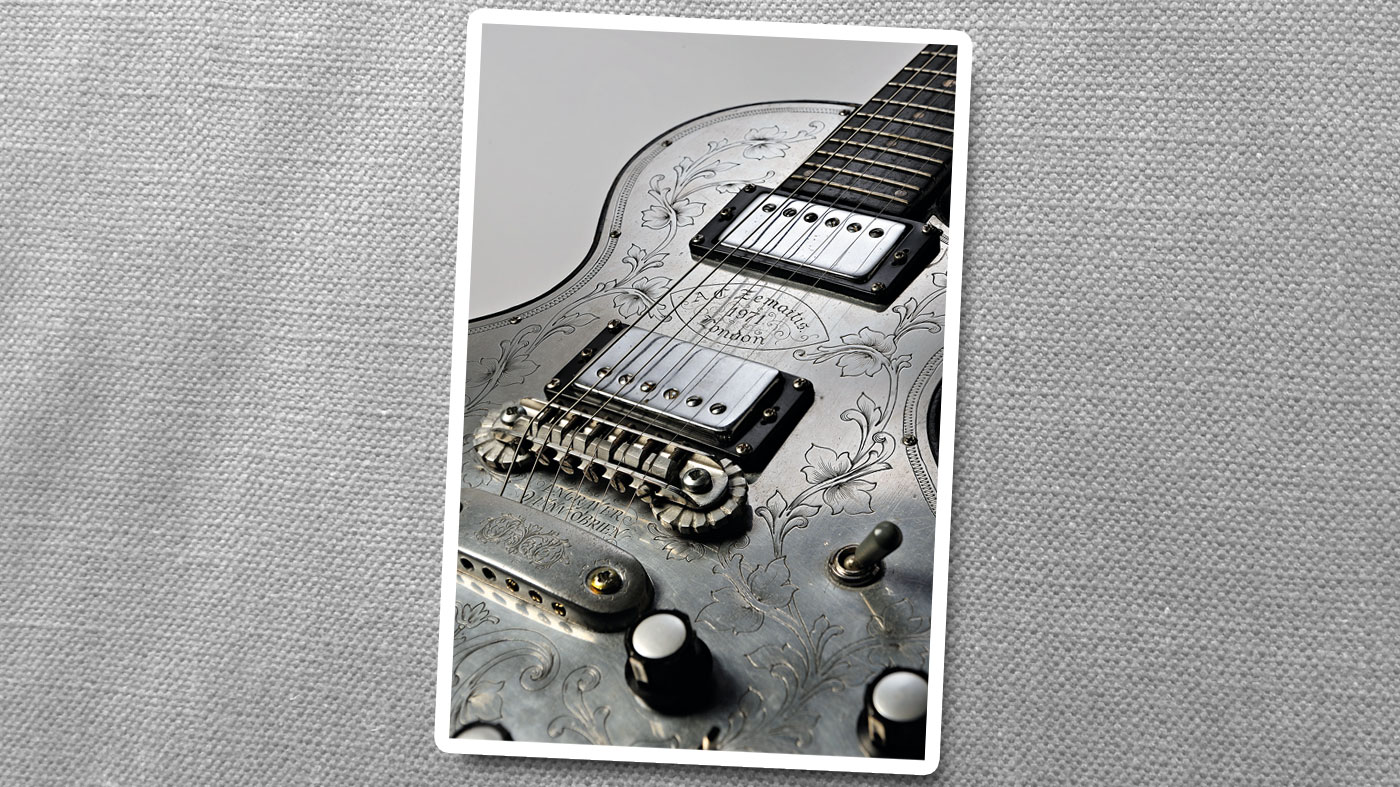

“So adding to the test guitar, to save time, I made up a metal front in plain aluminium. Lo and behold, the metal acted as a chassis and screening to all but eliminate feedback. Even the tuning/intonation seemed better. The ‘test’ guitar was sold off cheaply and then I started a proper metal-front model.”

Like many guitar innovators working from a small shop, Tony had the freedom to ask ‘Why not?’ when he hit on an idea. If he could imagine it, he could build it. And so it was with the creation of his ornate metal‑front electric guitars, which have since become some of the world’s most valuable and sought-after instruments.

“There were no ‘experts’ or schools to say what to do or not to do,” he explained. “The whole idea grew, as it went along. I asked my very good friend and engraver Danny O’Brien if he felt like doing something on the front, given a free hand. And the completed guitar looked very professional and so different.

“You just had to look at it. I hung it on the drawing-room wall and the first person to see it was Tony McPhee of the Groundhogs. A deal was struck immediately. The metal-front had arrived.”

London Calling

Tony Zemaitis was born Antanus Casimere Zemaitis in London, in 1935. Fascinated by model making as a child, he learned professional craftsmanship during a five‑year apprenticeship as a cabinet maker: exacting skills that he transferred to guitars after taking an interest in playing during the 1950s.

With the embargo on US-made guitars only just coming to a close, top players quickly sought out his guitars

His first forays into luthiery involved fixing up a damaged guitar found in his family’s attic around 1952 and he made his “first half-decent guitar”, a nylon-string classical, in 1955.

A stint in the armed forces under National Service kept Tony away from guitars - barring some repair work and gigging - until 1957, when he returned to guitar making in earnest, experimenting freely with every feature of guitar design from soundhole shapes to drone strings, and by 1960, he was selling his creations to cover the cost of the materials.

This is when word began to get out about the high standard of the guitars he was making - and with the embargo on US-made guitars only just coming to a close, top players quickly sought out his guitars.

These early acoustics found their way into the hands of everyone from Davey Graham to Hendrix, who later acquired one of Tony’s unorthodox 12-string acoustics. But at the outset, it was strictly small-time: Tony worked in the cellar of his Balham home, which, as he later commented, “was so small you couldn’t stand up straight - I was ashamed of my workshop.”

Big name customers

Nonetheless, the high-profile players kept calling and in 1965 Tony went pro, dividing his output into three grades - Standard, Superior and Custom - according to the cost of the materials and the amount of time needed to complete the guitar.

It sounded like an organ and was even taken for such…

His best-known bespoke acoustic from this period was, typically, flamboyantly unorthodox: Eric Clapton’s larger-than-jumbo Ivan The Terrible 12-string, which featured a cedar top, rosewood back and sides and a soundhole inlaid with ebony-edged amaranth hearts.

This guitar, Tony noted, “was so gigantic that I had to re-think the internal struts [bracing] into a double kite shape to artificially reduce the front area. It sounded like an organ and was even taken for such… It had 30-second sustain, later cut to 20 seconds with added inlays to the bridge, plus silver bridge pins.”

Despite potential penalties such as reduced sustain, ornate decoration was one of the reasons that famous players were drawn to Zemaitis guitars. The ‘wow’ factor ensured these guitars made a statement on stage and Tony resigned himself to the fact that this sometimes took priority over more common-sense design choices - though he did draw the line somewhere:

“Peter Green asked for seven pickups on a guitar,” he recalled. “But what he didn’t realise is that seven sets of magnets are pulling on the strings so it’ll never play in tune - if it plays at all!”

Wood and metal

Likewise, when Steve Hackett of Genesis ordered an acoustic from Tony Zemaitis in the 70s, he was advised to ease off on the ornamentation if he wanted optimum tone.

“I got my 12-string Zemaitis acoustic guitar around 1976, I think, and it’s a nice-sounding machine,” Steve recalls.

Woody [Ronnie Wood] once asked me to build him a guitar with Mickey Mouse inlays

“Tony said, ‘What do you want it to look like?’ because on other guitars he’d done these beautiful mother-of-pearl inlay things around the soundhole. I mean, they were really works of art. He’d done one for Dylan, he’d made one for Greg Lake and they looked amazing. But I said, ‘What will make it sound best?’ And he said, ‘Well, absolutely strip it back to just the basics and not have any adornment on the thing’ - so that’s why mine looks so simple.”

Not all player requests got made. “George Harrison once asked if I could make a guitar for John Lennon. Nothing unusual about that, except that he wanted one that he could climb into and play from the inside… I didn’t actually build that one.

“Woody [Ronnie Wood] once asked me to build him a guitar with Mickey Mouse inlays. I told him to go to Walt Disney and get the copyright and then I’d make it for him, but I didn’t want to do it. When those pieces come back in 10 year’s time, I don’t want to feel embarrassed at having made them.”

Tony would also be asked to do things he didn’t think were correct. Ronnie Wood wanted a bolt-on (his disc front) but he didn’t do those, like thru-necks. “I glued the neck in as usual and added a neck plate and four screws. He’d never know!”

Putting On A Front

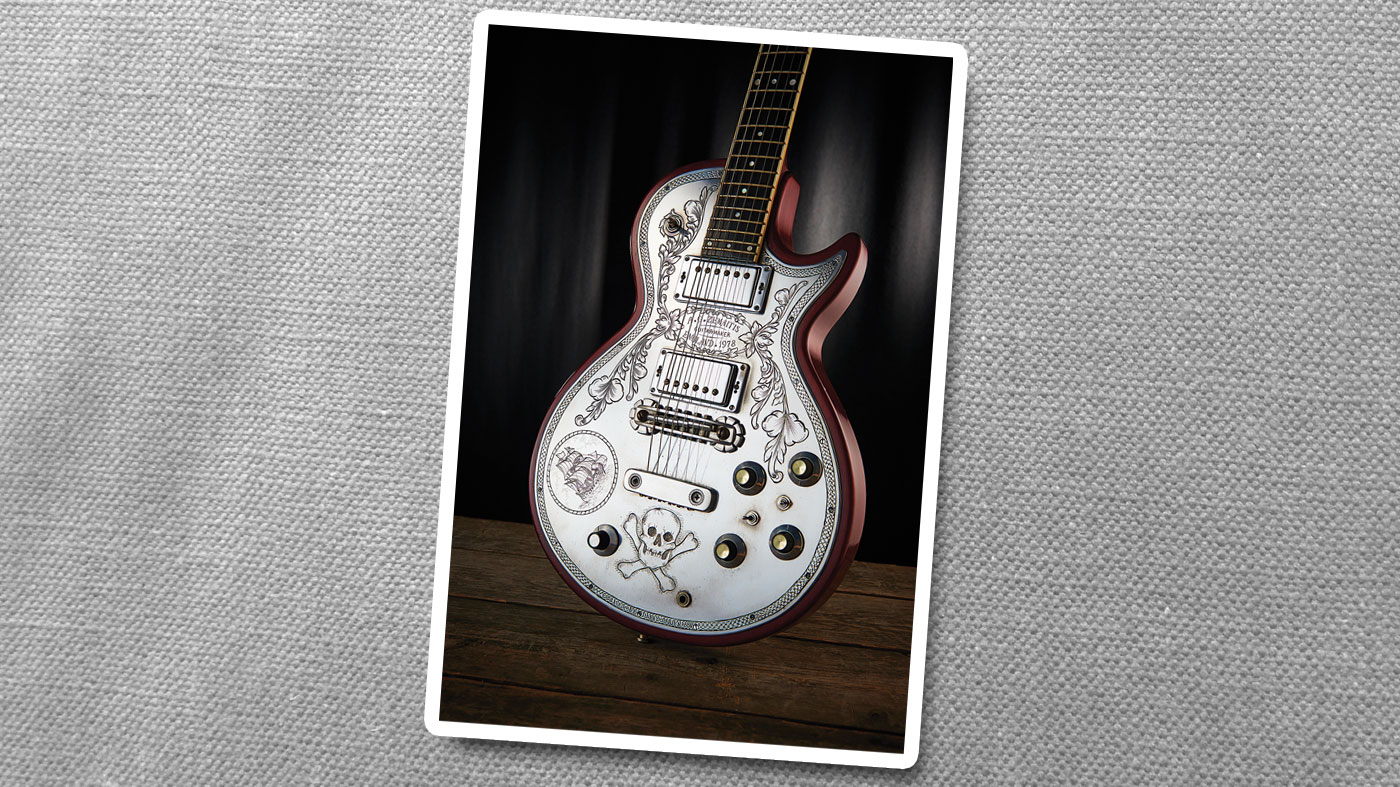

Happily, when it came to his electrics - which began appearing from 1969, Tony estimated - form and function worked in harmony. As mentioned, the engraved duralumin front screened the pickups and electronics as well as providing an ideal canvas for the engraving skills of Danny O’Brien.

The first thing Tony would do is ask you to show him your left hand. He’d determine the scale length and even the neck size

Under the ‘bonnet’, though, Zemaitis electrics were always built with three-piece bodies, which Tony felt helped “to keep the resonance very high and ‘wolf’ notes down”. These were made from well-seasoned Honduras mahogany before being carefully hand-joined using waterproof Cascamite resin glue and eventually finished with a hand-rubbed, acid-catalysed lacquer that Tony felt gave a better result than sprayed finishes.

The guitars’ set necks were also made from mahogany, a three-piece design with a harder centre section and diagonally grain-matched outer pieces, with grain diagonally aligned with that of the rest of the neck for rigidity.

The 3/16-inch stainless-steel truss rod ran through in this centre section, emerging quite high on the headstock to avoid weakening the vulnerable point beneath the nut where the neck is at its thinnest. Fingerboards were either rosewood or ebony with a compound radius and, typically, Tony’s hallmark “four-diamond cluster” motherof- pearl inlays that surround the 12th fret.

The electrics were often built with an intermediate 635mm (25-inch) scale length, though he made them longer on request as with Ronnie Wood’s disc-front, which apparently had a 650mm (25 5/8-inch) scale.

As with all things Zemaitis, however, being definitive is difficult: each guitar was bespoke and when you ordered one, the first thing Tony would do is ask you to show him your left hand. He’d determine the scale length and even the neck size - shape and decoration were up for discussion.

Big neck, big tone

In terms of pure tone, however, Tony was an advocate of chunkier necks - though not all of his customers wanted them.

“The sustain and warmth from the wood is minimal on a solidbody,” he argued. “It’s more keeping the neck still. A heavy, thicker neck is better than a light neck. But most people seem to like light necks, so you’re continually fighting what people want as opposed to what they should have!”

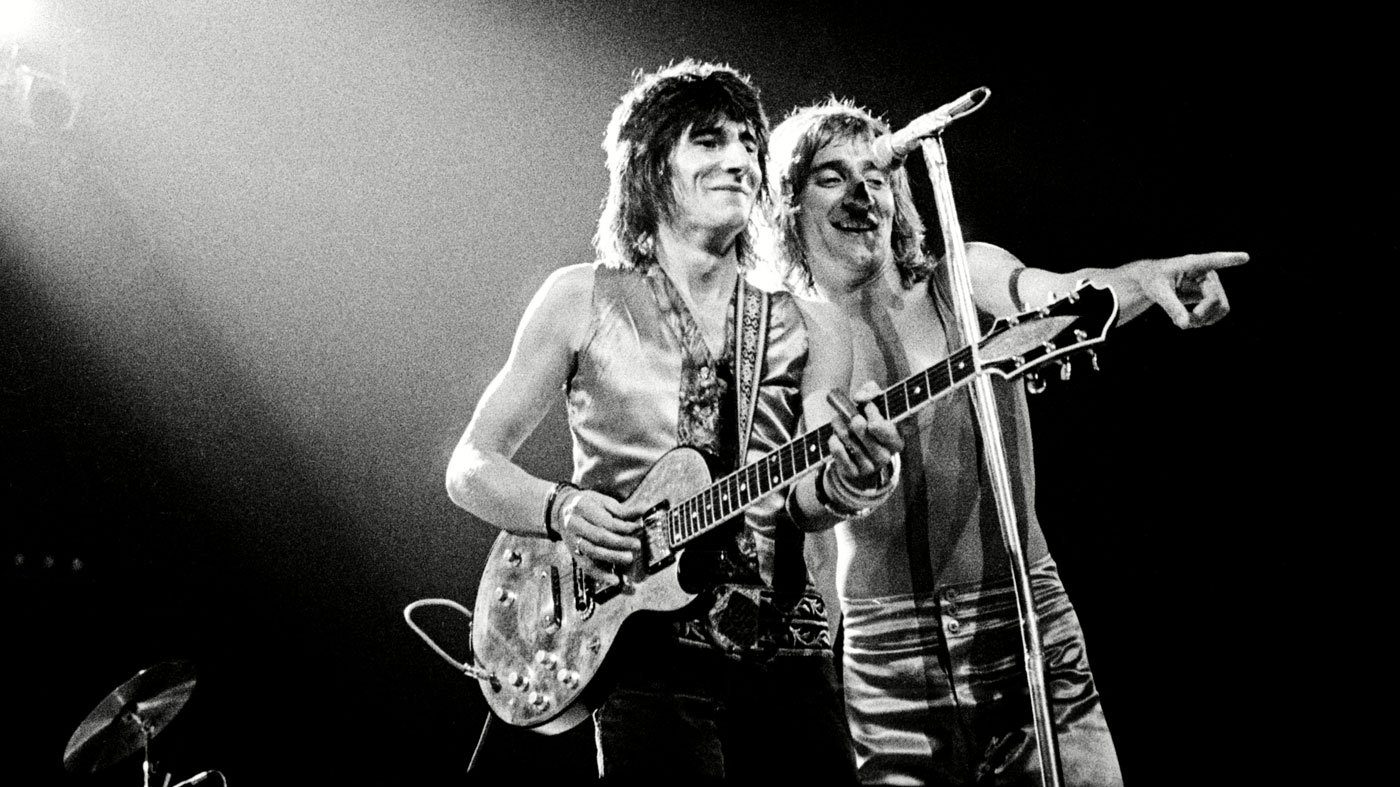

The two Ronnies [Wood and Lane] turned up. [I sold] a wall of guitars sold in 10 minutes flat, plus orders for more

Meanwhile, with an eye to where the guitars would be used, the tops of the metalfront, disc-front and inlaid-top guitars were always slightly curved, “so on stage the light dances over it, instead of flashing when it’s totally flat - like Alf Garnett’s glasses!”

Back in the 70s, pickups were far less available than they are today and Ronnie Wood, for example, would supply his own (typically Gibson humbuckers). Mighty Mite pickups (one of the first readily available retrofit brands you could buy in the UK) were often used; Kent Armstrong supplied many, too, while later customers like Rich Robinson and Gilby Clarke requested Seymour Duncans. Many earlier guitars used active preamps, although by the early 80s, Tony reflected that “pickups and amps are so good… I no longer use them unless I’m asked.”

Rich Robinson calling late at night to discuss his order - “I just wanted my Horlicks” - or Gilby Clarke turning up to his house in Kent (where Zemaitis moved to in 1972) with a film crew - “I couldn’t see what the fuss was about.”

Typical Tony-isms of his brushes with celebrities. While he was still based in South London, Tony recalled in The Z Gazette, “It was Christmas Eve (shades of Charles Dickens!). The two Ronnies [Wood and Lane] turned up. On the wall were several guitars for sale, but these were forgotten from the first 10 minutes. I honestly thought Candid Camera had turned up! Jokes, banter and leg pulling was one thing, [but] to have a wall of guitars sold in 10 minutes flat, plus orders for more, seemed too much good luck. It was true, but took hours to sink in afterwards.”

Ronnie Wood, probably the biggest unofficial Zemaitis signature artist ever, got through many Zs. “The two Ronnies threatened to bring over Rod Stewart for an acoustic 12-string, which they later did. This featured on Maggie May. They said the guitars had souls and Woody thought they would be too different for anyone to steal. If only he’d known.

“I think all he has left are the acoustic six-string, acoustic 12-string, one metal-front six-string, the black disc guitar and an acoustic bass. Even his pearly got stolen. Bad luck, Ron.”

Black Market

The engraving of the metal fronts entailed yet more painstaking hand-work, so Tony decided to add a ‘Custom Deluxe’ tier to his range of instruments, which now sat at the top of the tree - “generally the ‘popstar’ models”, said Tony.

With originals in very short supply, it was inevitable that counterfeits and copies started making their way onto the market,

This designation also covered his mosaic-like, pearl-front electrics with their more Les-Paul like top carve. No two guitars were alike, and even when the celebrity of individual Zemaitis electrics such as Ronnie Wood’s disc-front single-cut led to intense demand for exact copies from Faces and then Stones fans, Tony refused to make an identical guitar - though some bore a very close resemblance. This individuality and lack of systematic serial numbers had an unwelcome sideeffect, however. It made Zemaitis guitars easier to forge.

With original Zemaitis electrics both highly desirable and in very short supply, it was inevitable that counterfeits and copies started making their way onto the market, though Tony himself could always quickly identify fakes made by swindlers and offshore copyists.

“Copies just try to hang onto the likeness,” he wrote. “[I] can have eight companies making copies without permission… in the UK, Japan and USA. In one case, a UK company used faxes to pretend to be my agent. And by a fluke I have these to prove what I say… I was also surprised to see secondhand Zs fetching more than the new price, hence the fakes.”

In February ’92, Tony wrote that his Japanese ‘Z Club’ had told him there were “approximately 30 Zs in Japan - approximately 12 are fakes”. A year later, “some poor sod has just paid £4,100 for a dodgy pearl front ‘up North’. It’s so sad.”

The Zemaitis zenith

Ironically, too, it was the forgeries that made Tony, in mid-’93, put up his prices to match the fakes.

As the 90s progressed, interest in Zemaitis guitars grew and grew. In January ’94, Tony wrote, “just heard from a client that he’s sold two Zs for £20,000 in the UK. They were NOT top models!”

All of these factors conspired to make buying an authentic Zemaitis something that required careful scrutiny

These fakes fell into a few categories. Firstly, there were copies and clones made from scratch by both small-scale forgers in the UK and Japan and larger offshore factories. Other counterfeiters would, more subtly, take genuine wood-front Zemaitis electrics and apply fake metal or pearl fronts to them, to up the value.

Another subtle form of forgery involved building a fake guitar but fitting some genuine Zemaitis parts to it, to lend a veneer of authenticity to an otherwise obvious ringer.

The celebrity associations of Zemaitis electrics also meant that supporting provenance was often faked, too, even when the guitar was genuine. Such tricks involved selling a real Zemaitis along with false documents, claiming it had once been owned by this or that very famous guitarist, fraudulently raising its desirability and thus value.

Finally, while staying within the letter of the law, speculators would also cynically order a topspec guitar from Tony - only to sell it as soon as it was completed for more than they paid to Zemaitis himself. “My output is limited, so the ‘help yourself’ merchants moved in to prey on the innocent,” he commented, phlegmatically.

All of these factors conspired to make buying an authentic Zemaitis something that required careful scrutiny, expert knowledge and a level head - and many investors and genuine fans got burned by fakes.

With such evident demand for his guitars and so many copyists, large and small, Tony Zemaitis had begun producing simpler unadorned Student electrics in 1980 to try to put them in the hands of more guitarists. But, in the end, even these proved too difficult to produce in the required numbers. “Too popular and time-consuming,” was his verdict. “I started turning down business offers… More work than time.”

Name Brand

During the 90s, Zemaitis was approached to license his designs to large offshore makers capable of producing enough good-quality guitars to make Zemaitis instruments widely available, but a deal was never struck.

Guitars bearing Tony’s name are still made in Japan and Korea, adding another twist to a story

But a year after Tony’s death in 2002, his wife and son made an agreement with the Japanese corporation Kanda Shokai to ensure continued production of Zemaitis Guitars. A high-end range of AC Zemaitis guitars were made in small numbers in a Japanese custom shop, while Greco versions, licensed from a newly established company, Zemaitis International, were more affordable and made in higher numbers.

James Hetfield and Japanese star Hotei are among the famous players of these legacy instruments, ensuring that Tony’s extraordinary guitar-making legacy continued. Today, as our review explains, guitars bearing Tony’s name are still made in Japan and Korea, adding another twist to a story that is as elaborate as Tony’s lovingly crafted guitars.

Not bad going, considering, as Tony himself put it: “The whole thing started as a pleasant hobby for an amateur player!”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.