Mark Knopfler on new solo album Tracker

A world-exclusive guitar interview

Introduction

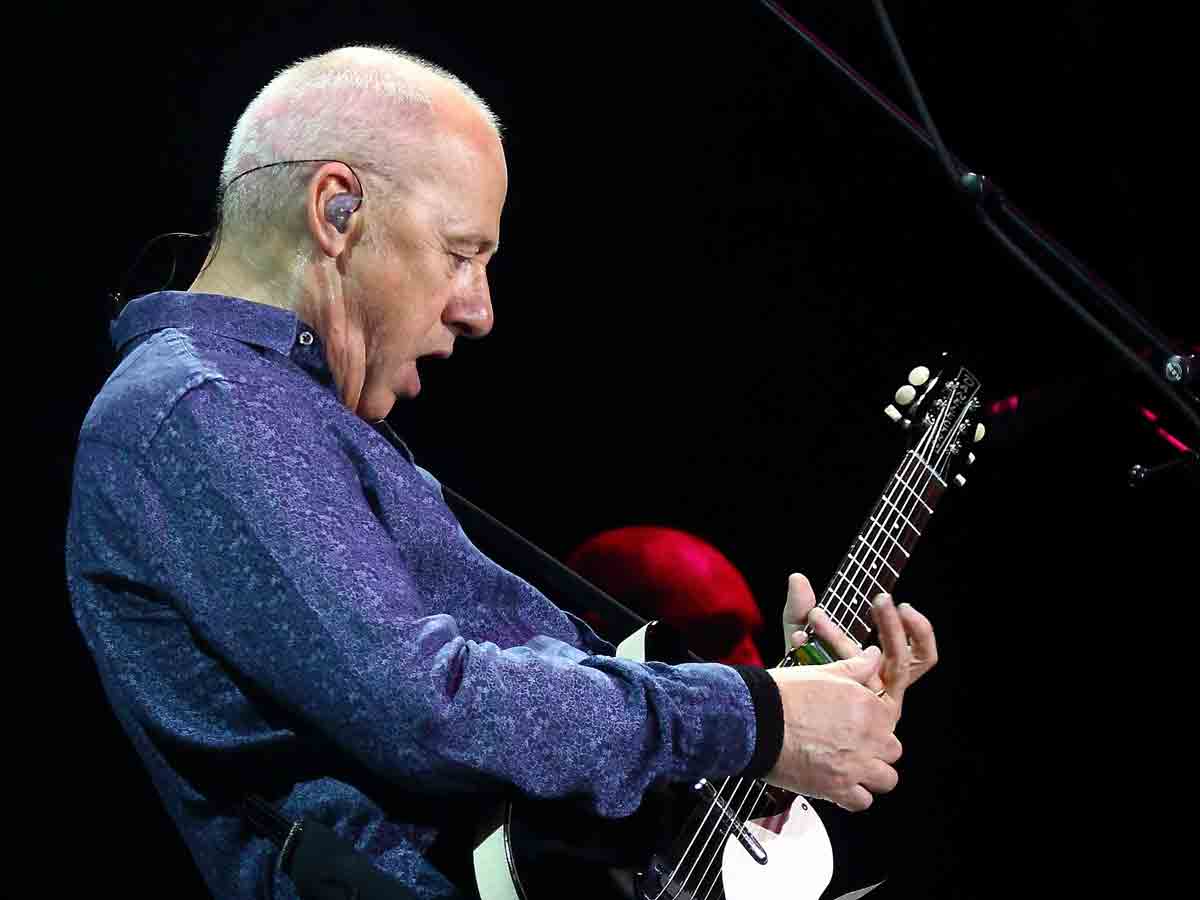

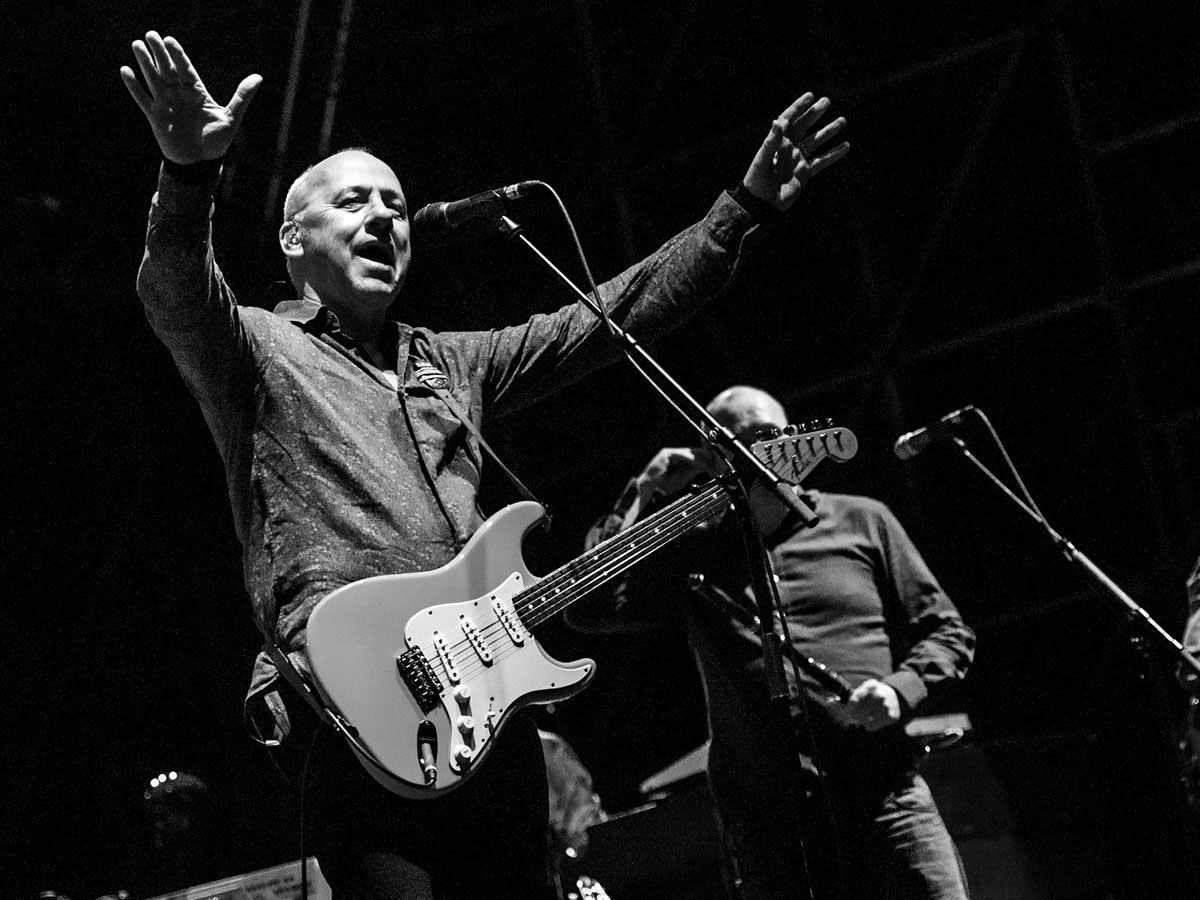

Mark Knopfler’s covered a lot of miles since the days when he walked the Telegraph Road. His new solo album, Tracker, is an essay in understated, eloquent playing - but it’s the songs and the characters that inhabit them that linger in the mind long after the record has stopped turning.

In a world-exclusive guitar interview, we joined Mark - one of the most down-to-earth rock stars you could hope to meet - at his London studio to talk about everything from songcraft to slide technique, amps and old archtops.

It’s a cold, bright morning at British Grove, Mark Knopfler’s big, airy studio in West London. Outside, traffic angrily inches forward on a choked arterial road, but inside it’s a haven of hospitable calm as we wait for the man himself to arrive.

Lots of old wood

In the corner stands a ’58 Les Paul Standard - a real one - with a plain top and a sherry-red tint still lingering in the Sunburst. There’s a fireplace and a long oak table; yards of neatly varnished floorboards. It’s all very low-key but, undeniably, the haunt of a guy who’s sold one or two records in his time.

And, without any fanfare, here he is, greeting us with a handshake and a steady, cautiously friendly gaze. He’s just come from a Pilates session, a discipline he says he gets a lot of benefit from, which quickly leads us on to a discussion of how muscle tension can stifle your playing.

Relax

“I’m still learning to relax my left arm, when I’m playing,” he says. “The more you can learn to relax that left arm, the more fluid you’ll be. If you tense up, you’re just gonna slow down. And for a long time I played that way - and I used to get pain all down my forearm. I used to play Sultans... like that a lot. It’s just habit. Getting the urgency into the playing gets translated into tension, unfortunately. But you’ve got to stop associating emotion with tension.”

Tension. The Zen-like calm of British Grove studios seems calculated to reduce it to a background hum, like the traffic, and leave Knopfler free to be creative in his own time, on his own terms. The colossal success of Dire Straits’ Brothers In Arms album in 1987, which sold 30 million copies, must have been giddying, even troubling, for a musician who today prefers to go unrecognised in the street.

It sold and sold, and as it did Knopfler’s thoughtful writing and richly melodic playing were reduced, by the shorthand of fame, to thumbnail icons in the popular imagination: the headband; the intro riff from Money For Nothing; the shining ’37 National Style O guitar on the album’s cover that looked as if it was being thrown into heaven by an unseen hand.

30 years later

Nearly 30 years on, Knopfler is about to release his ninth solo album, Tracker. Tender and downbeat, the songs are a portrait gallery of people and places: odd nooks and corners of life as it’s lived by deckhands and writers, penniless musicians and Bentley-driving chancers.

With far less fanfare than in the Straits years, his solo albums have sold in their millions and, arguably, it’s Knopfler’s preference for a (relatively) down-to-earth lifestyle that means his music still connects.

"You get to that kind of age and you have to follow something through to finish it. You’re not necessarily sure of what it is that you’re going after"

He’s got the same eye for character that made the London nightclub life in Sultans Of Swing come to smoky, jostling life, but the writing on Tracker seems to have acquired, with the years, extra patina and depth like the checked lacquer of an old guitar.

“You could see it in terms of time - tracking time,” Knopfler says of the album’s title. “You get to that kind of age and you have to follow something through to finish it. You’re not necessarily sure of what it is that you’re going after. But some sort of instinct leads you to the songs. And then you have to follow them down and finish them. So you’re the one that brings the stuff back, who’s tracked it down and got it.”

Character forming

The album - co-produced by former Dire Straits keyboardist Guy Fletcher - features top-drawer performances from an exceptional band, and from Knopfler himself, who sounds immersed in its sparse but warm soundscapes. When he takes a lead, it’s generally just a few judicious notes, perfectly placed.

“One of the things you find out over time is that if you’re choosing between a few different passes over a song, you learn to go for the one with fewer notes,” he observes. “It usually says more.”

Likewise, the subjects of the songs themselves - ranging from the Newcastle poet Basil Bunting to the broke-but-happy London musicians of Laughs And Jokes And Drinks And Smokes - are all brought to life with understated skill.

“I certainly have a lot of songs that take their time putting their hand up"

“The characters that I’m interested in are usually not sorry for themselves,” he explains. “If you’re talking about a retired navvy, or you’re talking about a young man who works on a barge who’s alone at Christmas time in a strange city, they’re not sorry for themselves. You’ve just got to watch for being sentimental about it. You’re interested in the truth.”

Wheat from chaff

Does he reject a lot of songs? Or does he just turn material over in his mind until he finds a way to make it work?

“I certainly have a lot of songs that take their time putting their hand up. So what I’ll do is I’ll just look at them every now and again. Just drop in on them, you know? And see if I can make them happen. Or see if anything can happen. And sometimes something does and sometimes it doesn’t.

“And I’m not sure if it’s part of the enjoyment of it, but it’s the mystery of it that some things just happen in their own time. And they manage to stand up and go out into the light of day. But I don’t worry too much if a song isn’t wanting to leave home just yet. I suppose what I ought to do is just delete the damn thing, but I don’t [laughs].”

Tracking Tracker

The album abounds not only in memorable characters, but timbres, too. Most of the amplified sounds live in that just-breaking-up zone in which all the clarity of clean tone is retained, but with a cushion of extra warmth and grit to lend character to each phrase, notably on standout track Basil. It’s a tone some will know from the intro to Brothers In Arms, almost a signature sound. What amps did he turn to for the sessions?

“There were various amps. With something like that, you’re talking about the Les Paul through something like the Reinhardt Talyn, which is a great amp that Bob Reinhardt built for me. Also Ken Fischer, who built the Trainwreck amps, made me a Komet before he passed away, a fantastic thing that he christened ‘Linda’ when he built it. And I think he wasn’t 100 per cent happy with the way Komets then went on to be. But this one was personally built by him.

"For clean tones I’ve been using the Tone King Imperial a lot. And I use the rhythm channel for that, not the lead channel"

"It’s extraordinarily loud, so for stage you’d have to find a way of calming it down. Because it’s just such a beast. But in the studio, of course, you can just let her rip. That’s a fantastic-sounding amp.

“And for clean tones I’ve been using the Tone King Imperial a lot. And I use the rhythm channel for that, not the lead channel. I always go into the rhythm channel to play lead on it.

"It’s very, very clear. For that kind of sound, like the one I use on Beryl, with a Stratocaster, it was always going to be a toss-up between the Tone King and my old brown Tolex- covered Vibrolux.

“But on the road, I was playing slide through the Tone King as well - it’s great. And when I was playing with Bob [Dylan], on his sets, I would just go straight into the little Tone King. It’s a killer amp.

"And Mark Bartel has made a new one [the Mk II version], which I tried yesterday and it’s great - it’s right up there with my old one, I’d say. So that will be coming on the road with me. And I suppose Richard [Bennett, guitarist in Knopfler’s band] will have one, too, because they’re terrific amps.”

Slide rules

Another striking feature of the album is how much slide playing there is. It's something Knopfler says he's enjoying more and more with time, adding that he made a few minor breakthroughs in his slide technique during Tracker's recording sessions.

"Early 60s Strats are great, and I don’t think they’ve ever got much better than that"

“I’ve been using the white [’64] Strat for slide,” he explains. It’s just been beautiful to play, I realised I could fret notes a little bit in front of the slide, too. And that sort of just fell into place. I never thought I’d be able to do that.”

Despite his association with vintage Stratocasters, Knopfler says he doesn’t make a fetish of period-correct details and is content if he can play a decent Strat that has a few of his preferred features.

“I think I get on better with rosewood fingerboards. Although having said that, I like heavy strings on my old ’54: I hit them with a pick for tone and use the tremolo arm for that style of playing. But for most of the ordinary stuff I don’t. I think they’re all much of a muchness really. I don’t think it matters too much.

"Early 60s ones are great, and I don’t think they’ve ever got much better than that. I think my signature Strats have been good and that’s what I use. It was just a good combination of the bits they were making - because they don’t incorporate anything particularly special.”

Tuning

Does he play electric slide in standard tuning?

“No, never - I’d like to and I ought to really get on with it. Because I love the possibilities of that. But normally it’s either the open G tuning or an E tuning. But playing slide in normal tuning is something that I’m really looking forward to getting into. But I’m always doing something else [laughs].”

It’s gratifying to hear that one of the world’s best guitarists can’t, like most of us, find enough time in the day to advance his technique as much as he’d like - although you’d have to say he seems to have muddled by okay, so far.

“The slides I use are a glass composite material – they’re the best ones I’ve ever used"

“The slides I use are a glass composite material,” he continues. “But they’re the best ones I’ve ever used. And I had a beautiful one that I dropped and smashed, but the other ones that they’ve replaced them with are just about as good.

"My favourite ones ever so slightly taper; the hole is slightly offset, so you can have different thicknesses. But I never really bother about that too much, I just put it on and play it.

“And the Coricidin bottle slides, I’ve tried them and they're good, too, but they're a little bit lighter. Originally I started with a lot of steel and brass and my dad, bless him, he made some from brass tubing. He made me first slides. And so, every now and again, yeah, a piece of steel will do it - but I think I prefer these ones that this company Diamond Bottlenecks makes.”

Archtop aficionado

Touching on slide, we ask if the well-known ’37 National Style O Resonator that has been with Knopfler ever since his formative days playing blues with Steve Phillips in Leeds made it onto the new album.

“It nearly always does. I don’t know whether it did this time but I tell you what has, on a couple of the songs, is my mid-30s D’Angelico, and that’s just been a fantastic guitar to record with. It’s an amazing thing, sound-wise. But yeah, the National would always get on things. Sometimes, it just occupies that ground between a piano and a guitar.

“But I love using archtop guitars on records, too. They just sound so good. And in fact I picked the D’Angelico on a song called Silver Eagle and it sounds like a flat-top with a pick on it - but it’s just that D’Angelico speaking. And on River Towns I’d be strumming that, too. But yeah, those mid-30s ones are just unstoppable. As good as anything can be.”

His praise for archtops, often under-used in a purely acoustic role, stems partly from his admiration for master luthiers in the grand old Italian archtop-building tradition, such as New Yorker John Monteleone, whose patient skills Knopfler paid tribute to in the song Monteleone from the 2009 album Get Lucky. Today, Knopfler worries that the craft is so exacting that it may die out for want of fresh blood.

The importance of apprentices

“It’s a shame. John Monteleone is such a brilliant builder but he doesn’t have an apprentice. Because D’Angelico used D’Aquisto as his apprentice,” Knopfler explains, speaking of the two most celebrated makers in archtop history.

"I think this is the story of modern times: when you get somebody of that level of excellence, they can’t find the youngsters capable of being disciplined up to that level”

“And D’Aquisto would do repairs when D’Angelico didn’t want to be bothered with repairs - when he wanted to be getting on with his own ideas instead. And so the same thing happened with D’Aquisto: when he wanted to get on with his own ideas, he gave his repairs to John - Monteleone being the only one he could trust to do them properly, to his standards.

“And I was asking John about that. I said, ‘Who’s your apprentice?’ Never found him. And I was also asking [luthier] Stefan Sobell about that in Northumberland a couple of years back. There was a young guy making a guitar in Stefan’s workshop, and I said, ‘Is this your apprentice?’ and he said ‘Oh, no - he’s a perfectly nice young man. But no, I’ve never been able to find anybody.’

"And I think this is the story of modern times: when you get somebody of that level of excellence, they can’t find the youngsters capable of being disciplined up to that level.”

Song makers

You can hear in Knopfler’s strong performances with these archtops an echo of his early days playing trad-blues on unyielding acoustics in pubs of the North.

Knopfler’s a naturally left-handed musician who grew up playing the guitar right-handed, so that in itself has shaped his style to a degree, meaning he’s not daunted by vintage guitars that require some old-fashioned elbow grease.

"When I was little, I was [miming] playing left-handed guitar with a tennis racquet and my older sister, Ruth, turned it round"

“Oh yeah, there’s no question that playing cheap acoustics and Nationals certainly played its part,” he says. “Because they’d usually be strung up with stair rods. You need to get some strength into your fingers.

"When I was little, I was [miming] playing left-handed guitar with a tennis racquet and my older sister, Ruth, turned it round and made me play the tennis racquet the other way instead.

"But the thing that really clinched it was some unsuccessful violin lessons - although they were successful in that they got me playing the guitar right-handed. That can help you develop a style where you have a strong left hand. I find that I can get vibrato on three strings at once, that sort of stuff.”

Learning the language

The reputation he won as a guitar hero in the classic mould, during the Straits years, will be how some always think of him. But Knopfler says that he’s closer to the plain acoustic songcraft of his early days than ever.

“I think with me there’s two sides to it. Most of the time I just use the guitar as something to help the songwriting,” he explains.

"It’s a whole different thing being a musician from being a ‘guitar player’"

“It tends to be not particularly demanding. But every now and again if I’m sitting down and trying to learn something, moving it forward a little bit, you realise the depth of the thing - but that is more to do with being a musician.

“It’s a whole different thing being a musician from being a ‘guitar player’. I think if I’d had to make a living with the guitar as a guitar player, I think I’d have spent a lot more time trying to achieve a rounded position with it, where I could do more with it. But there was a spell back there - a long time ago now - where I realised I had to. I had to improve the vocabulary, just because of the kinds of things that I was doing.

“And when you go into more sophisticated chordal stuff, you’ve got to make yourself learn all that stuff. Just like you did when you were a teenager. And then you can start to put more complex constructions together, and in my case I just became used to the sound of those things.

"Almost like learning a language and starting to use longer words. So that a lot of their mystique and the impossibility of it, this foreign language... you start to slowly put it together a little better.”

Core values

The point Knopfler makes about the distinction between being a musician and a guitar player is an interesting one. In common-sense terms, to be a guitarist is, by default, to also be a musician.

"It’s always a joy to have great players around you. And they let me get away with murder!"

But on another level, what instrument someone chooses to play is not as important as the prime virtues of musicality that exist in all of us to a greater or lesser degree: being able to listen sensitively, to play only what’s appropriate, to sound notes that have a magical quality.

He’s generous with his praise for the musicians who contributed to Tracker, and says they all possess that high degree of musicality, including the extraordinary Canadian singer Ruth Moody with whom he duets on the album’s closing track, Wherever I Go.

“It’s always a joy to have great players around you,” he adds. “And they let me get away with murder. So if I make a mistake somewhere, the band will never comment on it. And I said that to Richard one time: I said, ‘I’m sorry about the greeny’ and he said, ‘The singer is always right!’ So they let me get away with it,” he concludes, with a smile.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.