Paul Reed Smith on 30 years of PRS guitars

PRS' big players talk

Introduction

Is it just us, or does PRS Guitars still seem like the new boy? Can it really be 30 years since the world - or at least a few interested people - saw the PRS Custom for the first time? It’s time to take stock of a modern classic, its legacy and what the future holds...

"It doesn’t feel like we’re a 30-year-old company... but in a good way"

"You’re right, it doesn’t feel like we’re a 30-year-old company... but in a good way,” laughs PRS president Jack Higginbotham. Jack is one of a handful of PRS employees who have been there since, virtually, day one - a brief departure aside, he’s been an ever-present face at the company.

“We don’t stand still for very long and things are always changing - a feeling of not being stagnant probably makes the time go by very quickly. We are always starting something new.”

Evolution

Inside the bubble of PRS, it’s an accurate statement that reflects the continuous improvement and evolution of the instruments it creates. Outside, however, many look at the outline of the Custom - the basis of the majority of PRS’s instruments over three decades - and think, ‘what’s changed?’.

Until the first EG, PRS had used the same body outline since it started. The second-series EG changed it and then the pre-factory body shape, known now as the Santana, reappeared in 1995. PRS’s most controversial body shape appeared halfway through its history, in 2000: the Singlecut.

With those early EGs long since consigned to history, today’s 30-year-old core line-up features just two primary outlines, with minor new shapes such as the Brent Mason - based on the NF-3 - and Neil Schon’s NS-14 enlarged, semi-hollow Singlecut.

Put simply, as many say Leo Fender ‘got it right’ with the first Stratocaster, Paul Reed Smith got it right with the Custom - a design that appeared in 1985, fully formed. But it was no accident. It was informed by the prior decade of making and repairing guitars, learning what was great about the classic models of the ‘golden era’ of the electric guitar and where they could be improved: a better tool.

Keys to the kingdom

History is littered with guitars that ‘seemed like a good idea at the time’, models that designers thought the musician wanted but, ultimately, they didn’t - certainly not enough to keep a brand in business over a 30-year period. There’s little doubt that we wouldn’t be writing these words if Paul Reed Smith hadn’t created the Custom.

It certainly wasn’t in fashion back in the big-hair days of the mid-80s. The ‘superstrat with a Floyd Rose’ ruled the roost, yet the Custom bucked trends with its evolutionary ‘hybrid’ design and mix of classic Gibson and Fender ingredients.

Not everyone got it, of course, and when we refer to the Santana-shaped, pre-Custom design - that got the twenty-something Reed Smith noticed by the likes of Carlos Santana and Al DiMeola - as a ‘double cutaway Gibson Les Paul with a vibrato’, Reed Smith today seems a little prickly.

“It was a heavily carved, curly maple topped, tremolo guitar and I’ve still never heard it called a double-cutaway Gibson!”

The McCarty mentality

There’s an awkward silence before a hint of a smile appears on the guitar maker’s face and a memory pops into his mind.

“I did actually tell Ted McCarty that the PRS McCarty was the double-cut they [Gibson] should have come out with back in the day. He didn’t like that very much! But he loved the guitar and the fact his name was on it.”

"He loved the guitar and the fact his name was on it"

Ah, yes, the McCarty Model, to give it its original name, is often seen as a more ‘vintage’ take on the original PRS design. But, in fact, the Custom was heavily informed by what we now class as ‘vintage’ instruments.

Stealing vs 'research'

The Custom’s outline isn’t a million miles from the Stratocaster, and the often-called ‘modernistic’ PRS design was drawn virtually exclusively from the experience Reed Smith had gained building and repairing guitars in the decade before he opened his factory doors.

“If you take all from one place it’s stealing. If you take from 10 places it is ‘research’. I saw this guitar more as research to me,” he says.

“It was like the tremolo,” he continues. “I didn’t completely draw that, it came from the heritage of Fender; the string spacing on it came from the heritage of Gibson.”

The Custom slowly evolved from those early instruments he made for Peter Frampton through to the now-famous early maple top guitars he made for Heart’s Howard Leese and Carlos Santana. By the end of 1984, the Custom was pretty much fully formed, drawing from the past but very much a new design.

Proprietary progress

“What was proprietary was the body shape, the scoop in the lower horn, the top carve, the type of belly carve, the shape of the back plates, how the electronics system worked with the five-way rotary [pickup selector switch], how it was wired, the knife-edges in the six screws in front of the tremolo, the way the [tremolo] arm didn’t break, the fact that you could put bullet-style strings in the bridge (which ended up long-term not working because I couldn’t get anyone to make them), the headstock shape, the headstock angle.

"I was making my living from ‘It’s a Hamilton’! I didn’t want that to happen with my guitars"

"The inlays were proprietary, the sweet switch was proprietary, the nut material, the tuners...” Smith pauses for breath, “Erm, how close the headstock was into the nut so the headstock wouldn’t break off if the guitar fell over...

“That was how I made my living at the time: there were these stands called Hamiltons, and it said on the stand ‘It’s a Hamilton’. Every time a [Gibson] fell off one of those stands I had a headstock to glue back on. I was making my living from ‘It’s a Hamilton’! I didn’t want that to happen with my guitars. It needed to be fixed.”

Jacked up

The smallest detail wasn’t overlooked either. “The fact that the jackplate on our guitars was made of brass so that if you walked out with the jack still plugged in you didn’t break the plastic plate that other people used.

"How many jack plates did I replace on guitars back then? It was all the things I’d found in the old repair shop that I thought needed to be fixed. Locking tuners and low-friction nuts so the tremolo stays in tune...”

Unlike the classics, the PRS Custom didn’t contribute to what many players think is ‘the rule book’: those iconic recordings and performances of early electric blues, through rock ’n’ roll to the golden age of classic rock. Hendrix didn’t play one. Yet, the upside is that those classic designs could be evaluated by Smith and others in retrospect: what did players really want?

“The neck shape, for example, was a combination of an old Tele and a Les Paul,” says Smith. “There was the 10-inch radius on the fingerboard, which I thought was proprietary at the time, but it turns out it wasn’t. I’ve measured a lot of old Les Pauls and it turns out they’re 10-inches: they were advertised wrong. Like the scale length. The Gibson scale length is 24 9/16ths of an inch, which is not what they advertise, but I measured it.

“If I hadn’t done all that repair work there’s no way I’d have put all these things on the one guitar - I wouldn’t have had the experience base. Fact.”

The 'posh' guitar

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and irrelevant of the improvements that led to the Custom’s design, its look can be polarising.

For everyone who loves its fabulously coloured and carved maple top, its natural edge ‘binding’ and bird inlays, there are the others who see it as a posh, ‘furniture’ guitar. But the company sells way more guitars with bird inlays than without, and the ‘prettier’ the top, the easier the sale.

“Yeah, but I’ve finally figured out why people like ’em!” exclaims Smith of his famous bird inlays. “I never figured it out before. What the hell’s that all about? We put the birds on because my mother was a birdwatcher and it made sense, but I didn’t think anyone would order them.

"The birds made sense on a visceral level at the time"

"I later realised, well, there are birds in every yard in the world, there’s not a dog in every house but there are birds in every yard, right? Even in the desert you’ll find a bird every once in a while.

"The birds made sense on a visceral level at the time but I honestly didn’t think they would catch on. I thought it would be the moon inlays - fancy dots, if you like. Now, it’s the birds that seem to make sense to the world.”

Good, but it could be better

So, if Smith created the Custom way back in 1984, what has driven him to constantly alter and improve so much of the original’s design?

Well, compare the original ’84 prototype with a 30th anniversary Custom, and virtually every detail - the shape of the body and headstock aside - has been re-evaluated over the past three decades.

“Well, the control knobs kept breaking, let’s start with that,” says Smith. “They were made out of Plastiglas and they would crack, and so we had to start playing around with our own design, and when you do that, well, I wanted them to be serrated around the edges and a little smaller in diameter so you can get your little finger around them.

"We’ve actually redone the moulding three times over the years before we got to what we have today. Now we think they’re perfect; all the edges are rounded, right? We’re not going to touch ’em.

"See, they’re not really very different to those,” he says, pointing to the standard speed knobs on the ’84 Custom prototype, “but with these new ones I never, ever struggle to get the volume to the right place. and if the knobs were breaking why would you keep using them? Is that fair to your customer?”

Fine-tuning

Once PRS started producing guitars it was its own instruments that were under the spotlight and being assessed.

“Take the original five-way rotary pickup selector switch,” says Smith. “People complained about it. They said it was difficult to control; so we put on a three-way [pickup] switch, but they said ‘but that doesn’t give us all the sounds we want’.

"We finally figured it out and got a five-way lever switch company to make it right, so we have the rotary-switch type sounds but on a more conventional five-way switch. It’s [virtually] the same wiring as the five-way rotary, but on this lever or slide switch. So it’s not that we changed it for the sake of it, it was because people asked us to change.”

The original cam-locking tuners are another example. “Those original tuners were hard to make, and people would send their guitars in for repair and half the time they didn’t have ’em strung up right. Now when people send their guitars in with these new tuners on, a way smaller number aren’t strung up right and it’s usually that people put just too many winds around the string post - defeating the entire purpose of locking it down on the shaft.”

“Getting the gearing right, seemingly little things, it all takes time and money, but we finally got that right, too"

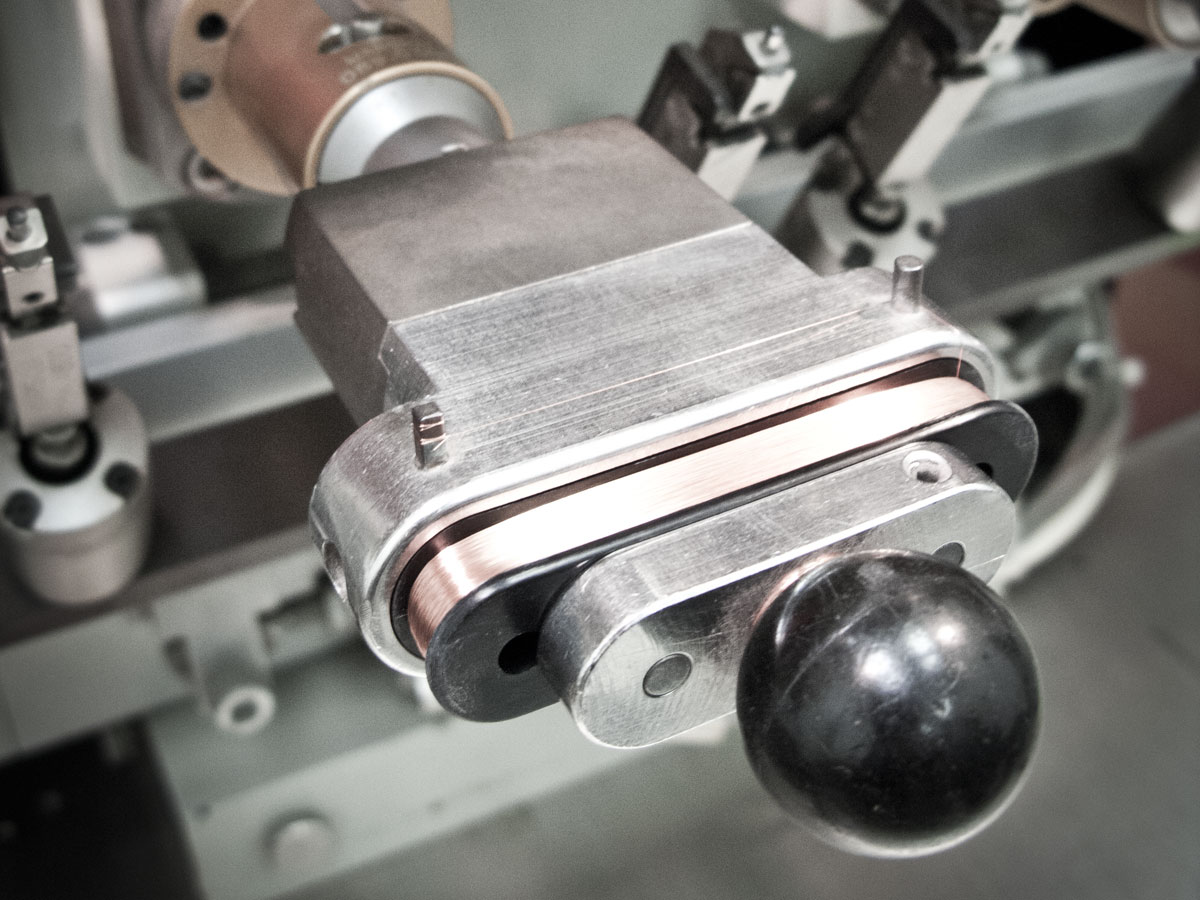

The lighter-weight, open-backed Phase III tuners that grace the modern Custom do appear a much more thoroughbred version of the original Schaller M6s with their cam-locks.

“Getting the gearing right, seemingly little things, it all takes time and money, but we finally got that right, too. The worm and the gear sit together beautifully.”

Yet it’s this attention to detail, combined with the quality of the craft, that from day one gave PRS a reputation: a high-end guitar that ‘normal’ people couldn’t afford. Throw in those ultra-curly maple tops, a wide colour choice, and the far from classic bird inlays and the posh-looking ‘furniture’ guitar was with us.

Quest for affordability

PRS has never forgotten the everyman. Two years into its history, the company released the Classic Electric, a more affordable bolt-on, followed by the lower-cost EG series.

Neither are made today and remained in the shadow of the higher-ticket guitars, such as the Custom, Standard and McCarty. a decade and a half ago, the SE series launched, made in Korea: lower-cost replicants of the USA guitars aimed at a different player.

There was still a big gap in the middle of the range, however, and that took 28 years to sort, until PRS launched its S2, in 2013, a range that’s virtually half the price of the core models but still made in the Maryland factory.

"S2 is about a new artist, new customer and price point"

“The S2 is more thinking about satisfying someone else’s desire - I want to talk to that guy,” muses Higginbotham. “Being able to have a conversation with someone that I couldn’t because we didn’t have the right style or price point. S2 is about a new artist, new customer and price point - almost a new business after nearly 30 years of making and selling guitars.

“It’s almost a second-generation PRS for those coming into this business; it’s a different tone and look - it’s what we want to play,” says Judy Schafer - one of PRS’s younger staff.

“The one doesn’t have to play the other: the S2, I believe, will become its own thing."

“What does the future hold?” asks Jack, repeating our question. “30 years is just a moment in time. We’ll celebrate, of course, but it wouldn’t be PRS if it wasn’t the dynamic, moving company it is.

"For our customers’ sake, we’re doing a better job but I think, in the future, we’ll be a bit more consistent in terms of what we offer. If we think something is an improvement then we’ll do it. We can’t help it: it’s not a choice.”

But how much can you improve the instrument? “How far would you have thought it would go 25 years ago? I remember that 1,000th guitar party,” says Jack of the 1986 celebration.

“I remember saying to Paul: ‘there can’t be too many more people that want this... so what are we going to do?’”

New directions

PRS makes acoustics and amplifiers, too. The decision to push the new S2 line centre stage means the intended expansion of acoustics has been put on hold; PRS seems content enough to make a small number of acoustics at high-dollar prices within its Private Stock programme.

“That’s the market where they see the advantage,” reckons Smith. “at one point, we lowered the price 35 per cent, it caught on for one minute then people went back to wanting the high-end piece.”

“People said the 100-watt amp head market was dead”

Its amp production has hit pay dirt with the Archon. “People said the 100-watt amp head market was dead,” says Reed Smith. “I said, ‘no it’s not: the problem is people don’t want to buy the 100-watt heads out there.’”

But regardless of any new directions it might take, to misquote the song, PRS really has built this city on the Custom. What of the next 30 years?

Dave Burrluck is one of the world’s most experienced guitar journalists, who started writing back in the '80s for International Musician and Recording World, co-founded The Guitar Magazine and has been the Gear Reviews Editor of Guitarist magazine for the past two decades. Along the way, Dave has been the sole author of The PRS Guitar Book and The Player's Guide to Guitar Maintenance as well as contributing to numerous other books on the electric guitar. Dave is an active gigging and recording musician and still finds time to make, repair and mod guitars, not least for Guitarist’s The Mod Squad.