Music legend Kenny Rogers looks back on his illustrious career

"It's one career... but several episodes"

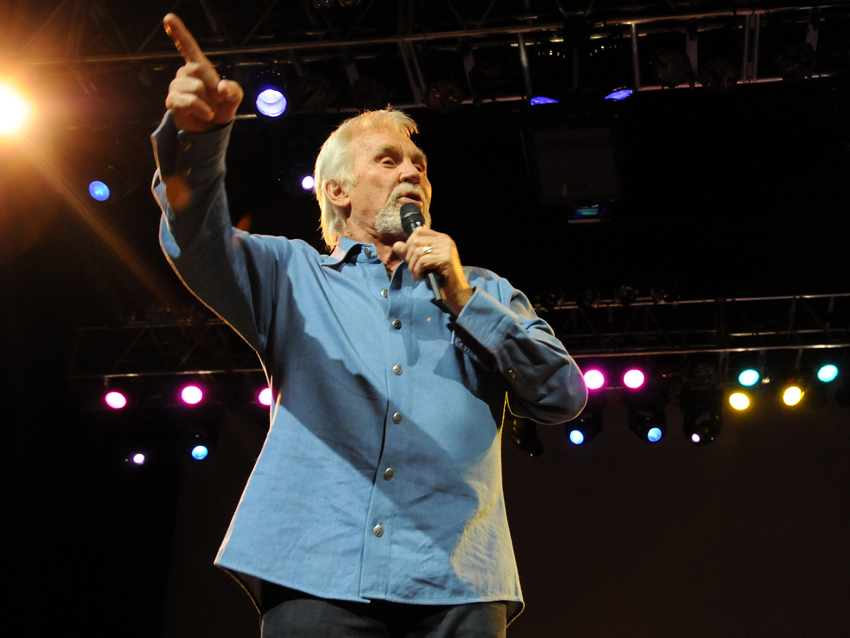

Kenny Rogers looks back on his illustrious career in music

These days, Kenny Rogers is in the advertising business. GEICO, the car insurance company, signed him up for a television spot in which he annoys fellow poker players by singing his signature gambling song under his breath.

The past few years have also seen him release a worthy, new collection of sentimental tunes, You Can’t Make Old Friends, and win over the millennial crowds at Bonnaroo and Glastonbury, along with the sort of mile-marker moments you’d be more prone to expect from a septuagenarian superstar. After publishing a memoir and being inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, Rogers has just become the subject of an exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, Kenny Rogers: Through the Years.

The day that MusicRadar sat down with the Houston-bred singer at the museum, an array of artifacts awaited display in the gallery space. There was rather dignified western attire he wore in the TV movie role of The Gambler, the sheet music to some of his singles, a framed award as long as a dinner table recognizing 12 times platinum sales of his Greatest Hits album, a wooden tambourine like those he tosses out during shows, more than one concert poster and such period-embodying stage clothes as a bejeweled, denim outfit from Tony Alamo of Nashville that he wore with the psychedelic folk-rock group The First Edition. The tangible items proved a good jumping off point for discussing Rogers’ career, long and varied as it’s been.

(For more information on the Kenny Rogers: Through The Years exhibit, visit the website of the Country Music Hall Of Fame And Museum.)

So many of the interviews you’ve done have begun with interviewers quoting back to you how many albums you’ve sold, lumping everything together as though there was no difference between your era fronting The First Edition and your decades as a solo artist. But it’s really one of the greatest second-act stories in popular music.

“Yep. It’s one career... but several episodes.”

Weren’t you approaching 40 when you launched your solo career?

“I think I was 35. Because I remember [producer] Larry Butler went to war the president of the record company. [The president] kept saying, ‘He’s too old.’”

How likely or unlikely did it seem to you at the time that your solo country bid would work?

“You know, I’ve never thought in terms of that. Because when I went with The First Edition, I was the oldest one in that group. So they didn’t want me, because I was too old. So I went and I grew my hair, grew a beard, put an earring in my ear, put on some sunglasses.”

On song appeal

Above: Rogers (top) with The First Edition and BB King, 1972.

And you got the denim Tony Alamo outfit that’s in the exhibit.

“Yeah. [And the band members said], ‘Okay, that’ll work.’ And then from there, when I came to Nashville, Larry Butler believed in me. He said, ‘This guy can sell songs.’ Because I’m a storyteller, first and foremost.

“So I looked for two different types of music. One is ballads that say what every man would like to say and every women would like to hear. If you listen through the years, [there’s] She Believes In Me, You Decorated My Life, Buy Me A Rose, Lady. And then the other section are story-songs that have social significance: Reuben James, about a black man who raised a white child. Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town – a Vietnam War vet comes back, and his wife’s having an affair. Coward Of The County was about a rape. And how many people sing about rape? It’s a great story. And I think that’s where my strength has been.”

Did you ever feel like those two kinds of songs were in conflict with each other?

“No. I’ve always felt that the love songs were for the women and the story-songs were for the men. I mean, I watch people, what they sing along with. Coward Of The County? Every man there sings it.”

On the subject of songwriting, didn’t you actually go to high school in Houston with Mickey Newbury, writer of Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)?

“I did. He wanted to be in our group, The Scholars. I said, ‘Mickey, you don’t sing and you don’t play anything. What are you gonna do?’ He said, ‘I’ll learn.’ He literally took one summer [to learn], and played guitar and sang as well as he sang when he died. And then he was too good for us.”

How much did you two have in common back then in terms of your musical taste?

“Nothing. I was listening to doo-wop music and R&B, just ‘cause that’s what was big, particularly in Houston. That was a very black [music] culture through there. And I loved that. Ray Charles was my hero. And Sam Cooke. Sam Cooke had the kind of smooth voice that was really a wonderful sound. And that’s what I wanted to do.”

Tossing out tambourines

When I saw the artifacts that are going in the exhibit, it struck me that there’s only one instrument in there – a tambourine. Where’s the bass you played in the jazz group?

“That I gave to my oldest son, and he’s having trouble getting it out here. I’m not sure he has a hard shell case for it. He’s trying to get it here – and my electric bass that I played in The First Edition. I do have a guitar. I should bring that up here. I’ve got a classical guitar that I wrote a lot of songs on.”

In the jazz group, The New Christy Minstrels and The First Edition, you always had an instrument in your hands. Since going solo, you’ve mostly had a microphone in hand. How did playing an instrument or not factor into the kind of performer you wanted to be?

“I think when you start walking around that doughnut [a circular stage piece surrounded by the crowd on all sides], you can’t do it with an instrument. I saw artists that played guitar that would open for me, and they’d have to sit down. Move your stool and sit down. Move your stool again and sit down. I just didn’t want to get into that.

“Plus, other guys played better than I did. So why not have better players playing? Above everything else, I always wanted to be an entertainer. I want people to leave saying, ‘I enjoyed that.’ Right now, it’s hampering me a lot, because I can’t move as well. So I sit down more on stage than I used to. But I’m on a flat stage, and I have ways of explaining it that are self-deprecating. I love that kind of humor.”

That works really well.

“It does. I mean, I think that people know you don’t take yourself seriously, so it allows them to have fun with you.”

Back to that tambourine – you’ve been tossing tambourines to the audience for years. That seems kind of risky, since so few people actually know how to play one.

“Well, I give it to them the last song. I used to throw Frisbees as well as tambourines. And I got really good. I could pick out somebody out there, and I would throw it out and it would wend its way back, and I could hit people a hundred yards away. Then a lady got hurt, ‘cause a bunch of people went for the same Frisbee. I had a huge lawsuit, so I quit doing Frisbees.”

How did the tambourine thing start?

“I’ll tell you exactly how it began. When The First Edition broke up, I had a little group I put together, and we went overseas to work. We sang for all Pakistanis, who spoke no English. They would sit there and look at me. I had five tambourines in my case, and I would throw out those tambourines. They had fun with those things. Then I had to get [the tambourines] back each night, and that wasn’t fun. That’s how it started."

Hits are costly

“As an entertainer, my job is to break that barrier between artist and audience. And you do that with humor; you do it physically. I do a thing where I throw a guy 10 bucks for every hit he can name. God knows how much money I’ve thrown away. It’s a continuing joke throughout the show, and I love those.”

Since you’ve done so many different kinds of music and been promoted in different formats, people who focus on categories – journalists, for example – haven’t necessarily known how your various phases of output square with your musical roots. How have you thought about all that?

“I’ve always felt that I was a country singer with a lot of other musical influences. I got into jazz accidentally, because I met this guy who was blind, and he taught me how to play bass. And for 10 years I worked with him. We made a lot of money, and we were very good at what we did. So I could take pride.

“And when the group broke up, I went to The New Christy Minstrels. Because a friend of mine, who was a friend of the guys who had bought the Christys from [founder] Randy Sparks, said they were looking for someone to sing high who could play bass. So I get on the telephone at the Houstonaire Hotel in Houston and I’m singing [sings softly], ‘Green, green, it’s green they say.’ And the guy said, ‘No, you have sing louder.’ So I’m [sings louder], ‘Green, green…’ And people are walking by. That’s how I auditioned. They accepted me, so I did that.

“Then The First Edition, they weren’t gonna let us sing on the records, because they didn’t wanna have to pay royalties. They hired studio guys who they paid a certain [fee] to. So we said, ‘Wait a minute. This isn’t gonna go anywhere for us.’ So we started our own group. Then when that group broke up, Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town, Reuben James, a bunch of songs we had had made the country charts. So I came to Nashville and I met Larry Butler, and he believed in me.”

The exhibit features outfits you and Dolly Parton wore when you sang together, and those that you and Dottie West wore, too, which reminded me of the many, many duets you’ve done over the years.

“Most of the people were [just for] one record. Sheena Easton: We’ve Got Tonight. Kim Carnes: Don’t Fall In Love With A Dreamer. Ronnie Milsap, Tim McGraw…"

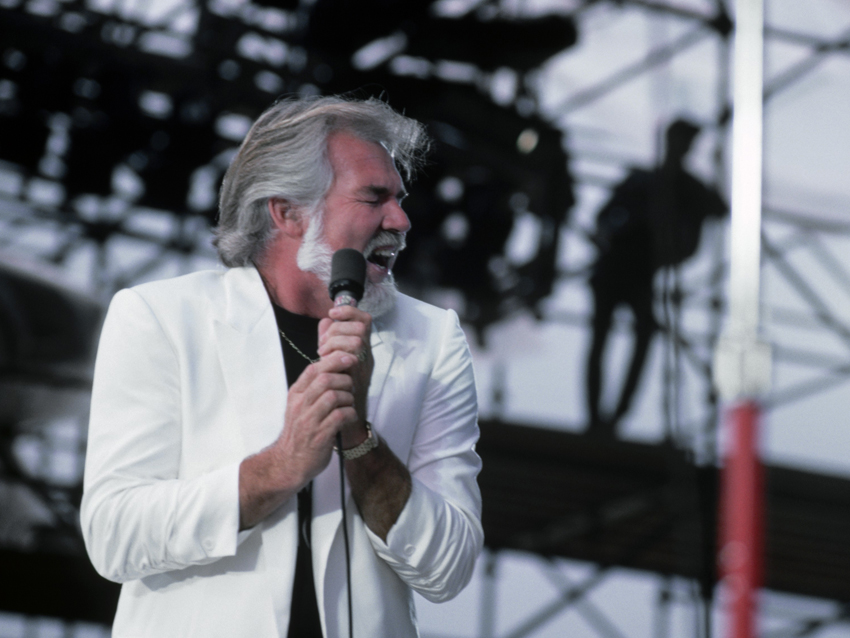

On duets

Above: Rogers on stage with Lionel Richie and Dolly Parton, 2010.

“I like singing duets. I think I sing better in duets, and I think whomever I’m singing with sings better. Because it’s a little like running the hundred yard dash: You get out and you run it as fast as you think you can. But you put someone next to you that runs it faster, and you’re going to run it faster. And it’s the same thing with duets. You sing a song as best you think you can, then you hear somebody and you say, ‘Oh, wait a minute. Let me redo my part now.’ It brings everybody up [to a higher level of performance].

“The thing about records is, you always sound like yourself. When you can add coloration to it, people don’t get bored with you, because they have the opportunity to enjoy somebody else too.”

The duet you released with Dolly Parton last year, You Can’t Make Old Friends, is a Don Schlitz song, isn’t it?

“Yes. He wrote [my song] The Greatest also, about the little kid that plays baseball. He wrote another one on this album [last year] called Don’t Leave Me In The Night Time. It’s kind of, what do you call it? Zydeco.

“I called Don Schlitz and I said, ‘I have a title I’m gonna throw at you. Tell me what you think: You Can’t Make Old Friends. He said, ‘Can I have a shot at writing that?’ I said, ‘Sure.’ The next day he sent me the song.”

You joked at one point that you planned to record a Don Schlitz song every decade or so.

“There’s another guy named Mike Reid, I just love his songs. One of the songs on this new album is Look At You. It’s a beautiful piece of music. He’s a football player, for God’s sake – professional football player. He also wrote I Can’t Make You Love Me. He writes these wonderfully tender songs. And I have to have one of his songs on every album I do.”

You’ve found song sources to rely on.

“I can write, but good songwriters have a need to write – and I don’t have a need to write. You put me in a room with songwriters, and I’ll contribute. I’ll make a difference in that song. But I don’t play guitar anymore because my hand’s messed up. You can’t do it without some musical instrument. And I don’t feel a need to write. There’s so many people who do it better and quicker than I do. I’ll just use them.”

His biggest influence

We haven’t talked about the most famous Don Schlitz song in your repertoire: The Gambler. There’s a difference between a song becoming a signature number and becoming as intertwined with your identity as The Gambler is with yours.

“Yeah. Like the GEICO commercial.”

What were your initial thoughts on stepping into the role of the Gambler in a theatrical context?

“It came about accidentally, honestly. If you look at the album cover, it looks like a picture shot on a film set. I was performing for CBS in LA. Ken Kragen, who was my manager then, goes over to the guy who’s head of CBS at the time and he says, ‘Doesn’t that just look like a movie to you?’ He says, ‘Oh, it does! We should do that.’ So we did five of ‘em. All five of ‘em independently won the sweeps for the network they were on. And that’s a big deal.”

As for more recent evidence of your pop culture impact, what did you make of it when you heard Ludicris name drop you during Jason Aldean’s Dirt Road Anthem?

“I always think that’s really cool. There’s a couple of guys, rap guys, that have done The Gambler in various ways and have let me be on it with ‘em. That’s what’s always amazed me, is my acceptability – is that the right word? – to these other genres. I’m really well received in the black market. [Maybe it’s] because Ray Charles was my real influence. When I was 12, I went to hear him sing, and I just fell in love with him, and that’s what I wanted to be – Ray Charles. But I don’t have that gift.

“It surprises me that there would be that acceptance there. Now, in all fairness, I don’t know [if that’s the case with] the new, young guys. But I know that during the peak of my career, that was a big part of my audience. I was walking down the street in New York City one time and Sean Combs jumps out of a Rolls Royce. ‘Hey, Kenny Rogers! How ya doin?’ I was just shocked that he even knew who I was.”