Paul Weller talks new album Saturns Pattern

Musings from the Modfather

Introduction

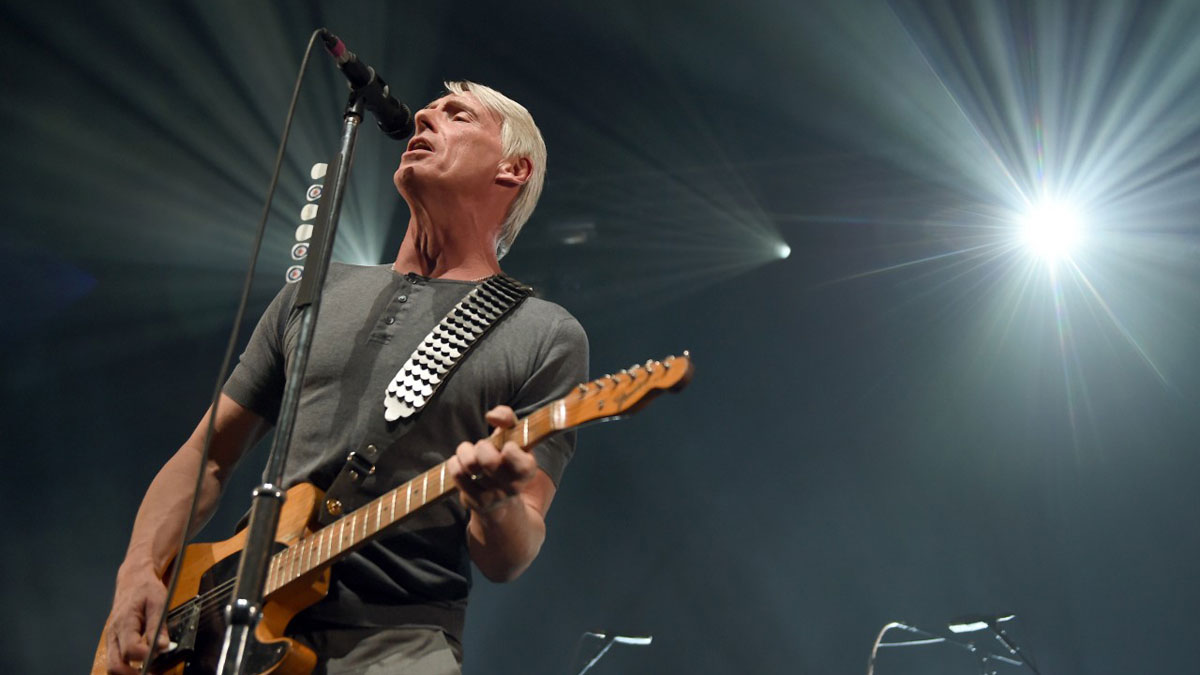

With Paul Weller’s latest album, Saturns Pattern, being touted one of his best yet, Guitarist headed to New York to seek an audience with the Modfather…

Paul Weller is relaxing in the bar of his New York City hotel, on a rare day off during the first week of a short tour of the States to support Saturns Pattern, perhaps the best in a string of excellent, genre-crossing albums that began with 2008’s 22 Dreams.

Weller knows how to craft short, sharp rockers, but Saturns Pattern jams it out just the right amount

“Most of the tunes started off with a drum beat and a riff,” he says of the creative process on the new record. “It could have been a bass riff, a guitar lick or something. Often we just started with a groove.”

Saturns Pattern has only nine songs, but it’s hardly short, balancing Weller’s beloved soul with swaggering T Rex-style rock. While stylistically adventurous, it also has a sharp focus, with a clear thread throughout.

Of course, Weller knows how to craft short, sharp rockers, but Saturns Pattern jams it out just the right amount, something that Weller tells us he was encouraged by new collaborator, producer Jan ‘Stan’ Kybert.

Something different

In fact, it seems Weller has taken everything great about his last three albums - 22 Dreams, Wake Up The Nation and Sonik Kicks - and crammed them into one, brilliant package.

My influences are all still there. But I don’t think this one is like anything else I’ve done

“I didn’t have a plan, as such,” Weller says. “But I knew I didn’t want to make Sonik Kicks Part Two. It’s not always possible to do something different every time, but that’s what I had in mind and I think we succeeded.

“Obviously, it’s still me. My influences are all still there. But I don’t think this one is like anything else I’ve done and I don’t think you can compare it to anything else that’s out there right now, which I really like.”

Saturns Pattern also sounds great. The mix is deep, rich and sparklingly clear. Weller attributes it to the fact that he has his own recording space, Black Barn Studios in Surrey, which allows him to create without ever having to watch the clock. Not known for his willingness to talk gear or about his creative process, Weller immediately digs deep.

“The only kind of grief I gave the team I worked with on this record was that I wanted it to have big drums,” Weller confesses. “I wanted the tracks to have some feeling of movement and dance, some sort of fluidity about it. That was kind of it, man - as vague as that.”

Alone among his peers from punk’s Class Of ’77, Weller continues to top the charts with vital music, filling everything from theatres in out-of-the-way towns to stadiums with shows that feature a setlist of more new than old songs. The Modfather is equally unapologetic about the experimental nature of Saturns Pattern.

“I never worry about what anyone will think,” Weller says, flatly. “I just follow my nose. I have a great team at my studio because I can’t be bothered with all of the technical aspects, so the sky’s the limit.”

That's entertainment

You might expect a man of Weller’s retro sensibilities to be strictly analogue, but in fact he’s a firm fan of digital technology and Pro Tools. “The depth is back, don’t you think?” Weller asks.

“I remember when I first used to work with digital recording that it was so flat. I think now it’s got some real depth to it. And what we’ve done on the past few records - and especially the new one - just would not have been possible in the old analogue days.

I think digital recording has got better, even in the last two years. The sound has much more depth to it

“There were quite a lot of songs, the majority of them really, where we had a groove and maybe would then add melody ideas on top of that. We’d leave eight bars, four bars, whatever it may be, and then come back to it later.

“Some just would have a count, or others we’d just have the drummer play a bit madly. We kind of did things like that, just piecing them together into songs. But the production team really made use of that whole editing facility.

“There are things you couldn’t do on tape, it would be impossible. It’s incredible. I think digital recording has got better as well, even in the last two years. The sound just has much more depth to it.”

As for the endless array of plug-ins available these days to anyone with a laptop, Weller welcomed them on board, too.

“We made really good use of those as well I think,” he says. “Things to warm everything up and make them sound more analogue - and great analogue gear, of course. That added an awful lot to the record as well.

“We also added a lot of weird shit that you wouldn’t expect - middle eights and stuff. Just twists and turns to make each song a little different, and the technology really aided that.”

Gallagher gags

When we mention that Noel Gallagher recently told us that he insists on working on one song at a time in the studio, focusing his attention in an effort to make each track the best it can be, Weller scoffs.

I’ve realised that there’s no wrong way to make records, and I think that was very freeing for me

“He’s from Manchester, that’s why,” Weller says with a chuckle. Then he becomes more serious. “We work on something, and if we feel we’re going somewhere with it, we’ll keep working on it,” Weller says.

“But we’ll equally do two or three songs a day as well. Not from start to finish, but I’ll get bored, so I like to jump around and stay energised.

“Sometimes, we’ll get through a couple of tracks in a day,” Weller explains. “Some take longer, of course. I had a few songs that I’d written, but they were acoustic songs, really, and that’s not where I wanted to go.

“We didn’t really have any songs to work with like I usually do, so we were making it up as we went along with no pattern to it, really. And if I felt like we’d hit on a pattern, I’d break it and start again.

“I’ve realised that there’s no wrong way to make records, and I think that was very freeing for me. I didn’t really know what I wanted, but I knew what I didn’t want. So I think that helped.

“We just experimented with sounds and songs until we hit a point on something that was exciting. Then we’d try to make it as good as we possibly could, but not too perfect, either. I like rough edges.”

Ever changing moods

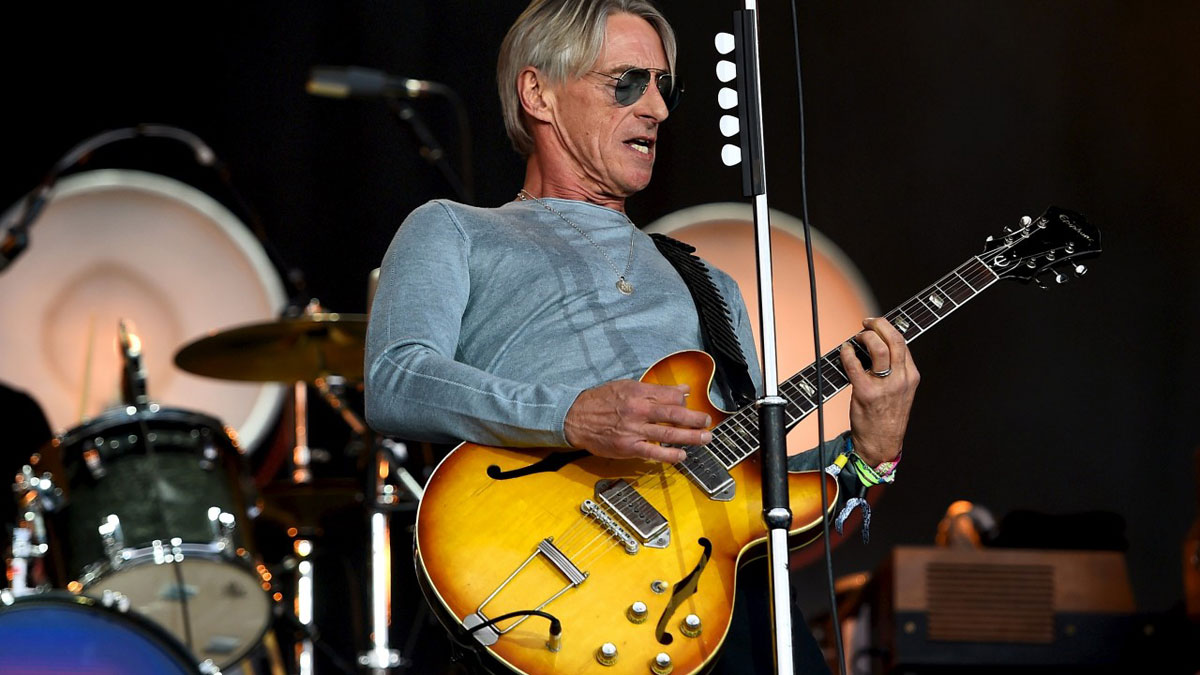

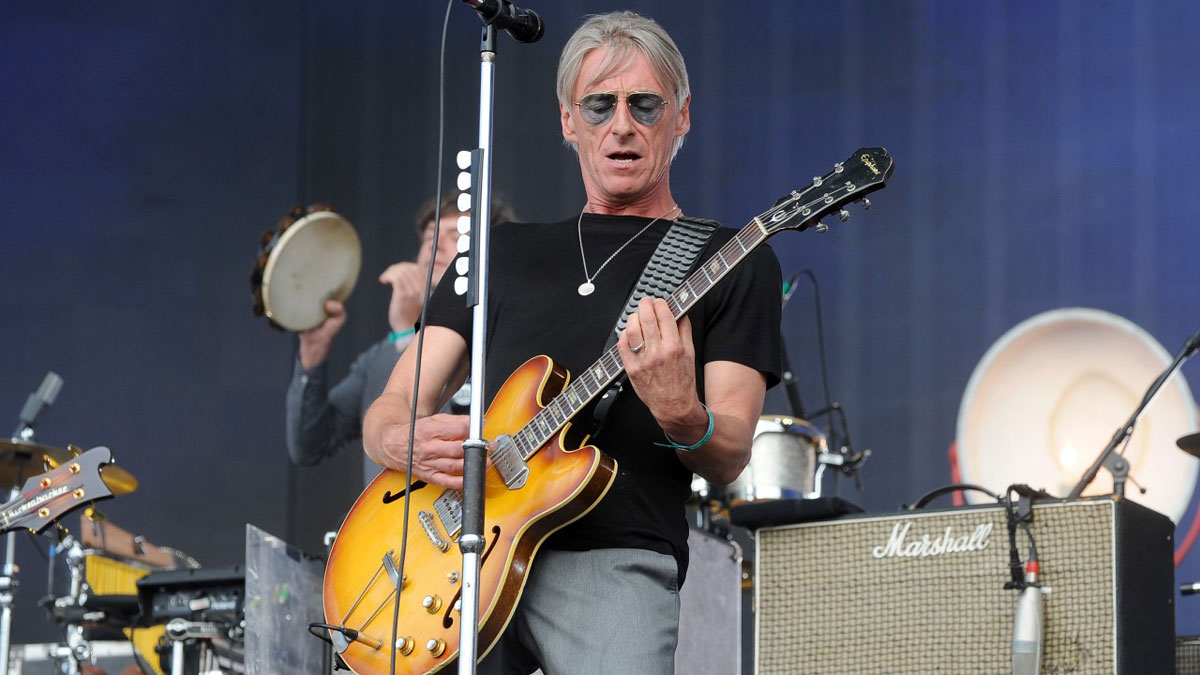

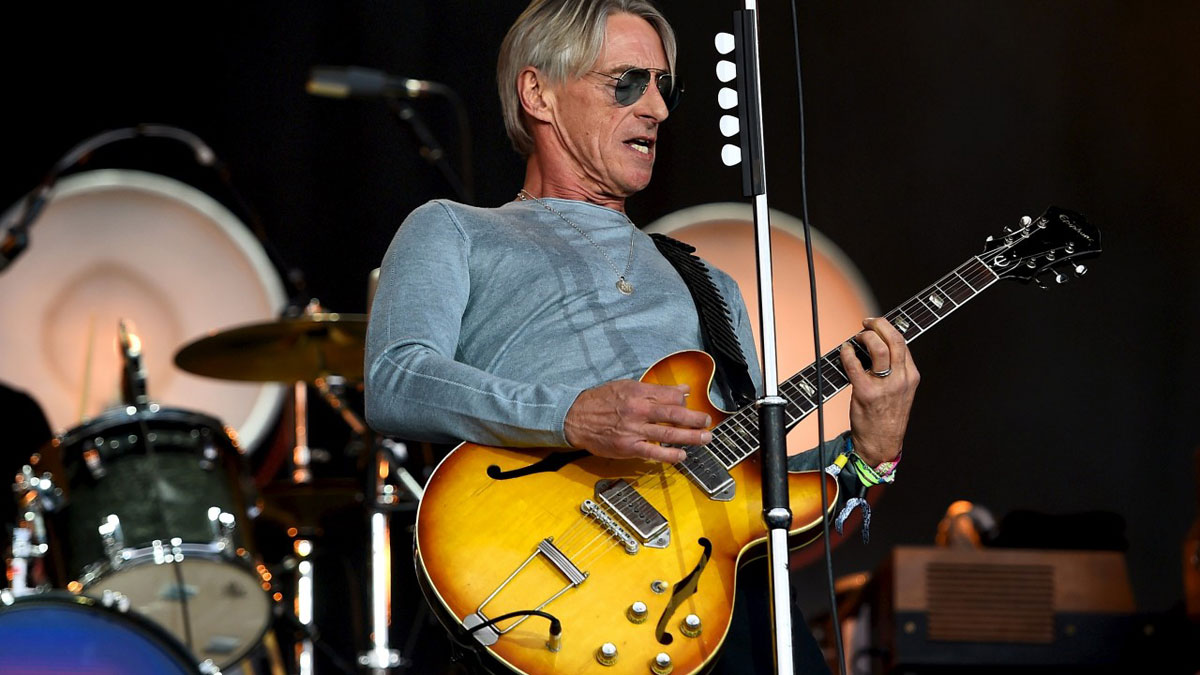

As for gear, Weller steered clear of the ’66 Epiphone Casino, ’66 Fender Telecaster and ’68 SG he’s known to use live, as well as the Rickenbackers he became so synonymous with in his early career.

“On this record, I used some Danelectros and a Vox Teardrop reissue,” he says. “I tended to just use those guitars as well as a President and a Club that Hofner sent me. It’s the same family, I think, after all these years, and they’re really great pieces. Really well made.”

I can easily get hung up with one sound. But I think it’s important to take yourself out of the comfort zone

As for effects, Weller is at a bit of a loss when we press him. “I don’t remember,” he says, and laughs when we ask him if he was indeed there at the sessions.

“I was there,” he says with a smile. “Kind of there. Let’s see: the main thing I used was this kind of synth pedal thing. It was blue and silver. Again, it was just to make the guitar sound different.

“I can easily get hung up just doing my thing with one sound. But I think it’s important to take yourself out of the comfort zone and do things you’re not familiar with, as well. It makes you play things differently and do things you wouldn’t do normally.”

We remind Weller that he mentioned the songs often started out as a drum and bass groove, with him on bass. Given that he was originally the bass player in The Jam’s early days, does he find himself missing playing a four-stringer?

“I had to stop because I couldn’t sing and play bass at the same time,” Weller says. “That’s fucking tough. But in the studio, I do like to play the bass. And I try to get Andy [Lewis, Weller’s touring bass player] to try and stick to what I’ve laid down, because that’s the groove. Once I’ve locked it down, we’re going with it.”

Back to the 'Barn

Sessions these days, though, sound loose. Recording in Black Barn, so close to his Surrey home, has not only afforded him the luxury of working without having to watch the clock, it’s allowed him to work in small bursts, whenever he pleases or is inspired.

Then he can go away and think about what he’s done, rather than working for several months at a time, often on deadline, the way he used to.

I’ve got family and friends who play as well, so whoever comes down gets to play

“It depends who’s there,” Weller says, when we ask him about how he divides up the guitar duties, often between him and longtime foil Steve Cradock.

“Usually, I’ll just say, ‘Are you around next Monday or Tuesday?’ and whoever’s around can come play on my records, and whoever isn’t, they won’t. So it’s one of those things, right? Whoever comes down to the studio. I’ve got family and friends who play as well, so whoever comes down gets to play.”

Sometimes, though, Weller can be more accommodating, as when Steve Winwood guested on the 1995 album, Stanley Road.

“That took some time to get him down, ’cos he’s a busy man,” Weller admits. “But it was great. Well worth it. It was Stanley Road, but we probably asked him around the time of [1994’s] Wild Wood!”

Paul Weller’s new album, Saturns Pattern, is available now on Parlophone Records.