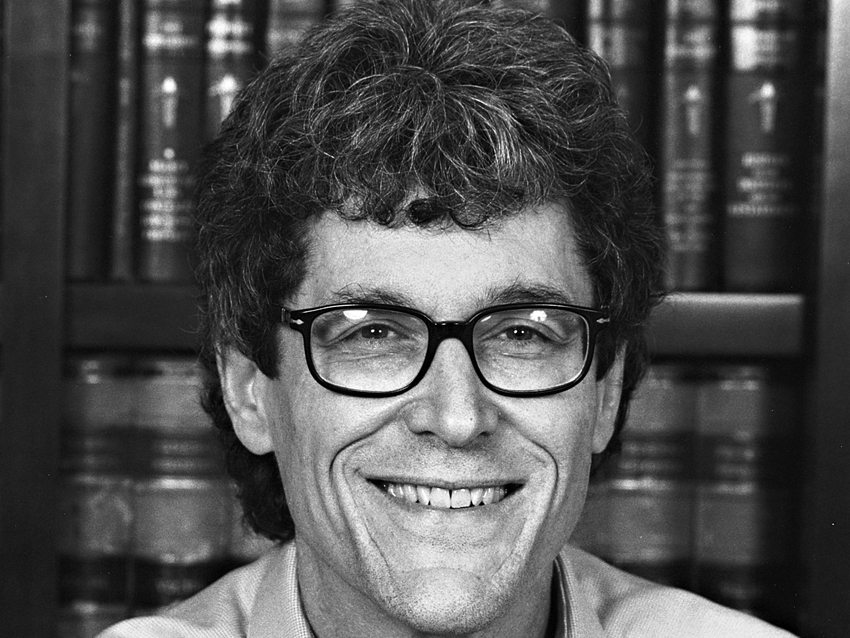

Donald S. Passman has been a music business attorney for over thirty years. Currently he practices law with the firm Gang, Tyre, Ramer & Brown, Inc. - their clients include Green Day, Pink, REM, Radiohead, Tom Waits, among many others - and he's just published the seventh edition of his top-selling book, All You Need To Know About The Music Business.

"I can honestly say that the music business is still fun," Passman says. "But I have to qualify that by saying it's a different kind of fun.

"It's not fun in the 'ha-ha' way it used to be when you signed a band to a deal and watched them sell 10 million records. Those days are pretty much over. The fun is trying to figure where we're headed, figuring out the different ways to break artists and trying to make sense of the delivery systems which are changing all the time."

While readers intent on a career in the music business would be well served by picking up the updated copy of Passman's book, MusicRadar managed to extract a few morsels of advice from rock's top legal eagle in the following interview:

What are the main differences between this seventh edition from previous ones?

"The biggest changes are what's going on with 360 deals and the enormous update needed to explain what's happening with music in the digital realm. Three years ago, there was very little precedent and we were all groping around in the dark. Now we're still groping around in the dark but at least we can feel the contours of the furniture.

"Both of these aspects have become the biggest and hardest to understand components of the music business today, and they're areas musicians should absolutely familiarize themselves with, whether they have an attorney or not."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Unless you have some sort of enormous bargaining power, it's almost impossible to get a deal these days that isn't a 360" Donald Passman on labels participating in all aspects of artists' revenues

As far as 360 deals go, has the business figured out a general paradigm?

"These kinds of deals are still works-in-progress, and surprisingly variant from label to label and artist to artist. The percentages vary, and the way they compute their percentages vary. Some labels take what's known as 'active rights,' meaning that they want to own the publishing and merchandising versus 'passive rights' where they just get a percentage of the income."

For artists, what's the upshot of a 360 deal?

"The upshot is that you get a record deal. [laughs] Unless you have some sort of enormous bargaining power, it's almost impossible to get a deal these days that isn't a 360. It's become the reality of the world, not just with majors but with independents as well.

"Obviously, if you're an established artist, you can reduce or eliminate the percentages the label takes to where things work in your favor. If you're a new or mid-level act, you're going to have to settle for a deal where things are stacked more in favor of the label."

Still, 360 deals are now the norm? Even if you're an act out of Bumfuck, Iowa?

"Absolutely. Labels are taking an enormous risk by signing you, and they want to do everything they can to reduce that risk. Owning as much of you as they can is a way to get some sort of return on their investment, particularly nowadays when the business is distressed."

'Distressed' - that's another way of saying 'shrinking'?

"Well, it's shrinking as far as the old way of doing things. But there's other avenues now, such as digital streaming and downloads."

Has the industry come close to a final model for streaming and downloads?

"They're getting close, but then that final model won't be final. The music business is always evolving. But yes, the general parameters are there. If it's streaming, there's going to percentages going to the labels and publishers of the ad revenues or subscription monies, sometimes with minimums, whether it's per-stream or sometimes if's there's a minimum based on the company."

Even so, the Internet can feel like the Wild West at times. Bands - new and established - are offering tracks for free, for twenty-five cents; groups are streaming albums for free before they're released.

"It can feel like the Wild West. We're in the midst of a major transition of the business, which is going to have to reinvent itself if it's going to survive."

Are you hopeful that the business can do just that?

"Yes, I am. Very. There's the ability in the future to get music to people who might never go into a record store and to monetize it. People mostly stop buying music in their early 20s, and yet, here we have the ability to get music to consumers who might not normally hear it or see that it's available. Even if the amount per transaction is much smaller, if we multiply it by the people taking part, the business can grow and become bigger than it ever was. I'm very hopeful."

How has your role as a music attorney changed over the past ten years?

"Things have changed radically. Everything has gotten much more difficult. Companies have become distressed, and distressed people don't always make the most reasoned, dispassionate decisions. If you're the pilot of a plane and you're cruising along at 40,000 feet and the weather is calm, you're going to act a lot differently than if the plane is nose-diving and plummeting towards the ocean.

"Budgets are tighter; bands aren't given the same amount of time to grow as they used to; and on top of it all, the deals are smaller. It's just tougher all the way around."

"People at record companies are worried about losing their jobs, and the CEOs of those companies are worried about going out of business entirely. Budgets are tighter; bands aren't given the same amount of time to grow as they used to; and on top of it all, the deals are smaller. It's just tougher all the way around.

"My role hasn't changed as much as you might think - the artists are still doing what they were doing before. The only thing that's changed is that I've had to learn exactly what's happening in these new technologies in order to advise artists properly about it all. The landscape has changed; I haven't." [laughs]

Back in the '80s and most of the '90s, there was a set pattern to getting a record deal: A band formed in a basement, they played gigs, toured in a van, they put out an indie single or two, and before you knew it there was a swarm of A&R people flying to Lexington, Kentucky or wherever to try sign them to a million-dollar deal.

"It doesn't work that way anymore. The good news is, it's now very easy to get your music out to the public. The bad news is, it's very easy to get your music out to the public. [laughs] That's why there's five million bands on MySpace.

"Therefore, how do you break through all the noise and build a base and a buzz? Interestingly, a lot of these bands are doing it better than the record companies. They collect e-mails and keep in touch with fans, let them know about what they're doing, when they're appearing in their town, and in some cases they're able to move their careers forward all by themselves."

When you come in contact with a band that's built up a buzz on MySpace, what kind of advice do you give them? How do you help them move to that next level?

"It all depends on what they want and what kind of band they are. If they're a mainstream band and want to break through internationally, they're still going to need a record company behind them. I'm sure a band will come along that does it without a major label, but it hasn't happened yet."

"If it's a band that's in a niche and they're comfortable with that niche and they know their commercial potential is limited and they only want to appeal to their hardcore fans, then they probably don't need a major-label deal. They might even make more money without one because they'll keep a bigger piece of the pie and they won't have to give up any 360 rights.

"But I will tell them, they have to fight harder for every dollar and every fan. They have to do their homework and keep moving. They can't be complacent because there's so many other bands fighting to be heard. They're in business for themselves, and they have to treat their bands like a business.

"Understand, though, that I don't see a lot of new, young bands anymore. But if they're looking to get their music shopped, I try to help them. I'll also try to help them get a good manager. And I'll help them try to find a distributor, whether it's a major or an indie. Or if they don't want to go the physical route, I'll help hook them up with a digital distributor like TuneCore."

What's your opinion of artists like Radiohead - a client of your firm - and Trent Reznor who have said 'See ya later' to the majors and sell their music on their own?

"The good news is, it's now very easy to get your music out to the public. The bad news is, it's very easy to get your music out to the public."

"If they get to that position to do it on their own, hey, more power to 'em. They're able to make more money that way, even if their sales are 40 to 50 percent of what they would have done with a record label.

"It's harder for mid-level bands to do this because they still need the kind of exposure and promotion that labels can give them."

Where do you see delivery systems headed?

"One of the main models is what I call a cross-platform subscription: you pay a monthly fee and you get your music anywhere you want it, whether it's on a computer or a connected device like an iPod, but also in your car stereo or even in a plane. When we can deliver that, it's a real business. Unfortunately, we're not there technologically, and we're certainly not there legally - it'll be a very complex business model to put together."

What about the way music is actually formatted? Do you think the album is dead?

"The album is dead. I think we're in the 1950s and we're in a business of singles."

"Ultimately, yes, I think the album is dead. I think we're in the 1950s and we're in a business of singles. Other than a handful of artists who make coherent albums with beginnings, middles and ends, I think records are collections of singles with added cuts - that's what albums used to be and we're right back to where we started.

"I don't see how albums can survive if that's the format. Back in the '60s, labels would put singles on an album as a way to get you to buy the album. Now, however, you can just buy a single on iTunes or wherever. I'm even hearing that retailers are pushing for EPs - releases with only five or six songs on them - because they know that the public has lost interest in full albums."

So this all goes back to the 360 deal, where a label has a piece of the whole pie: publishing, touring, merch.

"Yep. That's where things are headed. We're pretty much there now. Artists have to get used to that fact and understand how to make the system work for them. It can be done. You can still have a fabulous career as a musician. I wouldn't be doing this stuff if I thought all hope was lost."

Buy All You Need To Know About The Music Business here: Amazon

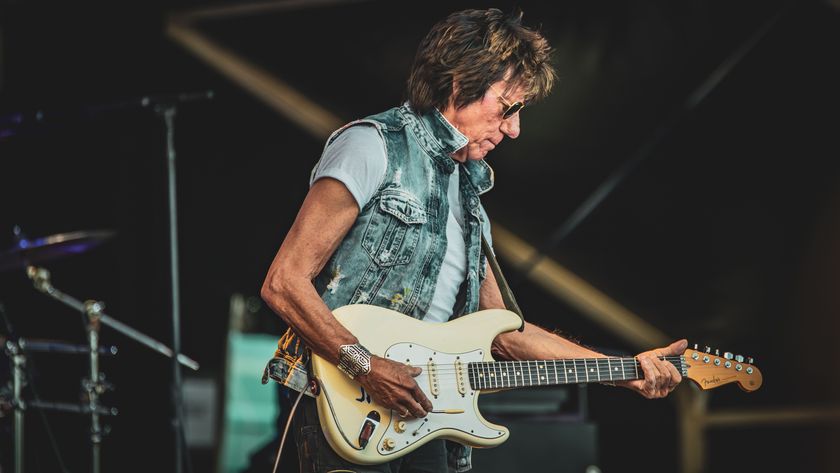

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.