Meet your maker: MXR at 40

Not Just A Phase

MXR, the maker of the Phase 90, is 40 this year. Although its reputation was founded on rugged reliability, the company has always been forward-looking in terms of tones, too. We talk to Jimmy Dunlop, Jeorge Tripps and Bob Cedro to find out what the future holds...

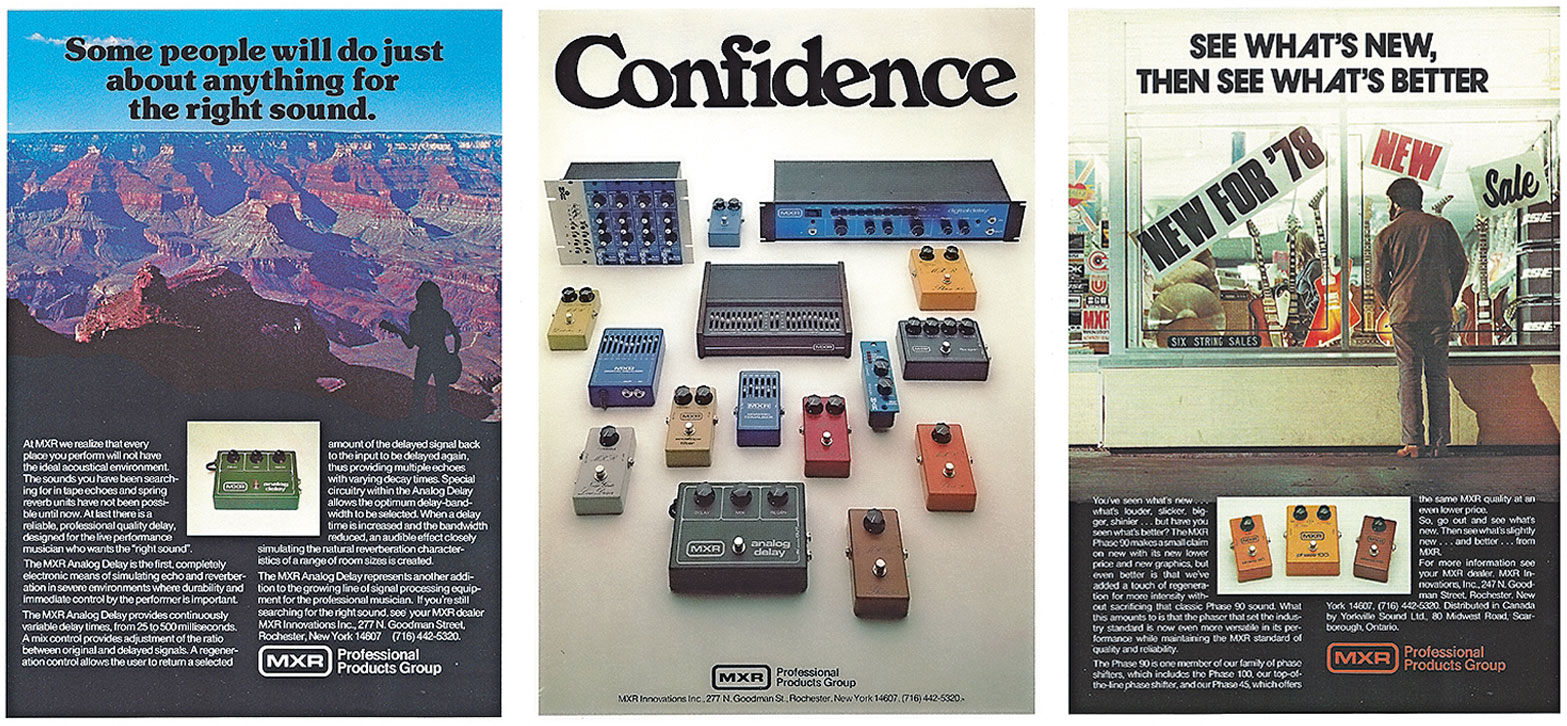

Simple yet tonally authoritative and tough, MXR pedals have been around for 40 years. Founded as MXR Innovations in 1974 in Rochester, New York, by audio techs Keith Barr and Terry Sherwood, the firm's colourful enclosures housed tones that would remodel the sonic landscape of guitar.

"I grew up playing MXR, and I never stopped" - Jeorge Tripps

From Larry Carlton's smooth, creamy solos with a Dyna Comp compressor to Van Halen's celebrated use of the Phase 90 to add movement and swirl to high-gain tones, MXR effects were arguably the pedal sound of the 70s. MXR's founders eventually moved on to new audio projects with Alesis and Whirlwind USA, and Dunlop acquired the brand in 1987.

Today, MXR pedals are more hot-rodded and modded than any that have come before, but maintain the marque's reputation for rugged effectiveness. So has life begun at 40? We picked the brains of MXR's Jimmy Dunlop, Jeorge Tripps and Bob Cedro to find out why they're having more fun with effects than ever before...

"The first MXR pedal I ever tried was a script-logo Phase 90 that I bought used for $40 in 1986," effects designer Tripps recalls.

"I grew up playing MXR, and I never stopped. When I started Way Huge Electronics in 1992, I used MXR as the role model. To be honest, I was more excited by the prospect of developing new MXR pedals than I was about resurrecting Way Huge," he adds with a grin.

Jeorge Tripps (left) and Jimmy Dunlop (right)

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It's a revealing admission that illustrates how MXR shook up the world of pedals back in the 70s. Thousands of young players were blown away by the tornado of phaser-drenched overdrive that Eddie Van Halen unleashed with MXR's Phase 90, which rapidly became an iconic effect. Four decades on, the block-colour enclosures of those early MXR pedals still look modern, minimal and cool, but a lot's changed too.

Today, Tripps designs new effects for both Way Huge [which has since been bought by Dunlop] and MXR, with the result that some of Way Huge's quirkiness has seeped into MXR's pedals, too, with the blessing of Jimmy Dunlop, son of Dunlop Manufacturing's founder Jim Dunlop.

"I gotta say, Jeorge coming in eight years ago... he was kind of the missing spice in our killer stew of creativity," Jimmy reflects.

"Because he did Way Huge and then he did Line 6, and then he said to me, 'Jimmy I don't want to do digital anymore, can I come work there, and let's do some amazing analogue effects?"

He could, and he did, and consequently the Phase 90 has some pretty wild siblings now: hot-rod 'boutique' pedals such as the M75 Super Badass Distortion or La Machine - a swampy blend of fried-transistor fuzz and octave-up aggression caged in a sparkling purple enclosure.

"I was always a fan of Way Huge... When Jeorge came in, I was like, 'Screw it! We need to have some more fun here too!'" - Jimmy Dunlop

"I love that pedal," Jimmy Dunlop says. "When we made it we were looking at Ernie Isley, trying to go for that sound. And then we started working with Billy Gibbons - and we were trying to put it in a box for him, but that took three years and we never brought it out. And I was thinking, 'Man, we have to bring out that pedal'.

"And it was kind of like 'La Machine'... did you ever see the movie 8mm? That's the name of the killer in that film. So we painted it purple in honour of Ernie Isley, and brought it out as kind of a Custom Shop deal."

Placed alongside classic MXR designs such as the workmanlike Micro Amp, La Machine is like a drag racer at a truck stop. But it's part of a conscious move to inject some extra attitude into MXR's range of effects pedals without losing sight of what made them popular in the first place, says Jimmy Dunlop.

"The funny part about pedals like the Custom Badass and the Super Badass is that when Jeorge Tripps started working with us, I was always a fan of Way Huge," Jimmy recalls.

"And Jeorge was always a fan of MXR. And I was always envious that Jeorge could come out with a Swollen Pickle or a Red Llama, because I kind of had my hands tied because I was MXR. And I thought, okay we're doing a Phase 90 and a Phase 100... and we had to kind of stick with that traditional utilitarian vibe. And then when Jeorge came in, I was like... screw it! We need to have some more fun here too - so let's see what we can get away with, without pissing off the MXR purists. That's kind of where we're at."

Tough love

All the same, certain family values are common to all MXR pedals, senior engineer Cedro argues.

"We're very conscious of where it all started and why it started. And, actually, the philosophy they had in the beginning worked really well: they designed utilitarian pedals you could drop off the end of a truck that were simple enough you didn't need a manual to get going and be inspired. Because - let's face it - guitar players have a short attention span... I'm one of them!" he adds, laughing.

Ruggedness has always been one of the hallmarks of MXR pedals, and since Dunlop bought the brand, they've put a lot of time and thought into continuing this trend...

"It's funny, because when you think of a pedal, you think of what can go wrong with electronics," Bob considers. "But the thing that really goes wrong with most of this gear is the interface: they call it a footpedal for a reason. It's a stompbox - so right there it's gotta have the durability of withstanding abuse - and musicians, you know, they throw gear in the back of a truck.

"And so the first thing that we did to make MXR pedals last was to create a new [foot] switch, using our knowledge of how switches work and all the failures that can happen. We worked with a company that makes switches and approached it from the ground up again."

"The other thing is the jacks," he continues. "We've actually created our own jacks now - we had a manufacturer that we worked with for a while and we just weren't getting the quality that we needed - so we said, 'Hey, we gotta make our own jacks'.

"So we specified the materials, the fabrication process.... but once again, those mechanical things are some of the most important factors as far as durability goes."

Life after 40

It's praiseworthy attention to detail, but in a world where Chinese-made clones of classic effects can be bought for $25 (cheaper than the used Phase 90 Jeorge Tripps bought in '86) does the idea that players might buy ultra-cheap pedals and simply replace them if they break keep anyone awake at night? Or does MXR's rigorous approach mean they'll always appeal to a certain kind of player?

"At the moment I think that players are kind of coming back to the analogue world" - Jimmy Dunlop

"Well... how about this?" asks Jimmy Dunlop carefully. "I know it's out there. But I would go crazy if I thought about it all the time. I know that those guys... the quality of what they're making is coming up.

"But obviously we try to do everything in the USA, and I just think that our innovation and attention to quality is pushing harder, because I hate to say this, but we have so many musicians here that are also making pedals for us and I don't know that they're doing that over there. And, probably, that's as far as I want to go with that one,"

With the big launches of the January NAMM show just around the corner, everyone's rather tight-lipped about what pedals MXR will release next, but what direction do they feel effects design is going in more generally? What tones are players looking for at the moment?

"I'm a fan of just really gainy, dirty fuzz," says Dunlop. "That's where I think we're at right now - I love it. I like to hear that floodgate of power from the guitar."

"Well, my crystal ball's been out for a while now," Cedro adds wryly, "I've been meaning to get it fixed [laughs]. But we work with a great bunch of musicians who are in the trenches and causing trends, so luckily we kind of have our ear to the track... And at the moment I think that players are kind of coming back to the analogue world - or at least to digital effects that are more analogue-like. That's the trend, for me."

What about the current rise in retro multi-effects, such as T-Rex's SoulMate or the three-in-one Tone Tattoo pedal by Electro-Harmonix. Would MXR ever consider putting some of its classic pedals into a similar analogue multi-effect unit?

"Never say never, but I've always felt that single pedals are just the coolest thing ever," Dunlop says.

"Because you can mix, you can match, you can put things in front or behind and you just have so much freedom with single boxes. And I don't know that with analogue... I just think the circuits are big, and it's not like digital - it's not all burned into one chip. You get into how big a board has to be to put out different types of effect, and have it all on one casting. To me, it takes away the simplicity and the beauty of just that one pedal with three knobs. I like to mix and match and I like the freedom of that."

Talking to all three men, there's a sense that it's a pinch-yourself thing that they've wound up making MXR pedals; that it's not just another brand with a bit of heritage to tip a nod to - but rather like they're finally getting to drive a car they admired as kids. There's not so much reverence for the backstory that it'll stop them having some fun, however.

"We have a lot of cool people at MXR and Dunlop," Jimmy Dunlop concludes. "And if you see what people are doing with boutique effects... well, we live in that zone. So for us to not be hot-rodding our pedals, our designs, would be crazy. We have a little more personality than to just stock pure orange phaser pedals."

Three of a kind

Effects design guru Jeorge Tripps talks us through three of MXR's classic 70s designs, each of which is still in the range today, and explains why they've remained pedalboard favourites for so long.

Phase 90

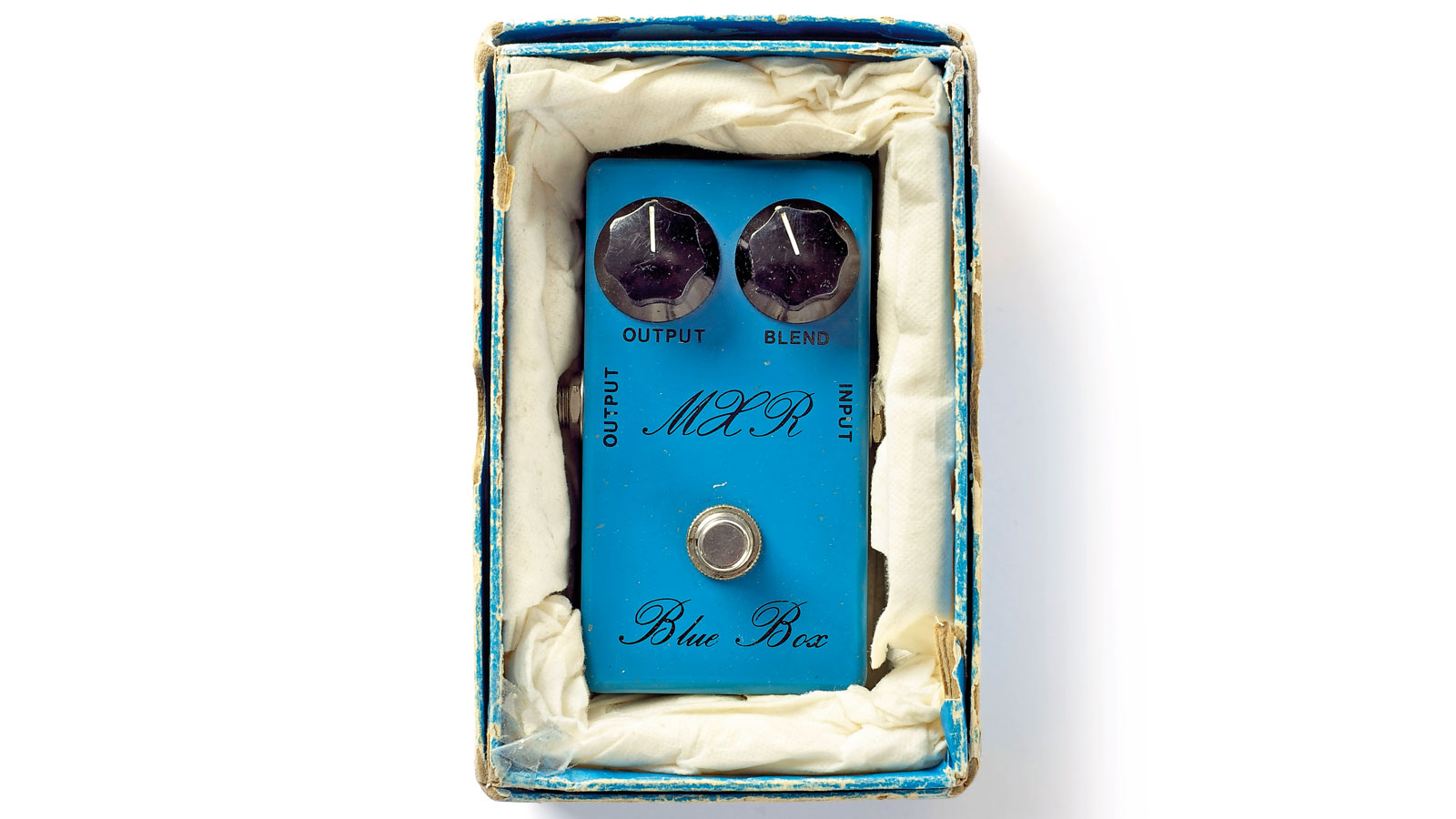

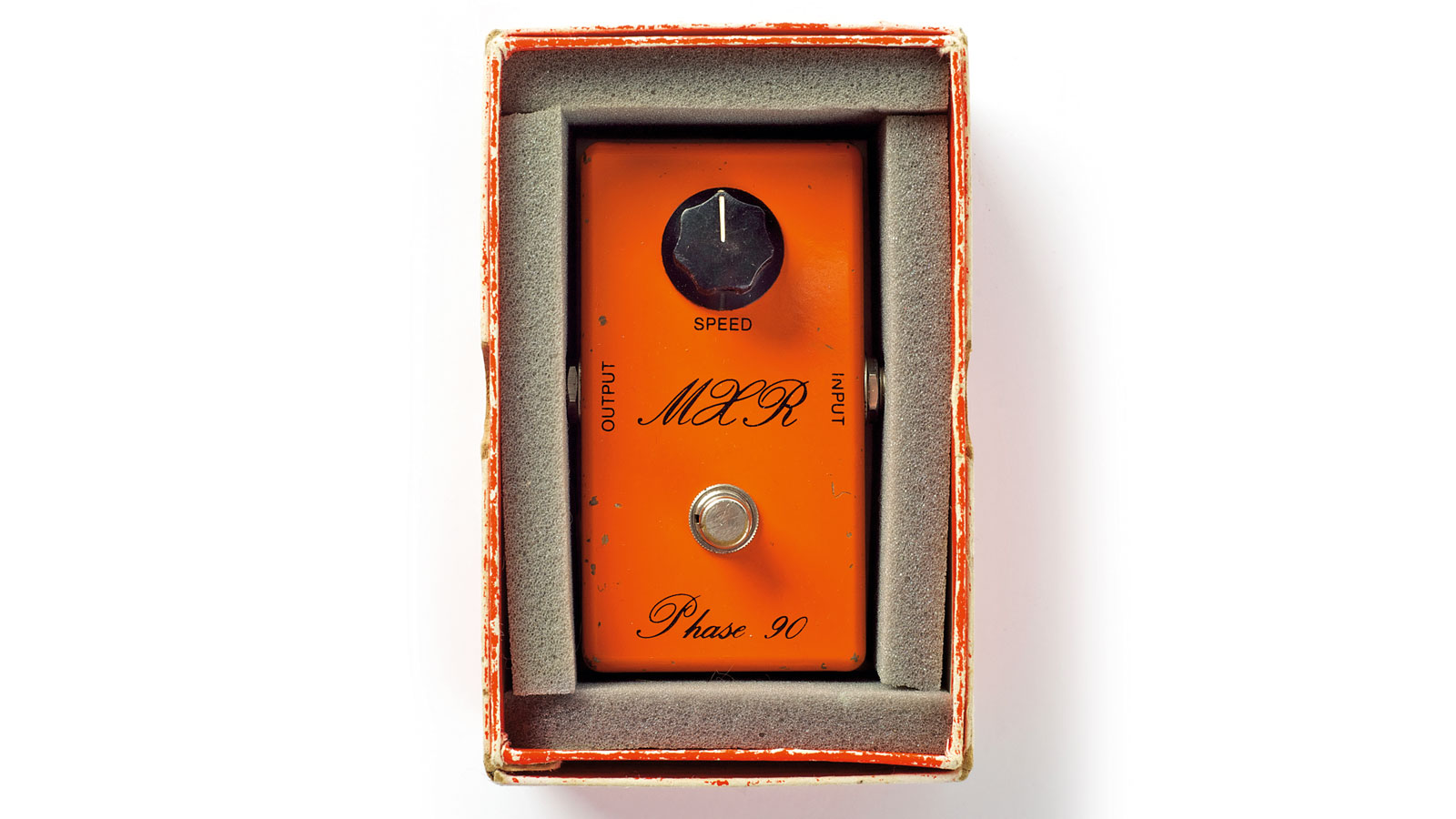

The Phase 90 and its descendants are MXR's best-selling pedals. Launched in 1974, and designed by Keith Barr, this four-stage phaser featured a single knob to control the rate of the effect.

The original 'script-logo' unit used 2N5952 JFET transistors in combination with six 741 op-amps (replicated in the MXR CSP-026 Handwired 1974 Vintage Phase 90) to generate its hallmark phasing tone, a spec which was later revised several times, including under Dunlop ownership - more recent versions feature three dual op-amps, for example.

The script logo was changed to the block logo in 1977, while offshoots such as the Eddie Van Halen Phase 90 have a redesigned circuit.

"Besides sounding great, the Phase 90 is simple and easy to use," Tripps observes. "And it's been used on so many classic recordings - the Van Halen records, but also Led Zeppelin's Physical Graffiti, Pink Floyd's Wish You Were Here and many others. Musicians have used the Phase 90 to change the sound of music. It's the iconic example of the phaser effect."

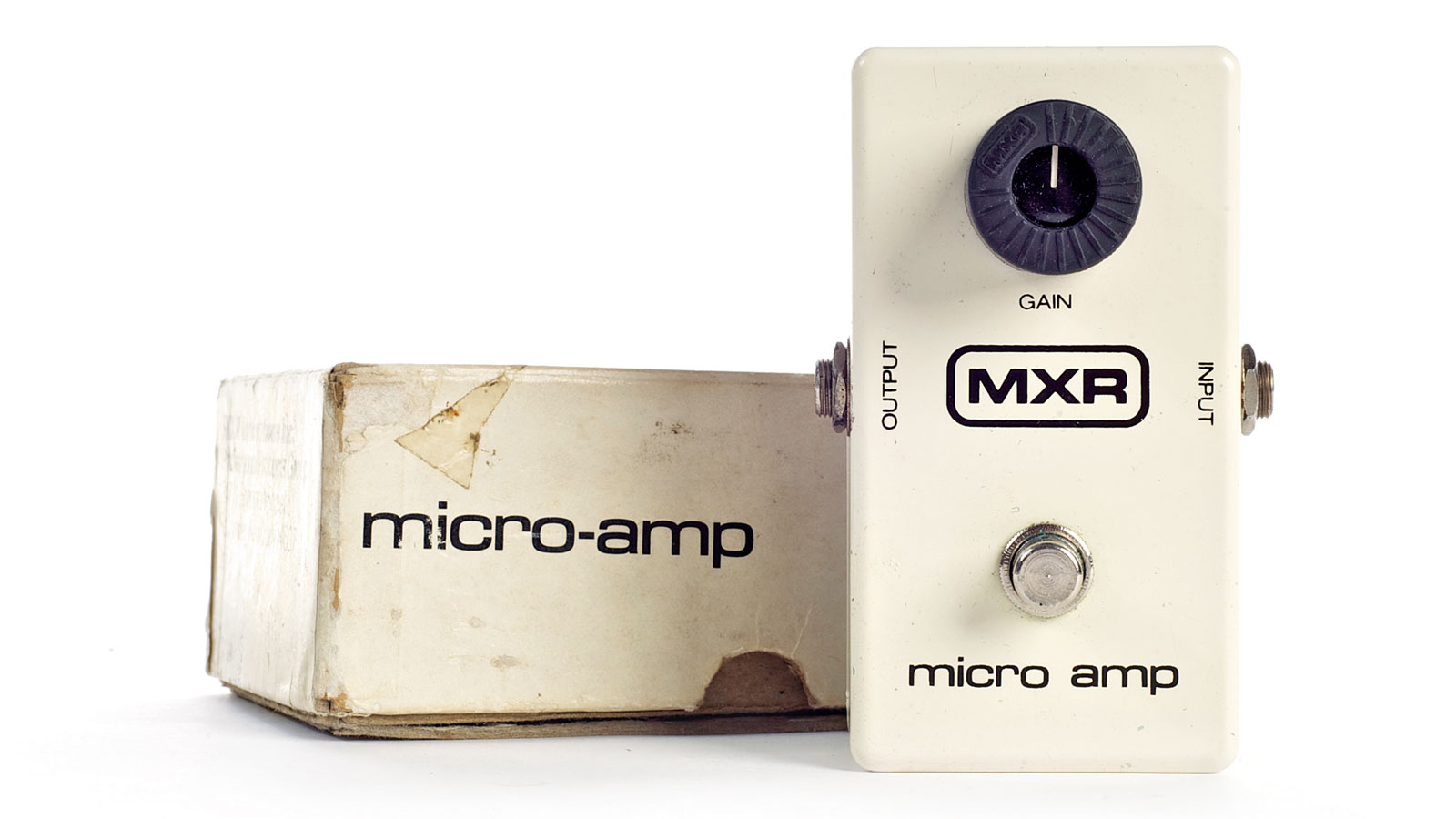

M133 Micro Amp

This classic clean boost is a close non-distorting cousin, of MXR's Distortion+.

Released in the early 70s as part of MXR's Reference Series, it was originally issued without an on/off LED, or the means to accept an external power supply. Its TL061 op-amp was consequently chosen for its low current draw. The most recent Micro Amp+ adds EQ and a lower-noise circuit to this already classic design.

"It's an amazing boost pedal that is very transparent," Tripps says. "So it basically amplifies your guitar's tone and hits the front end of the amp to get distortion without colouring the voice of either."

Distortion+

Ask Tripps what his favourite vintage MXR pedal is from the point of view of circuit design and he doesn't hesitate.

"Well, I would have to say the Distortion+," he explains. "As far as I know, it was the first pedal that used an op-amp and hard-clipping diodes to create the gain type we generally refer to as distortion, as opposed to overdrive and fuzz. Dirt pedals produced before '72 to '73 were generally some type of square-wave fuzz effect, such as the Fuzz Face."

The Distortion+ was one of the first pedals made by MXR, dating back to 1973, and was designed by Keith Barr. The enclosures of the earliest script-logo units were made by third-party company Bud, and these are now highly collectible.

Script-logo pedals, which utilised the LM741CN op-amp, sound tonally distinct from the block-logo units featuring the UA741CP op-amp. A higher-gain variant from the 80s Commande series was simply called the 'Overdrive' model, while the 2000 Series model of 1983 featured a substantially redesigned circuit.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

“Built from the same sacred stash of NOS silicon transistors and germanium diodes, giving it the soul – and snarl – of the original”: An octave-fuzz cult classic returns as Jam Pedals resurrects the Octaurus

“For guitarists who crave an unrelenting, aggressive tone that stands out in any mix”: The Fortin Meshuggah head is the amp every metal player wants – now you can get its crushing tones in a pedal