Marty Stuart talks Telecasters, Fabulous Superlatives and new double album

"When we record, we barely talk about anything – we just start playing"

Marty Stuart talks Telecasters, Fabulous Superlatives and new double album

Just because Marty Stuart was less recognized for his hot picking than his strutting showmanship during his early 1990s hillbilly-rocking commercial peak doesn’t mean that musicianship hasn’t been essential to his identity. Proof of his teenaged-prodigy era is easy to find on YouTube: In a ‘70s Porter Wagoner Show appearance, he’s the pint-sized, prepubescent, mandolin-playing, tenor-singing employee of bluegrass legend Lester Flatt. And that wasn’t even his first pro gig – he’d already spent weekends touring with The Sullivan Family, a bluegrass-gospel outfit.

These days, Stuart’s band is The Fabulous Superlatives, one of the most admired outfits in Nashville, rounded out by singing drummer Harry Stinson, singing bassist Paul Martin and Stuart’s nimble Telecaster foil Kenny Vaughan. They’re a compact group with a lusty, harmony-rich, hard-twanging, dual-guitar attack and a distinctive personality, not unlike Buck Owens’ Buckeroos back in the day.

Stuart and co. devote half of their new double album, Saturday Night & Sunday Morning, to down-home gospel grooves from an array of black and white traditions. “When we put the Superlatives together,” the front man explains, “the way we got to learn to sing together – and the way we learned about each other musically, spiritually and professionally – was gospel songs. I brought the music of The Staples Singers and Flatt & Scruggs, Bill Monroe and the Stanley Brothers. Kenny brought Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s music. Harry brought the Swan Silvertones and the Dixie Hummingbirds’ music. Paul came to us from Oak Ridge Boys world – so, southern gospel. Gospel music was the way we figured it out.”

How would you say that those different gospel influences come through on the album?

“We kept listening and we kept singing. But when we started writing our own tunes, a lot of that, it just kind of happened. I noticed when I would write songs with Harry, maybe they were a little bit more introspective. And Paul, his musical arrangements are very sophisticated. And when Kenny and I write, it’s always more from a joyful place, Boogie Woogie Down the Jericho Road-type gospel music.

“A kid told me one day, ‘When I listen to you guys play gospel music, I don’t know whether to drink beer, worship or fight.’ I said, ‘Man, that’s the greatest compliment you could ever have given me.’

“We’ve been together as a band enough now, and been through so many musical waters, that whatever we do, it comes out sounding out like the Superlatives now. You can tell where we’ve probably looked at it or saw it or heard it the first time. But at the end of the day, it sounds like us now.”

The Superlatives' twin-Tele sound

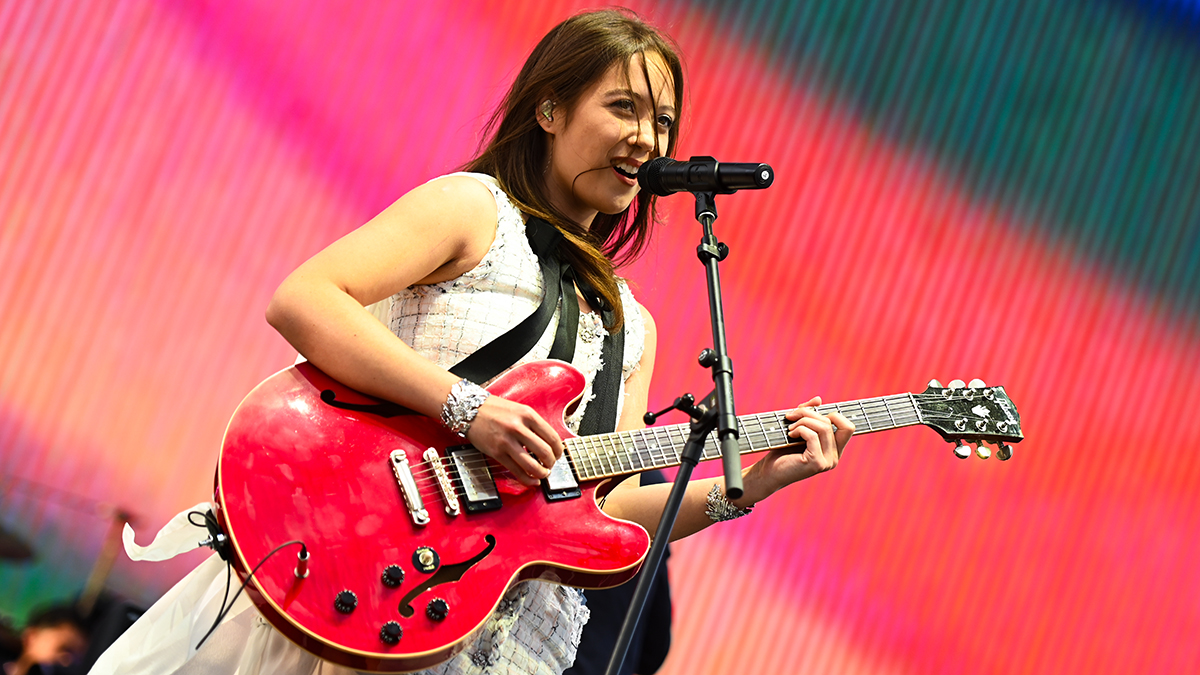

Photo: The Fabulous Superlatives (from left) Harry Stinson, Kenny Vaughan, Paul Martin and Stuart

You go back a ways with The Staples Singers. You recorded The Weight with them for that album Rhythm, Country & Blues that brought black R&B performers and white country performers together 20 years ago. Then they bequeathed Pops Staples’ guitar to you, and you’ve got that and Mavis Staples’ singing on here. What debts do you feel like you owe to the Staples’ music?

“To begin with, that performance of Uncloudy Day was an absolute recast of their blueprint version on Vee-Jay Records back in the ‘50s, one of their first recordings –which, to me, still stands as one of the greatest offerings that you could have to the American gospel songbook.

“Going way back to 1964, those three Civil Rights workers, Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman, were murdered in my hometown, Philadelphia, Mississippi. [The Staples’] version of Uncloudy Day became an anthem down in that part of Mississippi. You would hear it playing on the radio. You could hear it coming out of people’s homes over in the black part of town. Uncloudy Day, the Staples’ version, just became a part of life and a part of the atmosphere down there. I never forgot it, and I never forgot the power in it. I never forgot the way it made me feel. When we had a chance to do this with Mavis, I wanted to recapture that as close as I could. And I think we did it.”

The Telecaster has been a part of your sound throughout your solo career, but you doubled down on it by drafting Kenny Vaughan to play alongside you. I can’t think of any other active band that has a more potent Telecaster attack than yours.

“You’re right. It’s a pleasure to go to work every single night. When we record, we barely talk about anything – we just start playing. If you push his fader up and my fader up and everybody else out, we never step on each other. It’s like a tapestry. It’s just one of those once in a lifetime things. It doesn’t happen very often.”

Your dual-Tele dynamic brings a lot of energy to the live shows. There’s the live wire sound of that guitar, first off. Then there’s the way you two egg each other on.

“It’s one step shy of a chainsaw. [Laughs] With reverb.”

When did you buy the Tele you call Clarence from Clarence White?

“1980.”

So you’ve had it through your entire solo career.

“Absolutely.”

It came with a B-bender. Didn’t you also add an E-bender?

“I did. Ralph Mooney, the steel player – I was out at his house one night, and he’d played this song called Drink Up And Be Somebody with Merle Haggard. And it had the most unique, little, wacky steel part. I said, ‘I wish my guitar would do that.’ He said, ‘It will. Bring it out here in the garage.’ And about four hours later, the sun was coming up and I went, ‘Well, it’ll do that now.’ So Ralph Mooney put that pedal on. That’s the only thing I’ve ever changed about that guitar.”

Everybody's a star

You own guitars could be artifacts and showpieces, considering the history they have with original owners like Hank Williams or Clarence White. But you actually play them.

“Well, they were made to be played. We take good care of ‘em. I have a big insurance bill, and I make those guitars earn their keep.”

Which guitar began your tradition of naming them for the musician who’d owned them?

“Clarence probably. Actually, it was Lester’s guitar. It was Lester’s and then Clarence. There’s Lester. There’s Carl Lee – that’s Carl Perkins. There’s Pops Staples. And there’s Clarence and Connie Smith. There’s George Jones. There’s Merle. Luther –Luther Perkins. I’m blankin’ at this point.”

Don’t you have a Mick Ronson guitar, too?

“Mick Ronson! That’s right.”

Every time I’ve seen you perform with the Fabulous Superlatives, you’ve featured each and every one of them. Paul and Harry will each step forward and sing lead for a song, and Kenny may do that or tear into an instrumental. Why is it so important to you to spotlight your band members individually?

“Well, that’s the way I was trained. I mean, going back to the Sullivan Family Gospel singers. When I was a kid, I would watch the Flatt & Scruggs show [on TV], and they would feature everybody in the band. All the Foggy Mountain Boys were stars. The same with the Johnny Cash [TV] show. When I went to work with the Sullivan Family, that was the way it was – it was like an ensemble. Everybody got a turn at the microphone. And when I went to work with Lester, nothing had changed; he made sure everybody on the stage had their moment. Same with John’s band. Everybody had a turn in the spotlight.

“But especially this particular band – everybody’s the star. When we tour, Kenny has an audience that comes to see him. Paul has an audience, and Harry has an audience, too. They all have individual fans as well as just a band in general. I love that.”

And they’ve each done plenty in their musical lives before you all formed this group.

“Absolutely. And that is to be respected and not hidden.”

On gospel instrumentals

What difference does it make that you did all that dues paying as a sideman with Lester Flatt, Johnny Cash, Vassar Clements and others before you stepped out as a front man?

“Well, in Native American society, a kid starts out as a scout, and then a water boy, a brave, then a warrior. And if it’s truly meant to be in his heart, he becomes a chief somewhere along the way. But by the time you get to be a chief, it’s understood what it takes to be a chief. I don’t think it’s a lot different from that. I’m so happy I got to start off as a musician, working for other people and doing the songwriting. I had to make myself learn to sing. I think it makes the journey so much more interesting.”

Apprenticing as a sideman is a more common route for a young picker coming up in bluegrass.

“This town is full of pickers. Every recording session check and every dollar matters when you’re trying to feed a family, and you’re doing it by playing music. Every compliment matters; every step along the way matters. What it really did more than anything, it taught me how to treat people. Because I was treated so good by Lester Flatt. I was treated as a son by Johnny Cash. It taught me that you treat people with dignity.

“And in the case of the Superlatives and the whole team – not just the band, but the crew – those guys are like statesmen. They represent not only me, but they represent themselves, their families and this town and the culture of country music with such high regard. I love watchin’ the respect that they get when they walk into a room.”

There are instrumentals on the gospel half of the album, Good News for one. Lyrics are usually the carrier of spiritual content, and those aren’t in the picture. So what is it that makes it a gospel song?

“Haven’t you ever been to church when they pass the plate? [Laughs]”

Well, sure.

“Music in the church doesn’t always have to have words. Sometimes a song says a lot without saying a word. In the case of Good News, it just didn’t need any words. It needed joy. I looked at the album at that point and said, ‘We need something joyful. It doesn’t have to last very long. And Good News was here in about 10 minutes. We were all laughing like teenagers, like we just learned to play a surf song or something.”

I was just playing the devil’s advocate. I’ve certainly heard music speak without words. In fact, placing all the emphasis on lyrics is the kind of thinking that separates mind and spirit from body. And I don’t think that’s what you intended by placing Saturday night alongside Sunday morning.

“Right. …We have found the very best in both genres, that works day after day, night after night and speaks to the heart, makes you think, makes you wanna dance – and makes a smile come on your face and lightens your burdens.”

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)