Michael Rother's 10 tips for guitarists

Thoughts from the Kraftwerk and Neu! guitarist

Introduction

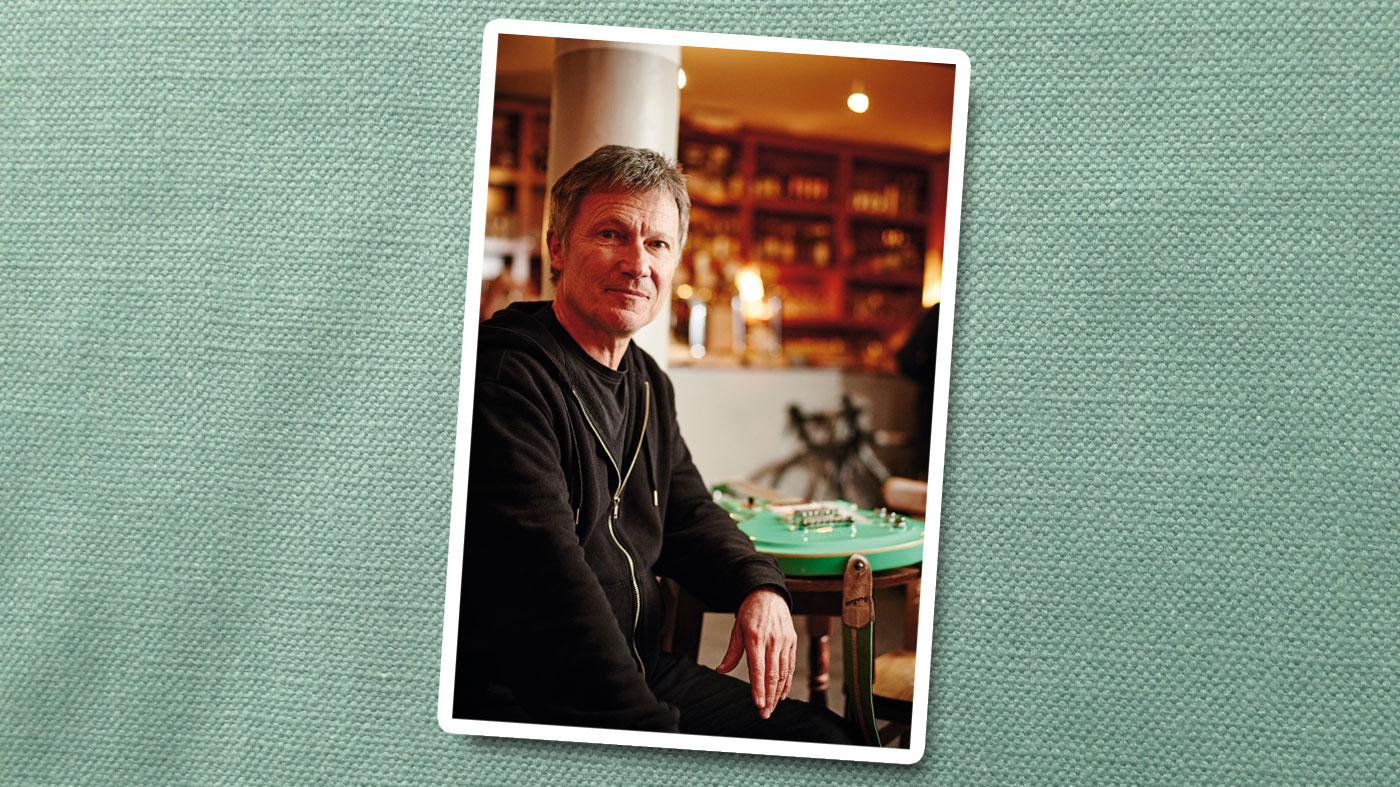

Former Kraftwerk, Neu! and Harmonia pioneer Michael Rother lifts the lid on Pakistani influences, onstage surprises and why he’s never liked the term ‘Krautrock’.

Since the early 1970s, Michael's highly innovative and experimental approach to guitar, keyboards and production has influenced generations of boundary-pushing pioneers. As an early member of Kraftwerk, a co-founder of Neu! and Harmonia, and a respected solo artist, Michael has always skirted anything commercial, commonplace or retrospective.

For him, music has been and always will be about diving into uncharted waters. We caught up with him in London…

1. Find The Magic In Old Gear

I work straight into the mixing desk. I record straight into the audio interface, and even during the analogue times, I would use a DI straight into an equalizer

“I’m not a gear-focused musician. To be honest, the idea is always the most important aspect of musical creation and performance, but then, of course, I do have some nice guitars and I can’t part with any gear I’ve used for my music.

“My first electric guitar was an Ibanez, an imitation. I got it in 1965, I think, before I joined Spirits Of Sound, my school band. Later, you can hear some modification I did with that guitar on some Neu! tracks. I tuned all the strings in different octaves of D and you can hear it when I used a small bottle or piece of metal for sliding effects. Listen to tracks such as Weissensee on the first album [Neu!] and you’ll hear that.

I used it quite often for special effects and also more recently three years ago when I was asked to do a film score for a German director [Bastian Günther]. The film was called Houston. He actually had this wish: ‘Michael, could you use the old gear?’ So I dug up my old bass from the late 50s and the Ibanez. This old gear has a special magic.”

2. Amps Aren’t Always Necessary

“Usually, I work straight into the mixing desk. I record straight into the audio interface, and even during the analogue times, I would use a DI straight into an equalizer and compression system and then into the desk or onto the machine. Live, the guitar goes through my fuzz box and then through my volume pedal and then straight into my small mixer, which I have on my table on stage.

“From there, it goes to the front of house. I don’t play with an amp. My guitar player, Franz Bargmann, always asks for this typical Twin Reverb amp - which he loves - but, for me, it would change the sound if I went through an amp every time.”

3. Mistakes Can Be A Blessing

“In the 70s, there were some people around Forst [in Brandenburg, where Rother has been running a studio since 1973] who were musicians but who also built amps and speaker systems.

“One guy approached me and presented what he thought was a good copy of a popular fuzz box of the times, but it had a different sound and I liked it. You can hear it on all my albums since Deluxe [Harmonia’s second album, 1975], including my solo stuff, and also Neu! ’75.

I like surprises - when something happens and makes me want to follow that lead

“It was a big wooden box with delicate wiring, which was so unstable you wouldn’t want to drop it or take it on a world tour… so I asked my friend, an electronics-genius guy, to make a copy of it but in a tough metal box. He laughed and told me, ‘Those guys made a mistake back then!’ and I said, ‘Oh no, please repeat the mistake!’ He’s now made me two copies. Those original mistakes are so important to my sound.”

4. Relish In The Sonic Surprises

“I have three generations of [Korg] Kaoss Pads - the Quad, the KP3 and the KP2. They are similar but have different features. You can never reproduce the same treatment even if you try to memorise which effects you’re combining and how. What I enjoy about using them, especially live, is I can always be surprised and I am always looking for that, although not nasty surprises like monitors blowing up!

“I like surprises when something happens and makes me want to follow that lead. That happens very much on the Kaoss Pads and I send everything through them. Actually, I would love to have four hands and two heads so I’d be able to do the mixing and the playing and everything at the same time!”

5. Even Legends Can Lose Interest

I enjoy playing guitar live but that hasn’t always been the case. In the 90s, I lost interes

“I enjoy playing guitar live but that hasn’t always been the case. In the 90s, I lost interest, even though the guitar is my instrument and my first love. Nothing replaces the joy of playing guitar, but it’s not exclusive. I also enjoy messing with electronics and taking advantage of the sound creation and manipulation that’s possible on the computer.

“After Harmonia disbanded [in 1976], I only worked in the studio, but after 22 years of absence from the stage, I toured the US in 1998 with Dieter Moebius [Cluster, Harmonia] and I didn’t take a guitar along. I just had my notebook, a sampler and a keyboard.

“Later on, I saw these reviews and comments by fans, which said, ‘Well, it was great to see those guys, but what a disappointment Rother didn’t bring his guitar!’ and so I guess that made me think.

“Over the years you have to change, and maybe in two years there will be a new instrument, some new sound-creation tool that I want to jump into and maybe put the guitar aside for a while… but I think I will always return to the guitar.”

6. The Origin Of Inspiration

“As a boy, I lived in Pakistan for a time [early 1960s] and I was fascinated by the music I heard on the streets. Bands playing scales and rhythms I didn’t know and everything was so different, and the music didn’t have beginnings or endings, just a hypnotic thread.

When we started the first Neu! album, we were full of ideas, hopes, visions and optimism

“This sort of endlessness had a big impact. It’s not so much the scales, because I didn’t explore the Indian or Pakistani scales world at all - although Indian music can get me very emotional because of the beauty. For my own creation, I think it was taking more the inspiration of something that is so different from the Central European idea of melody and song.”

7. The Best Isn’t Always Planned

“With Neu!, Klaus [Dinger] was a brilliant musician and collaborator in the studio. When we started the first Neu! album, we were full of ideas, hopes, visions and optimism. We had four nights for recording and a full week at another studio for mixing. Any visions were hazy. I had some melodies, rhythmic ideas and ideas for things happening on top.

“The way we worked was like, ‘Okay, I’ll do one step’ and then the other one would look at the step and say, ‘Oh, that’s interesting, maybe I can put this step on top!’ That’s the way the process developed. It was random and fast, with not much time to reflect because we had this limited amount of studio time.”

8. Recognition Can Be Slow

“When I came to Forst with my guitar and I jammed with [Hans-Joachim] Roedelius for Harmonia, it was musical love at first sight. It was so clear with the combination of his fuzzy organ and piano playing and the treatments that he did. He offered a harmonic, melodic, rhythmical structure and backing, which enabled me to build the guitar around that and then we added more instruments.

I was upset and disappointed when the audience didn’t share my enthusiasm and love for that music

“Dieter Moebius joined and he was so talented at improvising. In the end, it was like cooking, with us all throwing in spices and surprising each other. That was how Harmonia worked.

“I was upset and disappointed when the audience didn’t share my enthusiasm and love for that music. I was surprised because I was sure, ‘Everyone must love this music - this is great!’ but it was ignored. People in Germany didn’t go for Harmonia at all. Maybe it was because there were too many details or whatever, but this changed about 30 years later. It’s like a gradual process and it’s still happening where people are catching up with Harmonia and there’s no-one who’s happier about that than me, because I always thought it wasn’t fair. I’m not saying we were brilliant, but we didn’t deserve that kind of rejection.”

9. Aim For The Unknown

“When it comes to musicians, I would hope what I create also leads to the spark of thinking that the idea behind the music is to steer away from heroes, to steer away from known ground and to discover something that’s not around.

It always makes me happy to hear people say, ‘You gave me inspiration to take some risks.’

“It always makes me happy to hear people say, ‘You gave me inspiration to take some risks.’ Back then, I could say, ‘I will forget about the pop music, the rock music, the American bands and the British bands and I don’t care about what is happening in Germany. I do not listen to Tangerine Dream or Amon Düül. I respect my colleagues of Kraftwerk and I respect my colleagues of Can, but they’re on a different path. I’m doing my own stuff!’

“It’s harder today because music is available from everywhere and everything is immediately shareable and accessible. And, also, we must not forget the spirit of the times. In the late 60s and early 70s, that spirit helped artists look for new fields and new expressions. There was something like a virus in the air and it was something that is not - to my knowledge - around in that strength any more.”

10. Play Beyond The Labels

“I don’t care too much about the expression ‘Krautrock’. I never liked it, but since it’s become a sort of technical term, it’s used in a more positive way than in the earlier days. In the 70s, being called ‘Krautrock’ was almost a rejection to us.

I don’t care too much about the expression ‘Krautrock’. I never liked it

“The idea, for me, was always to be different. I didn’t want to sound like anyone from Munich or Berlin or wherever. You had this huge box called Krautrock, but you had all these different artists who sounded very different.

“I’m not fighting the expression, though. I even just played for an event called ‘Krautrock Karaoke’ in London, which is funny! It was just about guys going on stage and jamming. I don’t have any better expression to offer, but look for the differences and accept that this is a box filled with lots of uniqueness. It’s like looking into the sky at night - you might think the stars and planets are very close together, but, in fact, they are millions and billions of light-years apart.”

For more news and further information on Michael’s projects, visit his official website.